For the Love of Constructivist Russia

The Tony Shafrazi Gallery is currently showing a rare collection of 95 rare Soviet Constructivist film posters, circa 1920-33, and a model of Vladimir Tatlin's influential "Monument for the Third International" (1920/1967). These gems of early 20th C. graphic design were cutting edge for their time

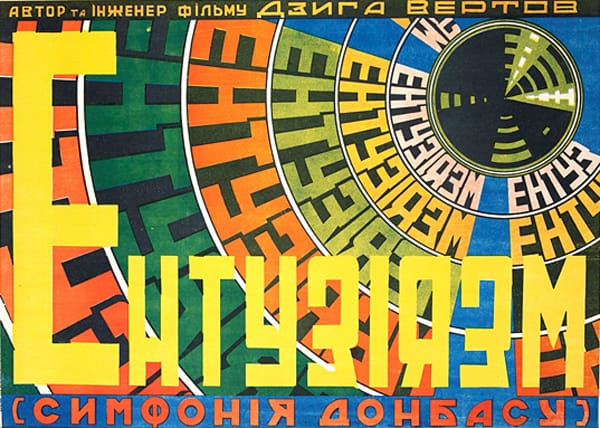

Chelsea’s Tony Shafrazi Gallery is currently showing a fantastic collection of 95 rare Soviet Constructivist film posters, circa 1920-33, and a model of Vladimir Tatlin’s influential “Monument for the Third International” (1920, reconstructed 1967).

These gems of early 20th C. graphic design were cutting edge for their time and they still look fantastic today. The visual imagination of the designers synched up quite well with the heady films during an era when the Soviet Union was still a major center of cinematic production and innovation.

What you will see at the Shafrazi gallery is the power of the Soviet avant-garde. They are brash, colorful and filled with youthful energy. Unlike the European or American posters of the era, which grew out of the work of Jules Chéret, Pierre Bonnard and Henri de Toulouse Lautrec in the 1890s and Art Nouveau, the Russians and Soviets were more influenced by book illustration and the Futurist Manifesto of 1909.

Poster art for the Soviets was considered an effective medium to broadcast the message of the revolutionary government. In their 1974 book, Revolutionary Soviet Film Posters, Mildred Constantine and Alan Fern observe:

Just as the Soviet Union had skipped over the various historical stages that might have been expected in its social structure, so the poster art which began to develop skipped over the succession of artistic styles found in western Europe. From having few posters, and not very interesting ones, the Soviet production became one of the most fascinating in the world.

Compared to the Hollywood posters of the same period, the Soviet works look like fine works of contemporary art. The work by masters of the medium, like the Stenberg Brothers, vibrate off the wall. Many of the posters on display are for foreign films, like American features with Buster Keaton, and all of them are easy to enjoy without having to be able to understand what they say in Cyrillic.

As an added bonus, the Shafrazi Gallery also has what is considered the most authentic model of Tatlin’s tower. A symbol of the inflated ambition of the Soviet Union, Tatlin’s plan was never realized because of the lack of funds, materials and leadership.

Looking back at these powerful works from an empire that no longer exists, you can’t but help but we aware that the promise of a thoroughly modern and visionary Soviet world was never realized. Soon after the period featured in this exhibition, the Soviet Union, under the leadership of Joseph Stalin, adapted Social Realism as its dominant style and threw the experiments of their avant-garde into museums (or sold them to the West). Perhaps it’s reassuring to be reminded that the capitalist or democratic worlds don’t have a monopoly on falling short of their ideals and promise.

Revolutionary Film Posters: Aesthetic Experiments of Constructivist Russia, 1920-33 and Vladimir Tatlin: Project of the Monument for the Third International Soviet Congress continue at the Tony Shafrazi Gallery (544 West 26th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) until July 30, 2011.

Homepage images is a detail of Leonid A. Voronov and Evstafiev’s poster for “October” (1927). (via tonyshafrazigallery.com)