Required Reading

This week, overcharging billionaire art collectors, the recent fascination with medieval art, the world's last male white rhino, discovering the previous life of Jean-Honoré Fragonard's “Young Girl Reading,” and more.

This week, overcharging billionaire art collectors, the recent fascination with medieval art, the world’s last male white rhino, discovering the previous life of Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s “Young Girl Reading,” and more.

Russian billionaire Dmitry Rybolovlev has accused a Swiss art dealer of marking up Modigliani’s “Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu” by over $20 million:

“Which Modigliani?” Mr. Rybolovlev asked, according to people with knowledge of the conversation. Mr. Heller said it was “Nu Couché au Coussin Bleu,” one of Modigliani’s most famous nudes. Mr. Rybolovlev asked about the sale price, and the next day, after checking with Mr. Cohen, Mr. Heller told him: $93 million.

Mr. Rybolovlev was taken aback by the answer, according to people with knowledge of the matter. Mr. Heller didn’t know it, but Mr. Rybolovlev was the buyer of the painting and had paid $118 million — meaning the price had been marked up by the dealers by more than $20 million. In early January, Mr. Rybolovlev responded by filing a complaint against Yves Bouvier, a Swiss businessman and his longtime art dealer, with the General Prosecutor’s Office of Monaco alleging document forgery and fraud. Not long after, in February, Mr. Bouvier was arrested in Monaco on charges of fraud and complicity in money laundering. He is free on bail.

Some historian react to the recent fascination with conjuring up silly captions for medieval-era European illuminations:

As for some of the even more scandalous drawings, Sears explained how we shouldn’t make judgements about medieval people under our own modern-day lens.

“You know, the middle ages was very bawdy! It was before the Puritans, before the Protestant reformation. We’re just projecting Sunday school onto earlier periods,” Sears told HuffPost.

Many who owned these manuscripts were secularists, she explained, and illuminators began including more R-rated embellishments as the years went on. Like any cartoonist or comedian, being a medieval illuminator was “almost like you’re getting paid for your imagination,” Sears said.

None of the art historians HuffPost spoke to, however, seemed particularly offended by the Internet’s caption game.

“If this particular trend gets people more interested in the art of the Middle Ages, which is endlessly fascinating, then I think that’s great,” Hamburger said.

On another level, images of lynchings are frequently used as historical markers for comparative frameworks, drawing sometimes-forced comparisons with images of today’s brutalities, which often look completely different. Recently at the University of California, Berkley, an artists’ collective took it upon themselves to hang effigies of lynched Black people around the campus. Though the group meant well, according to their statement, they ended up offending many people and causing some anxiety.

Dead Black people are not ornaments to be put up and taken down for every activist need, purpose and point. Treating those who have come before us as such might reinforce our objectification and further cement our disposability in public consciousness.

A fantastic snippet of an interview with Louise Bourgeois, though the two countries have clearly changed:

In the 19th century, it was believed we could tell disease by smell. Jane Yong Kim explores the topic through the art of Anicka Yi:

The artist Anicka Yi plays with this amorphous, olfactory fear in her show “You Can Call Me F,” a meditation on contagion and femininity up through April 11 at The Kitchen. Yi’s media are bacteria and smell, and a sense of bodily invasion pervades the exhibition. She worked with cheek swabs from a hundred women—her creative peers, artists, collectors, curators, and the like—to form a bacteria collective that will grow for the duration of the show. It’s a sort of feminist ecosystem, powerful but fragile. Quarantine tents dot the dark, barren space, and the scent that permeates it is at once perfumed and antiseptic, redolent of a doctor’s office operating out of a woman’s bedroom. It’s almost pleasant, but it carries an undercurrent of danger: Where does this smell come from, exactly, and where is it going?

New research at the National Gallery of Art has discovered that Jean-Honoré Fragonard’s “Young Girl Reading” (c.1770) (left) existed as a “complete” painting, “Portrait of a Woman with a Book” (right), for at least six months before it was changed into its current form:

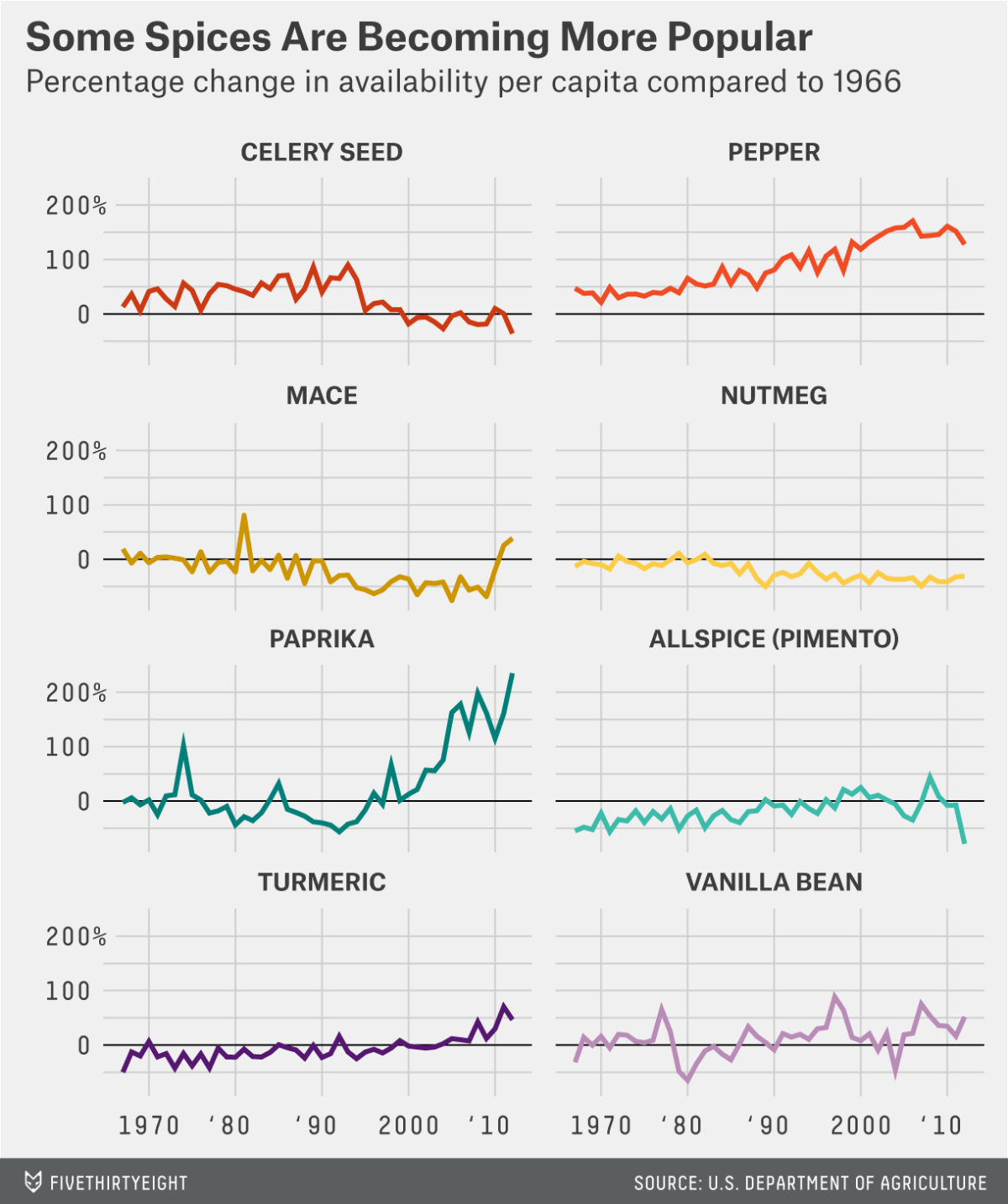

The 50-year trends of spices in US households:

An interesting interview with John Giorno, the star of Andy Warhol’s “Sleep”:

When Andy Warhol died, 1987. When a friend dies, no matter who it is, particularly right after they are dead, you think about them and remember them so clearly. I was thinking about Andy, and remembering everything like I was watching a movie. I was not a prose writer, I’m a poet, but I said to myself, “you better write about the early ’60s with Andy—25 years later—because if you wait another 25 years you are going to remember nothing.” I wrote several memoir pieces that went into my book You Got to Burn to Shine in 1994. One of the important things for me is being able to remember conversations, and create plays within the memoir. It is really funny how the mind works—no doubt it gets distorted because it is passing through my mind—but if I can remember what I said, then I can remember what the other person said next, back and forth, and it doesn’t come all at once, but over months. The dialogue shapes itself to make a point, revealing the relationship. William Burroughs was a good friend and we lived together at 222 Bowery, and I visited him often when he moved to Kansas. I started writing about him five years before he died. I wrote about August 1968, and the great moment when he came back from the democratic convention in Chicago and Kerouac was on the Buckley TV show. I wrote what I remembered being said back and forth. Then I tested it. I visited William in Kansas. We got up at 9 a.m., had breakfast—I made fried eggs and tea and we smoked joints—with the tape recorder on. I brought up ’68, Chicago, and Kerouac, setting it up. I asked the questions I remembered asking, and he answered back. William said what I remembered him saying, because he was remembering his own thoughts and words. Almost everything was the same; occasionally adjectives or constructions were slightly different. It was so close and I was very relieved.

How New York destroyed a village full of African-American landowners to create Central Park:

Two thirds of the population was black; the rest Irish. There were three churches and a school. And 50 per cent of the heads of households owned the land they lived on, a fact conveniently ignored by the media of the time, who described the population as “squatters” and the settlement as “n***er village”.

If you visited the park during its first 150 years of existence, you’d have no idea this village ever existed. It was only in 2001 that a small group called the Seneca Village Project pressured the city to install a small plaque; it describes the village as a “unique community”, which may well have been “Manhattan’s first prominent community of African American property owners”.

Since then the group, formed in the late nineties by a group of archaeologists and historians, has gone much further in bringing the village back into the cultural consciousness. In 2011, it managed to get permission to carry out an archaeological dig in Central Park, in order to find out more about the village and its residents.

The Maryland Language Science Center has created this landscape map that allows you to explore linguistic diversity around the world:

The very hilarious @TheTweetofGod account has updated the plagues:

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.