From Chocolate Gramophones to MP3s: The History of Sound in Images

The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles by Terry Burrows is an illustrated history of recorded sound, from gramophones to the rise of digital.

In 1902, the Stollwerck confectionary company of Germany released a gramophone that played tiny chocolate discs. After listening to their tunes, users could eat the music. It was a short-lived novelty, and one of the more whimsical experiments in the sound recording and playback history chronicled in The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles.

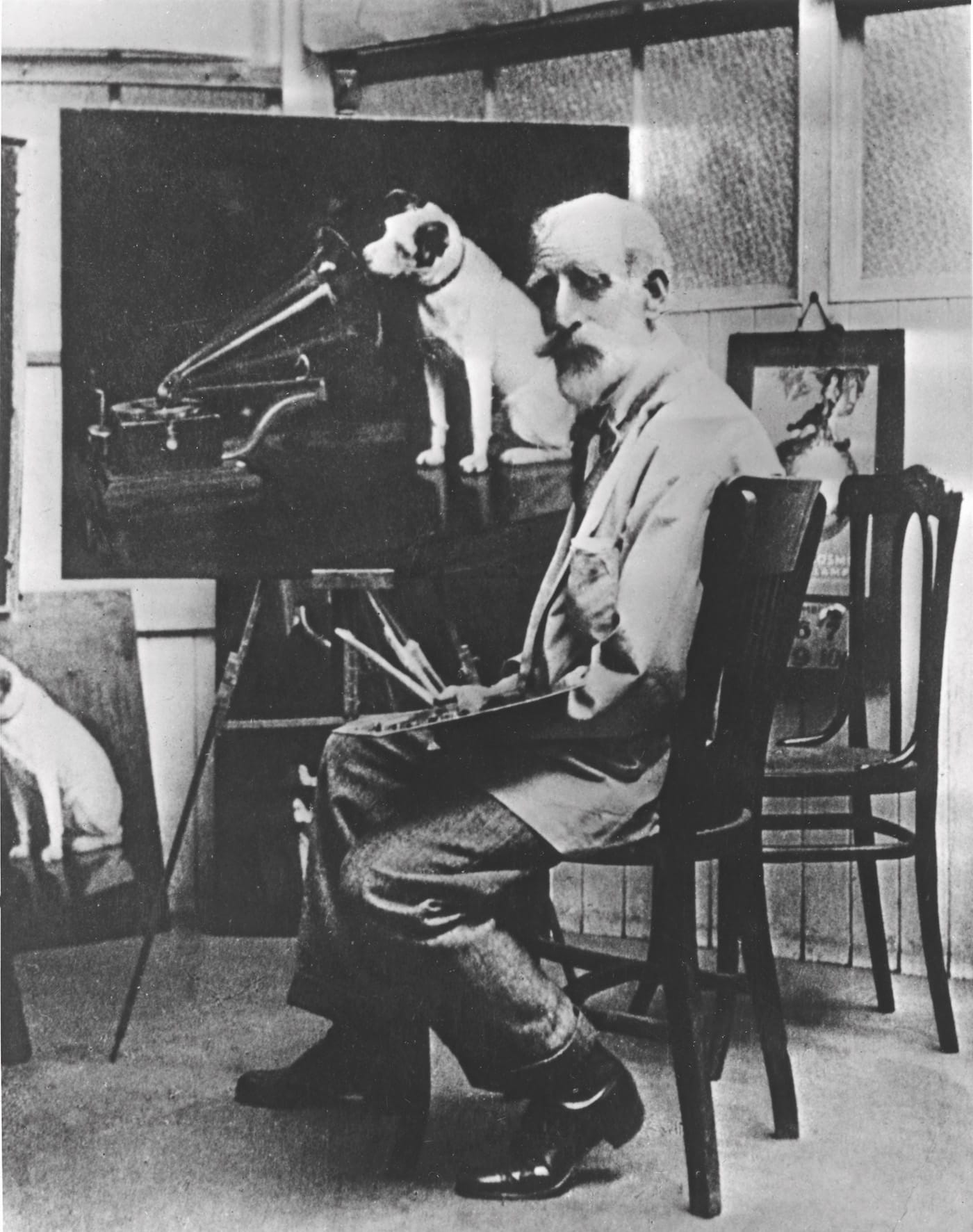

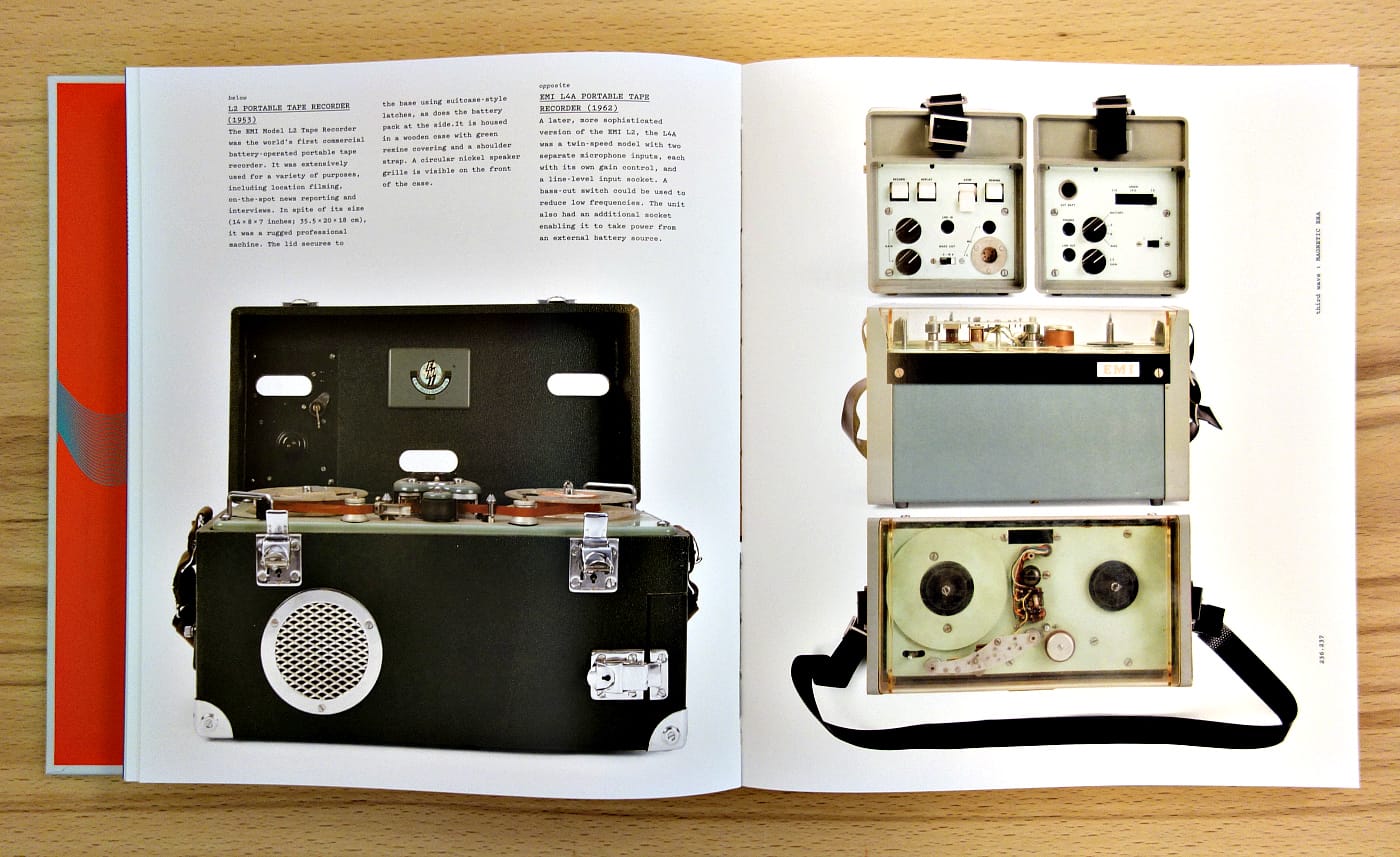

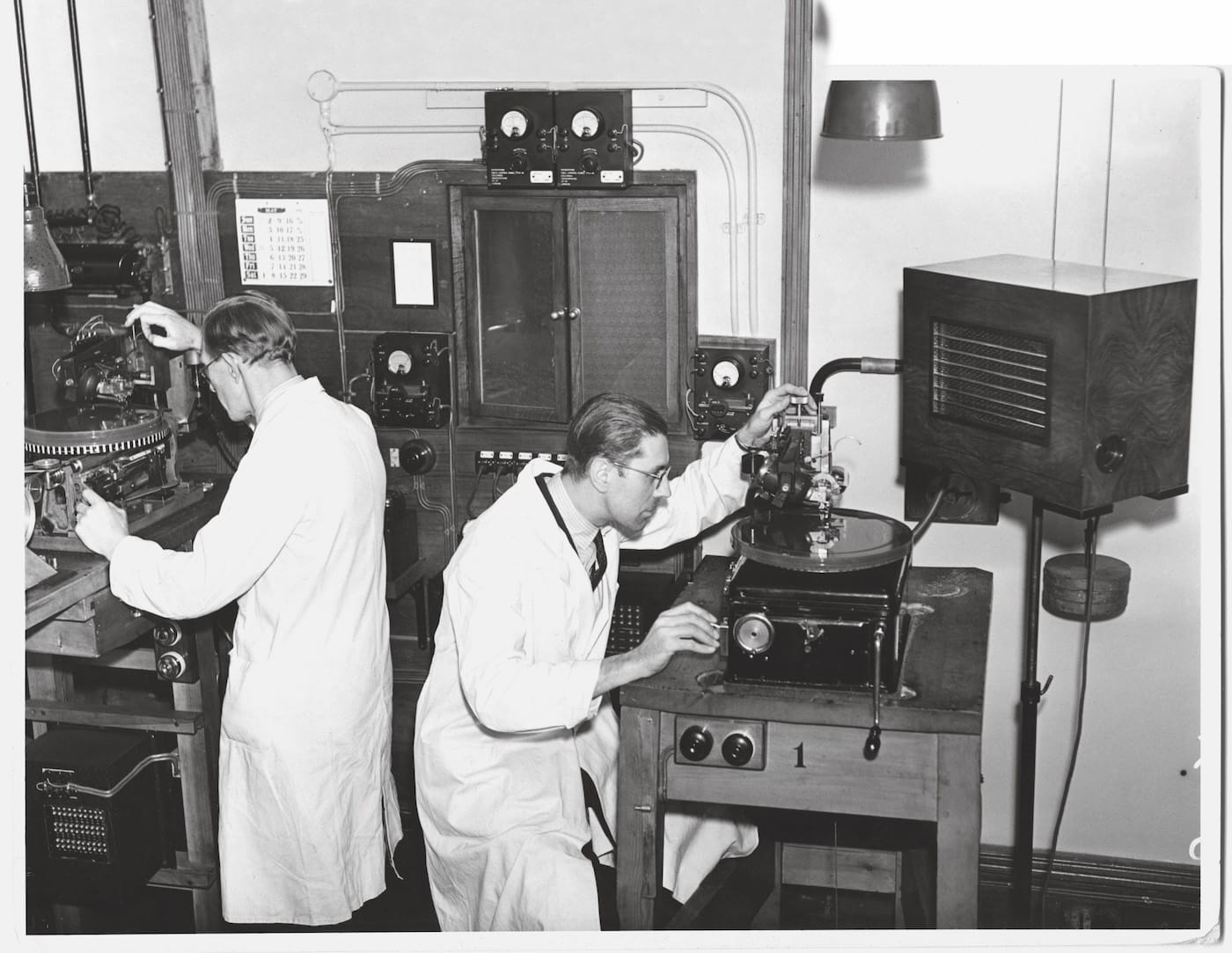

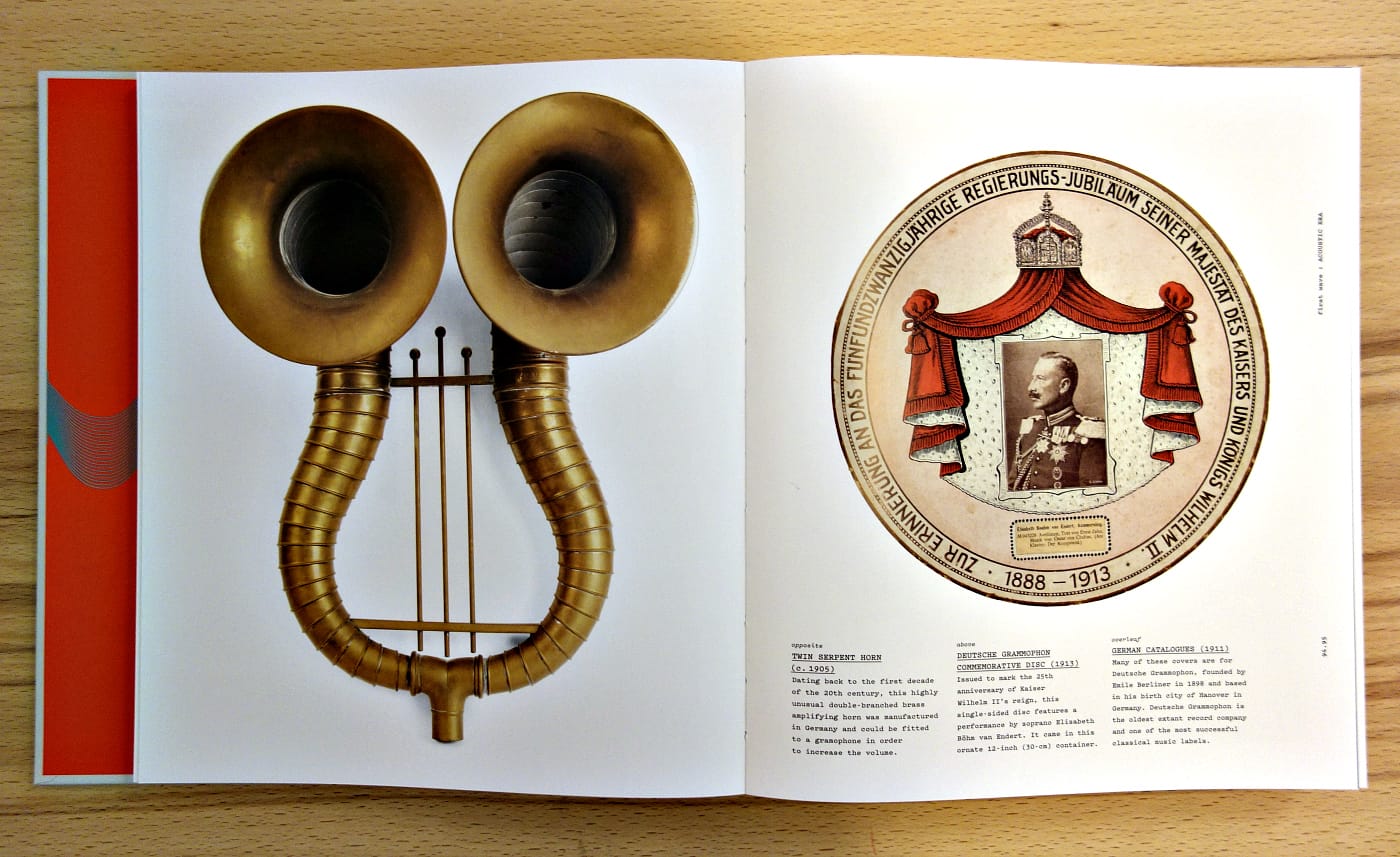

The book by Terry Burrows, a music author and musician known by his alias, Yukio Yung, was recently released by Thames & Hudson. It’s a publication designed with appealing details for the titular audiophiles, from blue pages illustrated with patent illustrations dividing the four chronological sections, to high-quality photographs of objects from at EMI Archive Trust. They include archival material and some incredible rarities, like a 1905 luxury Monarch gramophone made of oak, which was given to Captain Robert Falcon Scott by the Gramophone Company and taken on the ill-fated Terra Nova Expedition on which every party member died. When the gramophone was later recovered from one of the expedition’s icy camps, it was still in working order.

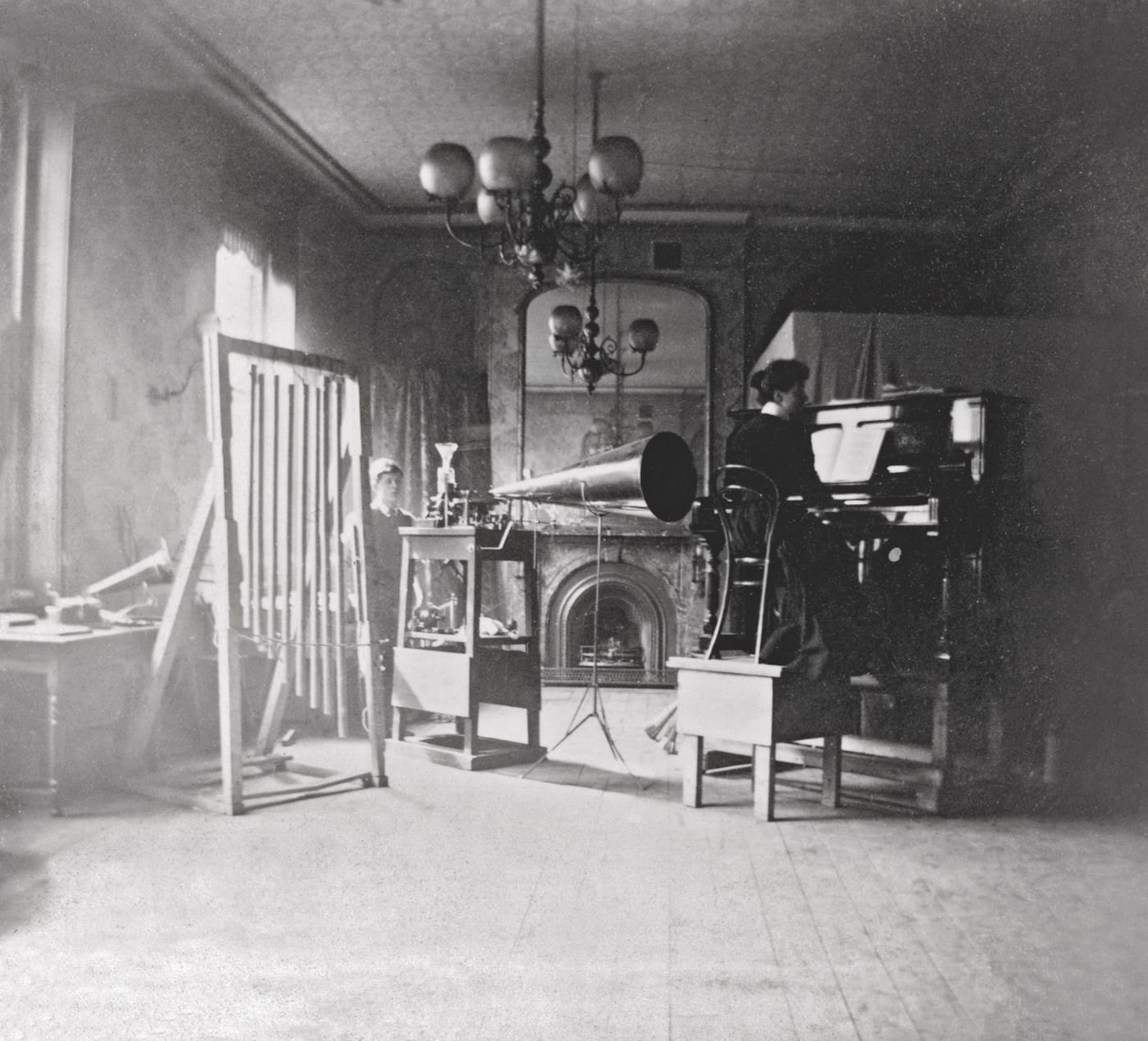

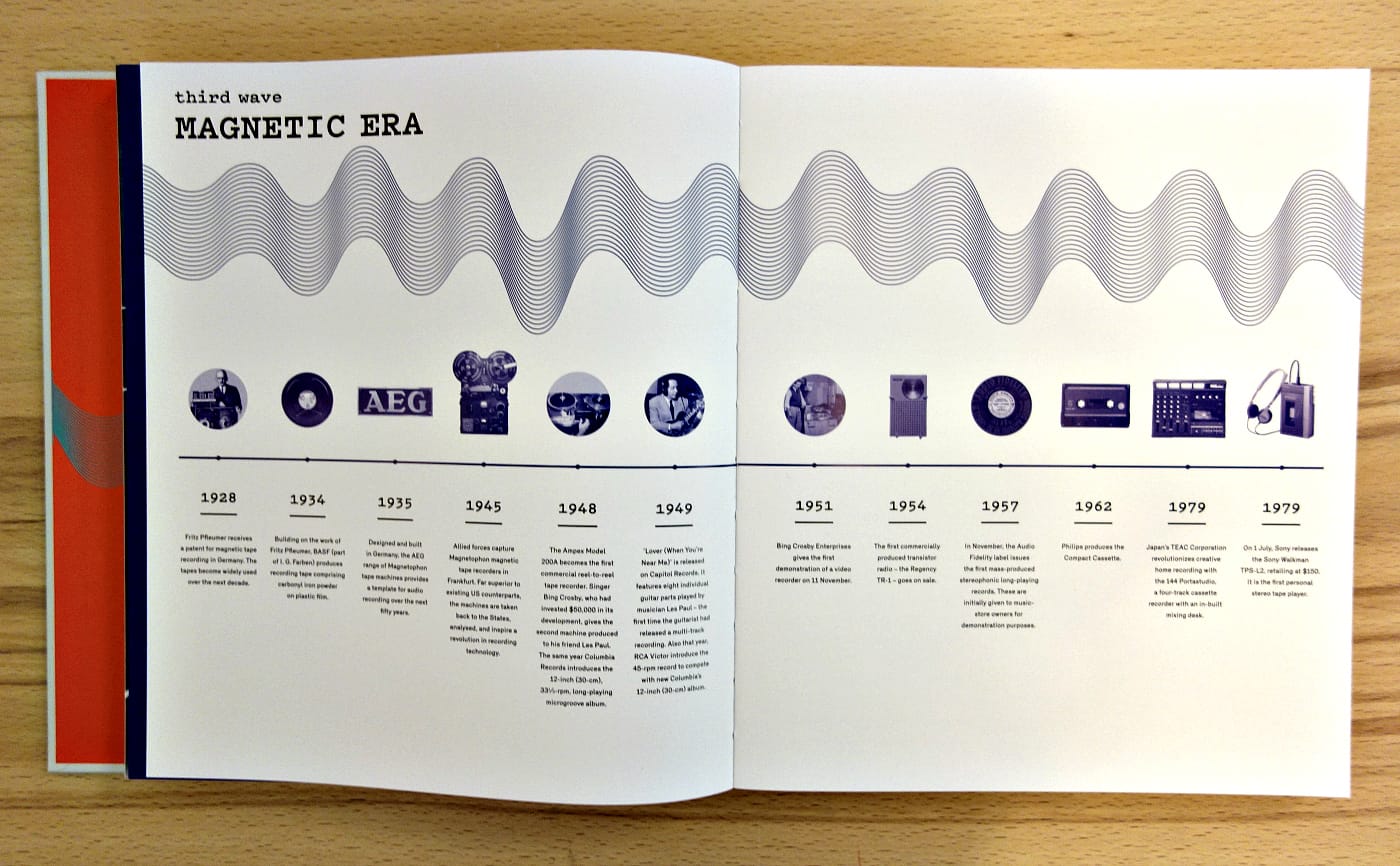

The Art of Sound is straightforward in its timeline of text and visuals, beginning in 1857 with Édouard-Léon Scott de Martinville’s phonautograph, the first device for recording sound, and continuing to 2015, when streamed music outpaced online audio downloads. Music technology aficionados may already be familiar with much of this history, which covers the rise of the magnetic era as well as its decline with the emergence of the compact disc, and the book seems more aimed at people who are interested in music, but perhaps don’t know about all the engineering and design history behind it. Short biographies highlight well-known figures like Thomas Edison, who invented the phonograph, as well as more unsung innovators, such as Alan Blumlein, who developed stereophonic sound and was killed at the age of 38 during a World War II airborne radar system test.

On the topic of our current listening habits Burrows notes that, “As with many other aspects of modern life, the way in which we consume music has been metamorphosed by the internet.” Vinyl still has its adherents; rarer are the listeners who appreciate the textural character of wax cylinders or the stereophonic gramophone. That hardware history is central to The Art of Sound, where each progression, from acoustic, to electrical, to magnetic, to digital, altered the way we physically relate to music.

EMI, which holds many of the artifacts in the book, was formed when the Gramophone Company and the Columbia Phonograph Company merged in 1931. If you’re hungry for more old-timey audio images, the EMI Archive Trust has a Flickr gallery of photographs from the early years of the Gramophone Company; other resources related to their collections are on their site.

The Art of Sound: A Visual History for Audiophiles by Terry Burrows is out now from Thames & Hudson.