Running Is Resistance in “Remaining Native”

The new documentary follows a Paiute teenager as he navigates his passion for running and the story of his great-grandfather, who escaped from an Indigenous residential school.

Amid the parade frenzy and triggered smoke alarms of Thanksgiving Day in New York City, a new Haudenosaunee-led documentary cuts through the noise by recentering Indigenous storytelling and resistance. Remaining Native (2025) follows Paiute teenager Kutoven "Ku" Stevens, whose goal to run professionally proves to be inseparable from the story of his great-grandfather, who ran away from a residential school for Indigenous children.

Four years in the making, Mohawk/Oneida director and producer Paige Bethmann’s film made its award-winning premiere at South by Southwest Film and TV Festival last March before embarking on its international festival circuit. The documentary's team organized a week of screenings from Friday, November 21, through Thursday, November 27, at DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema in Tribeca as part of the nationwide Fall of Freedom programming.

Remaining Native is set on the Yerington Paiute Reservation in rural western Nevada, the ancestral lands where Stevens and his parents live. At 17 years old, Stevens wants only one thing: to shave seconds off his run time so he can get recruited to the University of Oregon's renowned track and field team. Stevens, while naturally talented, is coached only by his father and ultimately left to his own devices to stand out at races.

“He was just really set on being the best runner ever,” Bethmann explained in a call with Hyperallergic.

“But with that level of commitment comes sacrifice, right?” she continued, referring to Stevens’s tunnel-vision goal that came before everything else — including his identity.

Every day, Stevens runs independently on the gravel paths in the desert land where he and his ancestors have resided for generations. His training schedule leaves him with little time to fully engage with his culture and community. But when he runs, he reaches a meditative state that allows him to reach through history and connect with his late paternal great-grandfather, Frank Quinn.

Like hundreds of thousands of Indigenous children across the colonized North American territories, Quinn had been abducted and forcibly taken to a government-funded residential training school run by Christian missionaries. From the early 19th to mid-20th centuries, the United States had over 400 boarding schools across 37 states; Quinn ended up at Stewart Indian School in Carson City, Nevada.

Formed under the assimilationist mandate to “kill the Indian, save the man,” these state-sponsored residential schools forcibly immersed abducted Native children in the cultural and religious norms of a Christian, Anglo-American population. Missionaries cut off the children’s traditionally long hair, replaced their given names with Biblical or Western ones, and inflicted vicious corporal punishment if they didn't speak in English. Family separation, forced labor, physical and sexual abuse, uninhabitable conditions, and rampant disease broke the spirits of thousands of Indigenous children — many died or took their own lives, and were buried in unmarked graves at the schools. Others, like Quinn, were able to run away.

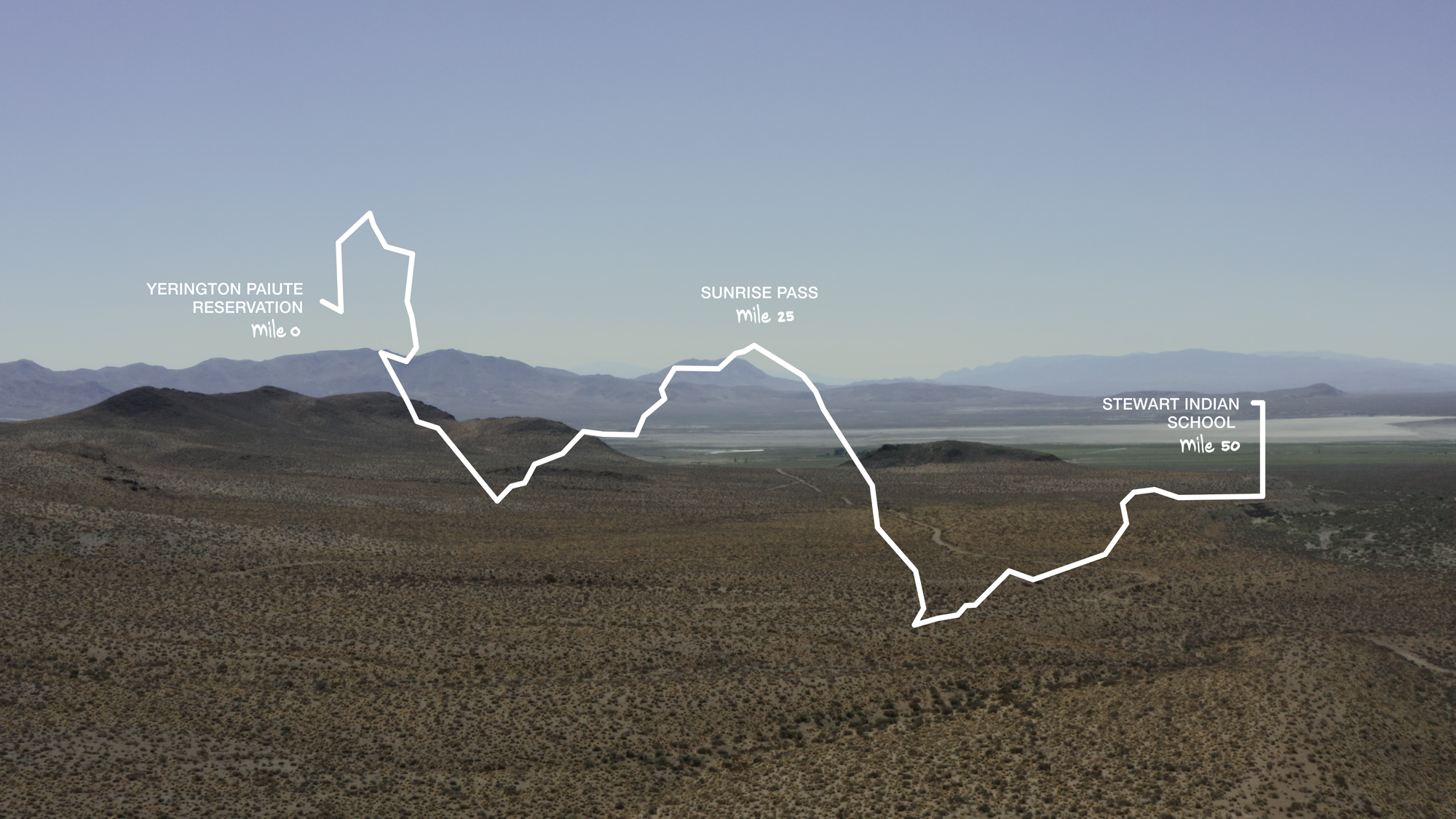

It took Quinn three tries to escape Stewart Indian School. At eight years old, he managed to run 50 miles (~80.5 kilometers) from Carson City back to his family on Paiute land in Yerington, where he spent the rest of his life and later became a respected tribal elder. In Remaining Native, Bethmann incorporates archival photographs of uniformed children at the Stewart Indian School around 1910, when Quinn would have been a student, and juxtaposes them with footage of Stevens as a young boy engaging with Paiute traditions.

“Imagine you’re eight,” Stevens’s voice repeats throughout the film as he recalls his great-grandfather’s monumental journey, acknowledging that without Quinn’s bravery and sacrifice, he wouldn’t be training for college recruitment. Stevens grapples with the weight of this legacy, even noting that his first name, which means “the eagle bringing the light from the darkness,” comes with responsibility.

In 2021, when investigators discovered hundreds of children buried at an unmarked cemetery at a Canadian residential school, further investigations throughout North America found that the Indigenous boarding school system carried a collective death toll well into the thousands.

These discoveries were profoundly traumatizing for Indigenous communities in both Canada and the United States. The Stevens family coped with the news by creating the Remembrance Run. They planned to cover the same 50 miles Quinn ran from Carson City to Yerington in a two-day run in order to channel his strength, carry his pain, and start healing through acknowledging generational trauma. Stevens has staged the annual group run three times now; Bethmann, whose own family has been similarly impacted by residential schools, filmed the run from Yerington back to the Stewart Indian School for inclusion in Remaining Native.

“The first run we did from the school to the reservation was for raising awareness, but this one in the film was about getting answers,” Stevens, now age 21, explained in a phone call to Hyperallergic. “It was about bringing this unhealed wound to the government. So we invited then-Governor Sisolak and the Nevada Senators, showed them that there's a grave site at this school, and asked them, ‘What are you guys doing about this?’”

For Stevens, remediation through the state “looks like education.”

“It looks like enforcing the history of my people being taught at a public education level because it's not accurately represented when you think of the Native American in a typical history book,” he reiterated.

Bethmann explained that she kept the government officials’ voices out of the film because “they felt empty.” She switched out their pre-written speeches with footage of the Remembrance Run's Native participants unpacking the ways in which residential schools have impacted their families.

Bethmann credits the cohort of Indigenous filmmakers at the 4th World Media Lab for their guidance and grounding, which ultimately influenced the film's narrative structure.

“They helped me honor my original intention in the way I wanted to tell Ku’s story,” Bethmann said. “It doesn't need to be linear, it doesn't need to be investigative or follow a three-act structure, it can be more aligned with our ways of storytelling.”

Remaining Native will screen three times on Thanksgiving Day at DCTV’s Firehouse Cinema.