How Joan Miró and America Fell in Love

“In the future world, America, with its energy and vitality, must play a leading role,” he told Matisse.

BARCELONA — Six months before his momentous first trip to the United States, Joan Miró sent a letter to his New York City gallerist, Pierre Matisse. Writing from repressive Francoist Spain in the austere aftermath of the Second World War, the Catalan artist was searching for new frontiers. “In the future world, America, with its energy and vitality, must play a leading role,” he told Matisse.” I have to be in New York to be in direct, personal contact with your country; my work will benefit from that shock.”

That idea is at the center of Miró and the United States at the Fundació Joan Miró. While a 1982 exhibition highlighted Miró’s sizable influence on American artists, this one asserts that the US was actually a place of intense creative exchange. Accordingly, Miró’s work is presented alongside that of 48 US-based artists he met, collaborated with, or otherwise impacted during his seven visits to the country between 1947 and 1968. With nearly 140 artworks, the exhibition explores Miró’s entire US trajectory, from his debut in the 1920s to his later public commissions in Chicago, Houston, and other major cities. Just as his letter to Matisse confirms that he saw the US as a place that would change him profoundly, the show — which recreates a pivotal moment in 20th-century American art — uncovers surprising connections between the Catalan artist and his American peers.

Miró and the United States opens with the two artworks that initially introduced him to US audiences, in a 1926 Brooklyn Museum presentation, finally reunited again. The next gallery — dedicated to Miró’s lifelong friendships with architect Josep Lluís Sert and artist Alexander Calder — brings his “Mural Painting, 20 March 1961” (1961) to Europe for the first time since Sert donated it to the Harvard Art Museums. An important layer to the show is the building’s own Sert-designed architecture (he also designed Miró’s Mallorca studio). A Catalan in exile, he was the Dean of the Harvard Graduate School of Design and a significant force behind Miró’s American projects.

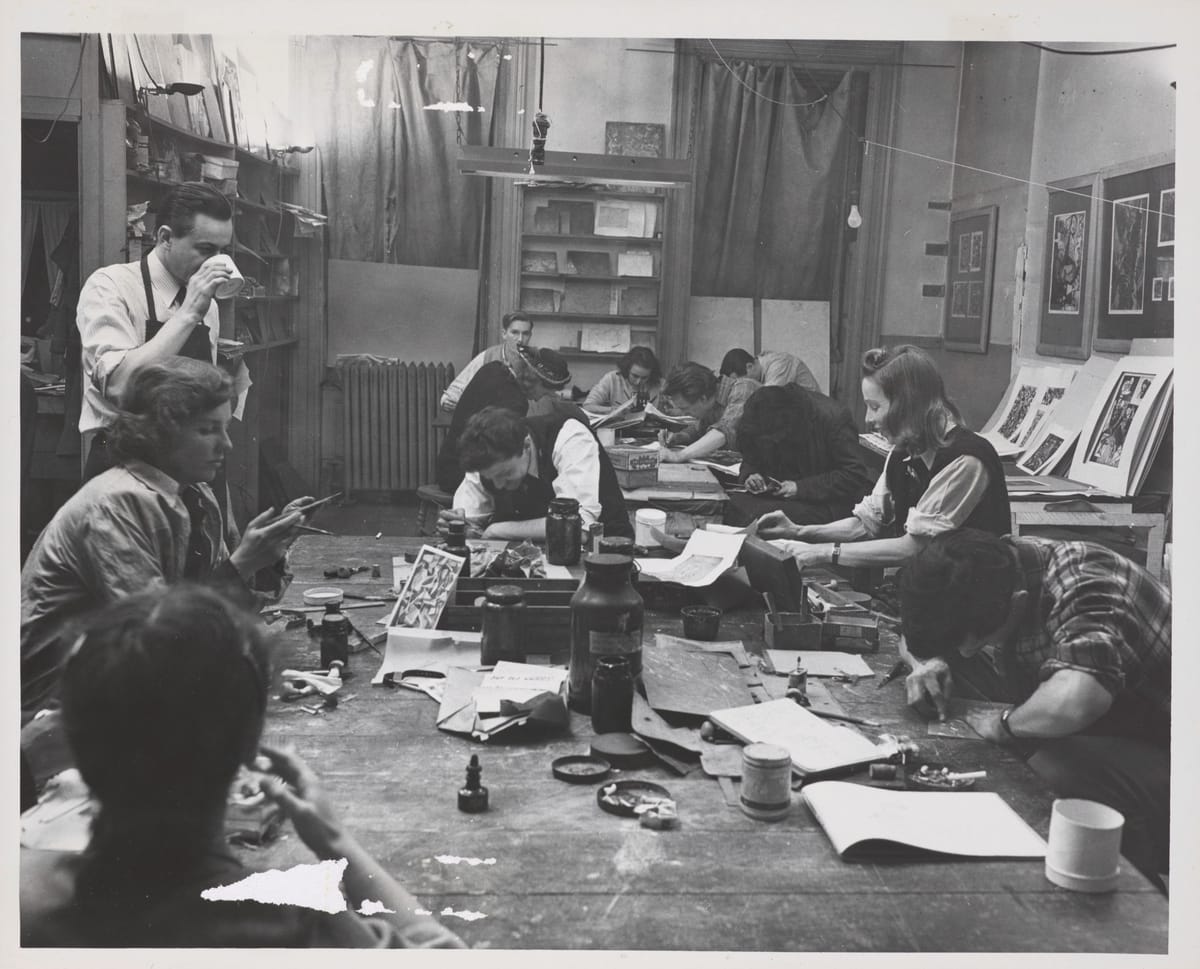

The US had long been the biggest market for Miró’s paintings, and American critics, curators, and artists embraced his work enthusiastically — he had already been the subject of surveys at major institutions including the Museum of Modern Art and San Francisco Museum of Art, and figures like Barnett Newman, Clement Greenberg, and Jackson Pollock said they revered him. One of the exhibition’s more illuminating aspects is its extensive documentation of Miró’s lesser-known art activities in the country. An especially exciting discovery is Atelier 17, a dynamic community printmaking space in New York City where Miró worked alongside Louise Bourgeois, Alice Trumbull Mason, and other prominent modernists. Filmmaker Thomas Bouchard’s documentary of Miró’s experimental print activity is on view, along with the plate and print he produced, plus prints by his fellow artists from the shop. Moments like this illustrate how Miró stretched himself artistically with the help of his American networks.

Another highlight is the curators’ focus on women artists. Often overlooked in their own day, the show literally centers their work in a women-forward installation strategy that threads throughout the show. For example, Lee Krasner’s stunning painting “The Seasons” (1957) receives pride of place in the main gallery space while smaller pieces by Robert Motherwell and Franz Kline hang on side walls. The curators also include lesser-known figures such as Sarah Grilo and Janet Sobel, as well as women artists who worked under masculine names like Michael (Corinne) West and Peter Miller (Henrietta Myers). All works are accompanied by biographies in Catalan, Spanish, English, and French.

The US influence didn’t end when Miró returned home. He subscribed to Life, Arts, and Art News magazines in order to “see what is happening in America,” as he once said (quoted in the catalog). Artworks in the exhibition dialogue with each other materially and technically, conveying that Miró was in conversation with his American peers and brought those influences into his later works. American jazz had a lasting impact, too, and the artist even inspired a 1961 album by the Dave Brubeck Quartet, which is featured in the show’s extensive documentation portion.

Later in life, Miró said, “It was really American painting that inspired me.” Miró and the United States shows how his connection to the US opened professional and creative territory that forever changed his life and work.

Miró and the United States continues at at the Fundación Joan Miró (Parc de Montjuïc, s/n, Sants-Montjuïc, Barcelona, Spain) through February 22. The exhibition was curated by Marko Daniel, Matthew Gale, and Dolors Rodríguez Roig in partnership with Elsa Smithgall from The Phillips Collection.

It will be on view at the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, from March 21 through July 5.