Required Reading

This week, 35 women tell their Bill Cosby stories, reflecting on memory in the internet age, how are performance artists paid, white privilege in Baltimore's music scene, and more.

This week, 35 women tell their Bill Cosby stories, reflecting on memory in the internet age, how are performance artists paid, white privilege in Baltimore’s music scene, and more.

Everyone has been talking about New York magazine’s cover story that allows 35 women to tell their own stories about being assaulted by Bill Cosby, and the “Culture That Wouldn’t Listen”:

There are now 46 women who have come forward publicly to accuse Cosby of rape or sexual assault; the 35 women here are the accusers who were willing to be photographed and interviewed by New York. The group, at present, ranges in age from early 20s to 80 and includes supermodels Beverly Johnson and Janice Dickinson alongside waitresses and Playboy bunnies and journalists and a host of women who formerly worked in show business. Many of the women say they know of others still out there who’ve chosen to remain silent.

A beautiful piece by Cathy Park Hong on Paul Celan, Doris Salcedo, and memory in the internet age:

To make art representing another victim’s pain can be ethically thorny. Susan Sontag wrote, “The appetite for pictures showing bodies in pain is as keen, almost, as the desire for ones that show bodies naked.” Images of suffering can arouse our horror, simulating an illusive identification between us and the victim or “a fantasy of witness” before we are conveniently deposited back into our lives so that someone else’s trauma becomes our personalized catharsis.

But Salcedo refuses our appetite for the sanguinary, refuses any attempt at verisimilitude because what is absent in her work is the body in pain. Tragedy has not been transmuted into a consumable narrative or embedded into an instant, catch-all image. There is a somber restraint to her artwork, a silence; these stories she’s gathered cannot be represented. Said Salcedo: “I have constructed the work as invisibility, because I regard the non-visual as representing a lack of power. To see is to have power; it’s a way of possessing.”

James Tarmy has some radical ideas on art galleries, which often lose money, and how they should make money. But first some facts:

Last year, Resch sent out an anonymous electronic survey to 8,000 galleries, and more than 16 percent, or about 1,300 people, responded with information about their revenue, number of employees, and location …

The results are grim: Fifty-five percent of the galleries in Resch’s survey stated that their revenue was less than $200,000 per year; 30 percent of the respondents actually lost money; and the average profit margin of galleries surveyed was just 6.5 percent. (Lest a critic argue that the pool was too skewed to rural galleries selling crafts, or decorative arts galleries buckling under the weight of their unsalable Louis XV chairs, 93 percent of Resch’s respondents represent contemporary art galleries.)

Including this controversial nugget:

Galleries generally split the sale of a work 50/50 with the artist. Resch argues that—given that galleries often have to cover marketing, production, shipping, and insurance costs—it should be closer to 70/30. Cue artist outrage.

How are artists paid for performance art?

They said that they learned that the going rate museums paid performers in major 2010 exhibitions was about $20 an hour, which they found low and arbitrary. (This includes Marina Abramovic’s piece at the Museum of Modern Art, they said, and Tino Sehgal’s at the Guggenheim, the first performance piece that museum acquired.)

White privilege and black lives in the Baltimore music scene:

It has at times proven difficult to talk about these things with white peers in Baltimore. I think white individuals, whether we’re musicians or not, often avoid discussions about our role in racism because we’re afraid of admitting our complicity in and collective responsibility for the centuries-long suffering of black people, let alone the horrific extent of that suffering. We may also be afraid of speaking out of turn and beyond our authority, although that may also be a lie we tell ourselves to mask the fact that we’re afraid culturally of being conspicuous. Because of that fear, white people are given to thinking about racism as society’s problem instead of a personal issue, and we don’t confront it, or at least not in the ways that would be most useful. White people need to talk about it amongst ourselves more often and in depth. We need to not just be aware of racism, but work to actively destroy it. Abdu makes a very good point regarding this necessity in Baltimore: “If people don’t get it together, come together and try to create some musical, creative community that is really diverse and multi-cultural, everybody gonna be shit-fucked by gentrification and the shade of capitalism because once money starts coming through here, they won’t give a fuck about punk shows and shit like that.”

The Seattle Review of Books just launched. Can’t wait to see what they do.

Ron Rosenbaum interviews author E.L. Doctorow for the LA Review of Books:

Doctorow is not a fan of “the social construction of reality,” the way society conditions us to see things. This may be the most radical thing about him. You don’t see it in the comfortable bookish solidity of his apartment, but he’s steeped in the discipline of epistemology, the skeptical investigation of how we know what is real, really real, and what is the product of conventional “social construction,” an illusion. It’s almost as if he’s been influenced by his late friend Peter Matthiessen, the novelist Zen teacher — who turns out to be a neighbor of his at the Doctorows’ summer place in Sagaponack.

In any case there was another moment like that one with “never the twain can meet,” when I ask Doctorow about a key incident in the new novel — the Bunsen burner incident. I had a sense that it was a kind of hidden lynchpin to the novel, one that connected Andrew’s peculiar narrative to American history in a way critics had failed to see.

When a neighborhood’s demographic shift hits the grocery store:

Having the right kind of supermarket in Alhambra isn’t about convenience, Myers said. Her complaints about grocery shopping can snowball into grievances about bad driving, rude service at restaurants, cleanliness and eventually, what kind of community Alhambra should be and what it means to be American. Conversations about grocery stores, Myers said, always become conversations about belonging.

“All the businesses and the markets are becoming Asian,” Myers said. “And I just don’t fit in here anymore.”

City leaders say they tried to negotiate to keep the Ralphs in place, but they can’t tell landlords what tenants to contract with. They have even less control over the demographics of the city, which have changed dramatically during Myers’ lifetime.

The Advanced Placement (AP) courses for US history have been whitewashed:

Passages that previously cited racial attitudes, stereotyping, and white superiority in early American history have been rewritten or deleted, and some passages that previously implicated early European colonists in racism and aiding in destructive Native American warfare have been softened and replaced with more passive language.

In 1981, news program 20/20 aired a segment on the rising phenomenon of rap music, and it’s pretty funny to watch (h/t @kottke):

… and part 2:

The story of a 56-year-old male model and photographer who is homeless in New York:

I didn’t think that I’d wind up spending the better part of six years sleeping there, but that’s what happened. Amazingly, I got away with it without ever having to tell my friend what I was doing. I was careful not to run into him on the stairs, or any of the other residents for that matter. I learned to constantly hold my cellphone in my hand so I could fend off any questions by pretending I was on the line with someone.

One of the great things about being in New York is that everyone’s too busy to notice you. I was just a middle-aged white guy who wasn’t drunk or wearing dirty clothes, so I didn’t raise suspicion.

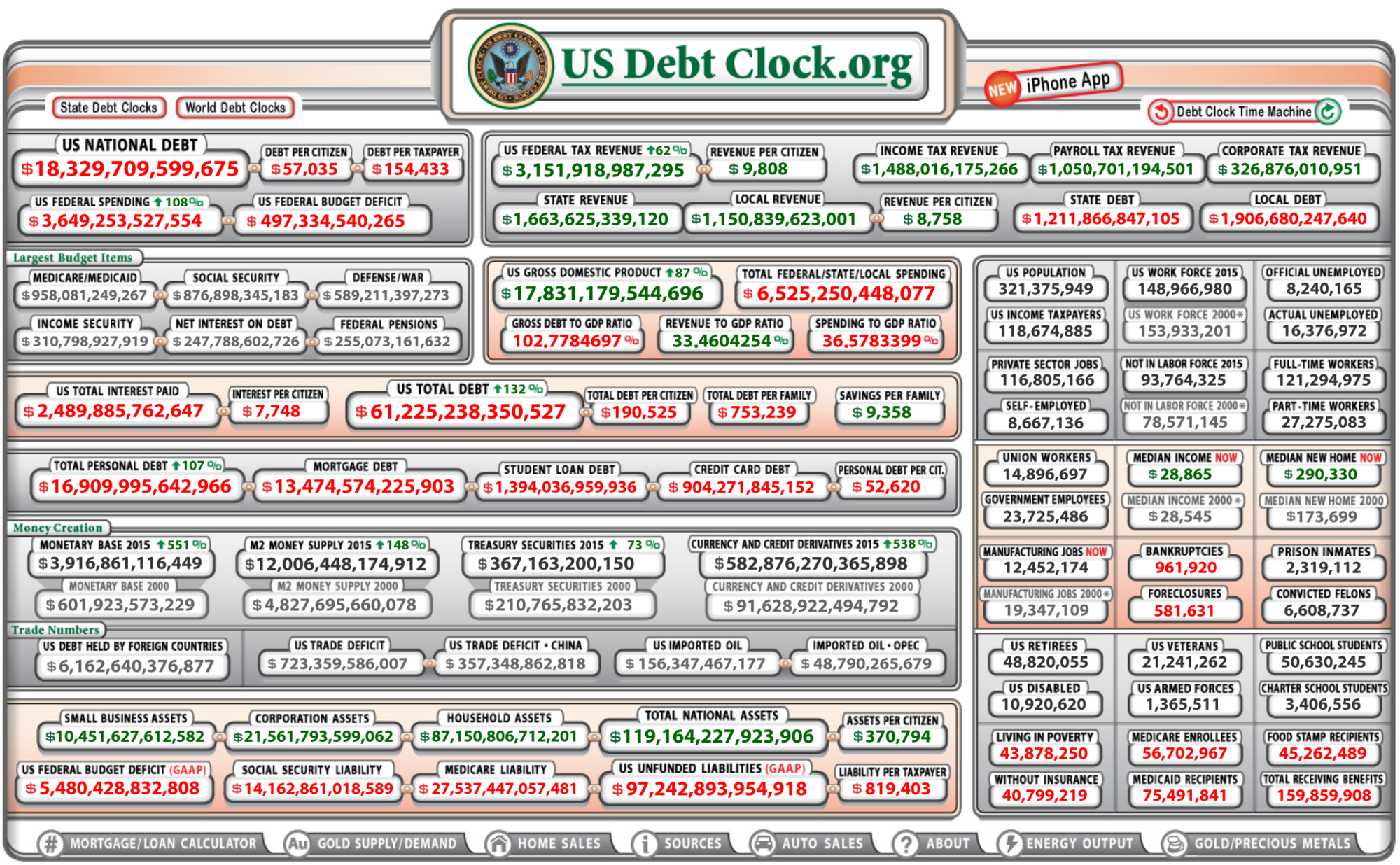

The US National Debt visualized (also the debt of nations around the world):

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.