Required Reading

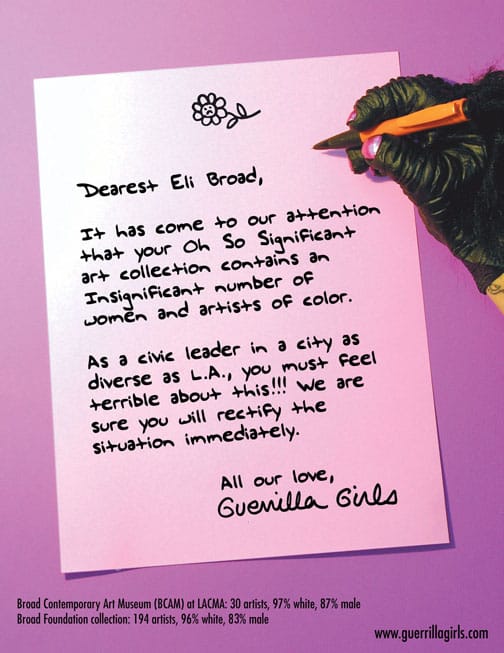

This week, did Duchamp appropriate a woman's artwork, Naomi Wolf compares Kathryn Bigelow to Leni Riefenstahl, how photojournalism is changing, Guerrilla Girls critical of Broad collection, and more.

This week, did Duchamp appropriate a woman’s artwork, Naomi Wolf compares Kathryn Bigelow to Leni Riefenstahl, how photojournalism is changing, Guerrilla Girls critical of Broad collection, and more.

A new book asks if the revolutionary “Fountain” was created by a feminist artist and later appropriated by Marcel Duchamp:

Her work was championed by Ernest Hemingway and Ezra Pound; she was an associate of artists including Man Ray and Marcel Duchamp, and those who met her did not forget her quickly. Yet the Baroness remains invisible in most accounts of the early 20th-century art world. In the eyes of most of the people she met, the way she lived and the art she produced made no sense at all. She was, perhaps, too far ahead of her time.

… But is it true to say that Fountain was Duchamp’s work? On 11 April 1917 Duchamp wrote to his sister Suzanne and said that, “One of my female friends who had adopted the pseudonym Richard Mutt sent me a porcelain urinal as a sculpture; since there was nothing indecent about it, there was no reason to reject it.” As he was already submitting the urinal under an assumed name, there does not seem to be a reason why he would lie to his sister about a “female friend”. The strongest candidate to be this friend was Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven. She was in Philadelphia at the time, and contemporary newspaper reports claimed that “Richard Mutt” was from Philadelphia.

If Fountain was Baroness Elsa’s work, then the pseudonym it used proves to be a pun. America had just entered the First World War, and Elsa was angry about both the rise in anti-German sentiment and the paucity of the New York art world’s response to the conflict. The urinal was signed “R. Mutt 1917”, and to a German eye “R. Mutt” suggests armut, meaning poverty or, in the context of the exhibition, intellectual poverty.

In a very provocative piece, Naomi Wolf compares filmmaker Kathryn Bigelow to Nazi-funded filmmaker Leni Riefenstahl because of Zero Dark Thirty and its apology for torture:

In a time of darkness in America, you are being feted by Hollywood, and hailed by major media. But to me, the path your career has now taken reminds of no one so much as that other female film pioneer who became, eventually, an apologist for evil: Leni Riefenstahl. Riefenstahl’s 1935 Triumph of the Will, which glorified Nazi military power, was a massive hit in Germany. Riefenstahl was the first female film director to be hailed worldwide.

It may seem extreme to make comparison with this other great, but profoundly compromised film-maker, but there are real echoes. When Riefenstahl began to glamorize the National Socialists, in the early 1930s, the Nazis’ worst atrocities had not yet begun; yet abusive detention camps had already been opened to house political dissidents beyond the rule of law – the equivalent of today’s Guantánamo, Bagram base, and other unnameable CIA “black sites”. And Riefenstahl was lionised by the German elites and acclaimed for her propaganda on behalf of Hitler’s regime.

But the world changed. The ugliness of what she did could not, over time, be hidden. Americans, too, will wake up and see through Zero Dark Thirty’s apologia for the regime’s standard lies that this brutality is somehow necessary. When that happens, the same community that now applauds you will recoil.

Like Riefenstahl, you are a great artist. But now you will be remembered forever as torture’s handmaiden.

RELATED: Here is the shocking Vice story on how the CIA helped produce Zero Dark Thirty.

Critic Christopher Knight considers why the Broad Foundation’s “generous” lending program may not work:

The ultimate problem is this: The hybrid concept is at cross-purposes with itself. Museums cherish permanence, while lending libraries value transience.

We live in an age of hybridization, from vehicles that run on gas and electricity to artistic genres that blur once-distinct boundaries between media, or else cross-breed art with other disciplines, including technology, philosophy, science and political action.

But some hybrids are oil and water. They don’t mix.

Sarah A. Chrisman decided to act out her Victorian fantasies by living as if it were over a hundred years ago:

Five years ago we bought a house built in 1888 in Port Townsend, Washington State — a town that prides itself on being a Victorian seaport. When we moved in, there was an electric fridge in the kitchen: We sold that as soon as we could. Now we have a period-appropriate icebox that we stock with block ice. Every evening, and sometimes twice a day during summer, I empty the melt water from the drip tray beneath its base.

Every morning I wind the mechanical clock in our parlor. Each day I write in my diary with an antique fountain pen that I fill with liquid ink using an eyedropper. My inkwell and the blotter I use to dry the ink on each page before I turn it are antiques from the 1890s; I buy my ink from a company founded in 1670. My sealing wax for personal letters comes from the same company, and my letter opener was made sometime in the late Victorian era from a taxidermied deer foot.

But many people weren’t having it, and writer Rebecca Onion has a great response:

There are many irritating things about this article. The irony of congratulating yourself on sticking to 1880s technology in a piece circulated on the Internet is an obvious place to start. The author has also published two books, and will publish a third this fall; this feat was presumably accomplished with at least some assistance from computers and the Web. Certainly the note at the bottom of the Vox article directing readers to her website provoked its share of raised eyebrows.

… The Chrismans also take a preposterously rosy view of their favorite era, choosing to recall the quaint elements of Victorian life and ignore its difficulties. Chrisman complains that people are sometimes cruel to her and her husband for their period predilections: “We live in a world that can be terribly hostile to difference of any sort. Societies are rife with bullies who attack nonconformists of any stripe.” This was true for their precious late-19th-century decades as well. Ask Ida B. Wells, driven out of Memphis in 1892 for protesting lynching, or a Chinese laborer prohibited from entering the United States under the terms of the 1882 Exclusion Act.

Even if an 1890s version of Chrisman, or of her husband, would have lived a comfortable and privileged life, they could not have lived it in a vacuum, as the 2010s Chrismans are attempting to do. The social world around them would have demanded that they take some kind of a stance on the mores and ideologies dominant at the time. Would you accept the fact that immigrant children in your town worked in a factory, or protest against it? If you’re female, would you drop your education when your family thought you’d had enough? These are choices that the sealed world of the Chrismans’ re-enactment doesn’t demand of them.

Hyperallergic Senior Editor Jillian Steinhauer’s cat essay for the Walker Art Center’s newly released book is on Longreads, and you should definitely read it:

Our relationship with animals is long, deep seated, and complex, but what seems to carry consistently across the millennia is an attitude of reverence. The ancient Egyptians venerated cats; cows are an important symbol in Hindu scripture. In critic John Berger’s telling, “Animals first entered the imagination as messengers and promises.” Think of all the folktales and fables that use animals as a path to knowledge and wisdom. (There are countless examples, from Aesop’s “The Hare and the Tortoise” and the tales of Brer Rabbit to E. B. White’s Charlotte’s Web, contemporary movies like Finding Nemo, and arguably even George Orwell’s Animal Farm.)

In the modern world, Berger says, our relationship with “animals of the mind” (as opposed to of the flesh, i.e., meat) manifests in two ways: as family and as spectacle. We keep, in other words, both our pets and our zoos (as well as our cartoon characters). In both cases, although we confine the animals, we cherish them.

The world of photojournalism is changing:

In the voluble and often swashbuckling community of photojournalists, the contest uproar pushed many questions to the fore. Who sets the boundaries of what defines photojournalism? What are industry standards when some of the techniques accepted in magazines are generally forbidden in news pages, and when such distinctions are increasingly blurred online? When technology makes it so easy to manipulate images, how much manipulation is acceptable? With viewers more sophisticated and skeptical than ever before, how can photojournalists preserve their integrity and maintain trust?

One of the best aspects of social media is how it can take people to task, like this:

These are the songs that Clear Channel advised its stations to stay away from after 9/11. They include:

- Billy Joel’s “Only The Good Die Young”

- Megadeth “Dread and the Fugitive”

- Metallica “Seek and Destroy”

- All Rage Against The Machine songs

- Nine Inch Nails “Head Like a Hole”

- Soundgarden “Blow Up the Outside World”

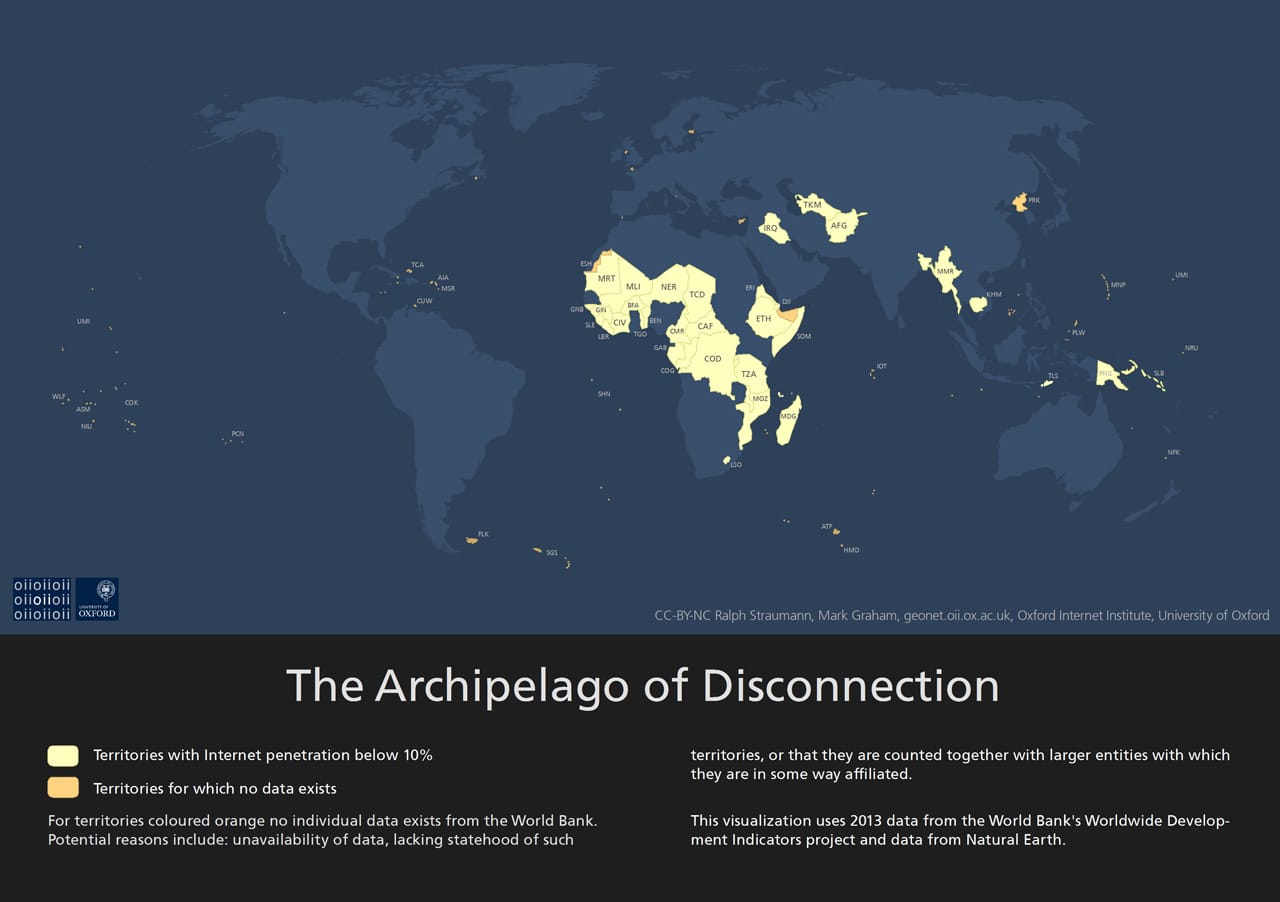

Here are the places in the world with less than 10% internet penetration:

Super Mario Brothers has turned 30, and this is how it has evolved over the years:

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.