How Richard Wright Shaped John Wilson’s Protest Art

Wilson, like Wright before him, wrestled with the psychic toll of racial violence on Black families in his paintings and lithographs.

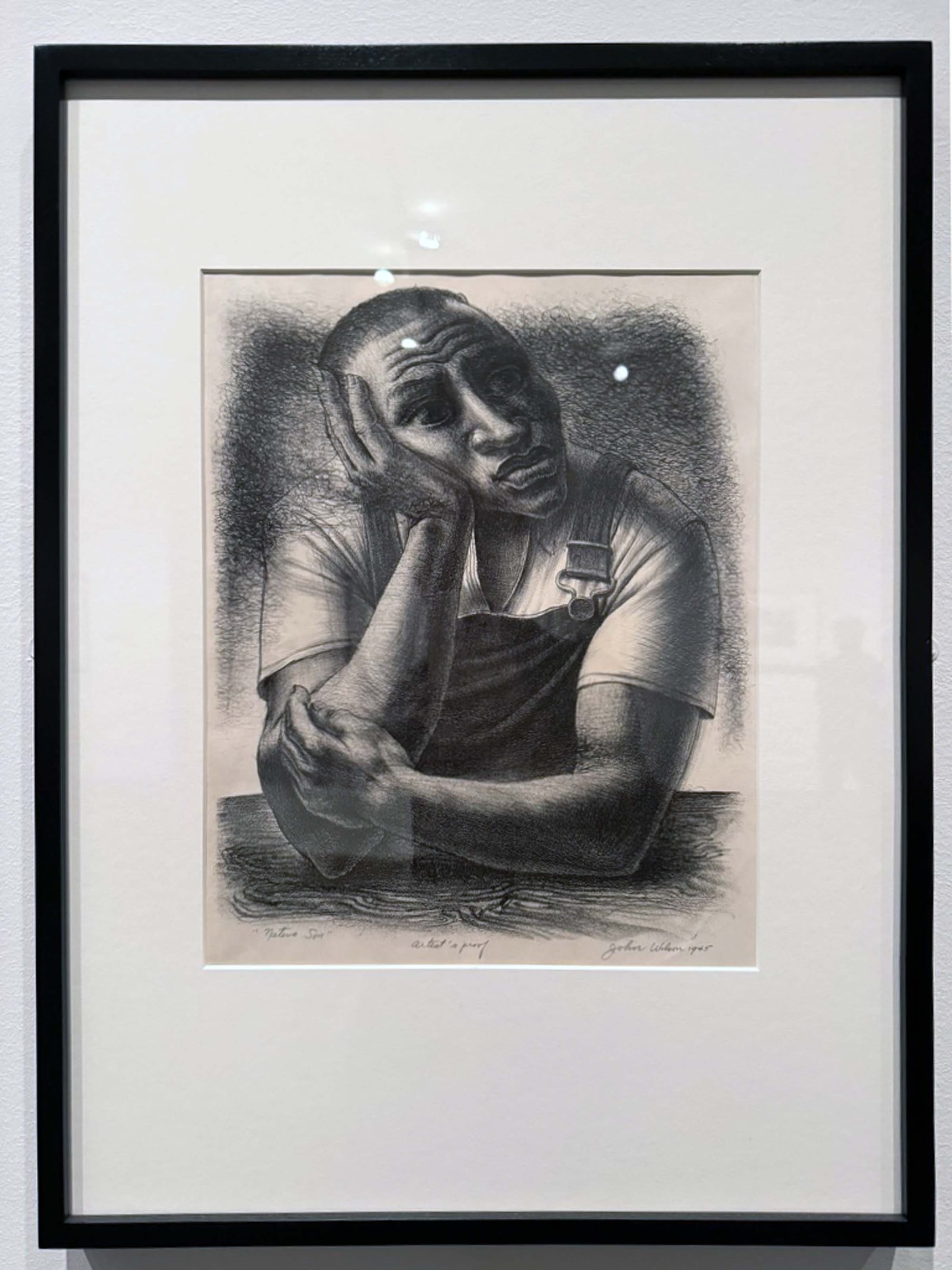

With 1940’s explosive Native Son, the novelist Richard Wright lit a fire in American literature, the embers of which still glow today. One of the most influential writers of the 20th century, he inspired many, including a young John Wilson, born in 1922 to Guyanese immigrants in the working-class neighborhood of Roxbury, Massachusetts. Wright, who established himself in the literary world in the decade before Wilson emerged in art, profoundly impacted the modern artist — his words appear in the political prints and paintings Wilson would go on to make. In Witnessing Humanity: The Art of John Wilson, on view at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, several artworks are inspired by or named after Wright’s books, like the lithographs “Black Boy” (1965) and “Native Son” (1942).

Witnessing Humanity reveals Wilson as a passionate reader, creatively invigorated by Wright’s protest fiction and inspired to charge his art with political purpose. Walk through the retrospective, and you’ll see Wilson, like Wright before him, wrestling with the psychic toll of racial violence on Black families in his paintings and lithographs. In A Contribution to the Critique of Political Economy (1859), Karl Marx wrote: “It is not the consciousness of men that determines their being, but on the contrary, their social being that determines their consciousness.” Wright’s protagonists and Wilson’s subjects embody Marx’s insight in their depictions of rural and working-class men struggling to maintain their dignity in a world designed to dominate them economically and socially. Both artists shared a worldview that the violence they witnessed and heard stories about growing up wasn’t just about terror — it was a tool to control and exploit Black labor.

Marxist and socialist ideas proliferated in their respective works, though Wright wrote about his eventual disillusionment with the Communist Party in the 1944 essay “I Tried to Be a Communist.” In Chicago, he met Southern-born Black Communists whose biographies would be woven into his first book, Uncle Tom’s Children, a collection of four novellas published in 1938. Each story verges on a polemical study, telling a tale of resistance to racial terror and depicting protagonists upholding their dignity in spite of their oppression — a unifying theme of Wilson’s work as well.

Wilson attributed the inspiration for one of his most acclaimed pieces, “The Incident” (1952), to Uncle Tom’s Children. In the dynamic mural, one man, shielding his wife and child, looks out the window in righteous disgust, shotgun in hand, as another is violently lynched by four members of the Klan, echoing the protective crouch one family takes on in Wright’s short story “Big Boy Leaves Home” (1938). Highlighted next to a study of the mural at the Metropolitan Museum is a quote by Wilson praising the story collection: “He put into words what I wanted to express visually, the struggle of African Americans to maintain their human dignity in an oppressive world.”

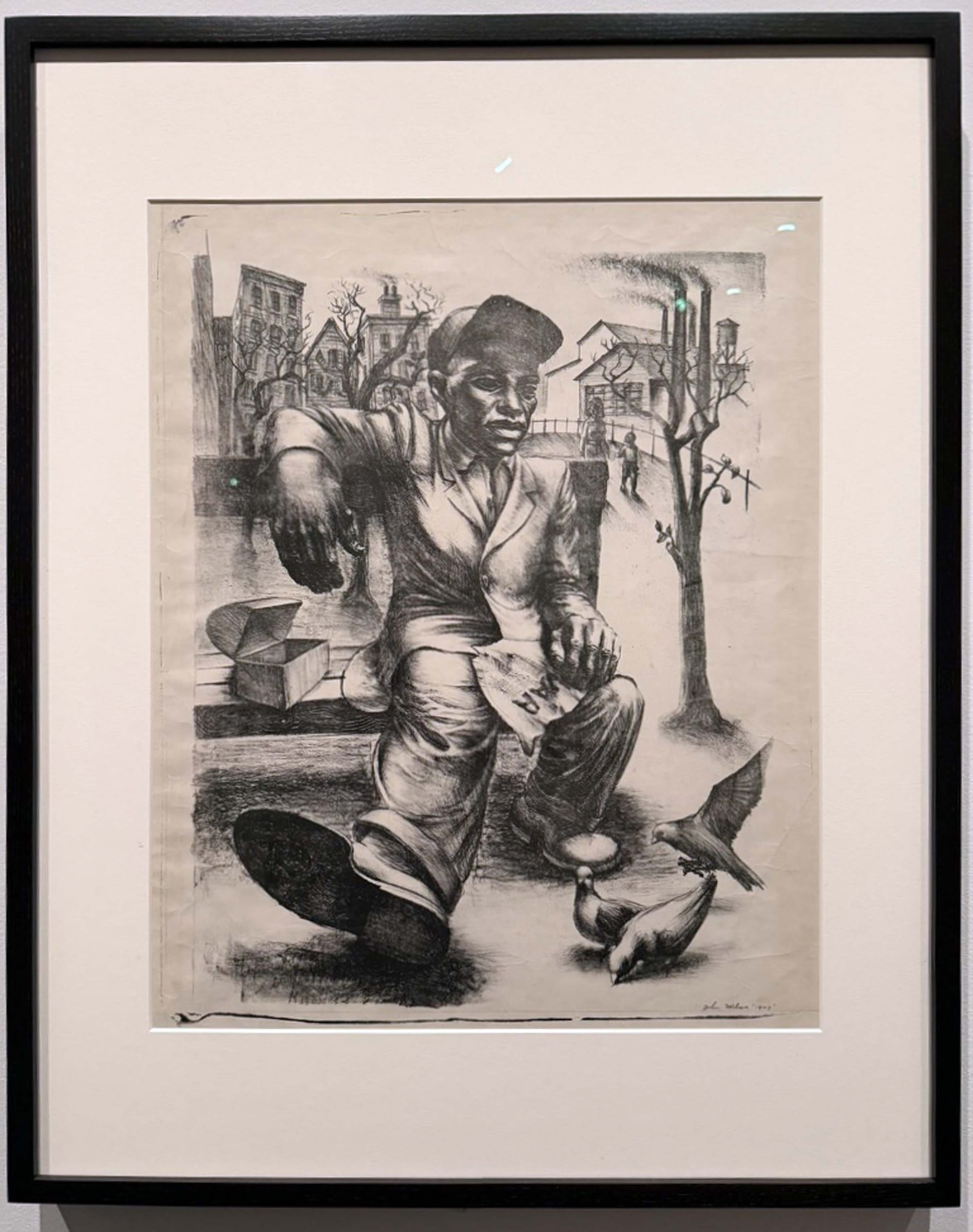

Considered in tandem with Wilson’s earlier lithograph “Breadwinner” (1943), the terror present in “The Incident” shatters illusions of emancipation narratives. In the former, a man dressed for factory work is foregrounded, sitting on a park bench, his hands disproportionately enlarged, highlighting their capacity for labor. His gaze, distant, suggests exhaustion, the weight of the world on his shoulders. A newspaper on his lap has one screaming headline: “WAR.” A woman and child walking in the background remind us of the role, implicit in the work’s title, that he must fulfill. Together, these works suggest an interesting continuity between the violence that followed the end of slavery to the emancipated Black worker, implicitly questioning the reality of being “free” in mid-century liberal America.

Wilson’s work remained in conversation with Wright his entire life. In 2001, at nearly 80 years old, Wilson developed The Richard Wright Suite, a series of aquatint etchings for Wright’s novella, Down by the Riverside, featured in his first book. In the afterword of an illustrated edition made that same year, Wilson wrote of being drawn to Wright’s “powerful, trenchant short stories,” saying he “felt a strong sense of brotherhood” with the characters.

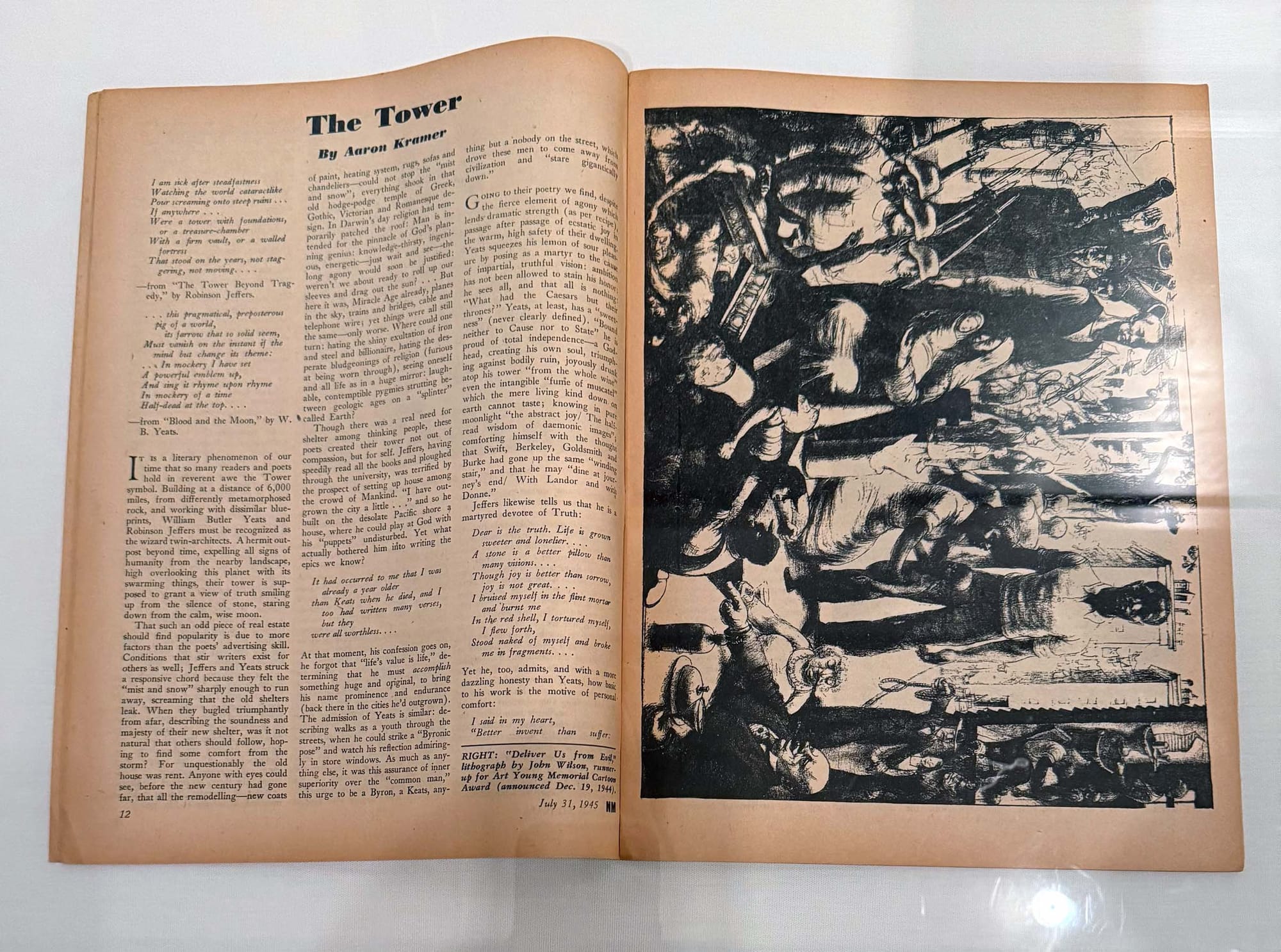

At the start of his career, Wright submitted poetry and journalism to leftist periodicals like the influential New Masses, where Wilson’s art would also feature. In 1945, the magazine reproduced “Deliver Us From Evil” (1943) a lithograph connecting the atrocities of WWII with the racial violence occurring in the United States. This work is one of a series developed in the 1940s, wherein war, too, is defined by the exploitation of the working and oppressed classes and has racial implications back home. This is personified in two oil paintings on Masonite: “Black Soldier” (1943), a striking family portrait in which the eyes of a mother, father, and son each tell a different story, and “Black Despair” (1945), a simple portrait of a soldier at the end of his rope, hunched over a table, face obscured by his arms, his fist clenched.

In 1946, when he was in his 20s, Wilson received fellowships that enabled him to study abroad in Paris with the French Modernist Fernand Léger, and at the Taller de Gráfica Popular in Mexico City, where he encountered the Mexican painter José Clemente Orozco, who hugely influenced his style and philosophy as an artist. Compared to “Breadwinner” and earlier works that meditated on the alienation of the Black worker in a White society, Wilson’s lithographs made abroad were more celebratory of the labor and potential of the worker. He even extended this reverence to the production of art itself in “The Painter” (1947–48), depicting an artist atop a ladder, deeply engaged with the stroke of his brush as he paints a mural.

It’s striking that Witnessing Humanity arrives at a moment when the threat of state terror seems to have reached a tipping point, galvanizing workers to use their collective power to fight back. In response to the recent slayings of protestors by ICE agents in Minneapolis, Minnesota, a general strike — “no work, no school, no shopping” — took place across the country last Friday, January 30. In these events, I’m reminded of Wilson’s gouache painting “Strike” (1946) — currently on display at the Minneapolis Institute of Art — depicting an interracial group of laborers raising signs and demanding justice from a system that exploits every worker. Wilson’s retrospective, indelibly linked with the vision of Wright, is a rejoinder to critics who reject protest art, reminding us that artists are at their most imaginative when they follow their own inspirations — be they ideological, literary, or otherwise.