Sitting Bull S***: Kent Monkman at the Glenbow Museum

Gender issues and neo-colonialism are having a fine frippery field day courtesy of Kent Monkman a gay First Nations Manitoba Swampy Cree Canadian artist … is part of a small, but burgeoning contingent of Canadian First Nations artists who are engaging in sociological and scatological commentary on t

Gender issues and neo-colonialism are having a fine frippery field day courtesy of Kent Monkman, a gay First Nations Manitoba Swampy Cree Canadian artist. Monkman’s mother is English and Irish. His father is a Christian Cree who delivers sermons from a Cree language bible, so the man has got First Nations, British, Irish and gospel blood pouring through his latticed veins. Whether waving his pink boa feathered headdress around as his performance art alter ego, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle (punning “mischief” and “egotistical”), filming much more serious documentary subjects concerning First Nations issues, or painting a faux gender bending 19th Century tableaux, he is part of a small, but burgeoning contingent of Canadian First Nations artists who are engaging in sociological and scatological commentary on the state of the nations, First or otherwise.

Most people reading this review may not be that familiar with Calgary, site of the 1988 Canadian Winter Olympics, or as I like to call it, Houston in the Rockies. Oil, gas and beef are big here, so big that China just went on a shopping spree and scarfed up a big slice of the province’s controversial oil sands. The most popular yearly event is the Calgary Stampede, the largest rodeo in the world. For all its money and might, Calgary has just one museum in town, the Glenbow, given over to preserving both First Nations history as well as the history of the settling of the province of Alberta. The Mounties, those red coated constables of old who built the original Fort Calgary used the slogan, “The Mounties always get their man.” That slogan takes on a completely different meaning in the context of Monkman’s exhibition, one I suspect the beef oil and gas locals are not too thrilled about.

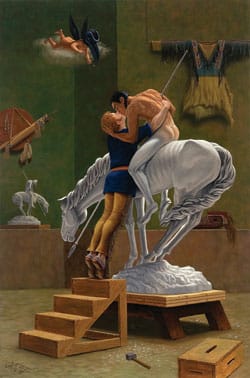

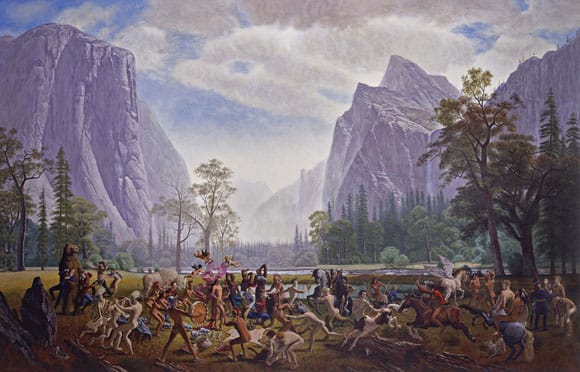

Monkman, whose show at the Glenbow includes oil paintings, sculptural spaces and objects, films, videos and photography, riffs off 19th century landscape painters like Cornelius David Krieghoff. Krieghoff’s painting in the Brooklyn Museum, “Following the Moose” (1860) or other work, “Indian Wigwam”(1848) puts him at the top of the heap of those who exoticized, romanticized, and fetishicized First Nations people as “noble savages.” With that style as a base he reconstitutes the grand nineteenth-century new world landscape painted by Albert Bierstadt, Frederick Church, and Paul Kane. Monkman’s work looks critically at Western art history, North American colonialism, and world Imperialism in an alternately light-hearted and heartbreaking manner.

He ravishes European Grand Manner painting by inserting “missing narratives and obliterated histories,” and turns young male Anglo cowboy colonizers into gay native sex fantasy objects of desire. As his alter-ego Miss Chief Eagle Testickle, he seduces his subjects with whiskey. When done with them he dresses them up as stellar examples of “authentic European males.” In his performance piece from 2007, “The Taxonomy of the European Male,” Monkman traveled to the Compton Verney, an 18th Century estate in Warwickshire, England. Dressed to the nine’s as Miss Chief (resembling Liza Minelli in Indian drag) replete with a pink, black and white feathered headdress and wicked white Donna Summer disco era platform high heels, Miss Chief discusses the physiology and phrenology of various “tribe of Europe.” Using a specimen at hand he intones “The English are well proportioned people in their limbs, and are quite good looking, being rather narrow in the hips and rather long in the groin. They are a little inclined to stoop.”

Take that, John Wayne.

* * *

It is worth noting that Monkman is not alone in exploring these themes through the perspective of a member of the First Nations. There are at least two other First Nations artists who are exploring similar terrain. The first, Lori Blondeau is a performance artist based in Saskatoon, Saskatchewan focusing on images of the Indian Princess and the Squaw. The other is Buffalo Boy who makes appearances at the Burning Man festival alternately as a shaman dressed in Buffalo robes or a campy drag cowboy.

Kent Monkman’s The Triumph of Mischief was at Calgary’s Glenbow Museum from Feburary 13 to April 25, 2010.