Required Reading

This week, a white poet's yellowface, this Hirshhorn Museum's new director and new problems, Brazilian Pop art politics, the photographic politics of Instagram, 4,500 Man Ray artworks in Queens, and more.

This week, a white poet’s yellowface, this Hirshhorn Museum’s new director and new problems, Brazilian Pop art politics, the photographic politics of Instagram, 4,500 Man Ray artworks in Queens, and more.

Everyone is still talking about the Yi-Fen Chou incident in Best American Poetry 2015, where white poet Michael Derrick Hudson used an East Asian pseudonym as a “strategy” to get his poems published, and it worked. Isaac Fitzgerald of BuzzFeed was the first to point out the bizarreness. The editor of the book, Sherman Alexie, defended his decision to publish Hudson’s work even after he discovered the ruse. His explanation has upset many:

I only learned that Yi-Fen Chou was a pseudonym used by a white man after I’d already picked the poem and Hudson promptly wrote to reveal himself.

Of course, I was angry at the subterfuge and at myself for being fooled by this guy. I silently cursed him and wondered how I would deal with this colonial theft.

So I went back and reread the poem to figure out exactly how I had been fooled and to consider my potential actions and reactions. And I realized that I hadn’t been fooled by anything obvious. I’d been drawn to the poem because of its long list title (check my bibliography and you’ll see how much I love long titles) and, yes, because of the poet’s Chinese name. Of course, I am no expert on Chinese names so I’d only assumed the name was Chinese. As part of my mission to pay more attention to underrepresented poets and to writers I’d never read, I gave this particular poem a close reading. And I found it to be a compelling work. In rereading the poem, I still found it to be compelling. And most important, it didn’t contain any overt or covert Chinese influences or identity. I hadn’t been fooled by its “Chinese-ness” because it contained nothing that I recognized as being inherently Chinese or Asian. There could very well be allusions to Chinese culture that I don’t see. But there was nothing in Yi-Fen Chou’s public biography about actually being Chinese. In fact, by referencing Adam and Eve, Poseidon, the Roman Coliseum, and Jesus, I’d argue that the poem is inherently obsessed with European culture. When I first read it, I’d briefly wondered about the life story of a Chinese American poet who would be compelled to write a poem with such overt and affectionate European classical and Christian imagery, and I marveled at how interesting many of us are in our cross-cultural lives, and then I tossed the poem on the “maybe” pile that eventually became a “yes” pile.

The name was appropriated from one of Hudson’s high school classmates, who is demanding he stop using it:

Ellen Chou said that Yi-Fen Chou, a nuclear engineer in Chicago who goes by a married name, did not want to be identified or interviewed. The family, she said, wanted Mr. Hudson to immediately stop using the name, which had a “unique spelling” and had been given to her sister by their paternal grandfather.

Ms. Chou questioned Mr. Hudson’s seeming assumption that Asian-Americans have an advantage. “He seems to think we have it easy, but we don’t,” she said. “We all worked very hard to achieve our own success. I’m just appalled by his actions.”

The Asian-American Writers Workshop asked 19 writers to respond to the Hudson “yellowface” incident, including Jenna L, Bao Phi |, Craig Santos Perez, Amy King, Justine el-Khazen, and Wendy Xu. Muriel Leung wrote:

The formula for appropriation is not at all a difficult one, or as Michael Derrick Hudson has it figured, it only consists of two steps. First, strip an identity of all its history. Second, wear the hide to your convenience. Such is the case with Hudson’s publication in Best New American Poetry through the Chinese pseudonym Yi-Fen Chou. He admits there is no “artistic” reason behind his actions, only an irritating curiosity to see if wearing the identity of a Chinese writer by paper would lead to more publication success… and it has! Not by any merit of the work itself, or as co-editor of the anthology, Sherman Alexie admits, the poem lingered in the “Maybe” pile for some time before consideration of the Chinese-sounding name shifted the “Maybe” to a “Yes.” So there are multiple failures here. One is the man who dons yellowface for literary success. Another is the institution that acknowledges this appropriation and welcomes the imposter into its pages anyway.

Janu Hu published her own response at the Guardian:

White modernist poetry, as it happens, has a long history of obsessing over the Chinese. Ezra Pound wrote what he called “translations” of Chinese poetry after discovering Ernest Fenollosa’s unpublished notes on Chinese poetry and Japanese Noh drama. Pound, like all the modernists, wanted to revitalize poetry in the West. He thought that in translating these poems he was introducing new life into the form – one that did away with the overwrought sentimentality of Victorian poetry and instead took up a language that presented things directly.

Kriston Capps profiles the relatively new Hirshhorn Museum Director Melissa Chiu and how she has upset much of DC with her New York–centric ideas:

Does Melissa Chiu hate D.C.? In the words of hometown hero Bryce Harper: That’s a clown question, bro. Her protestations of Natitude notwithstanding, Chiu could be a strong friend to the District and its artists and viewers. There may be some things she doesn’t understand about the city. But there are also things that residents don’t realize about her, and in particular, about her plans for D.C.

Chiu insists she can start to put the city’s art on the art-world map by hosting the museum’s 40th birthday in New York—by dissing D.C., even if she insists that this isn’t what she’s doing.

RELATED: Chiu’s husband, Benjamin Genocchio — who is also the editor of Artnet News, did something shady and scrubbed all negative references on Chiu’s Wikipedia page, which is against the rules:

Those changes didn’t sit well with some users. Wikipedia content is user-generated, but conflicts of interest are verboten. Users reported his edits as suspect, and “bgenocchio” and a related account “1artlovernewyork” are now identified as likely being connected to the subject, and thus “strongly advised” to stop messing with it.

Photographer Joey L. is struggling with Instagram, which doesn’t like the fact that he is including images of people the US considers terrorists on his feed. It raises questions about the politics of images:

The problem, it seems, is that the images he posts depict what is considered by some to be a terrorist group. So it’s not a matter of gore or distaste, but rather a matter of politics. The deletion of the images seems to have stemmed from numerous complaints and reports from IG users, though this complaining was also accompanied by death threats and gruesome spamming of his social media accounts.

One of the photos that was taken down was put back up by Joey, in a manner of speaking. He posed with a large print of it, ironically to be displayed in the National Portrait Gallery Of London this year. Instagram, it seems, is more discerning? Maybe not.

Photographer Joey L.'s photos of Kurdish PKK fighters deleted by Instagram: http://t.co/WcDiAms4gf pic.twitter.com/zeI6te73jv

— PetaPixel (@petapixel) September 16, 2015

Is the real story of Pop art all about the Brazilians and their contributions?

In Brazil, though, pop was much more violent – and only more so as the regime’s grip tightened.

Sometimes it was less pop than agitprop. Marcello Nitsche painted a thrusting index finger – a reference to Uncle Sam in American army recruitment posters – with a huge drop of blood spilling from it. But unlike European figures who took a similarly acid view of world affairs (French artists of the time were painting Technicolor pictures of Mao and Mickey Mouse), Brazilian artists really were living in an American-backed regime, and they risked everything by speaking out. In 1968, the dictatorship promulgated the notorious Institutional Act No 5, which officialised censorship and suspended habeas corpus, paving the way to the torture chamber. The singers Caetano Veloso and Gilberto Gil were swiftly imprisoned. Numerous artists, including Dias and Maiolino, went into exile.

Pope Francis is creating a lot of buzz around his politics, which seem more progressive than any other Pope. The Nation wonders if he’s rekindling a radical economic perspective that once used to be more prominent in the Catholic Church:

For more than a century (or nearly two millennia, if you include monasticism), Catholics have been the leading developers of cooperative enterprise. The first credit union in the United States was founded by French-speaking Catholics in New Hampshire in 1908. The world’s largest network of worker cooperatives, the Mondragon Corporation in Spain’s Basque country, was founded by a priest. The US bishops’ Catholic Campaign for Human Development is among our chief funders of democratic, cooperative businesses. Around the world, Catholic Relief Services does the same.

Pope Francis credits his father, an overworked accountant, with imparting to him “a great allergy to economic things.” But from the same source he also remembers hearing, as a teenager, about the virtues of cooperativism: “It goes forward slowly,” his father said, “but it is sure.” In an address to members of Italian cooperatives last February, Francis championed what he called “an authentic, true cooperative…where capital does not have command over men, but men over capital.” In Laudato si’, he proposes cooperatives as a means of correcting our distorted relationships to technology and energy grids.

Cooperativism is neither capitalist nor communist, and the same is true of Francis. He’s a leader formed in the skirmishes between the First and Second worlds—accepting neither, and turning to Catholic tradition for older and wiser alternatives to them both. He came of age in the heyday of Peronism in Argentina, and he learned from the Peróns how to walk a kind of both-and line between a Marxist’s identification with the masses and a conservative’s savvy among the powers that be. He identified with “God’s holy faithful people,” both to needle politicians into concern for the poor and to chasten priests tempted to trade their faith for secular revolution.

RELATED: The New Yorker‘s profile of the Pontiff is worth your time:

According to Piero Schiavazzi, a journalist who has written extensively about the Vatican, “There is a struggle going on within the Vatican, between the more capitalist-minded people, like Cardinal Pell, and those who want something different. The first group is for working within the capitalist system and making as much money as possible in order to do good works. The other group, which Francis may favor, thinks the Vatican should use its money to actually change the system, to invest in poor countries directly in order to change their structure.” In July, the Pope called for a new economic order, focussed on the poor, declaring, “Let us not be afraid to say it: we want change, real change, structural change,” and decrying a system that “has imposed the mentality of profit at any price, with no concern for social exclusion or the destruction of nature.” This critique of unfettered capitalism is also at the heart of his recent encyclical “Laudato Si’,” which promotes a worldwide effort to reduce global warming: “I urgently appeal, then, for a new dialogue about how we are shaping the future of our planet. . . . Climate change is a global problem with grave implications: environmental, social, economic, political and for the distribution of goods.”

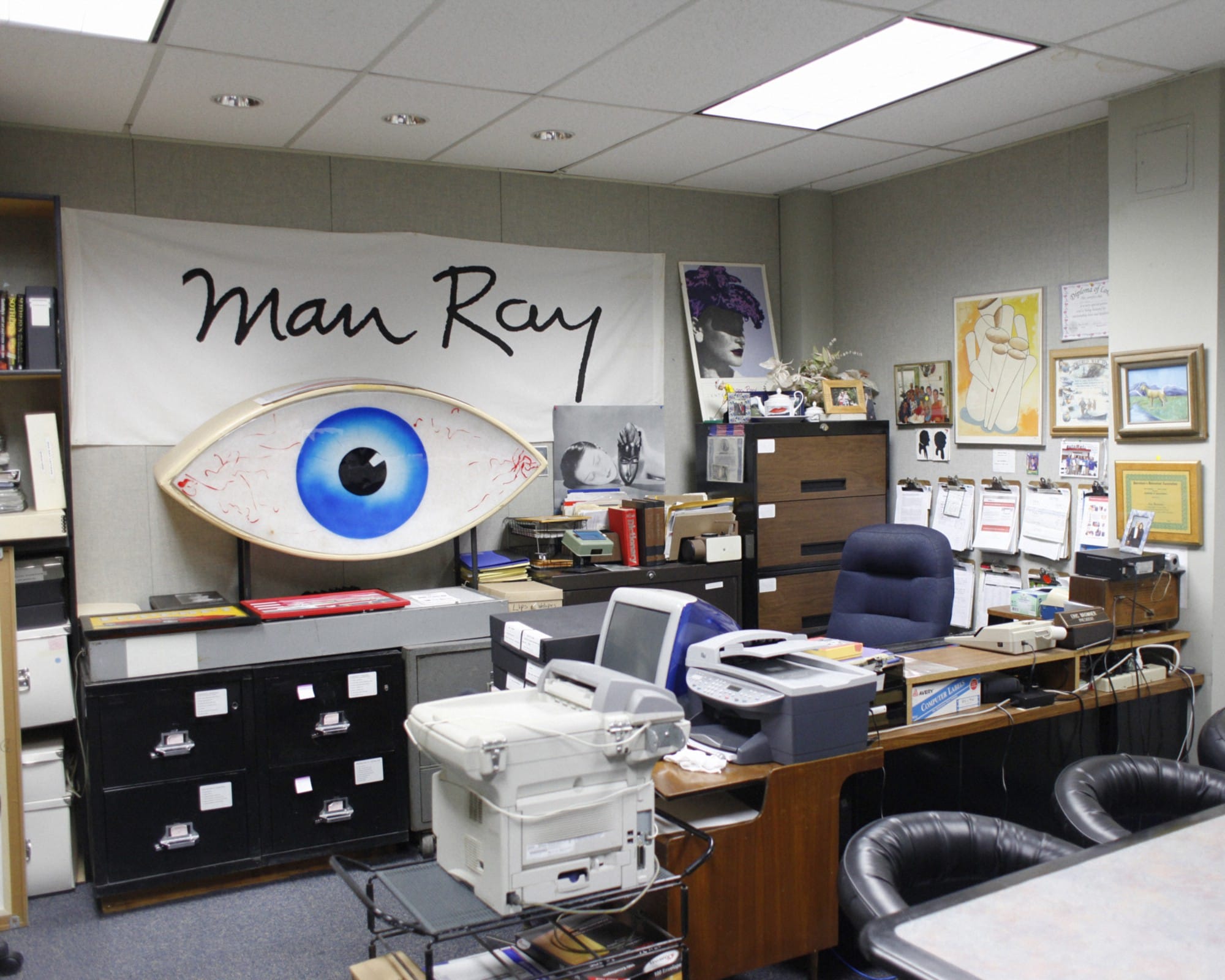

There is a huge collection of Man Ray artworks with a descendant of the artist in an auto body shop in Long Island City, Queens:

4,500 works from Man Ray’s estate and kept in 16 massive vaults. They contain many works gifted to the artist, hundreds of photographic prints, his briefcase, objects he used to make Rayographs, a metronome, etc. The story of how this collection found its home in an auto body shop is itself surreal.

11 hair experts suggest how they would fix Donald Trump’s hair:

“Part of me loves it the way it is. It’s a whole separate entity. His hair could just live by itself. His hair could be a separate candidate altogether… Would Cousin It be Cousin It without his hair? Would Don King be Don King without the fro? How could you change it?”

— Franco, Cutler Salon, SOHO

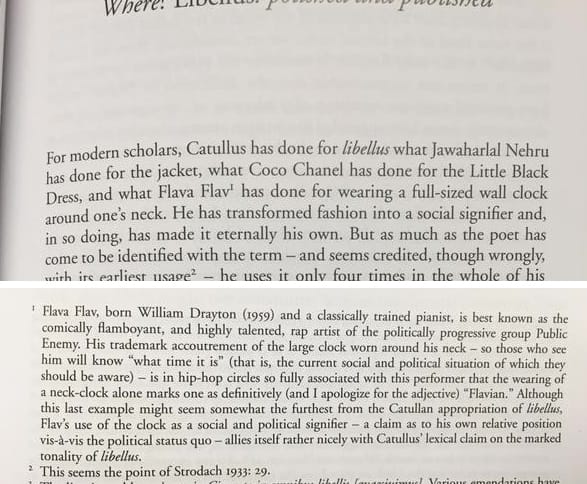

The best footnote you have read in a while (via @hashtagoras):

And the Donald:

Donald Trump just did every emoji face on your phone in 7 seconds. #GOPDebate https://t.co/jkTnY0xBp8

— Tim Williams (@realtimwilliams) September 17, 2015

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.