Photos of Brooklyn's Waterfront Show a Century of Change

The Brooklyn waterfront is radically changing.

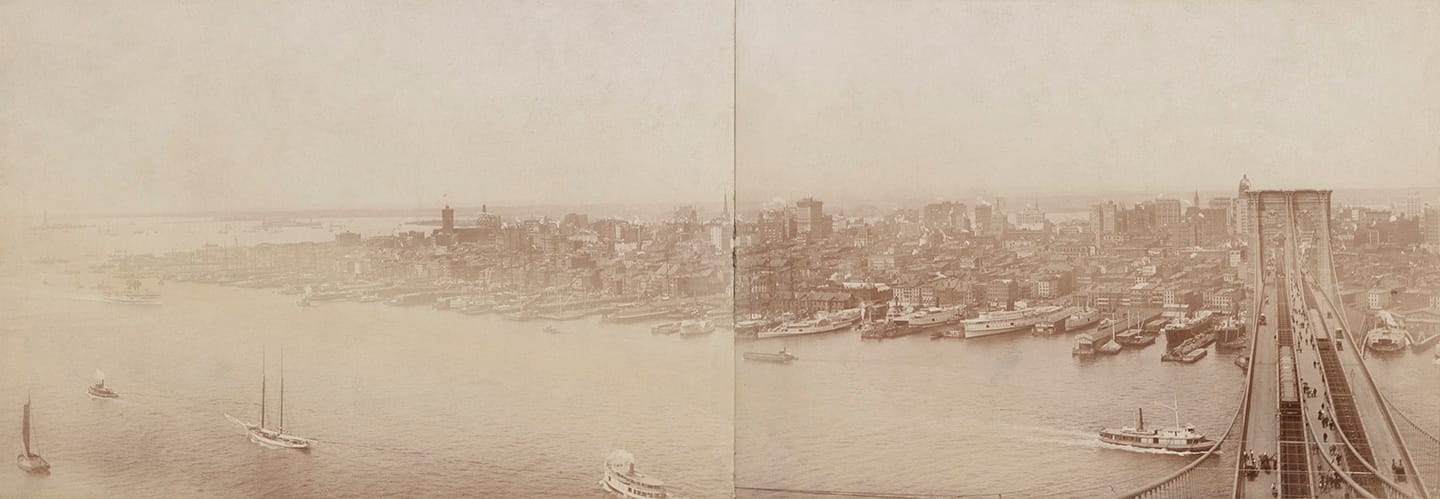

The Brooklyn waterfront is radically changing. The Domino Sugar Factory in Williamsburg is transforming into residential and commercial space, both inside its hollowed-out brick building and outside with new glassy high-rises. Towers are pending for long-quiet Greenpoint. And Brooklyn Bridge Park is altering the former industrial area of Dumbo and Brooklyn Heights with green space and, naturally, condos. It’s from the perspective of that park that the NYC Municipal Archives examined the East River shore’s long history of change.

A Century on the Brooklyn Waterfront was one of the shipping container exhibitions at Photoville, held earlier this month in the Pier 5 Uplands in Brooklyn Bridge Park. Curated by Public Records Officer Quinn Berkman and Paper and Archival Conservator Cynthia Brenwall, the exhibition drew on the NYC Municipal Archives’ 221,000 cubic feet of material, particularly its collections on the WPA Federal Writers’ and Art projects (1935–43) and the Department of Bridges (1901–39).

“The ability to appreciate what parks were before they were public recreational areas is important, and the Brooklyn Bridge Park is so relevant because the transformation is so recent,” Berkman told Hyperallergic. Many of the photographs were printed from glass plate negatives, and date from between 1870 and 1974, revealing the rise of the Brooklyn Bridge, and the concentration of maritime commercial activity on the Brooklyn piers long before they were replaced with parks.

“I think it is important to remember that Brooklyn was the heart of the city’s import business,” Berkman explained. “What is now seen as real estate opportunity was once used purely for the ports and trade industry.” It was only in the 1970s that the area was designated as a landmarked neighborhood and the repurposing of warehouses began. “It’s pretty incredible because once the Brooklyn Bridge opened, this part of Brooklyn was considered Manhattan’s first suburb, however by the 60s it cycled back into an industrial zone and now it is back to being a residential neighborhood,” she added.

The NYC Municipal Archives has recently been making more of its photographs accessible online, from the documentation of the NYPD’s “Alien Squad,” which monitored potentially subversive political groups in the 1930s and ’40s, to the around 30,000 crime photographs from 1914 to 1975 released earlier this year. As the photographs were taken for municipal government use — during the construction of the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway or the renovation of the Brooklyn Piers, for instance — some of the creators’ names are now lost. In addition to their original purposes, they now form an essential record of the city’s changing character.

“These photographs are not just ‘iconic’ images of old NYC, they are used to understand and preserve the history of the city,” Berkman said. “Photography is one of the best mediums to use to tell a story and send a message, which is also why it has just as complex of a history as New York does.”

A Century on the Brooklyn Waterfront was part of Photoville, which ran September 10–20 at the Pier 5 Uplands in Brooklyn Bridge Park (corner of Joralemon Street and Furman Street, Brooklyn Heights).