Required Reading

This week, goodbye, Gawker, Zombie Urbanism, Olympic medals for art, criticizing McMansions, and more.

This week, goodbye, Gawker, Zombie Urbanism, Olympic medals for art, criticizing McMansions, and more.

Gawker is closing down this week. A sad commentary on the ability for 1%-ers (in this case Peter Thiel) to silence any dissent and enact revenge on others. The mainstream media has been an accomplice in this matter by not being outraged by the matter. Former Editor-in-chief Max Read wrote an article pondering what went wrong at Gawker, if anything:

Gawker wasn’t the first publication to treat gossip as an intellectual pursuit. But it was the first to do so in the format that now seems completely natural for it: an endlessly scrolling, eternally accessible record of prattle and wit and venom that felt less like a publication than like a place. In this sense, the hook of Nick’s “barroom story” elevator pitch wasn’t the story but the barroom: a loud, sociable space for people to gossip, argue, joke, and whisper, a place where decorum and politeness were not only unnecessary but actively objectionable.

Also, yes, please save the Gawker archive!

Jonny Aspen, associate professor at the Institute of Urbanism and Landscape in Oslo, Norway, coined the term “Zombie Urbanism” in 2013 and it seems to fit today more than ever. Jeremiah’s Vanishing New York talk to him:

Q: Can you give a definition of what you call “zombie urbanism”?

A: I’ve coined the concept in order to encircle what seems to be an increasingly more prevalent, and increasingly more worrying, phenomenon in contemporary urban development, namely the cliché-like way that many developers and designers talk about and deal with urban environments in general and public areas and places more specifically.

On the one hand I use it as a reference to what seems to have developed into an increasingly more homogeneous discourse, globally speaking, on what is believed to be important features of the so-called “creative city.” It’s a discourse that highlights the importance of cultural institutions, state-of-the-art architecture, and well-designed public places.

The concepts in use remind me of what the famous German sociologist Ulrich Beck has labeled “zombie concepts,” with reference to the social sciences. They are concepts that still are very much in use, but actually no longer fit the reality they intend to describe. As such the concepts are like the living dead, they are alive in our heads and our language, but not any longer useful for making precise propositions about the reality of the city.

On the other hand I use the concept of “zombie-urbanism” as a reference to how I experience many of the urban environments that come out from such a discourse, as built environments. What we can see is a kind of staged urbanism in which there is no room for irregularity and the unexpected, a well-designed, neat, and tedious urbanism based on a simplified understanding of the urban combined with more ideal aspirations about creating “living” and “people friendly” cities. You can see it in quite many urban redevelopment projects all over the world. Other examples can be found in strategies for remaking public places and plazas, such as for instance the recent developments of Times Square in New York.

The Olympics used to give out medals for art until the middle of the 20th century, and of course art worlders were never happy with the awards:

Many art world insiders viewed the competitions with distrust. “Some people were enthusiastic about it, but quite a few were standoffish,” Stanton says. “They didn’t want to have to compete, because it might damage their own reputations.” The fact that the events had been initiated by art outsiders, rather than artists, musicians or writers—and the fact that all entries had to be sport-themed—also led many of the most prominent potential entrants to decide the competitions were not worth their time.

Roxane Gay writes about the limits of empathy and why it is hard to separate an artist from their art:

We’ve long had to face that bad men can create good art. Some people have no problem separating the creation from the creator. I am not one of those people, nor do I want to be. I recognize that people are complex and cannot be solely defined by their worst deeds, but I can no longer watch “The Cosby Show,” for example, without thinking of the numerous sexual assault accusations against Bill Cosby. Suddenly, his jokes are far less funny.

I cannot separate the art and the artist, just as I cannot separate my blackness and my continuing desire for more representation of the black experience in film from my womanhood, my feminism, my own history of sexual violence, my humanity.

Merray Gerges has some thoughts about “identity” and art:

And so it remains true in the art world that anything that comes from anyone who isn’t a white male is somehow relegated to the annals of identity politics, as if white male identity is inherently neutral—i.e. cannot be made into a genre—and therefore apolitical. The same white males who complain about the sudden proliferation of programs and funding streams for people who are not them are essentially parroting a rhetoric not dissimilar to “the immigrants are taking our jobs.”

The Sunni myth is skewing the West’s perception of the Syrian war:

Similarly, these same voices describe the Syrian government as an “Alawite regime” that rules and oppresses Sunnis. However, Sunnis are heavily represented at all levels of leadership in Assad’s government. The territory it controls at this point in the war and at all points past is majority Sunni. And the Syrian armed forces are still majority Sunni. Alawites may be overrepresented in the security forces, but all that means is that they get to die more than others. It if it is an “Alawite regime,” isn’t it odd that includes and benefits so many non-Alawites?

Sunnis not only have political power in Syria, but they also have social power, more opportunities, and a greater range of choices in life compared to other states in the region ruled by Sunni heads of state. At the heart of this negligent misapprehension of what is actually happening in the Middle East is an acceptance and mainstreaming of notions of Sunni identity propagated by the most extreme voices in the Sunni world: Saudi Arabia, al Qaeda, and the Islamic State in Iraq and the Levant (ISIL).

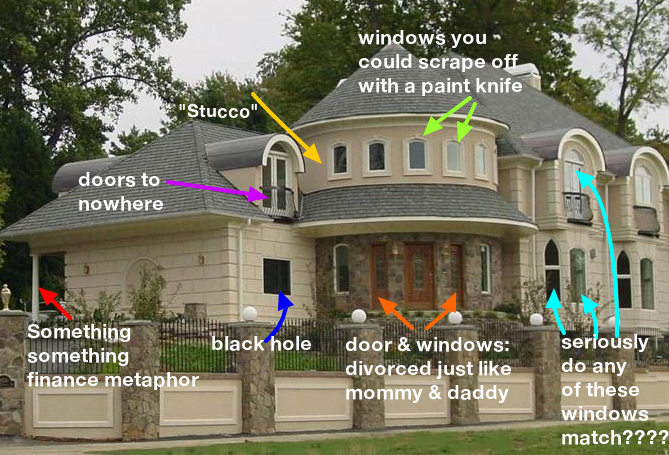

This site dissects the monstrousities that are McMansions:

How voice therapists are helping trans people find their voice:

Block, who’s been a speech therapist for 14 years, acknowledges that there can be a perception that her work with trans people is all about perpetuating gender stereotypes. Training a person’s voice to be perceived as more “masculine” or “feminine” also falls into a debate about whether it’s right to expect transgender people to conform or “pass” as either masculine or feminine, relying on male-female binaries instead of understanding gender as a spectrum.

But she says voice training is more nuanced than that: she tries to equip transgender people who come to her with vocal skills that suit their individual needs and as they transition. Rather than having a rigid understanding of what all men and all women (transgender and cisgender) ”should” sound like, she says she tries to help clients find a voice that feels right to them.

Why does the Underground Railroad figure so large in the US imagination? Maybe because it provides “white heroes”?

This lopsided awareness holds not only for institutions but for individuals. Many people know of William Lloyd Garrison, one of the country’s leading white anti-slavery activists, while almost no one knows about the black abolitionist William Still—one of the most effective operators and most important historians of the Underground Railroad, whose book about it, published a quarter of a century before Siebert’s, was based on detailed notes he kept while helping six hundred and forty-nine fugitives onward toward freedom. Likewise, more people know the name of Levi Coffin, a white Midwestern Quaker, than that of Louis Napoleon, a freeborn black abolitionist, even though both risked their lives to help thousands of fugitives to safety.

This allocation of credit is inversely proportional to the risk that white and black anti-slavery activists faced. It took courage almost everywhere in antebellum America to actively oppose slavery, and some white abolitionists paid a price. A few were killed; some died in prison; others, facing arrest or worse, fled to Canada. But these were the exceptions. Most whites faced only fines and the opprobrium of some in their community, while those who lived in anti-slavery strongholds, as many did, went about their business with near-impunity.

Black abolitionists, by contrast, always put life and liberty on the line. If caught, free blacks faced the possibility of being illegally sold into slavery, while fugitives turned agents faced potential reënslavement, torture, and murder. Harriet Tubman is rightly famous for how boldly she faced those risks: first when she fled slavery herself; then during the roughly twenty return trips she made to the South to help bring others to freedom; and, finally, during the war, when she accompanied Union forces into the Carolinas, where they disrupted supply lines and, under her direction, liberated some seven hundred and fifty slaves. By then, slaveholders in her home state of Maryland were clamoring for her capture, dead or alive, and, in the words of her first biographer, publicly debating “the different cruel devices by which she would be tortured and put to death.”

The British colonial legacy is probably worse than we realize:

Elkins emerged with a book that turned her initial thesis on its head. The British had sought to quell the Mau Mau uprising by instituting a policy of mass detention. This system – “Britain’s gulag”, as Elkins called it – had affected far more people than previously understood. She calculated that the camps had held not 80,000 detainees, as official figures stated, but between 160,000 and 320,000. She also came to understand that colonial authorities had herded Kikuyu women and children into some 800 enclosed villages dispersed across the countryside. These heavily patrolled villages – cordoned off by barbed wire, spiked trenches and watchtowers – amounted to another form of detention. In camps, villages and other outposts, the Kikuyu suffered forced labour, disease, starvation, torture, rape and murder.

Apple is dropping the word “store” from their retail outlets and people are poking fun at it:

https://twitter.com/glennf/status/766677378516914177?refsrc=email&s=11

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.