Ken Gonzales-Day Centers History's Margins

A mid-career survey spans three decades of studying and responding to the absence of gay and Latinx people from historical records.

LOS ANGELES — Ken Gonzales-Day is both an artist and a scholar: Most of his art projects result from extensive research, and some have been published in book form. As revealed in the illuminating exhibition History’s "Nevermade" at the University of Southern California's Fisher Museum of Art, Gonzales-Day has spent over three decades studying and responding to the absence of people like himself — gay and Latinx — from historical records. As the Trump administration attempts to purge any such content from the Smithsonian museums, a presentation of the artist’s projects could not be any timelier.

Gonzales-Day’s earliest project of note addresses the dearth of references to people of color in documents and literature chronicling the history of the American West. Consisting of photography, sculpture, installation, and a book of fiction purportedly written by the protagonist, Bone-Grass Boy: The Secret Banks of the Conejos River (1986/2017) is an account of a two-spirit author of a faux autobiographical novel set in the 19th-century Southwest. In the photographs, which are presented salon-style, and a facsimile of the book, Gonzales-Day used digital processes to transform himself into the central figure, Romancita — as well as all the other characters.

While troubled over the Bush administration’s immigration policies in the early aughts, Gonzales-Day began researching the little-known lynchings of Mexicans, Mexican-Americans, Asians, and Indigenous people in California. These studies culminated not only in some of the most poignant photographic work of his career, but also his 2006 book Lynching in the West: 1850–1935. In the photos, which are at once educational and emotionally stirring, he examines environments where lynchings occurred, as well as the people who watched them.

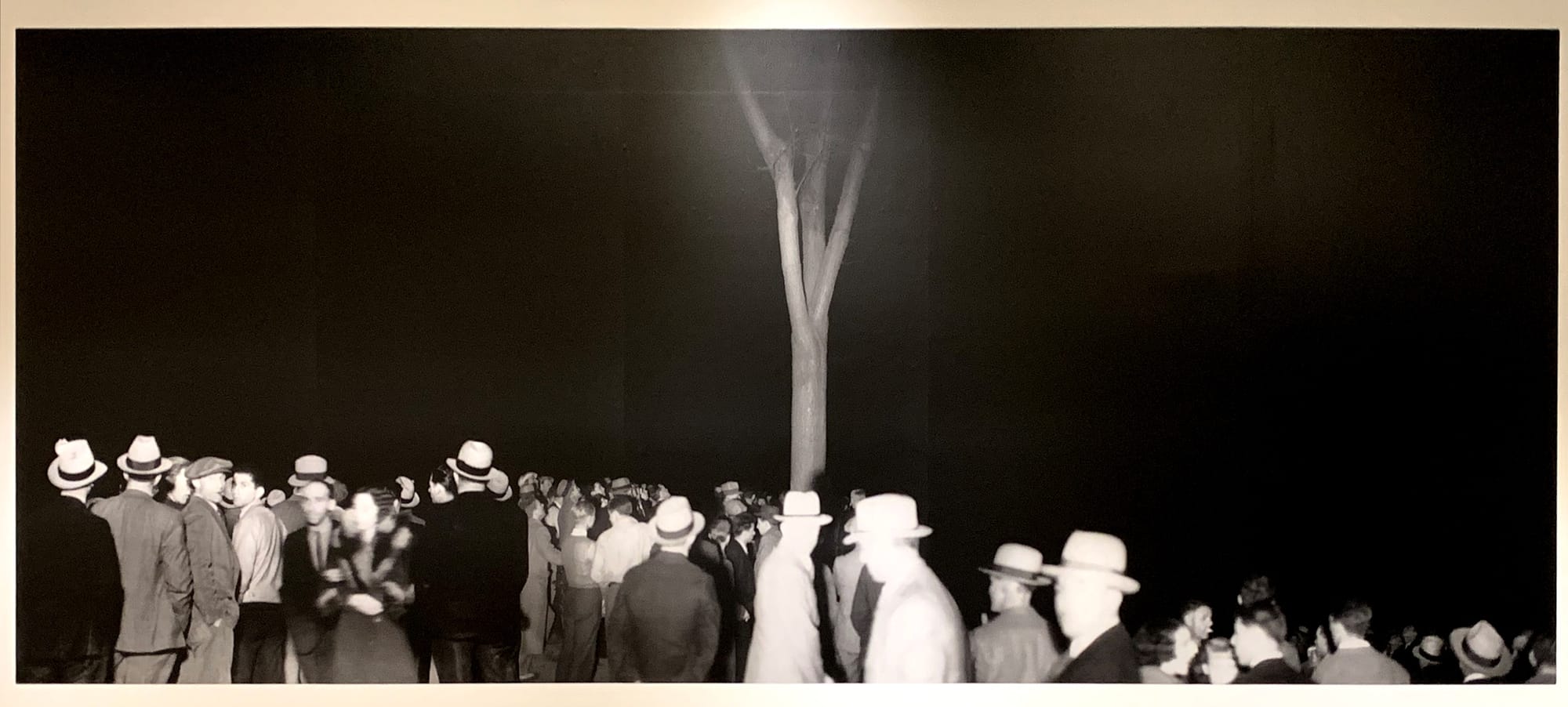

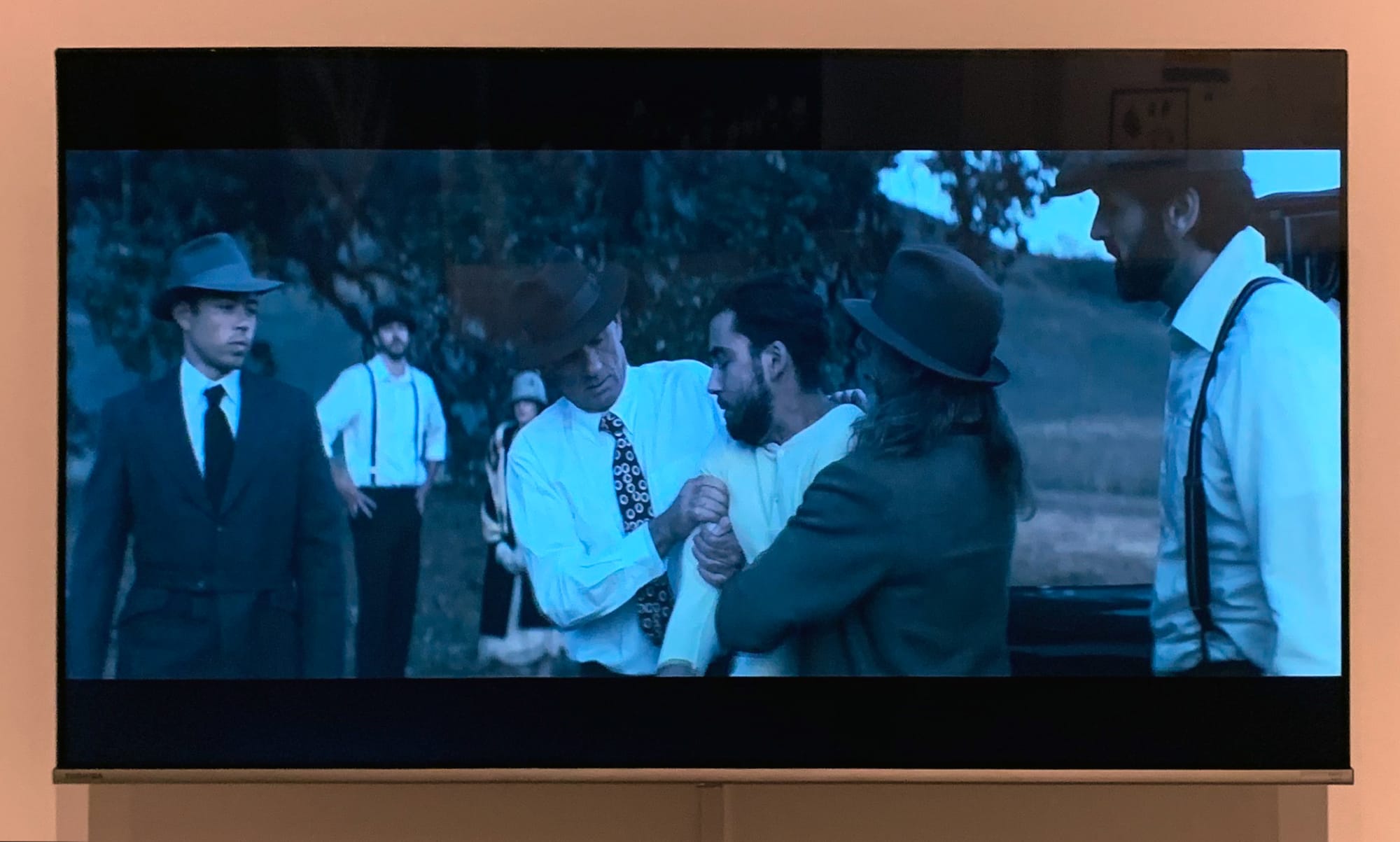

For “Searching for California Hang Trees” (2002–14), he memorialized the trees at probable lynching sites in haunting photographs. In the ongoing Erased Lynching series (begun 2002), he digitally removed the victims from historical photos, as in his reworking of a panoramic image of a crowd witnessing a 1933 lynching, and in several facsimiles of 19th-century postcards depicting the horrific events. In these works, the removal of victims suggests multiple metaphors: their deaths, their erasure from history, or the fact that their lives were considered valueless in that time and place. The riveting staged lynching reenactment video “Run Up” (2015) seems to counter that emptiness with presence, lingering on the troubled facial expressions of spectators, including victims’ family members and friends.

Gonzales-Day has also explored racial bias in museum collections, which tend to favor work depicting White subjects by mostly White male artists. For a photograph from his ongoing Profiled series begun around 2009, he arranged sculptural figures from the Getty Museum in a linear progression from white to black, based on the objects' color. Cleverly, he set them against a black backdrop to form a subtly detectable section of a rainbow, thereby reinforcing the harmony and shared humanity between people of different cultures and skin colors.

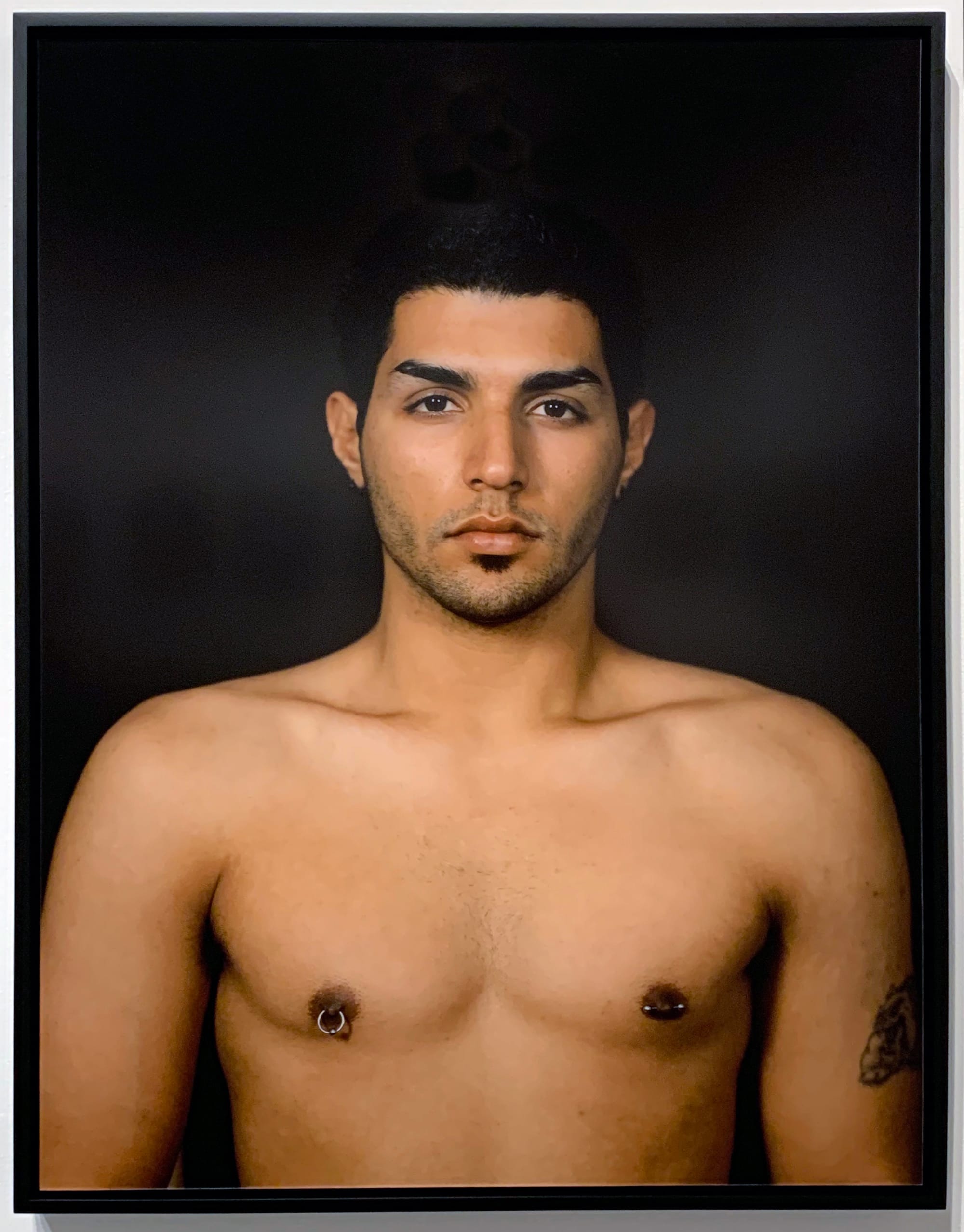

A similar empathy is evident in Gonzales-Day’s photos of Latinx men, taken after the artist told them about his lynching research, and of mostly queer friends and colleagues, shot with great care during the COVID-19 pandemic. The artist’s goal is to capture moments of comfort and trust between him and his subjects, which is apparent in works such as “Aaron” (2006), in which a bare-chested tattooed man with pierced nipples appears both vulnerable and saintly. Indeed, in a moment when the term “woke” is wielded either ironically or pejoratively, Gonzales-Day’s art reminds us that caring about those who are different from us is really a thing of beauty.

Ken Gonzales-Day: History’s “Nevermade” continues at the University of Southern California Fisher Museum of Art (823 West Exposition Boulevard, Los Angeles, California) through March 14, 2026.