Israel's Plan to Artwash Genocide at the Venice Biennale

The artwork at the heart of the pavilion promises to continue the project of denying Palestinian existence.

Since the beginning of the full-scale genocide in Gaza, which has galvanized resistance worldwide, the Israeli pavilion of the Venice Biennale has been mobilizing to art-wash the nation’s brand.

Two months before the opening of the 2024 Venice Biennale, a petition written by the Art Not Genocide Alliance (ANGA) and signed by thousands of artists and curators called for the exclusion of the “Genocide Pavilion” and claimed that it represented a state “engaged in ongoing atrocities against Palestinians.” Large demonstrations accompanied the call, which echoed Palestine solidarity campaigns launched by artists at the 2015 Venice Biennale.

Rather than engaging seriously with these demands, Ruth Patir, the artist representing Israel, sidestepped them: Along with curators Mira Lapidot and Tamar Margalit, she taped a sign on the door of the pavilion on the eve before the opening that read, “The artist and curators of the Israeli pavilion will open the exhibition when a ceasefire and hostage release agreement is reached.”

Patir didn’t respond to a request for comment from Hyperallergic about whether she would have opened the pavilion now that these conditions have ostensibly been met. This self-inflicted boycott allowed Patir to perform morality and principle without acknowledging legitimate anti-Zionist Jewish and Palestinian voices or incurring any political risk.

This is the danger of the liberal Zionist position. It offers the language of conscience and dialogue while absolving itself of engagement or responsibility. Patir was able to present herself as ethically conflicted while still accepting the Biennale’s substantial artists’ fee and production money funded by Israel's budget of 1.65 million shekel (~$530,928), all while dismissing calls for cooperation with Palestinian solidarity organizations.

Never required to take a side, never forced to bear consequences, she emerged not diminished, but rewarded. The Jewish Museum in New York City acquired her work (M)otherland, made for that year’s Biennale pavilion, in December of 2024 for an undisclosed amount.

For this year’s pavilion, ANGA reiterated its call for the exclusion of the Israeli pavilion. Still, both the framework and the outcome have been predetermined. To avoid a repeat of the 2024 controversy, the Israeli government introduced a contractual clause requiring the artist to ensure that the pavilion remains open regardless of protest. Art here no longer operates even symbolically as a cover; it functions as a procedural mechanism, carried out through an artist selected for compliance rather than merit. Israel’s participation in this year's Venice Biennale has thus been reduced to a single objective: to insist on visibility at any cost, asserting presence in defiance of a boycott.

This happened in active collaboration with the Venice Biennale management. As the Israeli pavilion is being renovated, the Biennale management offered to host it within the Arsenale — instead of asking Israel to rent a space on the private market, as the other national representations without permanent pavilions do. According to ANGA, instead of responding to calls by artists to exclude Israel, the Biennale management insists its hands are bound while going to great lengths to accommodate the pavilion.

Perhaps unwittingly, management assigned Israel the most fitting space for a pavilion that functions less as an artistic proposition than as a geopolitical gesture: Weapons Room G, dating to around 1460, was used to store arms and to stage Venice’s military power for visiting elites.

Romanian-Israeli artist Belu-Simion Fainaru evidently fit the bill, telling Portfolio Magazine that he is “especially happy to represent Israel in such complex times.” In recent interviews, Fainero has effectively recast a compulsory contractual clause as his artistic mission, declaring to Calcalist: “Even if they protest against us, the Israeli pavilion at the Biennale must not be closed.”

Fainaru, who immigrated to Israel from Bucharest in 1973, embodies the carefully blended contradictions that make him an ideal instrument of cultural soft power. As the Israel Prize Committee put it, his work “combines Jewish symbolism and mysticism, alongside Holocaust remembrance and a universal approach to life and death, wandering and flight, power relations and endless spiraling struggles.” Fainaru frames art as a social mission and the art world as a platform for diplomacy, invoking Jewish-Arab coexistence while insisting, paradoxically, that he “does not operate within political frameworks” and that art’s essence is to “overcome the political, institutional, and diplomatic level.” This ideological minestrone — part universalism, part national myth, part trauma discourse — allows his work to circulate smoothly across institutional and diplomatic contexts.

Most jarring is his insistence on art as redemptive, offering “a desire to live” and a process of “repair and healing” after “Israeli trauma” — language that becomes perverse when set against the ongoing, systematic genocide in Gaza and escalating displacement of Palestinians in the West Bank.

At the Biennale, Fainaru will present “The Rose of Nothingness” (2015), realized for the first time in 2015 at Galeria Plan B in Berlin and exhibited at Art Basel in 2019, developed with musician Iddo Bar-Shai and Sorin Heller of the Hecht Museum in Haifa. “The Rose of Nothingness” is composed of a pool that collects water droplets from a dripper array suspended above it. Framed through metaphors of tears, Kabbalah, and “nothingness,” the work explicitly celebrates Israeli drip-irrigation technology. Commercialized in 1965, the irrigation system has become an emblem of Zionist ingenuity and gives credence to the myth that Israel “made the desert bloom.”

The “nothingness” is an omission in disguise: Israel controls roughly 80% of West Bank water resources, regulating access through permits, infrastructure, and movement restrictions that severely limit Palestinian agriculture while enabling settlement expansion. As the Associated Press reports, illegal Israeli settlers may consume up to 700 liters of water per day, while some Palestinian communities survive on as little as 26 liters per day — exposing irrigation not as a neutral technology, but as a weaponized system of control. “The Rose of Nothingness” thus perpetuates a national myth while ignoring the reality of water being wielded as a weapon of coercion.

The artwork references the 1948 poem “Death Fugue” by Jewish Romanian poet Paul Celan. A haunting poem that pushed the boundaries of form and borrows heavily from the musical fugue composition structure, it describes the horrors of the Holocaust, to which Celan lost both his parents, through dark, evocative imagery that paints a fragmented and twisted picture of reality. Fainaru effectively co-opts the historical suffering of European Jews, sanitizing the imagery in the calm black pool. The musical fugue is defined by recurring motifs and counterpoints, inspiring one line that reappears throughout this poem: “Death is a master from Deutschland.” But the only recurring motif in “The Rose of Nothingness” is its refusal to engage with present-day reality, instead harkening back to the Israeli nationalist narrative of a people overcoming a horrific fate and turning into ingenious inventors. The counterpoint that “Fugue of Death” executed beautifully looms outside “The Rose of Nothingness,” stubbornly ignored by Fainaru: It is the exception of Palestine.

It comes as no surprise that Israel would once again seek to artwash its image by reinvoking the Holocaust, which has been used time and again to justify the Israeli genocide in Gaza and weaponize historic guilt in order to distract from the fact that now, death is a master from Israel.

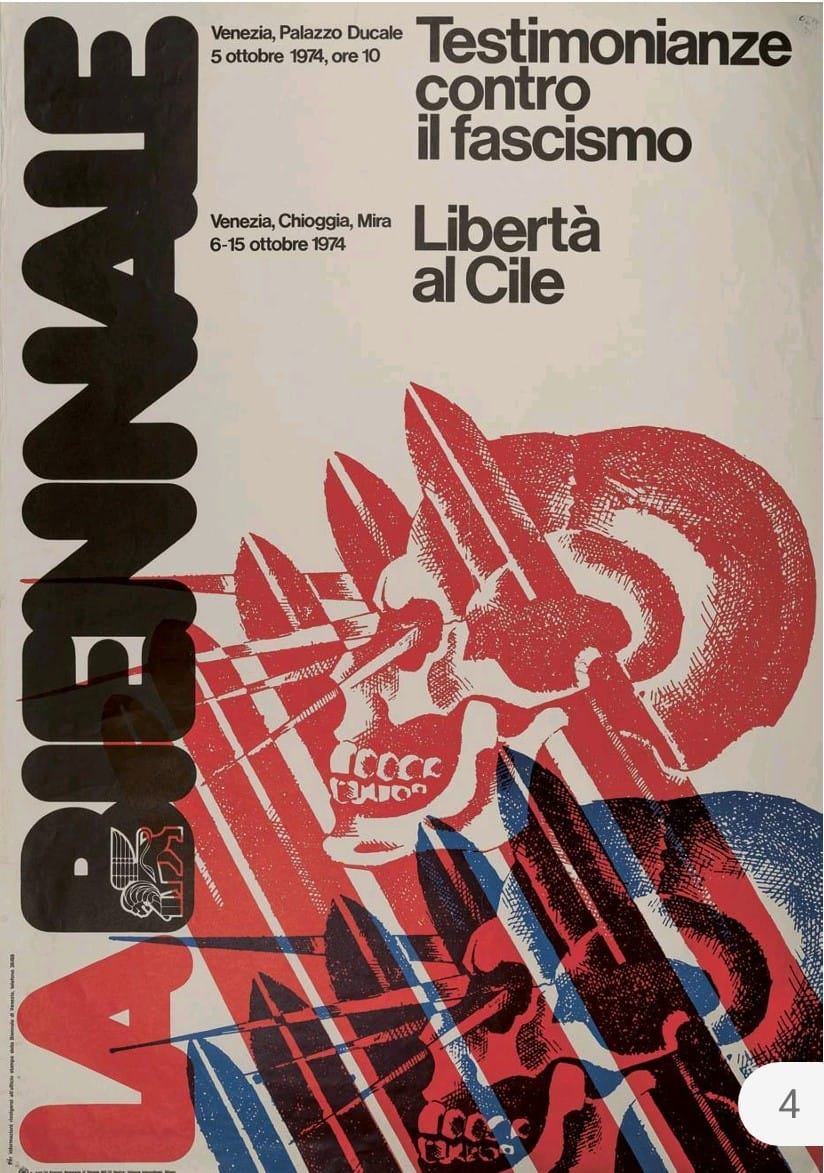

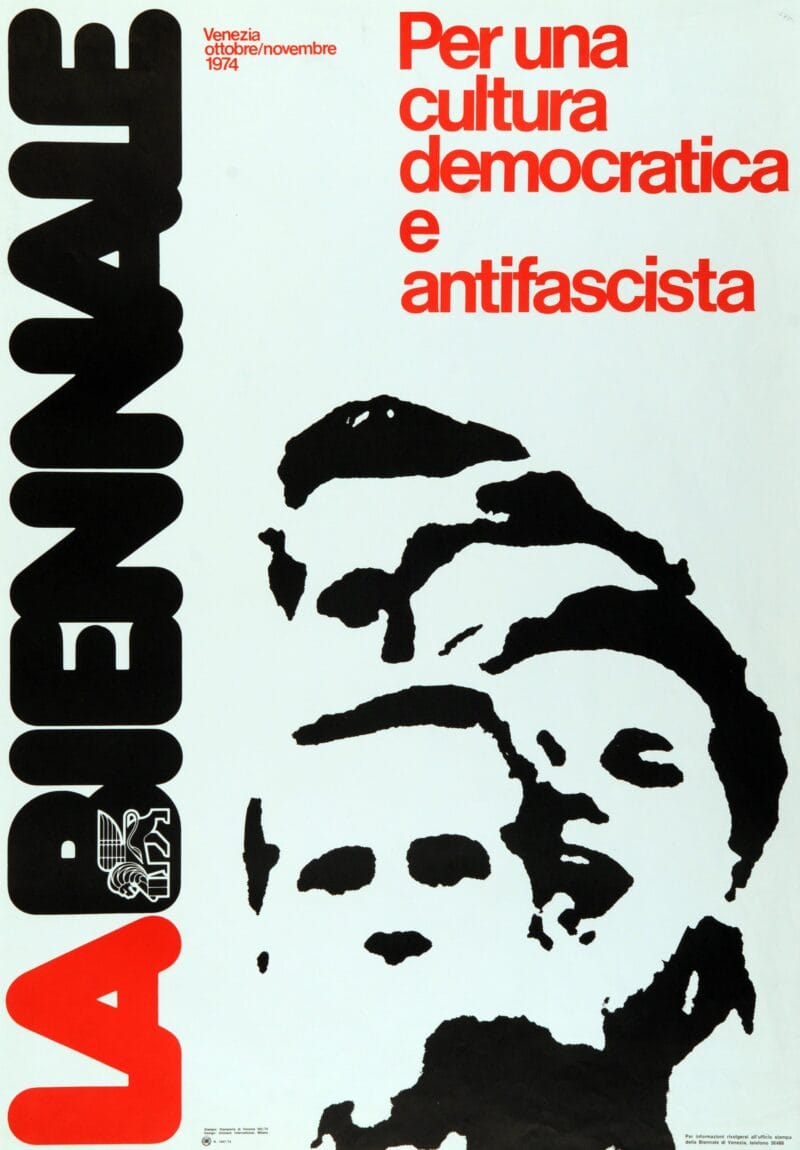

Posters from the 1974 Venice Biennale as a Chilean solidarity forum, held by Disobedience Archive (images courtesy Marco Scotini)

As ANGA argues, the Venice Biennale has never been the neutral space it now claims to be. In 1974, in response to the Pinochet dictatorship, artists and curators demanded solidarity with Chilean dissidents. The Biennale responded by abandoning its traditional exhibition format and reconstituting itself as a political forum. This remains one of the very few moments when a major global art event voluntarily suspended its aesthetic mission in order to confront an urgent political reality.

That same year, South Africa was effectively excluded from the Biennale. The cultural boycott was widely understood as a refusal to legitimize apartheid through art and was sustained for nearly two decades. In both cases, the Biennale recognized that neutrality was itself a political position — and chose a side.

The last two years have exposed the fragility of any claim to universal human rights and the inability of United Nations bodies to enforce them. They have also revealed uncomfortable geopolitical truths and produced painful ruptures in personal and professional relationships, in the art world and beyond.

Within this context, the Venice Biennale’s current posture lays bare the cynicism of the art world. Where it once acted decisively, it now bends over backward to avoid offending Israel and the United States. In doing so, it becomes complicit in ongoing genocide — despite the outcry of tens of thousands of artists and of the 40% of announced national pavilions that have signed ANGA’s letter calling for the Israeli pavilion’s exclusion. What remains is not resistance, but the aesthetic window-dressing of violence.