Required Reading

This week, Hollywood's drug war, commodifying Banksy, don't trust Facebook, Trump's fear of architecture critics, picturing the migrant crisis, and more.

This week, Hollywood’s drug war, commodifying Banksy, don’t trust Facebook, Trump’s fear of architecture critics, picturing the migrant crisis, and more.

Caille Milner writes about “Hollywood’s Drug War” and points out what is so very “American” about it:

Some parts of this story are now reflected in Hollywood. That the drug war affects people who aren’t American, for instance, is now understood: Narcos is not only the story of U.S Drug Enforcement Administration agent Steve Murphy’s hunt to bring Escobar down, but also the saga of Pablo Escobar’s transformation into Colombia’s top drug lord. Colombia — with its lush forests, spectacular colonial cities, resourceful and family-oriented people — is a central character in Narcos. We are allowed to feel sorrow as we watch narcotrafficking rip this beautiful country apart, and to feel conflicted the American drug cop is shown killing innocent civilians, endangering his fellow agents, and tampering with evidence. The war on drugs can taint even the good guys, Narcosreminds us; even a white man can break bad.

But this is also the problem: the “good guys” are still the American cops. We know this because Murphy tells us so. “The bad guys need to get lucky every time,” Murphy drawls in voice-over during the first season, in his West Virginia twang. “The good guys just need to get lucky once.” In the second season, we find Murphy’s can-do spirit undimmed: “We represented America down here,” Murphy says in the first episode. “We thought of ourselves as the guys who could get shit done.”

In response to a new exhibition in Melbourne, Allison Young writes about the commodification of Banksy:

The Art of Banksy is the direct consequence of his successful negotiation of the dividing line between the street and the art business. Indeed, the show exhibits works owned by private collectors, including Banksy’s former business manager Steve Lazarides, proprietor of the Lazarides gallery in London – famous both for his long association with Banksy and their very public estrangement.

… Exhibiting Banksy in Melbourne is also rife with contradictions. Banksy is much loved by Australia’s street art community, many of whom fondly remember his visit here. His remaining works in the city are regarded as endangered – gradually fading as the years go by, and also at risk from council cleaning crews and construction workers.

This archivist is imploring you not to trust Facebook with your content:

The letter, which is worth a full read, explains that Facebook is a key venue for citizens to share accounts and videos of police brutality they have suffered or seen. The letter expresses concern that the tech company will set an ominous precedent whereby it dances to whatever tune of censorship police departments orchestrate. The letter concludes its critique of this erasure within the larger Movement for Black Lives and calls on Zuckerberg to add action behind his public support of the Movement with the addition of an anti-censorship policy.

Facebook’s ultimate decision on the creation of such a policy is a moot point. Gaines was violently erased as her young son watched and was wounded. All of this took place moments after her social media presence was similarly vanquished. No policy will rectify those two facts, and given a similar situation in the future, we have no evidence to suggest Facebook will act any differently, regardless of its stated policy.

Jen Graves calls out the Henry Art Gallery in Seattle for “falling asleep” in 2016. She writes:

Let’s not forget that the Henry is the museum of the University of Washington, the largest institution of learning in our city and the one where, presumably, students from across the state and nation will, having received zero art history in public schools, get their first exposure to contemporary art.

The Henry’s PR will tell you that the Close exhibition is a first—”the first comprehensive survey of the photographic work by renowned American artist Chuck Close (b. 1940), featuring over ninety photographic works from 1964 to the present. For this showing at the Henry, we are thrilled to include a selection of objects from local collections including key paintings, works on paper, and tapestry related to the photographs.”

I trust that our neurons will have recovered from the “thrill” by the 90th example.

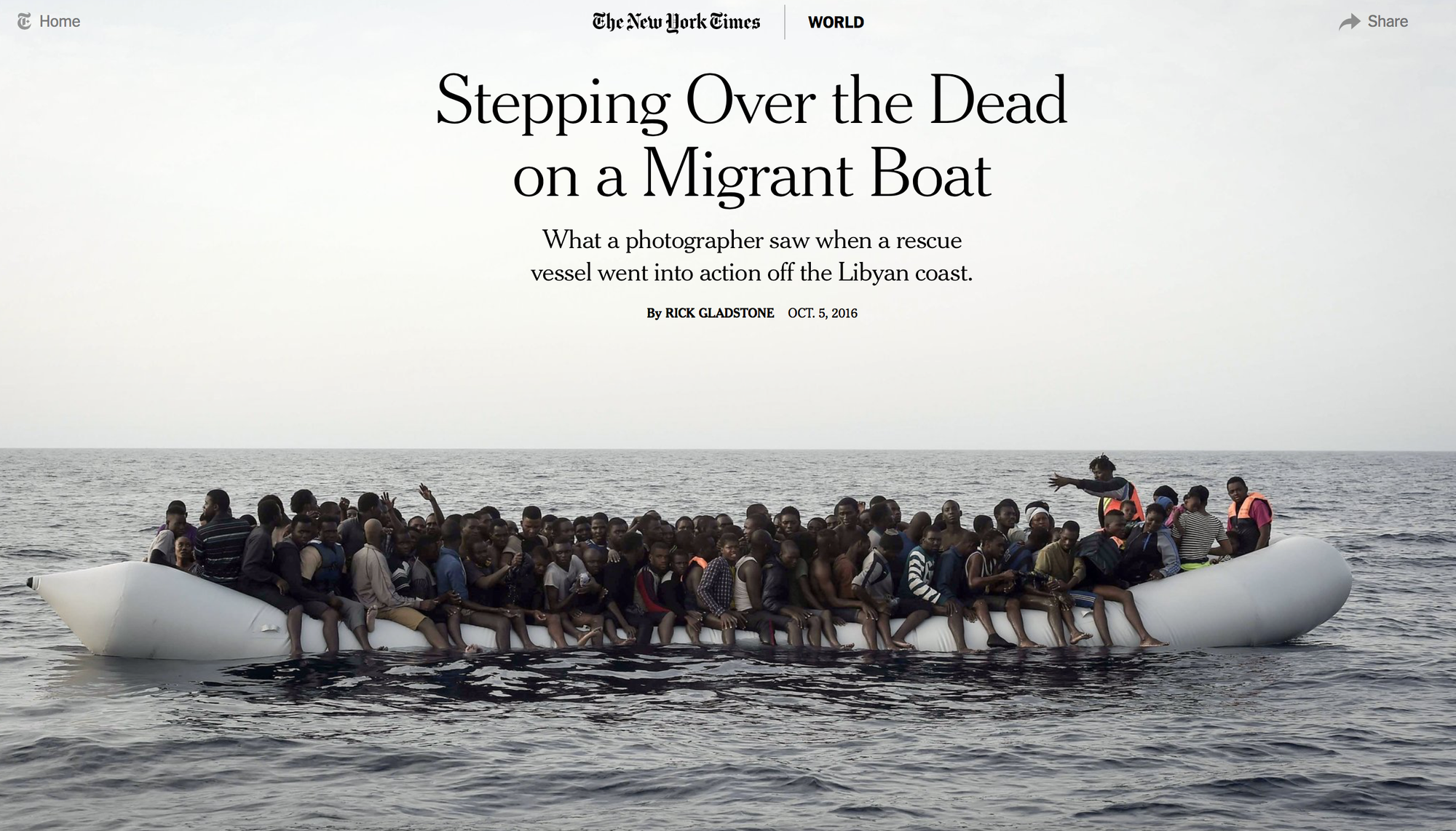

This is a shocking (and excellent) photo essay about the migrant crisis in the Mediterranean:

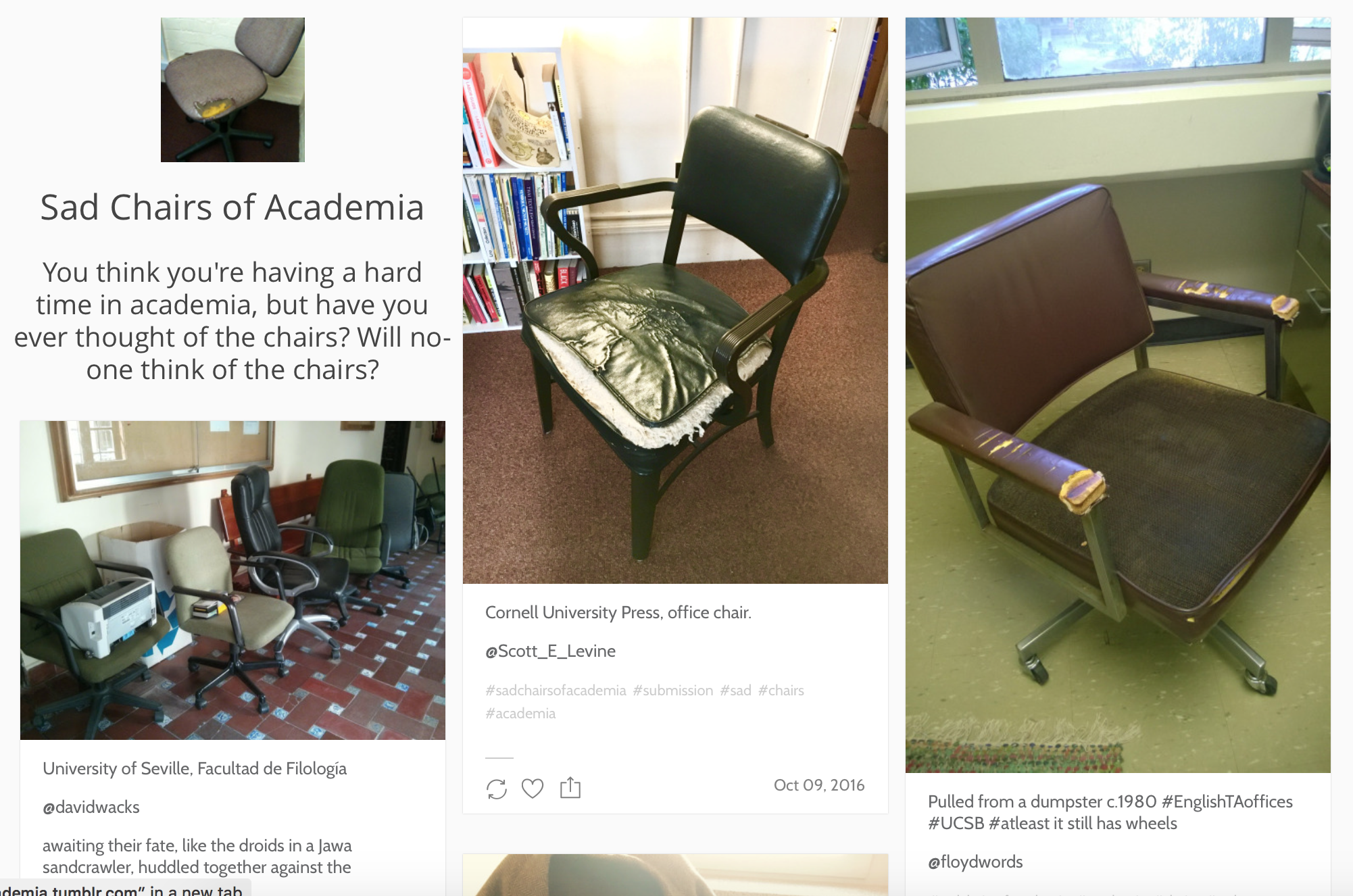

This is unfortunate interior design choice:

Alyssa Walker asks the question: “Why is Donald Trump so afraid of architecture critics?” She writes:

When you build some of the biggest (and gaudiest) buildings in U.S. cities, it’s inevitable that your work will eventually be addressed by the design critics in those cities. A great piece in Places Journal looks back at how Trump’s projects were received by legendary critics like Herbert Muschamp and Ada Louise Huxtable. (Spoiler: Not very well; Huxtable called the atrium of Trump Tower a “pink marble maelstrom.”)

So good:

Greeks created philosophy. Arabs revived it. Germans reified it. The English instrumentalized it and the French televised it.

— Karl Sharro (@KarlreMarks) October 6, 2016

Here’s the presentation hedge fund billionaire Paul Singer is using to sway the Samsung family dynasty. Singer “thinks the cell phone maker is undervalued by almost every measure — price-to-book value, price-to-earnings, what have you. And so he thinks a demerger from the parent is in order.” Check out the PowerPoint to see the language and aesthetics of high-level corporate communications.

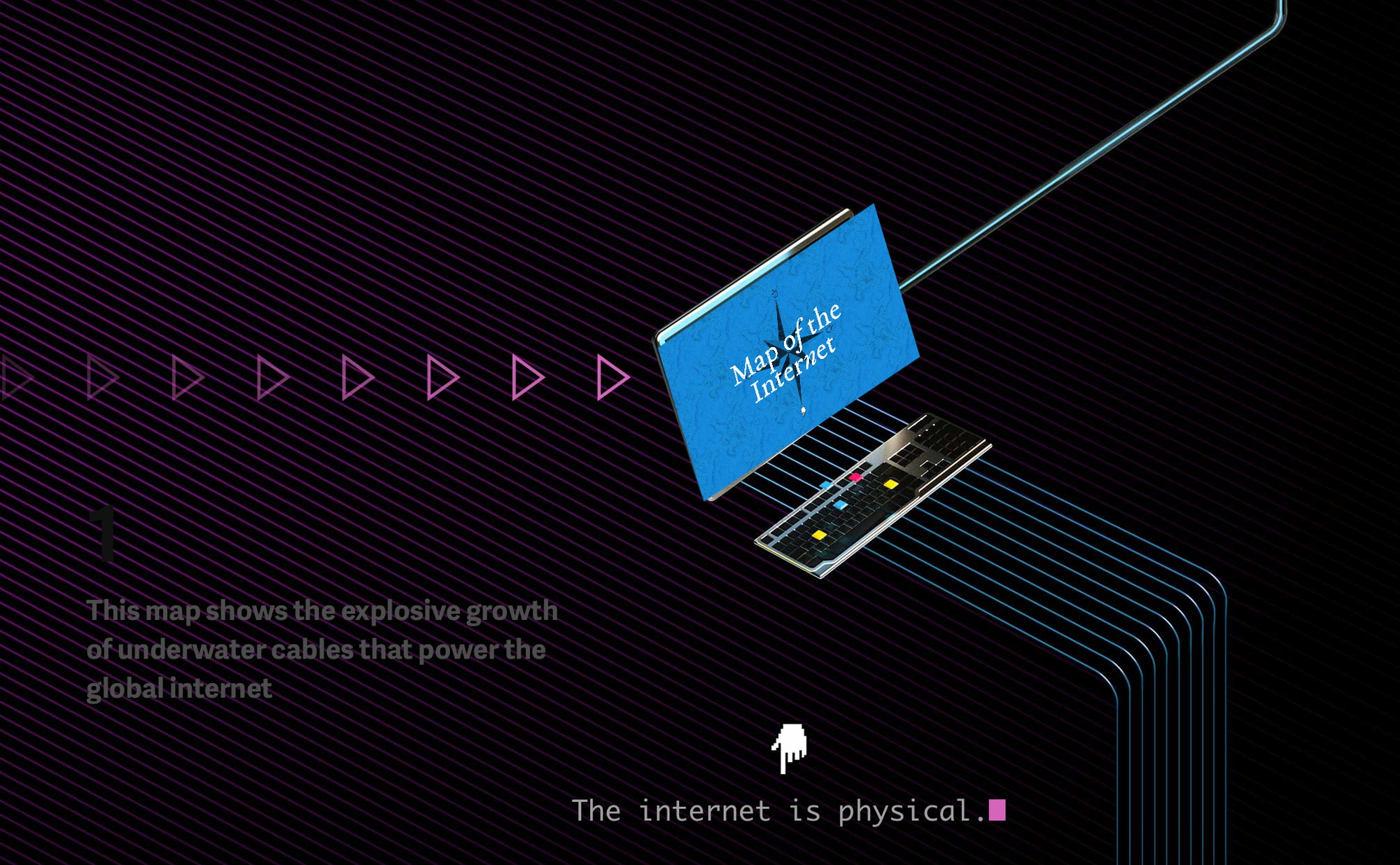

Quartz’s new series on the cables, wires, and machines that connect the world is beautifully designed (try the navigation):

There’s a metaphor in here somewhere:

Required Reading is published every Sunday morning ET, and is comprised of a short list of art-related links to long-form articles, videos, blog posts, or photo essays worth a second look.