Archival Art Will Not Save Us

Archival work has a place in historical recovery and cultural self-understanding. But not every artwork must be archival, and our politics shouldn’t end with presence rather than action.

Last fall, I attended a double documentary screening at Welcome to Chinatown of Christopher Radcliff’s 15-minute short, “We Were the Scenery” (2025), and Elizabeth Ai’s New Wave: Rebellion and Reinvention in the Vietnamese Diaspora (2024). The audience was packed, and with dinner provided by local downtown hotspots, it’s easy to see why.

Over the past two years, both documentaries have been running through the film circuits to much critical acclaim, with “We Were the Scenery” winning the Short Film Jury Prize in Nonfiction at Sundance and the Special Jury Prize for Documentary Short at the Los Angeles Asian Pacific Film Festival, as well as a recent Oscar nomination. Meanwhile, New Wave was an official selection of the Tribeca Film Festival in 2024 with a jury mention for Best New Documentary Director and of the Viet Film Fest, among others.

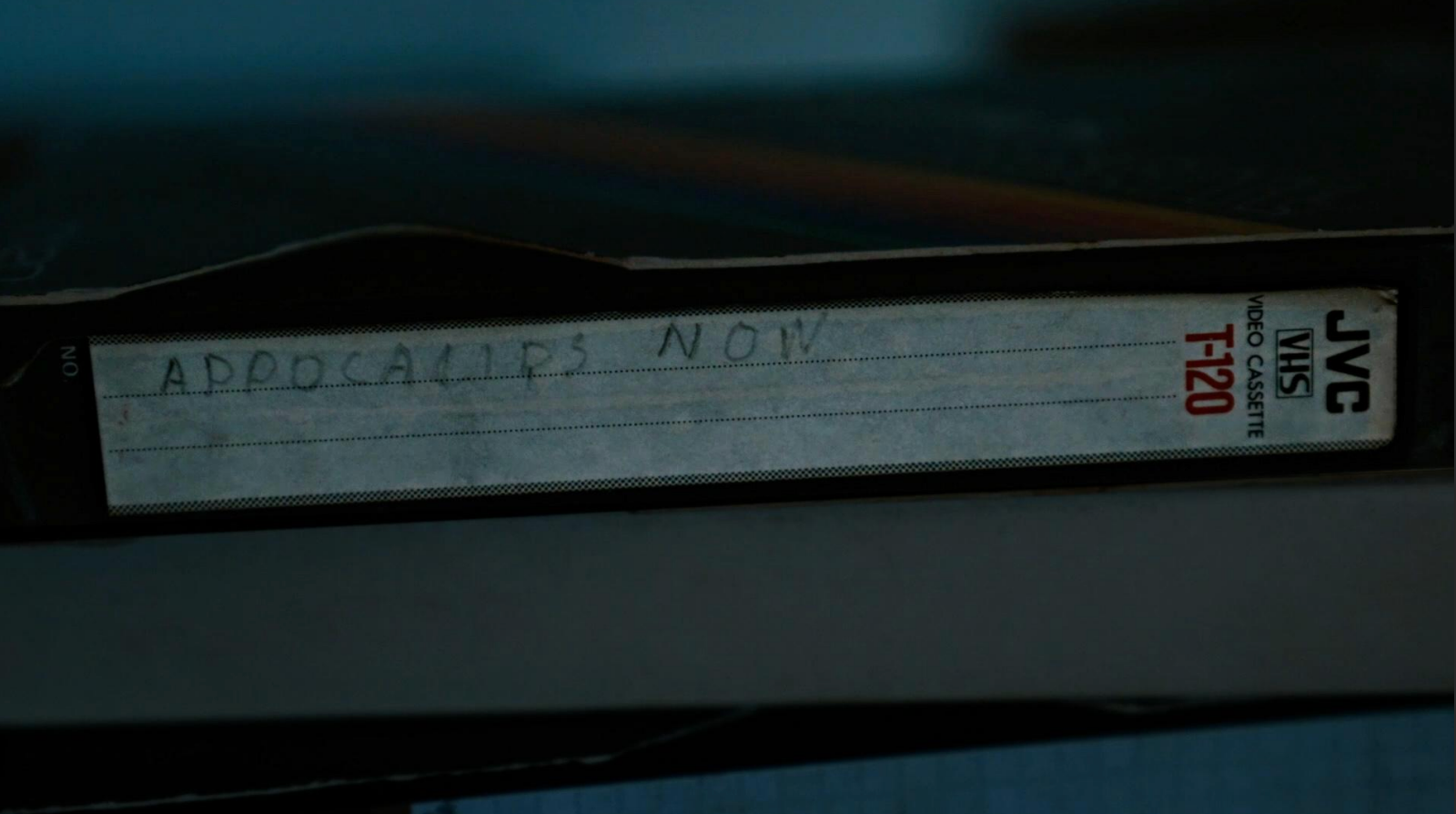

The accolades are well deserved, and both films are spectacular in their own ways. Radcliff’s focuses on the writer and National Book Award Finalist Cathy Linh Che’s parents, two Vietnam War refugees who were stranded in a camp in the Philippines and wound up being extras in Francis Ford Coppola’s 1979 Apocalypse Now. But rather than rehashing Joseph Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, which inspired Coppola, we instead reorient our attention to the memory of these two charming people, whose own wartime traumas were reduced to mere background, or “scenery.”

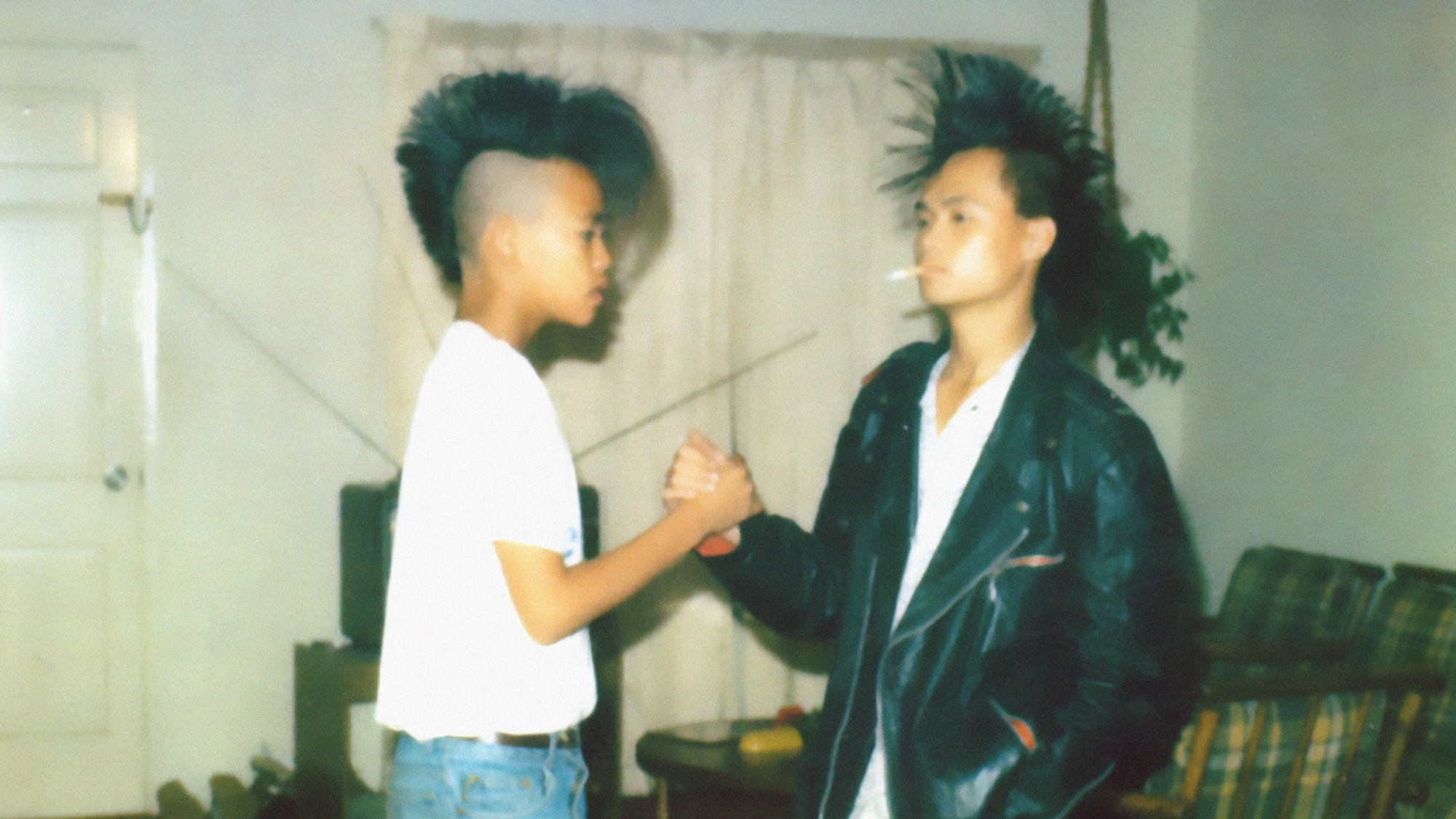

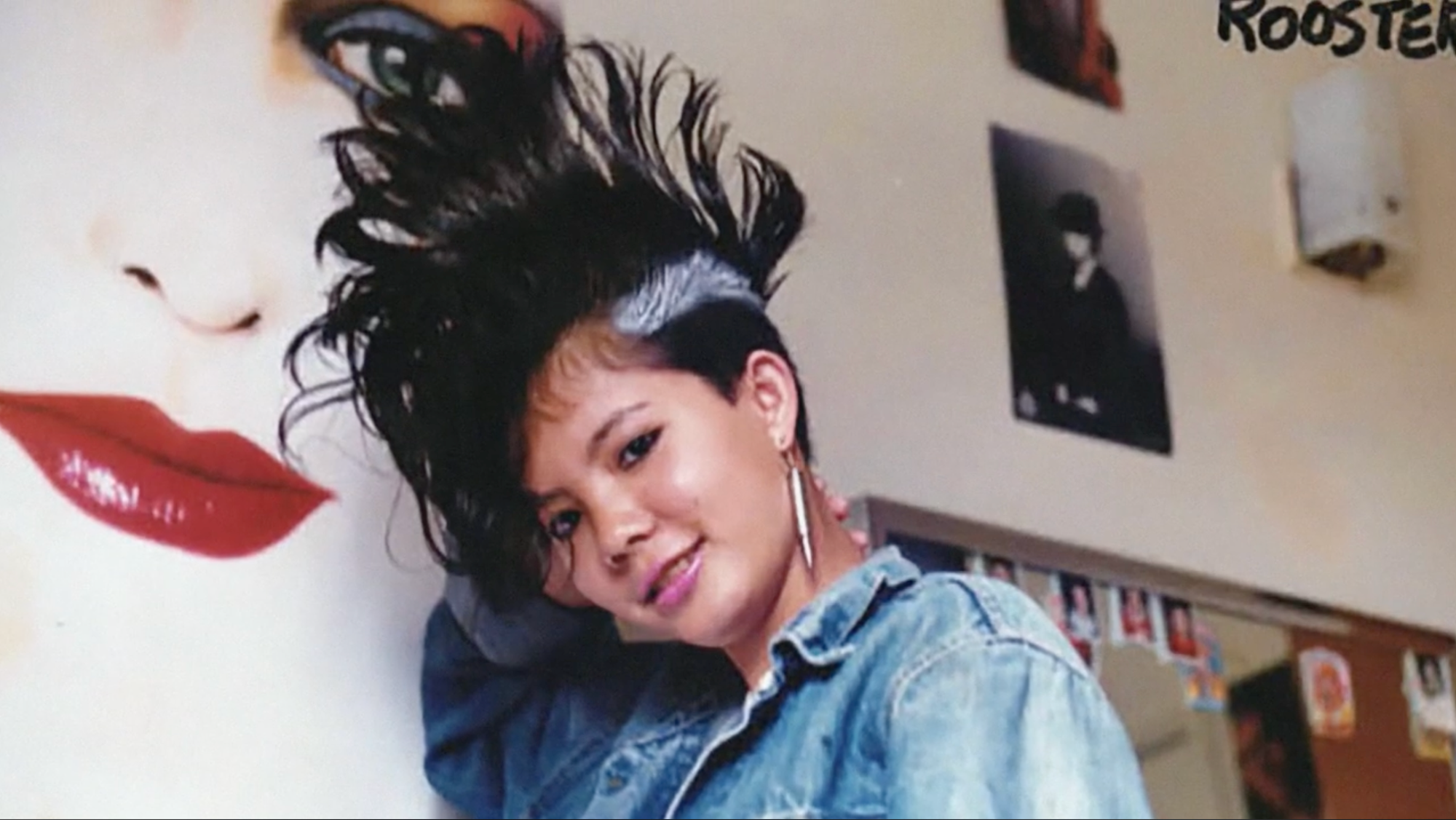

Meanwhile, Ai’s film focuses on the niche but impactful phenomenon of California’s Vietnamese New Wave, a popular version of Euro disco and synth pop in the 1980s and ’90s. Think big hair-sprayed creations, black leather jackets, and enough youthful punk-angst to get you through the Reagan and Bush Senior administrations. While the documentary centers on Ai’s own encounter with this vibrant subculture and her family’s fraught attempt to secure the American dream, the real star is Lynda Trang Đài (born Lê Quang Quý Trang Đài), the OG bad girl of Vietnamese-American music.

Both films are as auspicious as they are poignant. Vietnamese-American cultural production of late, especially in light of the 50th anniversary of the Fall of Saigon last year, generally prefers this confessional, documentarian mode of storytelling. It is a recuperative form of history-making, a splicing of grand narratives that aims to recenter the humans and, ergo, the humanity behind these larger-than-life cultural phenomena. Effectively, they are affirmations that marginalized communities, such as Vietnamese Americans, do indeed have our own subcultures and irreducible logic of memory and forgetting. They provide, as the Pulitzer Prize winner Viet Thanh Nguyen has characterized it, a kind of “narrative plenitude” to our stories of refugeeism, immigration, and continual pontification on the cracks and crevices of this fragile American life.

While the documentaries are successful and generative on their own, what raised my ire was the question-and-answer portion of the screening. As usual, there was discourse about “recentering” and “reframing,” and gestures toward engaging with childhood traumas and troubled family relationships from which we are all recovering. These concerns fit the tone of the documentaries, and jived well with the crowd in attendance.

I was disappointed, however, when the conversation fell into the predictable trope, or trap, of “archival practice.” Look back at any major art opening, fair, or even artist talk in the past few years and that term is sure to turn up. Archives are sexy, after all, and those who can spew its tenets and extricate its profundities are seen as practitioners of an invisible prophetic labor, or heralded as prophets of the limits and depths of our cultural horizons.

The simplest terms of this logic, as I perceive it, are as follows. First, as people of color, we’ve been deprived of a certain representational existence within Euro-American media. Second, as refugees specifically, we have produced our own visual and consumer culture and translated the things we wish we had into our own contexts. Third, half a century after the Vietnam War, we now have the means of production and the privilege of hindsight that allows us to work with greater intentionality rather than immediacy. Lastly, by producing such artifacts, not only are we adding to the conversation about community and belonging, but we are also relegating these objects or works of art into the cultural market for perpetuity and future reference. Voila, the putative archive.

Archival work has a place in historical recovery and cultural self-understanding. But is it true that we must produce for this ever-Hungry Hungry Hippo, or carry on with our cultural labor as though we’re tasked with crafting some pre-ordained and untouchable objet d’art? Is liberal consumption and dialectical self-affirmation the panacea for our historical woes? I’m unconvinced that cultural abundance and accumulation free us of pain or help us produce better art.

Personally, I am growing tired of archives, or rather of the over-romanticization of them as infinite sources of liberatory politics. To me, it is a failure of representational politics when our discourse ends with presence rather than action. After all, one of the defining features of socially conscious or politically effective contemporary art isn’t simply its capacity to insist on urgency in the here-and-now, but its willingness to host the sometimes unsavory yet necessary conversations that such urgency demands. For example, Titus Kaphar’s painting of a Black mother holding the empty silhouette of her child for the cover of Time during the height of the Black Lives Matter movement exemplifies this type of engagement, where representations of death and absence in red, white, and blue are themselves the demand for political reckoning and elicit critical social discourse concerning racism in America.

One successful example of this archive-as-practice for the Vietnamese diasporic canon is the exhibition Kho Tàng Nhạc Vàng held at Seattle’s ARTS at King Street Station gallery last summer. Organized by curator and independent filmmaker Thanh Tân, co-founder of the SEA Vinyl Society, the interactive show centered on pre-1975 South Vietnamese records and song sheets — one of the largest collections of its kind. Here, no rhetoric is necessary: The archive’s existence is its politics because these songs from the former Republic of Vietnam were systematically destroyed and remain legally banned under Vietnam’s current government.

Undoubtedly, New Wave and “We Were the Scenery” are exceptional examples that will serve to intervene within the counter-archives of the diaspora. But the conversations accompanying such remarkable works of art, as with artist talks everywhere, must also perform that generative labor rather than simply invoke a discursive shorthand to explain their own significance. Yes, they contribute to an archive, but then the more interesting question becomes: “So what?”

In her ruminations on archival memories and the destruction of Palestine for Dazed, Salma Mousa warns readers that “we must resist the urge to historicize our struggle before it’s over.” I believe this holds true for the Vietnamese diaspora. My point is this: We don’t need to have all the answers, and not everything needs to be an archive. But if our response to an environment of hyperconsumption is to produce ever more peace offerings to the chimeric archive of the future, then we risk losing the opportunity to deeply engage with the gaps of our own cultural moment. The kernels of art’s radical potential are foiled the second we fall back on that recursive reflex. And unless we contend with this knack for deferral, there will be no archive prodigious enough to tell us who we are.