Artists Stage Political Interventions in Video Games

“I’m interested in using games as a way to engage in and critique the fine art world, especially the economics of that world,” said Grayson Earle, an Integrated Media Arts adjunct professor at Hunter College and SUNY Baruch, and member of The Illuminator.

“I’m interested in using games as a way to engage in and critique the fine art world, especially the economics of that world,” said Grayson Earle, an Integrated Media Arts adjunct professor at Hunter College and SUNY Baruch, and member of The Illuminator. An image of Ai Weiwei’s famous triptych “Dropping a Han Dynasty Urn” (1995) flashed on a projected screen.

“This triptych of Ai Weiwei is supposed to be a dialogue about the role of destruction in art and culture. Weiwei’s breaking this 1,000-year-old urn as a subversive, creative person within China.”

Flashback to when artist Maximo Caminero recently dropped one of Ai’s vases at the Perez Art Museum.

“Ai Weiwei and his team said [Caminero] had no right to do this. To me, it was really strange to hear — China is making the exact same claim that Ai Weiwei had no right to break a Han Dynasty urn. And then there’s this similar intellectual regime of Ai Weiwei’s art career telling this guy that he had no right to break his work.”

Earle spoke to a classroom-sized audience at Different Games, a conference on diversity and inclusivity in video games that happened in early April, at New York University’s Polytechnic School of Engineering campus in downtown Brooklyn. The conference drew mostly young game designers who came to hear about how games might cross into other cultural activities and included panels on political topics like the one Earle was a part of, “Games as Art, Activism, and Representations of the Real.”

So what was Earle’s response to the vase dropping? He developed the online game “Ai Weiwei Whoops!” where users can drop as many Ai Weiwei pots as they want.

“Ai Weiwei Whoops!” is one way of thinking about games as political commentary. The game, according to Earle, is meant to ignite a debate about the value of fine art and the role of destruction when you think of it in terms of digital reproduction online. He’s tried to elicit a response from Weiwei through Twitter about his ideas, but has yet to receive a response.

Earle’s other work includes illegally advertising “Koch=Climate Chaos” on the facade of the Metropolitan Museum of Art and projecting playable games on private buildings, such as “Tax Evaders,” in which anyone with the designated Wii-mote can virtually fight corporate tax dodgers and return the stolen tax money to public institutions.

Another panelist, Kimberly McLeod, a PhD candidate in Theatre and Performance Studies at York University whose dissertation focuses on how performances in new media can assist political engagement, screened performance pieces “dead-in-iraq” (2006–2011) by Joseph DeLappe and Eva and Franco Mattes’s “Freedom” (2010).

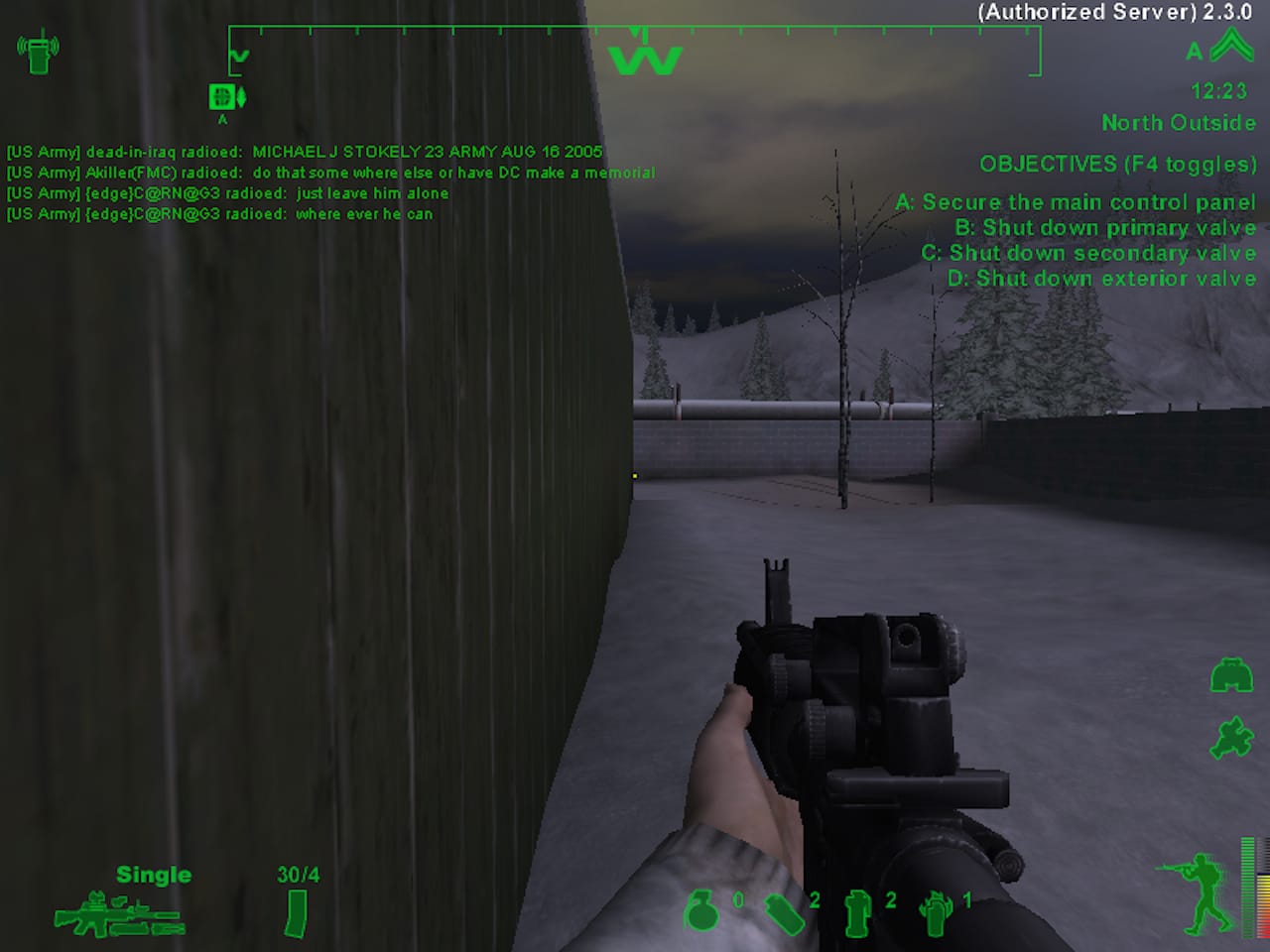

“Freedom” uses the virtual space of popular first-person shooter game “Counter-Strike” to stage a performance piece: instead of following the game’s narrative and shooting as many other players as possible, Eva Mattes implores other players not to kill her. As she types and explains she is a performance artist making art in the space of the game, she is shot and killed, only to respawn and have the whole exchange occur again. DeLappe’s “dead-in-iraq” is similar in that he also uses a virtual space, that of video game “America’s Army,” to stage a game-based performance intervention: in using the “America’s Army” texting system, he types the name, age, service branch, and death of every man and woman killed in Iraq.

“These interventions destabilize assumed relations between gamers and frequently provoke very violent reactions,” said McLeod. “While these are both ephemeral interventions and that rely on real-time engagements of the artists in the gaming space, the fleeting but pointed performances have tactical agency. DeLappe and Mattes come from outside of any in-group within these games spaces and they resist the rules put in place by corporate and military game spaces.”

Essentially, gamers that regularly use these games are made to feel out of place and uncomfortable with their actions when confronted by these outsiders who disrupt their space.

As of late, video games might be the medium du jour for the art world: museums have used them as a bid to attract younger gamers to view art; they’ve also curated full exhibits dedicated to indie games and in-game art. Small galleries across the country have been commissioning young illustrators to create video game-inspired work for curated shows.

When asked how these games-as-critiques or how the political art in video games becomes subverted within the art museum context, McLeod and Earle didn’t have a clear answer — only that it’s a developing issue.

“Both of these pieces have been screened in galleries and available online and it creates an interesting question about who are they making this for,” said McLeod in reference to DeLappe and Mattes’s works. “Is it really for us to watch and judge these gamers in a heavily edited video after they react? The Mattes have become very famous for these art pranks, they critique that kind of system, but then they’ve also created their own artwork to use within that system as well. It’s problematic.”

Earle agreed, and implied that perhaps the video games industry is something the art world wants to possess more of, perhaps for financial reasons, and perhaps just for bragging rights.

“I see a lot of problems with the way that games get integrated within museums,” said Earle. “At MoMA, there was that huge video game exhibit, and 40 percent of the games were broken, they weren’t working. The fine art world is trying to take ownership of this new arts practice and game-based creativity. It wasn’t born within the fine arts community but now they’re saying, ‘Oh no, this is ours now because we’re the art world.’ There’s a conflict there, and I’d like to see a bit more of a push from the other side.”

Different Games took place at New York University’s Polytechnic School of Engineering (2 Metrotech Center, 8th Floor, Downtown Brooklyn) on April 3.