The 2025 California Biennial Is Trapped in the Past

The show's displays of juvenilia from established artists say little about adolescents today and make its message inscrutable.

COSTA MESA, California — As a former teenage suburbanite, I arrived at the UC Irvine Langson Orange County Museum of Art’s California Biennial, Desperate, Scared, But Social, with excitement. I expected to feel kinship with the theme, which revolves around adolescence and the feelings, identity, and sense of the world that mature from it. Instead, I was underwhelmed by its shallow curiosity about today’s teenagers, and the exhibition’s stunted growth.

The biennial, which had been on hiatus for a number of years, returned with 12 artists depicting youth culture primarily through photography, painting, drawing, and readymade objects pulled from their personal archives. It also features two shows within the show — the delightful Piece of Me, organized by the Orange County Young Curators program, which gives local teens a taste of art curation and administration, and a ho-hum display devoted to pieces from the historic Gardena High School Art Collection (1919–56), a trove of early 20th century paintings that students hand-picked for their school’s investment.

The exhibition starts strong, with a presentation of Deanna Templeton’s What She Said (2000–ongoing) portrait series, accented with hot pink. The photographer pairs diary entries from her teenage years, which unfolded during the 1980s, with contemporary portraits of teen girls in countercultural movements spread throughout the world. The punks, surfers, and other subcultural groups stand out through their fashion choices, like two-toned hair, shredded tights, and safety pins doubling as nose piercings.

Most of the women, captured in a combination of black and white and color film, contrast today’s mainstream obsession with Botox and fillers to conceal the effects of aging; the alternative crowd has bags under their eyes and forehead wrinkles paired with scowls, hinting at a potentially rough life. Templeton’s diaries, on the other hand, depict the low-stakes drama of a typical high schooler. She logs concerts, talks about “fuck’n cute” boys, and summarizes petty arguments with her dad. The juxtaposition between the subjects’ appearance and the frivolous journaling suggests that these extremes aren’t mutually exclusive and collapses the teenage girl’s mythos into a universal experience.

Another intriguing entry is Heesoo Kwon’s photographic installations, which enhance childhood photographs by adding matriarchal aliens and AI-generated edits. Kwon enlarges old photographs of family moments in the kitchen or living room, sometimes stretching them to the full height of the gallery walls. The edges of these photos warp into an uncanny perspective and eventually blur into blackness, which is the work of Adobe Firefly, an AI software.

The largest image in the installation “Leymusoom Firefly, 2024, Irwon-dong, kitchen, 1990-1993” (2025) portrays the back of a child’s head in the foreground and their hand, drenched in the camera’s flash, reaching out to a woman washing something in the sink. The older woman looks over her shoulder, surprised by the camera. The digital expansion, which includes extra ceiling space, white walls, and a strange black mass that might be a mutated Christmas tree, gives the scene a haunting quality. AI’s awkward additions put the entire photograph’s authenticity in question, but that isn’t unlike memory, which can also be faulty and inventive, breaking stride with reality.

The series also opens a portal into Leymusoom, Kwon’s invented religion and hagiography, which inserts maternal ancestors into the artist’s memories. In another photo from the same installation, one of Leymusoom’s reptilian elders appears next to a woman carrying a dirty dish. Kwon has turned the photograph into a lenticular print, so the alien is only visible from certain angles, blurring boundaries between the spirit and earthly realms.

While these two artists stood out, they were exceptions. More often, the biennial made statements about adolescence through archival materials. As a result of this odd decision, many established artists presented pieces that they created in their teenage years. Laura Owens, Joey Terrell, and the 1990s riot grrrr band Emily’s Sassy Lime (Emily Ryan, Amy Yao, and Wendy Yao) — whose album Desperate, Scared, But Social (1995) gave the biennial its title — are mostly defined by their childhood relics.

Owen’s, “Untitled” (1987), made when she was a teenager, is an awkward composition of school lockers, stairs, and trash cans, stretched onto a trapezoidal canvas. The work itself doesn’t inspire deep thoughts, but its existence got me to ruminate on the childhood home my parents sold in 2018, when they finally decided to divorce. My dad was ruthless about downsizing and wanted to throw away all my drawings from high school. I had to justify their sentimental value, and rescued a few of them. Those drawings, as well as my entire childhood, were crammed into a single plastic tote that lives in my dad’s garage in Chicago.

It seems that Owens was able to salvage much more from her youth, as were Ryan and the Yao sisters. In the gallery devoted to Emily’s Sassy Lime, all three bandmates use their personal tchotchkes to recreate bookshelves from their '90s-era teenage bedrooms. A plush Garfield toy sits atop handwritten notes embellished with stickers, an ancient can of Cheez Balls, and tons of pins made by punks and zinesters. The bookcases are fun and fascinating, but simply putting nostalgia on display does little to transform its meaning or to connect past generations to today’s teenagers.

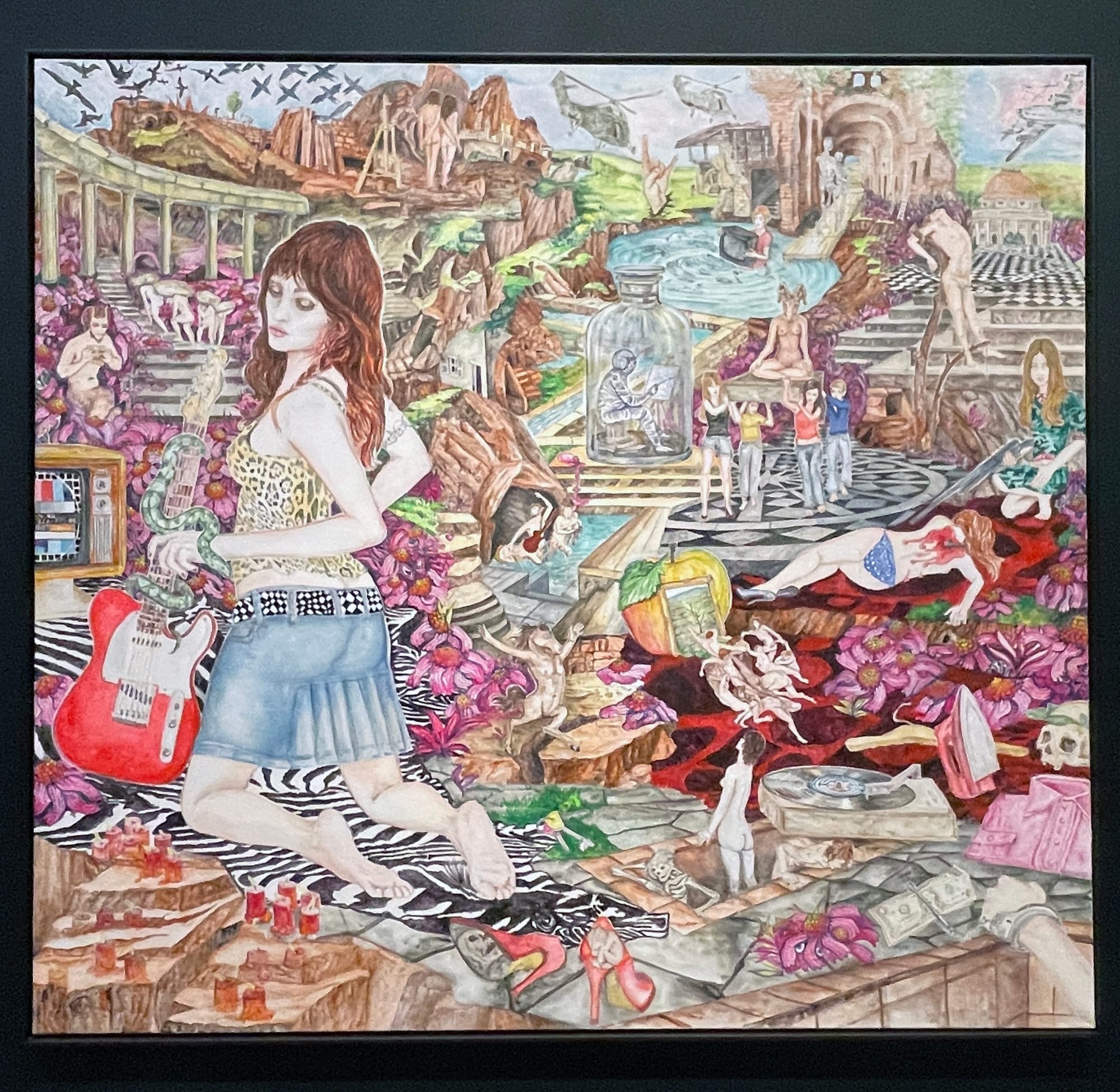

The most conceptual takes appear in the Orange County Young Curators mini exhibition, Piece of Me, which explores authenticity in the digital age. Though the curators had to work with OCMA’s permanent collection, they could still get into a teen’s mind. A dazzling painting by Abetz & Drescher, “Long Before Rock ‘n’ Roll” (2006), shows a young woman with an electric guitar posing amid a surrealist archeological site, surrounded by vignettes of sin and suffering. It’s both the trauma that has shaped her and the inner turmoil in her angsty mind. Another photographic series, Ed Templeton’s Teenage Smokers (1999), touches upon the performative acts teenagers engage in to appear cool. A modern take on this series wouldn’t even need to reshoot it with vapes, because Gen Z brought smoking back into style.

Displaying juvenilia from established artists feels like a lazy way to add some name recognition to the biennial, but says little about adolescents today and makes the show’s message inscrutable. With little remixing, Desperate, Scared, But Social’s broad strokes paint a portrait of youth that mirrors an after school special more than the real world.

The 2025 California Biennial: Desperate, Scared, But Social continues at the UC Irvine Langson Orange County Museum of Art (3333 Avenue of the Arts, Costa Mesa, California) through January 4, 2026. The biennial was organized by Courtenay Finn and Christopher Y. Lew, with Associate Curator Lauren Leving.