Required Reading

This week, USC's embattled dean speaks, famous artists review books, defending gallery assistants, and more.

This week, USC’s embattled dean speaks, famous artists review books, defending gallery assistants, and more.

Carolina Miranda of the LA Times spoke to Dean Erica Muhl of USC’s Roski School of Art & Design about her embattled program:

Q: Why do you think you only have one student for the fall?

A: The negative publicity may have affected recruitment efforts. But we have an incredibly strong program, and we will continue to support it. We are going to support an International Artist Fellow [a fully funded position], who will attend in the fall. We are looking to pause recruitment and then continue to recruit at a later date.

The New York Times Book Review asked five well-known artists to review a book. They are:

- Wangechi Mutu on The God of Small Things by Arundhati Roy

- Joan Jonas on Why Look at Animals? by John Berger

- Jacolby Satterwhite on Mature Themes by Andrew Durbin

- Kader Attiaon on African Art as Philosophy: Senghor, Bergson and the Idea of Negritude by Souleymane Bachir Diagne

- Ed Ruscha on Oklahoma Tough: My Father, King of the Tulsa Bootleggers by Ron Padgett

This week’s edition is also the Art Issue.

Jerry Saltz rightfully defends art-gallery attendants, saying that an ArtNews column by Hannah Ghorashi is particularly troubling in its attitude towards gallery employees:

And that’s the underlying problem: the way Ghorashi confuses the well-off gallery directors, with their revealing, standoffish policies about pricing, and their employees, who are just trying to hold down jobs. I’ve written before about the kind of hostility often directed at the people who work at the front desks of galleries.

Avshalom Halutz believes the oppression of Israeli culture starts with the occupation:

Only a few courageous artists have dared to regularly speak out against the occupation and the oppression of Palestinians. Only a few have objected to performing on the stages of communities in the territories, even when subjected to much public pressure, or have taken direct action against the occupation. Anyone who hasn’t fiercely fought the occupation shouldn’t complain when he finds himself occupied by the very same forces.

US photographer Mary Ellen Mark died May 25 at the age of 75, but one reporter at NPR decided to track down the subject of Mark’s most famous photograph, of a 9-year-old girl in a kiddie pool smoking a cigarette. Chris Benderev tried to find out what happened to her:

“When she came along and took those photos, I thought, ‘Well, hey, people will see me and this may get me the attention that I want; it may change things for me,'” Ellison says. She thought someone would see the images and come rescue her. “I had thought that that might have been the way out. But it wasn’t.”

Jacobson, the New York photographer, says Mark was not the type to give her subjects false impressions. But he says, “In any photographic encounter, the one person that always benefits and always is in a more powerful position and always knows more is the photographer.”

Some Yale bro stole (or appropriated, depending on your perspective) two female college students’ art, and this is what they did:

The realm of appropriation isn’t exclusive to men, of course: there are actually plenty of women artists that use appropriation and use it well. Penelope Umbrico uses appropriation to make a statement on absence and erasure; Sherrie Levine appropriated photos as a form of feminist hijacking. Both of these women took from a canon that commodifies people less powerful than them and made an ethical statement on gaze and power. What Prince and Arctander has done represents and perpetuates the opposite.

It’s not a coincidence that Prince and Arctander both chose women as their source material—and most recently, trans women specifically, as well as non-binary people of color. It’s methodical, and not without historical precedent. More established white artists have always happened to be interested in experiences that aren’t theirs. If art is about perspective, it’s also always about power: the production of it, the reclamation of it, and the violent reversal of that rebellion, too. So I can’t even say that what happened to our original photo is simply theft, and not art—I know it’s art. It’s just bad art, it’s lazy art, it’s art with a backbone of misogyny and it replicates the very ideology that the original photo pushed against. It reminds us that our stories are easily stolen—we’re only as visible as you let us be, within the confines of your control. We’re only rewarded when it’s through your lens—when you control the narrative.

Does this mean emoji are losing their luster? Chevy sent out a press release in emoji:

There has been a great deal of controversy surrounding the Confederate flag and its appropriate place. Many people have suggested museums as the best location, though in this piece Aleia Brown disagrees:

It is a symbol of white supremacy, and museums should acknowledge it as such. The designer for the second national flag of the Confederacy described it as a representation of the fight to “maintain the Heaven-ordained supremacy of the white man over the inferior or colored race.” The exhibit should also acknowledge the role the flag played in South Carolina’s past. The flag that’s captured national attention this week came to Columbia in 1962, as a reaction to black people fighting for and winning rights during the civil rights era.

An animated history of the Atlantic slave trade, which took place over 315 years, consisted of 20,528 voyages, and directly impacted millions of lives. Some trends:

There are a few trends worth noting. As the first European states with a major presence in the New World, Portugal and Spain dominate the opening century of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, sending hundreds of thousands of enslaved people to their holdings in Central and South America and the Caribbean. The Portuguese role doesn’t wane and increases through the 17th, 18th, and 19th centuries, as Portugal brings millions of enslaved Africans to the Americas.

In the 1700s, however, Spanish transport diminishes and is replaced (and exceeded) by British, French, Dutch, and—by the end of the century—American activity. This hundred years—from approximately 1725 to 1825—is also the high-water mark of the slave trade, as Europeans send more than 7.2 million people to forced labor, disease, and death in the New World. For a time during this period, British transport even exceeds Portugal’s.

In the final decades of the trans-Atlantic slave trade, Portugal reclaims its status as the leading slavers, sending 1.3 million people to the Western Hemisphere, and mostly to Brazil. Spain also returns as a leading nation in the slave trade, sending 400,000 to the West. The rest of the European nations, by contrast, have largely ended their roles in the trade.

By the conclusion of the trans-Atlantic slave trade at the end of the 19th century, Europeans had enslaved and transported more than 12.5 million Africans. At least 2 million, historians estimate, didn’t survive the journey.

When you fly, make sure there are no cat stowaways:

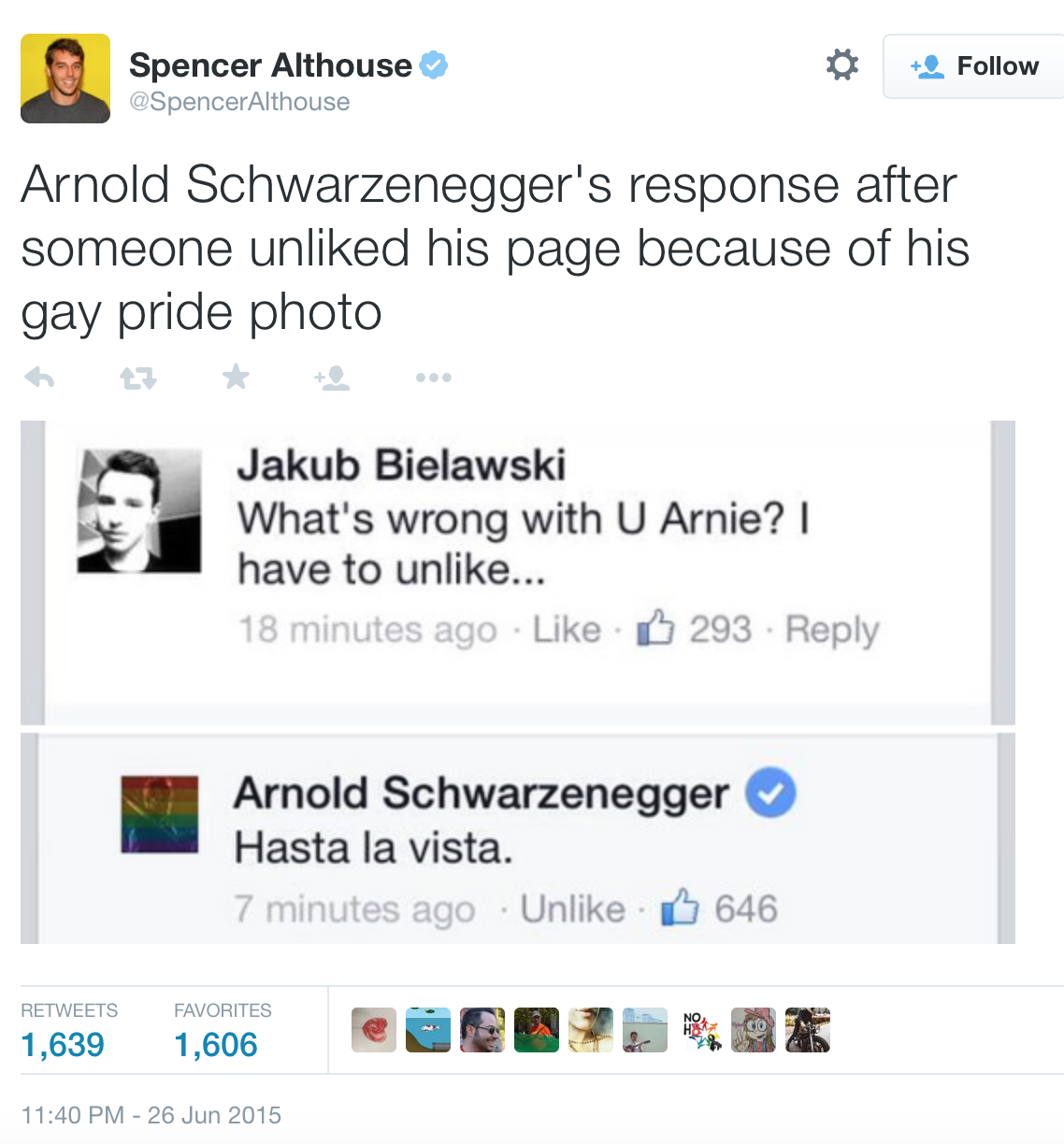

And this beautiful response by Hollywood star and former California governor Arnold Schwarzenegger:

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.