Required Reading

This week, the Facebook near-billionaire secretly funding Trump’s meme machine, Henry Louis Gates Jr. on Black American history, pocket politics, and more.

This week, the Facebook near-billionaire secretly funding Trump’s meme machine, Henry Louis Gates Jr. on Black American history, pocket politics, and more.

Jen Graves writes about an unfortunate art event in Seattle that “erased” the only two black artists participating:

Or, if you would like to make a mess like this yourself, follow these easy steps.

1. Organize an event on the topic of Erasure, and feature 40 artists, of whom only two are Black, and those two are collaborators on a single work. If you happen to notice that one of the collaborators organized a protest against the exclusion of Black artists from the exhibition Art AIDS America after being told by that curator that Black artists would have to wait for the next show in order to be seen, put this out of your mind.

2. Organize your event so loosely that nobody is really accountable or overseeing the process of installation and presentation.

…

No words. Meet Palmer Luckey … “The Facebook Near-Billionaire Secretly Funding Trump’s Meme Machine“:

Potential donors from Donald Trump’s biggest online community—Reddit’s r/The_Donald, where one of the rules is “no dissenters”—turned on the organization this weekend, refusing to believe “NimbleRichMan” was the anonymous “near-billionaire” he claimed to be and causing a rift on one of the alt-right’s most powerful organizational tools.

Luckey insists he’s just the group’s money man—a wealthy booster who thought the meddlesome idea was funny. But he is also listed as the vice president of the group on its website.

“It’s something that no campaign is going to run,” Luckey said of the proposed billboards for the project.

“I’ve got plenty of money,” Luckey added. “Money is not my issue. I thought it sounded like a real jolly good time.”

US Civil Rights veteran and Congressman John Lewis writes about the opening of the brand new National Museum of African American History:

This museum casts a light on some of the most inspiring — and uniquely American — heroes who were denied equal rights but often laid down their lives to defend this nation in every generation. Often they profited least from the struggle they were willing to die for because they believed that the promises of true democracy should belong to us all, equally and without question.

RELATED: Henry Louis Gates Jr. writes about restoring Black American history:

The connection between humanity and history was central to this debate, and in the estimation of some Enlightenment thinkers, blacks were without history and thus lacked humanity. The German philosopher Hegel argued that human beings are “human” in part because they have memory. History is written or collective memory. Written history is reliable, repeatable memory, and confers value. Without such texts, civilization cannot exist. “At this point we leave Africa,” he pontificated, “not to mention it again. For it is no historical part of the world; it has no movement or development to exhibit.”

Black people, of course, would fight back against these aspersions by writing histories about the African-American experience. In the 1880s, George Washington Williams, whom the historian John Hope Franklin called “the first serious historian of his race,” published the “History of the Negro Race in America from 1619 to 1880”; he confessed that part of his motivation was “to call the attention to the absurd charge that the Negro does not belong to the human family.”

The New York Times pulls no punches in its endorsement of Hillary Clinton:

We believe Mr. Trump to be the worst nominee put forward by a major party in modern American history.

Is a creepy company like Palantir, a Peter Thiel–founded venture, taking over New York?

A city agency, like New York’s Office of Special Enforcement, could hypothetically use Palantir’s technology for purposes that go far beyond its mandate. The agency purports to improve people’s quality of life, cracking down on building and fire code violations, for example, or identifying illegal hotels in the form of Airbnb hosts abusing the service. (Ironically, Thiel is also an investor in Airbnb.) Such investigations often lead to fines levied against property owners, and sometimes evictions.

… Just a few months later, in May 2012, Palantir submitted a statement of work and a quote for a six-month pilot program with the Financial Intelligence Center and the Department of Finance’s Audit Division. The program would identify businesses and individuals avoiding or manipulating their taxes: “Palantir engineers will integrate relevant data sets and perform search, analysis, and other investigation activities.”

The sexism and politics of pockets:

Writing for The Spectator in 2011, Paul Johnson offers a witty, thumbnail history of the sartorial convention of the pocket, and he caps his piece with a 1954 Christian Dior bon mot: “Men have pockets to keep things in, women for decoration.” Tease apart that quote and you get a fairly essentialist view of gender roles as they play out in clothing. Men’s dress is designed for utility; women’s dress is designed for beauty. It’s not a giant leap to see how pockets, or the lack thereof, reinforce sexist ideas of gender. Men are busy doing things; women are busy being looked at. Who needs pockets?

This analysis of Western dress goes down pretty easy — maybe a little too easy. It’s not to say that pocket sexism isn’t true. It is to say that pockets are more than sexist: they’re political. One way to look at the transfiguration of women’s tied-on, capacious pockets of the mid-eighteenth century into the early nineteenth century’s tiny, hand-held reticule is to consider that this transformation occurred as the French Revolution, a time that violently challenged established notions of property, privacy, and propriety. Women’s pockets were private spaces they carried into the public with increasing freedom, and during a revolutionary time, this freedom was very, very frightening. The less women could carry, the less freedom they had. Take away pockets happily hidden under garments, and you limit women’s ability to navigate public spaces, to carry seditious (or merely amorous) writing, or to travel unaccompanied.

Facebook’s photo policies are kind of irrational and look something like this:

The rules for nakedness seem to be something like this:

Not naked: OK.

Naked: bad – remove (NB male nipples OK, female nipples not OK).

Naked child: ultra-mega-very-bad – remove. No exceptions

Naked child in important news story: still ultra-mega-very-bad – remove.

Naked child in important news story now being re-posted and protested by thousands of people: still ultra-mega-very-bad – remove.

Context: irrelevant – ignore.

Protests by non-Facebookian humans: irrelevant – ignore

Protests by human non-American Prime Ministers: irrelevant – ignore.

How our latest midcentury modern design obsession reflects our age of environmental anxiety:

The connections between the resurgence of plants and our moment of environmental reckoning are palpable enough that they have become a subject for younger artists. Artist Zoe Crosher created a piece for the Los Angeles Nomadic Division in 2015 that depicts, in a series of billboards along the I-10 from Palm Springs to Los Angeles, a profusion of tropical foliage in various stages of health and decay. “There is definitely something ‘end times’ about the growing interest in plants in art and design,” Crosher says, suggesting that the profusion of plants has become a medium to contain and express our anxieties about environmental disaster.

Most immediately, Crosher says, “plants are healthy, they clean the air,” which has clear appeal in a time when pollution increasingly stresses the urban environment and global warming is making weather patterns go awry. In Mexico City, for example, the Vertical Greenway project has been encircling freeway columns with vines as a direct air-scrubbing measure.

Love this piece, which points out that minorities in Western Asia and North Africa are always erased in the Western media. Khaled Beydoun writes about Academy Award–winner Rami Malek:

However, Arab-American jubilation for the historic victory was subsequently complicated by the particular dimensions of Malek’s ethnic identity, and specifically, how his status as a Coptic Egyptian – an Orthodox Christian population indigenous to the northeastern African nation – conflicted with widespread identifications of Malek as Arab.

Ironically, the off-screen identity of Mr Robot’s Elliot Alderson – a white anti-hero cyber-security hacker – spawned a robust conversation about the intricacies and complexity of Arab identity, and related identities flatly illustrated and understood as Arab.

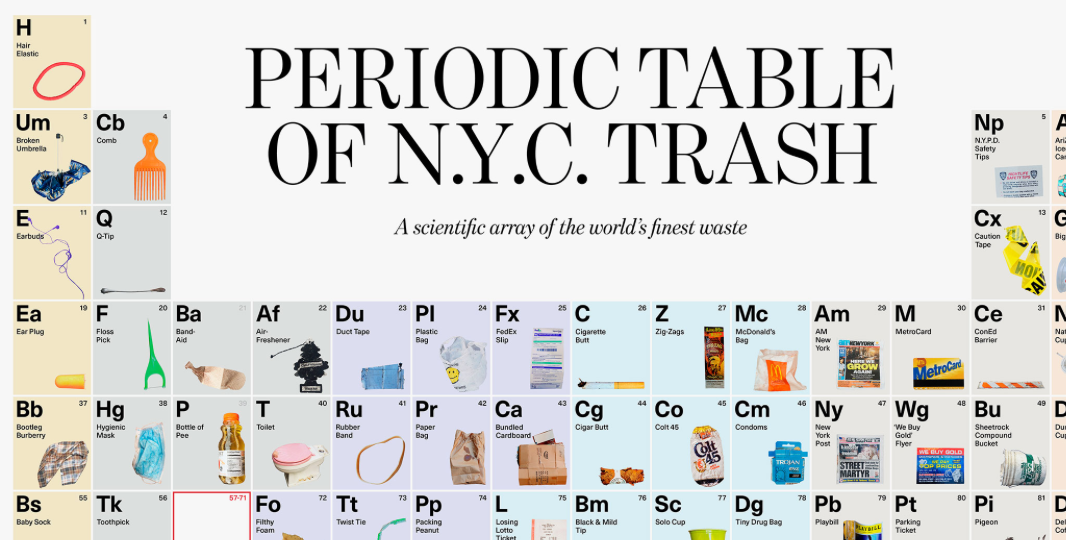

The periodic table of New York trash is quite funny:

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.