Medieval Psalms Were Not For Everyone

An exhibition prioritizes the expensive, silent object over the lived, functional experience of the believer.

Sing a New Song: The Psalms in Medieval Art and Life at the Morgan Library & Museum sets out to trace the impact of the Psalms on “men and women in medieval Europe” from the 6th to 16th centuries. But while the exhibition offers a beautiful and instructive display of manuscript artistry, it risks presenting a sanitized vision of the book's history, one that glosses over the fundamental power dynamics and conflicts inherent in medieval religious life. By framing these "gloriously illuminated" Psalters as impacting Medieval men and women in general, the exhibition risks creating the illusion of widespread engagement and access. In reality, these breathtakingly expensive manuscripts were tools of the elite.

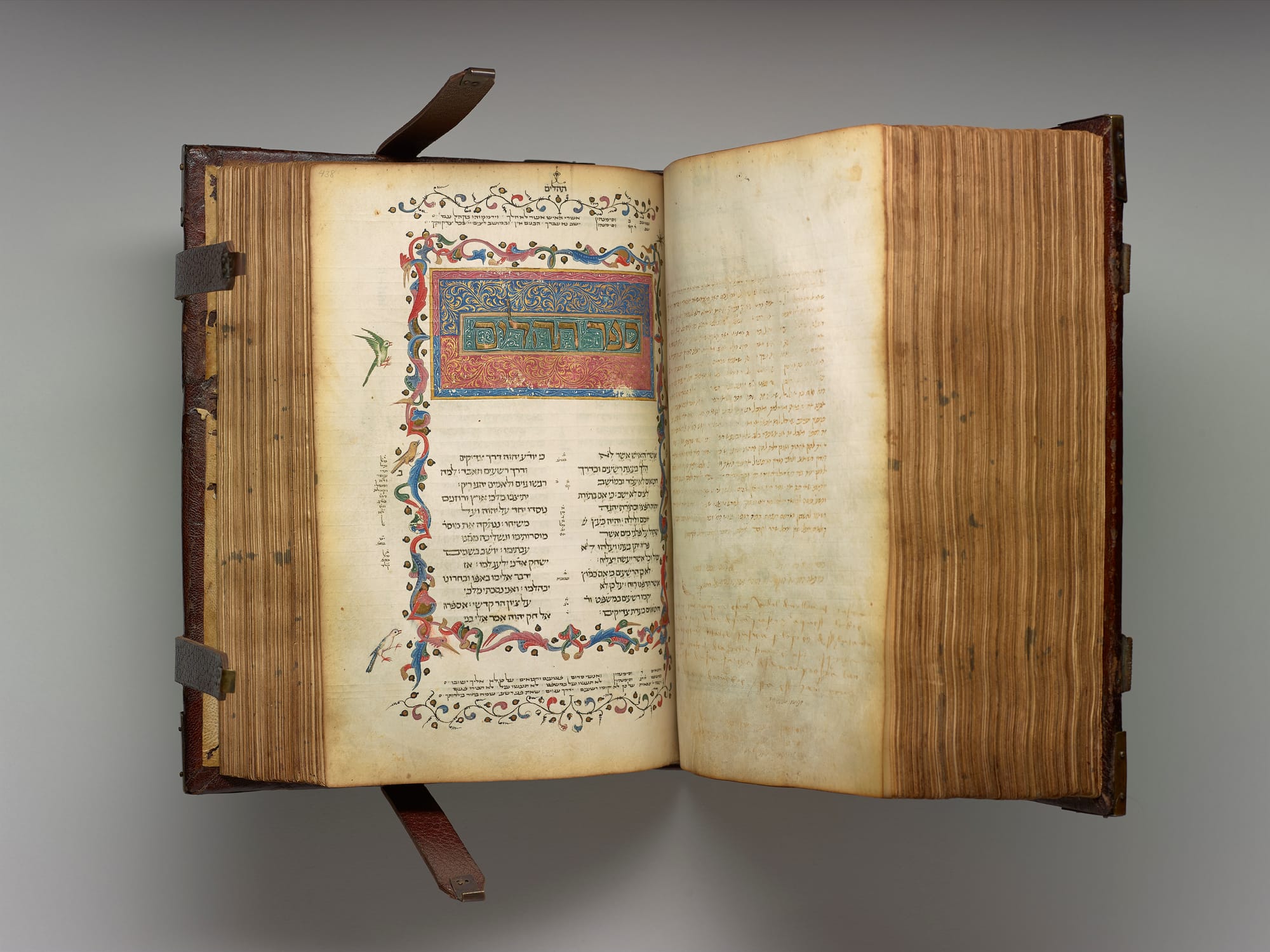

The Book of Psalms (often called “Psalms" or the “Psalter”) is a central book in the Jewish Bible (Tanakh) and the Christian Old Testament. At its core, it is an anthology of 150 sacred Hebrew poems, songs, and prayers that were originally set to music for use in temple worship and often attributed to King David, though there were many authors. The English term “Psalms” derives from the Greek word psalmoi, which originally meant “songs sung to stringed instruments.” In the Jewish tradition, the book is called Tehillim (meaning “Praises”).

The text is therefore a shared inheritance between Judaism and Christianity. However, as the introduction to the exhibition implies, the interpretative framework between the two is fundamentally different. The Christian approach is predominantly framed around Christ himself, viewing the Psalms as Messianic prophecies that prefigure His life, suffering, and triumph — a lens sharply different from the traditional Jewish focus on their original liturgical and historical context.

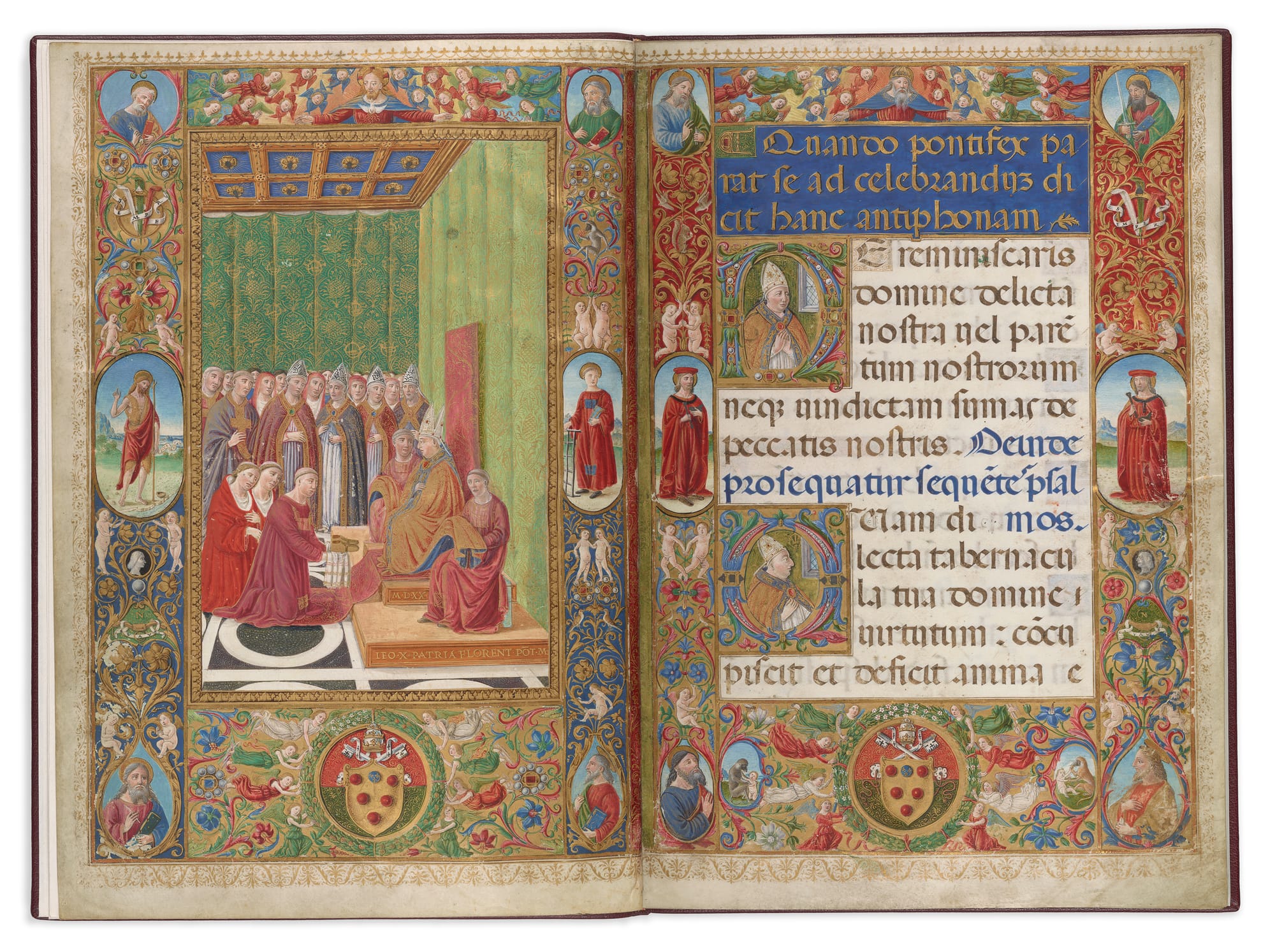

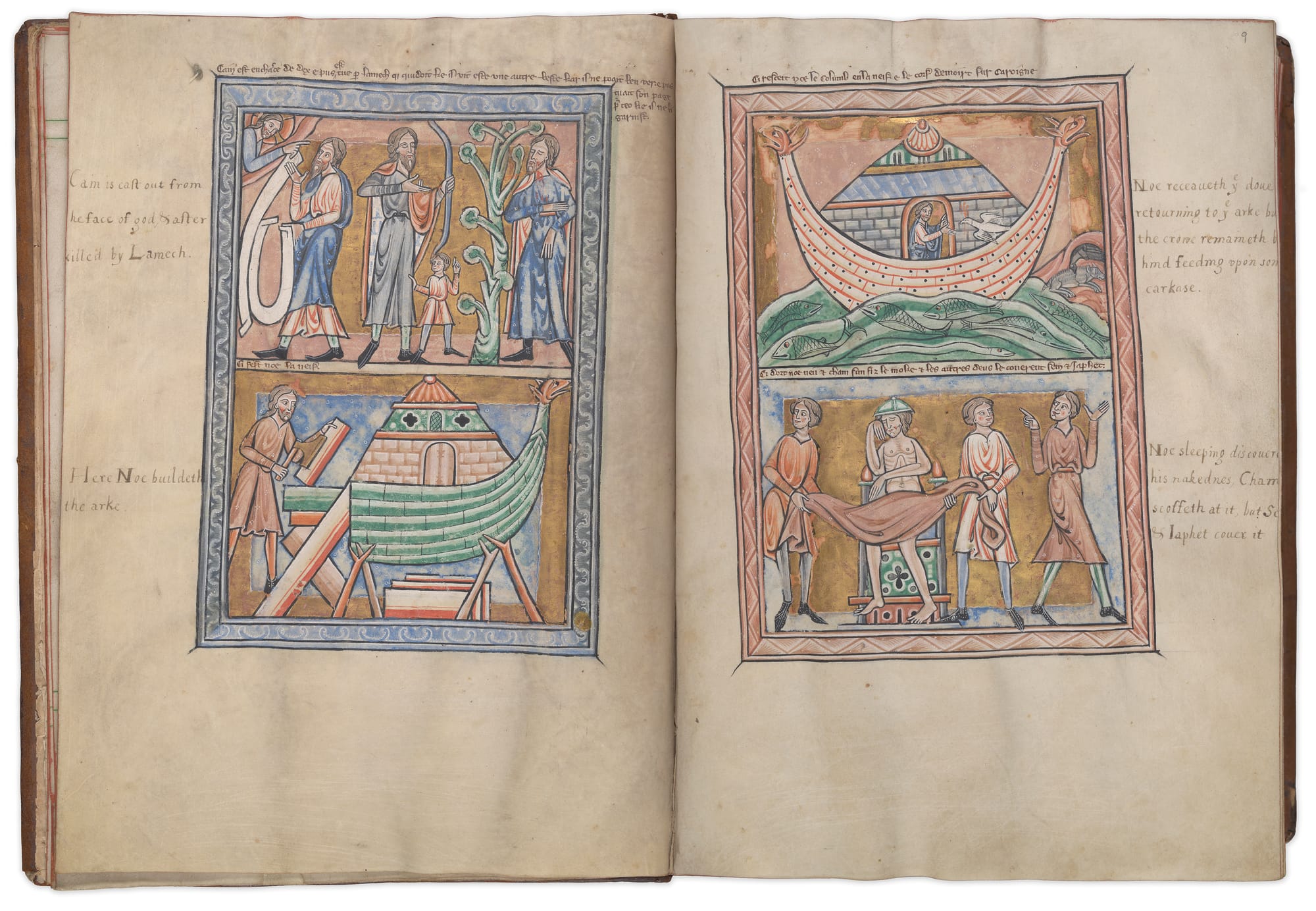

The exhibition attempts to bridge this difference by organizing its impressive selection of manuscripts, printed texts, and devotional objects across five thematic sections. The first, “Translating the Psalms” highlights the movement of the Psalter into diverse languages (Latin, Greek, Middle English, Amharic, Hebrew and Aramaic), ostensibly focused on how communities with linguistic differences adopted the text. “Teaching the Psalms" explores the Psalter's role in monastic and clerical learning across Europe, including commentaries and liturgical books. Here, the inclusion of texts associated with noblewomen — such as a French commentary from Belgium (c. 1200) by Simon de Tournai written for the noblewoman Laurette d’Alsace, daughter of Count Thierry of Flanders — attempts to frame the Psalter as a gateway to female literacy and learning under the misleading heading “Women and Learning.”

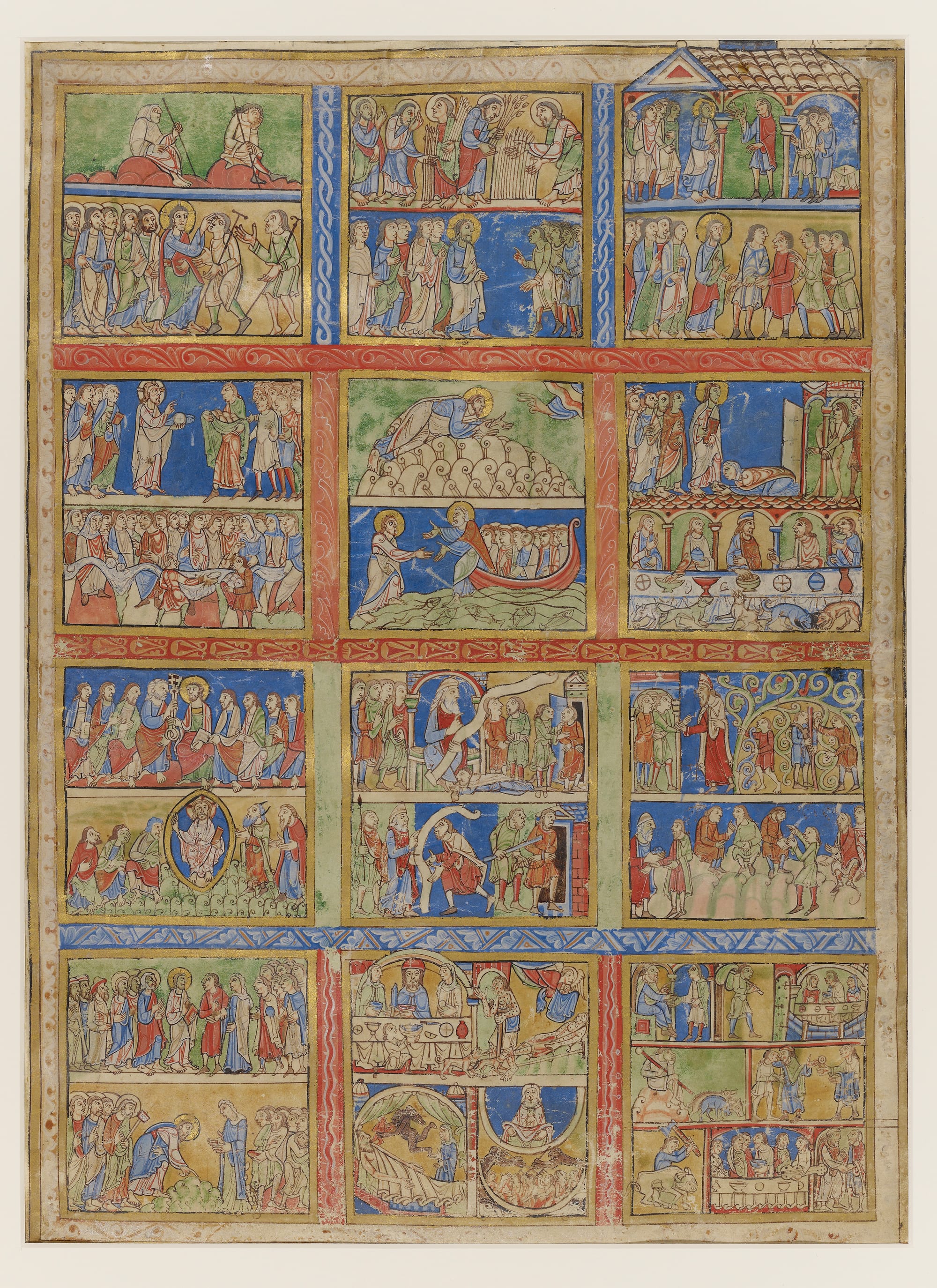

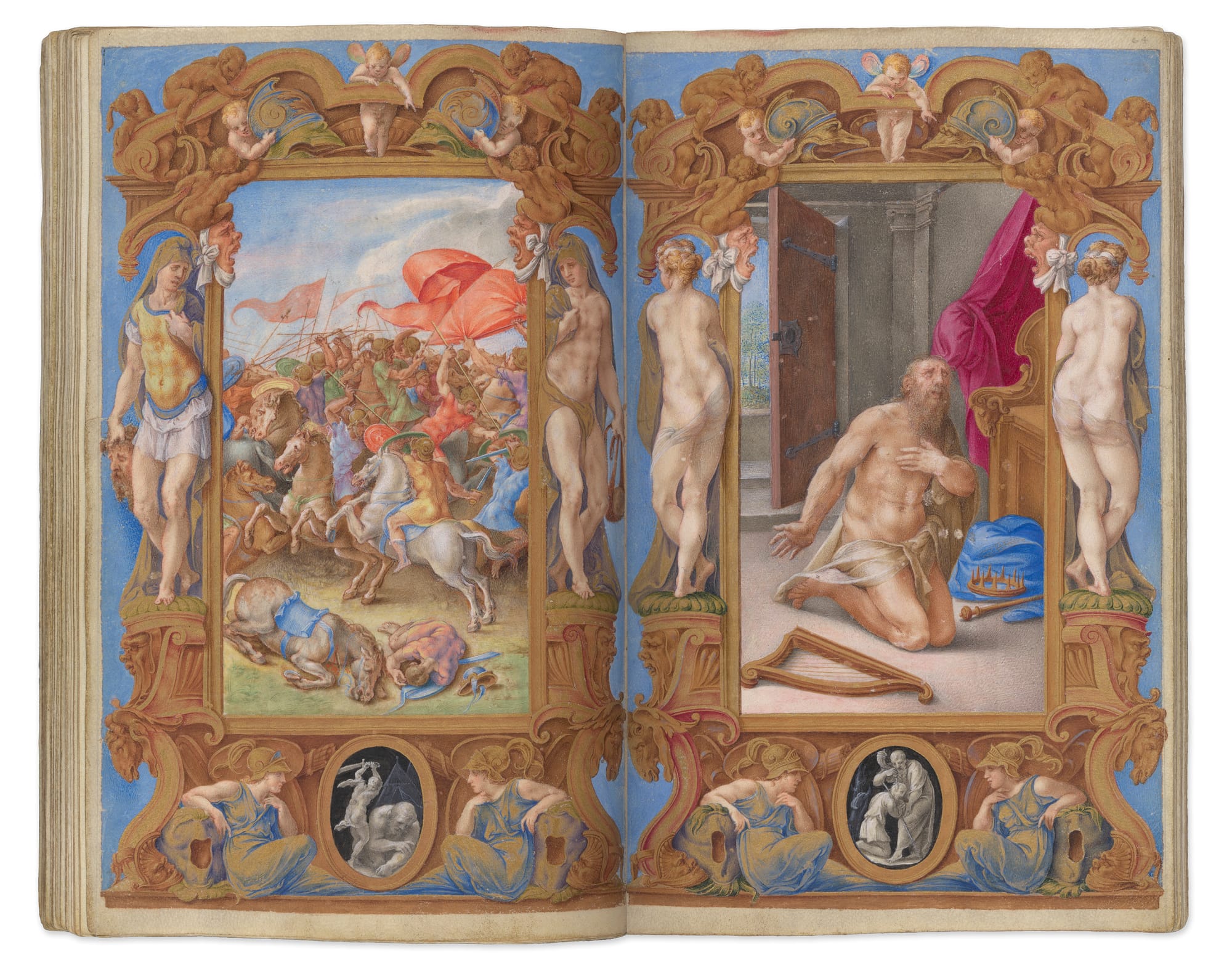

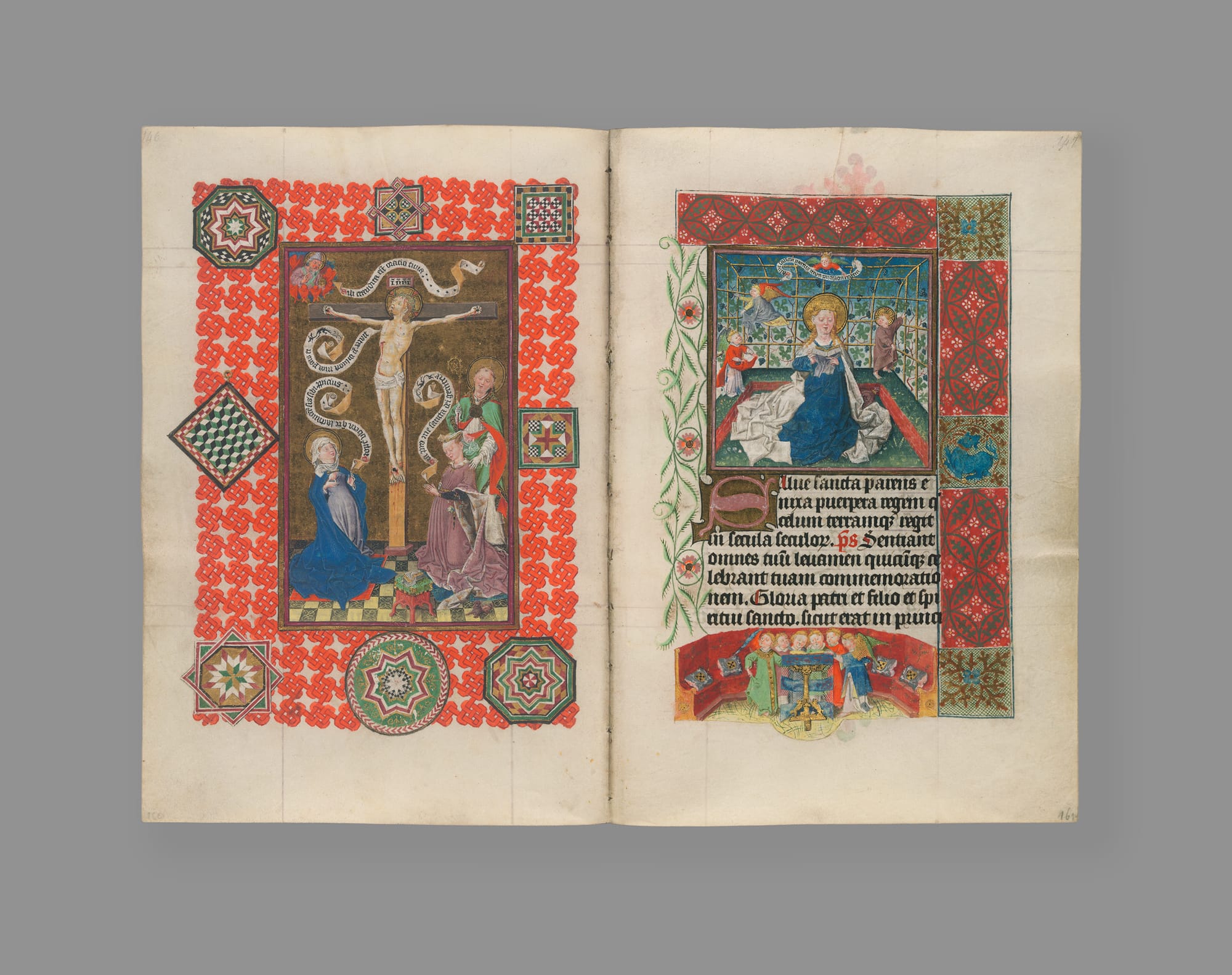

The section “Illuminating the Psalms” showcases lavishly decorated Psalters, including famous “greatest hits” like the Eadwine Psalter from Canterbury, England (c. 1155–60) and the Lewis Psalter from Paris (c. 1225–30), emphasizing the artistic tradition of medieval manuscripts. “Performing the Psalms” considers how the large, unadorned choir books — or Antiphonaries, mostly from parts of Italy — were used in daily monastic or clerical offices. Finally, “Using the Psalms” concludes by examining the Psalter’s secondary functions, such as the warding off of evil, illustrated by objects like a fascinating amulet prayer scroll in Greek and Arabic from Trebizond, in the Byzantine Empire (c. 14th century).

But while these books are certainly beautiful and instructive, presenting them as impacting the ordinary “men and women in medieval Europe” is inaccurate. The aforementioned Lewis Psalter and similar examples were not tools for the "everyday spiritual life of the peasant," as the curators suggest in the wall text. They were commissioned by the nobility and royalty. Their construction required enormous resources — hundreds of animal skins for the vellum, the labor of multiple specialized artisans (scribes, illuminators, binders), and costly pigments like ultramarine (lapis lazuli), which was often more expensive than gold. The educational value of the Psalter for the vast majority was limited to rote, catechetical instruction — they were not a gateway to broader literacy or social mobility. By emphasizing these lavish objects, the exhibition becomes more a celebration of aristocratic patronage and clerical control than a true reflection of average medieval spirituality.

The section “Translating the Psalms” implies a natural, cohesive progression of the Psalter into diverse communities. However, this process was deeply political, disruptive, and frequently met with suspicion and hostility from the Church hierarchy. The most direct example of this hostility is the Constitutions of Oxford (1408), a set of rules issued by Archbishop Thomas Arundel. This decree was directly aimed at suppressing the Lollards — the followers of English reformer and Catholic priest John Wycliffe — by explicitly restricting access to unauthorized English translations of the Bible, including the Psalms. The Constitutions mandated that no one should translate or read any scripture into English without episcopal approval, effectively criminalizing lay ownership of the Wycliffite Psalter and formally linking vernacular scripture to heresy. This act demonstrates that the Church often viewed the Psalter in the common tongue not as a devotional aid, but as a source of subversive, unapproved theological interpretation.

The decision to align diverse languages and cultures side-by-side in the exhibition, without acknowledging the periods of intense ethno-religious conflict, also suggests a misleading uniformity. During the Middle Ages, the Christian interpretation of the Psalms was frequently marshaled as a theological weapon against Judaism. Medieval Christian polemicists commonly interpreted the Imprecatory Psalms (those containing prayers for divine vengeance, such as Psalm 69 or Psalm 109) as prophesying the suffering and damnation of the Jewish people for their refusal to accept Christ. For example, Psalm 109:6–13 was often allegorically interpreted as a curse against Judas Iscariot and, by extension, the entire Jewish community. This theological framework was used to justify policies of persecution and segregation, a crucial, messy reality of the Psalter’s use in medieval Europe that is omitted when stressing only "universal themes.”

The exhibition's title, Sing a New Song, and the section “Performing the Psalms” emphasize the auditory "performance" of the text — how the Psalms were chanted, sung, and integrated into the daily offices. Yet the exhibition’s primary medium is the manuscript, an object that is inherently silent and visually focused. The display overemphasizes the physical relic (the luxurious book) while failing to fully reconstruct the ritualistic context that defined the Psalter’s primary function in medieval life. By not bridging the divide between the visual relics and the performed ritual — for instance, through accompanying audio loops of Gregorian chant or monastic recitation — the presentation ultimately prioritizes the expensive, silent object over the lived, functional, and auditory experience of the medieval (and illiterate) believer.

This exhibition at the Morgan Library succeeds admirably as a showcase of glorious manuscript illumination and aristocratic devotion. However, in its effort to present a seamless, universally embraced history, it glosses over the critical realities that defined access to and interpretation of the Psalms: the breathtaking cost that restricted them to the elite, the political and ecclesiastical suppression of vernacular versions, and their use in justifying the marginalization of Jewish communities. The exhibition’s primary emphasis remains on the luxurious visual object rather than the complex, often conflict-ridden reality of the Psalter’s power within medieval life.

Sing a New Song: The Psalms in Medieval Art and Life continues at the Morgan Library and Museum (225 Madison Avenue, Murray Hill, Manhattan) through January 4. The exhibition was curated by Roger S. Wieck with Deirdre Jackson, Frederica Law-Turner, and Joshua O'Driscoll.