Edward Zutrau Was a Chromatic Rebel

He combined the reductive strain of Abstract Expressionism with the principles and style of Japanese ink painting, for something uniquely his own.

Every now and then a press release for an artist unfamiliar to you catches your attention for the right reason. It is seldom the description, which I tend to distrust, that piques my interest, but rather the biographical context. This was the case with the exhibition Edward Zutrau: Thirty Years, Two Worlds at Lincoln Glenn. Born and bred in Brooklyn, Zutrau studied with the painter Will Barnet, and was briefly inspired by his mentor’s abstract “Indian Space” period. In 1955, Zutrau, then in his early 30s, married a woman from Japan, where the couple moved soon after. During his time in the country, he exhibited his work there, but not in the United States.

He returned to New York in 1967 and had three solo shows with Betty Parsons between 1972 and ’80. Though Parsons became a close friend, he seems to have received little attention for his art. Calvin Tomkins mentions him only in passing in a 1975 New Yorker article on Parsons, and he is not on Wikipedia. Zutrau finally gained some attention just a few years ago. For the most part, reviews of his work noted his indebtedness to first-generation Abstract Expressionists Mark Rothko and Clyfford Still, and (if you believe Clement Greenberg) their only heirs, the Color Field artists.

It can be far easier to see similarity than to discern difference, but since none of these reviews jibed with the images I saw online, I had to see the art for myself. Of the 12 paintings on view, all in oil on linen or canvas and dating from 1956 to 1984, seven were made while he lived in Japan. Though the majority are small, four mid-sized and large paintings form the heart of the show.

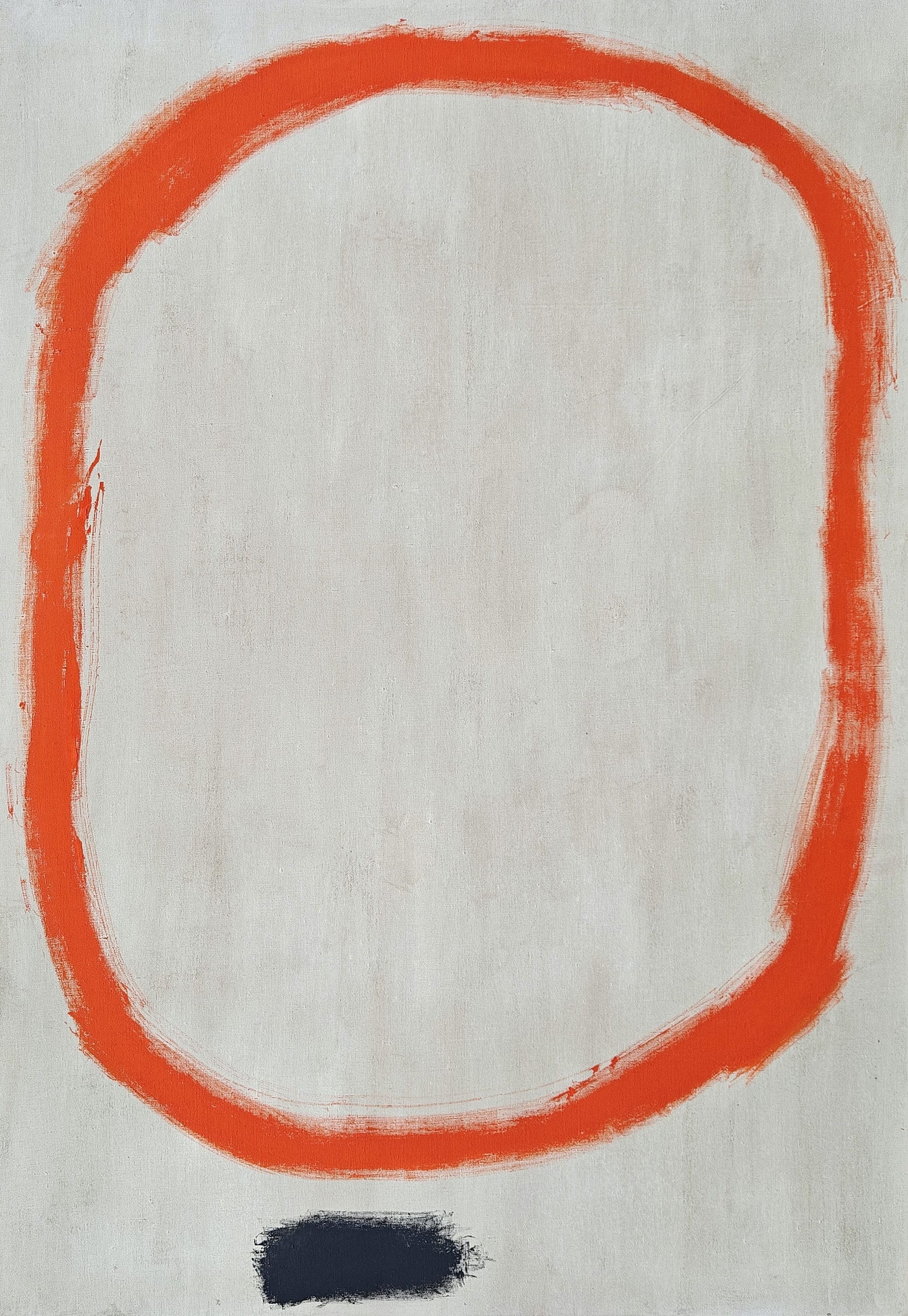

Zutrau absorbed the reductive strain of Abstract Expressionism, but by combining it with the principles and style of Japanese ink painting, in which each mark is permanent, he forged something uniquely his own. This was clear to me from the moment I saw “Untitled” (1969), displayed in the window facing the street. As I stood and looked at it on a drizzly gray day, I forgot that it was raining.

In contrast to other artists who are associated with the second generation of Abstract Expressionists — including those who used a loaded brush and those who broke free by pouring paint or suppressed any sign of the hand — Zutrau took a cue from ink painting, or what has come to be known as “first thought, best thought.” He trusted that initial instinct without stepping back and commenting on it.

“Untitled” is comprised of two marks. A loosely drawn, reddish-orange oval, painted with a dry brush, takes up most of the vertical, light gray canvas. One can see where Zutrau added more paint to his brush and continued drawing the line, which slowly encircles the painting’s surface with a seismographic sensitivity that registers the hand’s determination and vulnerability. Beneath this open shape, near the painting’s bottom edge, is a short, black stroke, almost like a painted em-dash. Despite the difference in size, the two shapes feel equal. They are separate but entangled, and together become an asemic ideogram that nudges us to reflect upon the relationship of abstract sign and ideogram, meaninglessness and meaning.

What distinguishes Zutrau’s ideogrammatic sign from Japanese calligraphic painting is the wavering slowness of the painted line and his use of two colors, one for each mark. Confidence is conveyed by the solid, even black line that radiates mastery. Zutrau began exploring this incommensurate unity by using a dry brush, juxtaposing closely related hues or complimentary colors, and offsetting them by introducing an unconnected color. By interrupting or skewing chromatic sequences, he pulls us closer, and invites further scrutiny.

In two paintings titled “Kamakura” and another untitled work, all three dated 1963, Zutrau disrupts visual logic in two distinct ways. The “Kamakura” paintings are composed of two large vertical rectangles set side by side within a horizontal canvas, not quite touching each other or the painting’s edges. In one, he upsets the balance of complementary cerulean blue and dark magenta with a narrow black shard on the left side, pushing its way into the picture plane. For the other, the balance of the two dark gray rectangles taking up the space is disrupted by an orange sliver on the far right. Colors neither bleed into each other nor collide in his works.

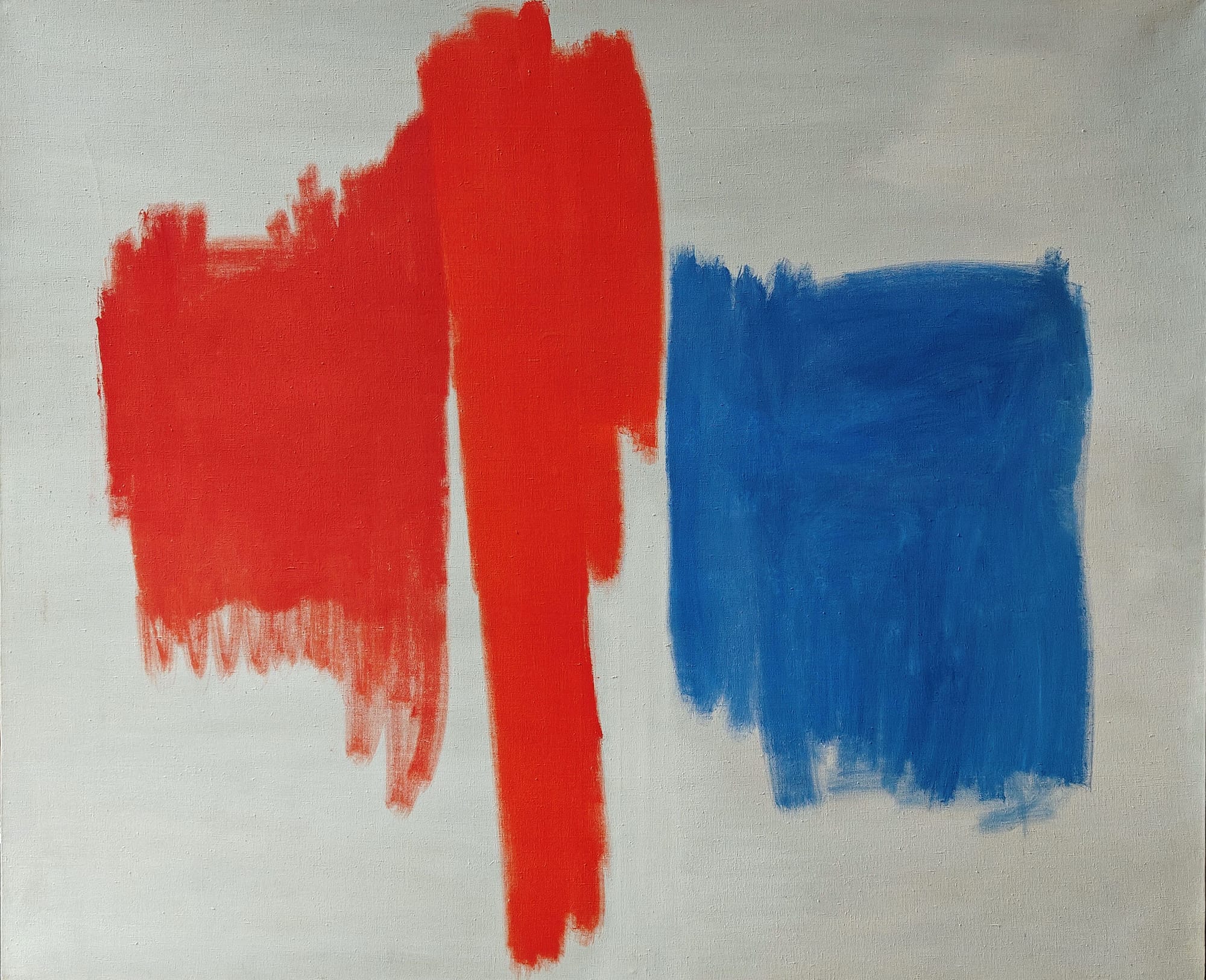

In the untitled work, two rough, feathery-edged rectangles, red and blue, float on the horizontal white ground. Between them, separating these complementary colors, is a ragged brighter red form that spans the height of the canvas. Balance and disruptions overlap, resulting in something new and unexpected.

Made after he returned to the United States, Zutrau’s “Untitled” (1971) suggests connections to Rothko and to the younger Robert Ryman at first. Yet look longer at the thinly painted, soft-edged yellow form that fills the pictorial space, but doesn’t touch the edges, and these associations fall away.

Through living in two different worlds and experiencing their art, Zutrau created a body of paintings that drew from both to become recognizably his.

Edward Zutrau: Thirty Years, Two Worlds continues at Lincoln Glenn (542 West 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through February 21. The exhibition was organized by the gallery.