Man Ray Was So Much More Than a Photographer

From film to painting to sculpture to chess, the Surrealist was an artist-inventor, tinkering away at light and objects and having a good laugh all the while.

Stepping into the exhibition Man Ray: When Objects Dream at The Metropolitan Museum of Art feels like entering the bellows of an old camera. Through a rectangular frame cut into the entry, the darkened walls unfold, accordion-like, to reveal a visual feast of the artist’s work, as Man Ray’s earliest film, “Retour à la raison (Return to Reason)” (1923), flickers across the screen opposite. Although the exhibition brings together approximately 160 works from an impressive array of lenders, it reveals itself gradually, taking the viewer through several turns before one can grasp its sheer enormity. When Objects Dream proves, thrillingly, that anyone left feeling jaded from the many, many recent exhibitions surrounding Surrealism’s centennial in 2024 can still see the movement’s key photographer with a fresh set of eyes.

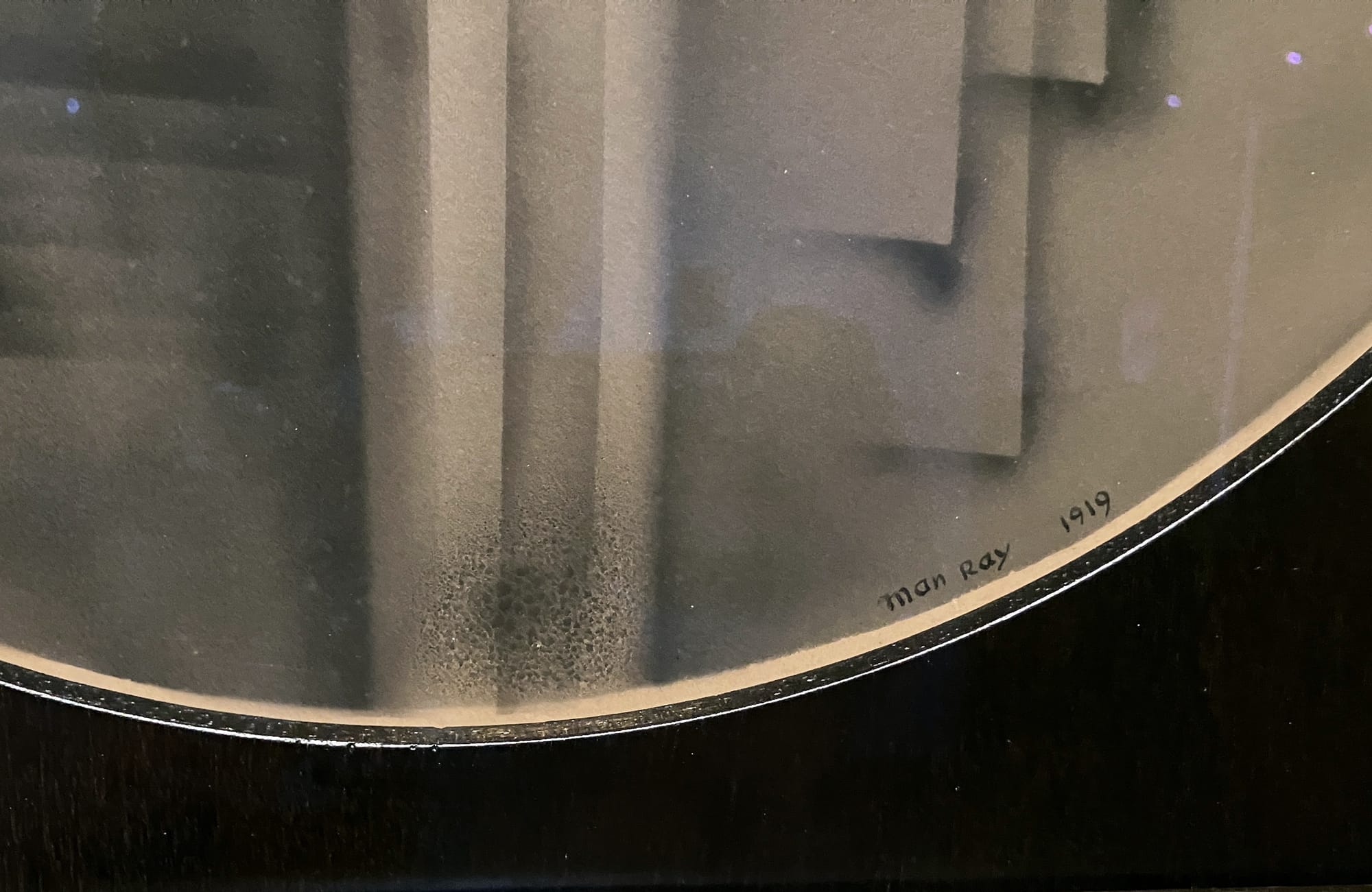

The exhibition opens and closes with Man Ray’s photographic project Champs Délicieux (Delicious Fields) (1922–59) and, at risk of being corny, the prints are indeed très délicieux. Though the “rayographs” — photographs taken without a camera by directly exposing objects on light-sensitive paper — dematerialize their objects, turning them into ghostly dreams, seeing the works in person allows one to recover the wonderful materiality of the prints themselves — splashes of darkroom chemistry, whorls of fingerprints, the uneven application of airbrushed paint. Even the creases at the top of “La femme (Woman)” (1918–20) remind us that these works are living objects. This was as Man Ray himself intended, as the Surrealists constantly played with tactility in their work; the more interactive features of the exhibition, like the spinning print turnstile of “Facsimile of Revolving Doors” (1919), likewise honor this principle.

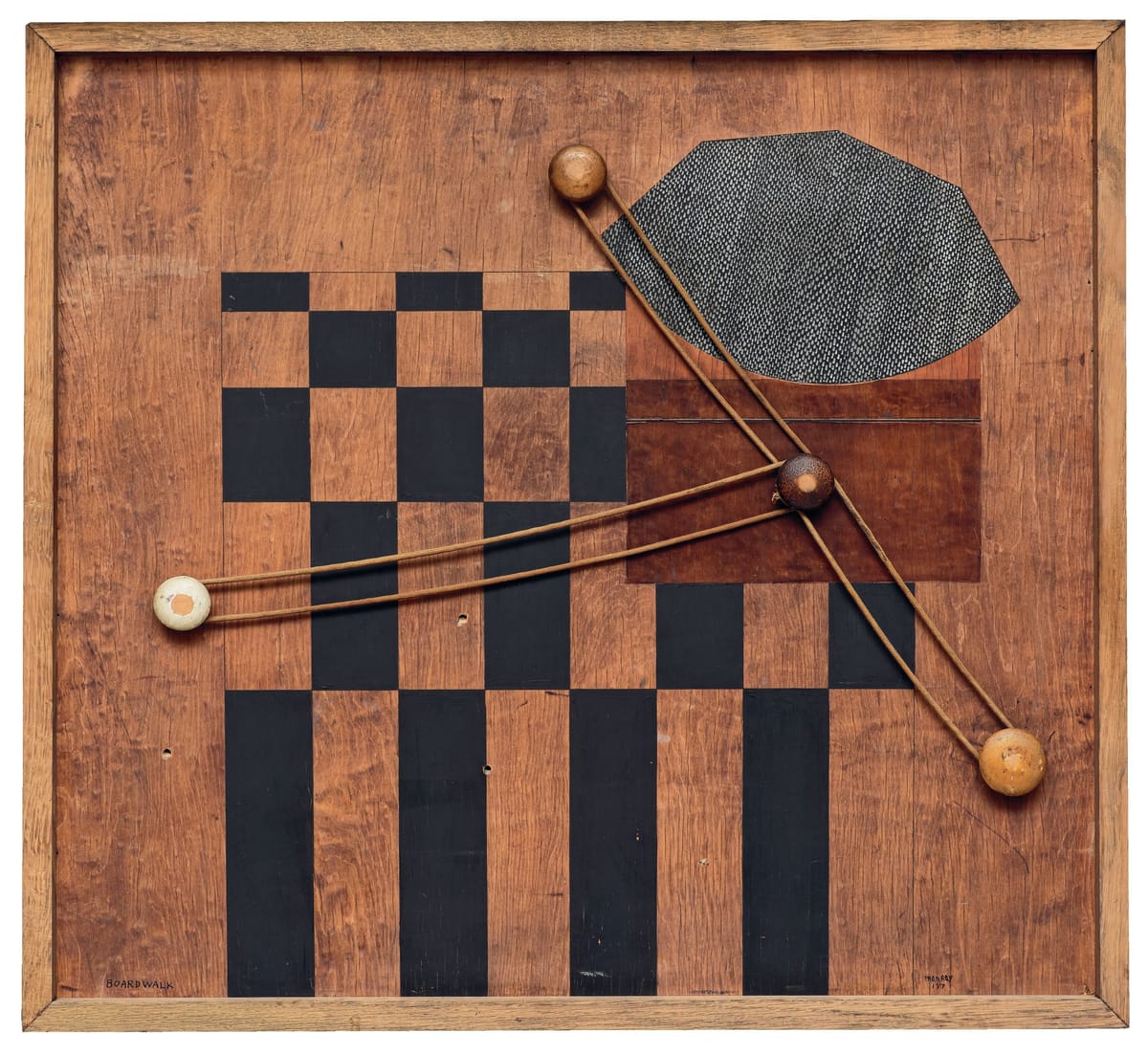

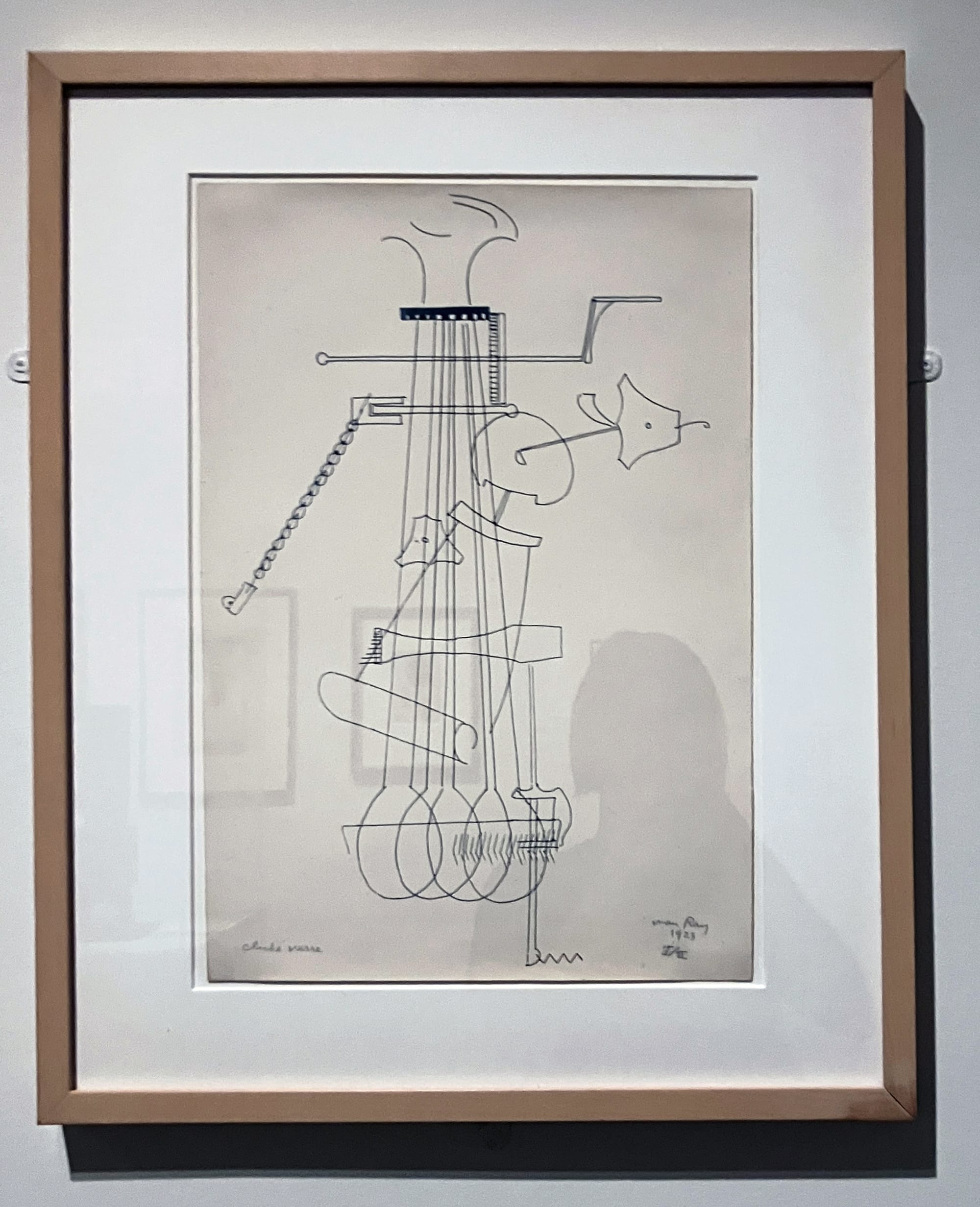

While the exhibition centers Man Ray’s 1920s rayographs, it shows that the Surrealist was so much more than a photographer. This is demonstrated not just by the vast array of media on view — from film to painting to printmaking to stereography to sculpture to chess and back again — but also through the way these works are arranged and described by the wall text. Man Ray’s cleverly phallic portrait of an egg beater, “L’Homme (Man)” (1918), hangs across from his cliché-verre “The Egg Beater” (1923), which looks like the technical drawing for some kind of Rube Goldberg machine. The pattern of a cheese grater appears in a painting, and reappears as an impression on a rayograph, while the films animate the still photographic impressions. Man Ray thus comes across less as a photographer — though this remains his greatest legacy — and more as an artist-inventor, tinkering away with light and objects and having a good laugh all the while.

My one quibble is with the museum’s curious decision to completely omit the word “photogram” from the exhibition. (The press release explains this distinction, though I did not see it written anywhere in the wall text of the physical show.) Though “photogram” is the primary term for an image taken by placing objects on light-sensitive paper, most casual visitors will leave the exhibition under the misguided impression that Man Ray’s neologism “rayograph” is the word for this practice — though the artist was pretty much the only person who called it that. While it makes sense to use this bit of self-branding to describe Man Ray’s own process, one would think that it might be worth giving such context for the central body of work in the exhibition (Man Ray was not the only person making photograms in the 1920s, after all). These kinds of entrepreneurial self-stylings have a long history in photography, including Louis Daguerre’s daguerreotype and Henry Fox Talbot’s talbotype. Man Ray’s work stands up tremendously well against the history of photography writ large — he doesn't need The Met to bolster his brand.

Man Ray: When Objects Dream continues at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1000 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through February 1, 2026. The exhibition was curated by Stephanie D’Alessandro and Stephen C. Pinson.