The African Diaspora Pictures Itself

A new exhibition rejects Western colonialism as a framework for understanding African aesthetic production.

Walking through Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination at the Museum of Modern Art, I noticed that the exhibition didn’t have definite sections or texts, and the wall labels abstained from naming the nationalities of the photographers. It was an invigorating experience to be in a show that eschews geographic boundaries set up by Western nations, as well as rejects a cause-and-effect narrative that centers Western colonialism as a framework for understanding African aesthetic production.

Here, portraiture spurs agency through reimagination, physical activations, and direct address of their audience. The exhibition presents photographers from the West and Central African diaspora dating from the mid-century to the present. Its title comes from V. Y. Mudimbe’s book The Idea of Africa (1994), which grapples with the Western theoretical constructions of the African continent. Curator Dr. Oluremi C. Onabanjo builds on the scholar's ideas by positioning portrait photography within the African diaspora as a multi-faceted, dynamic experience that fosters Pan-African subjectivity and solidarity across geography and time.

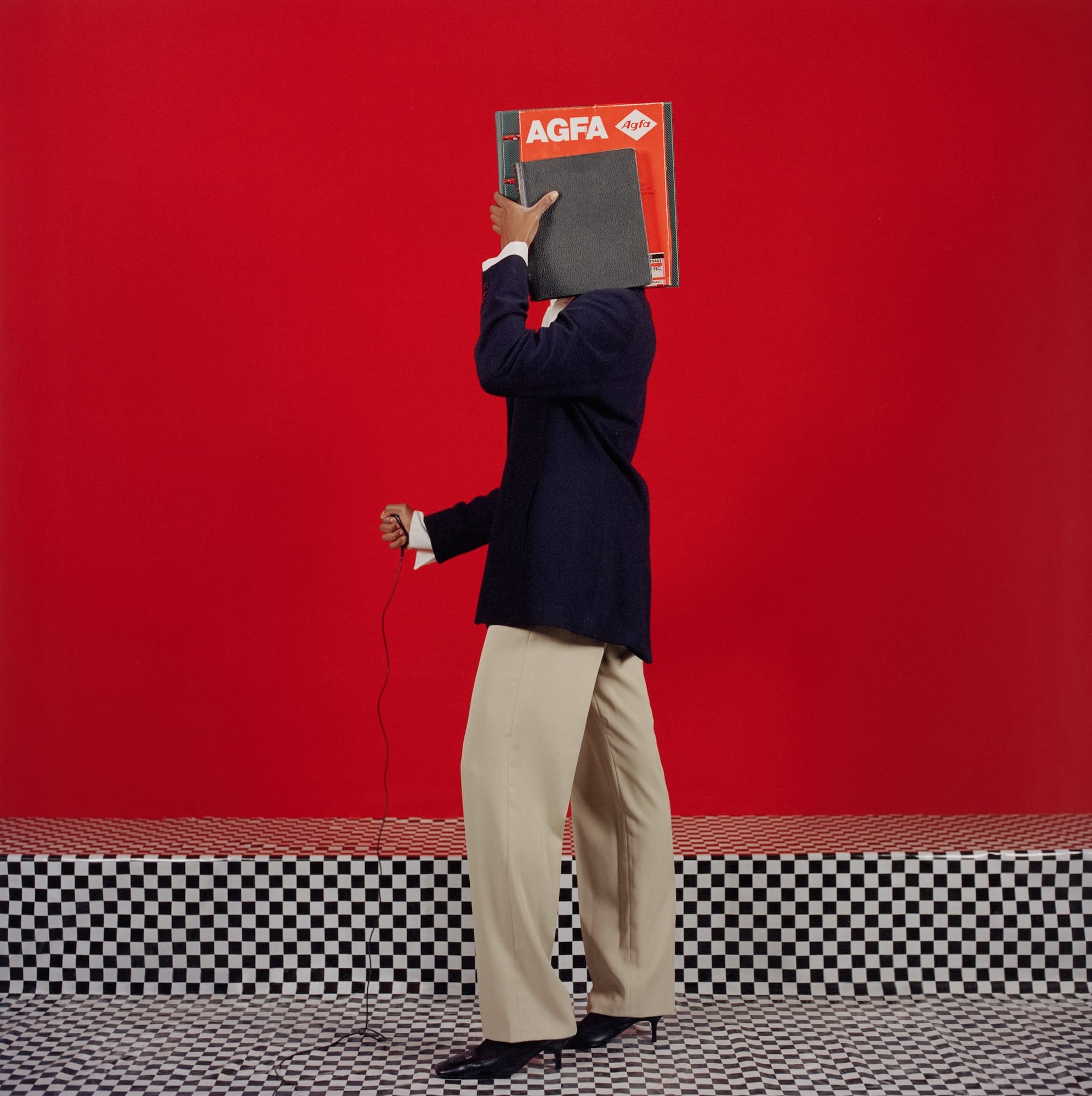

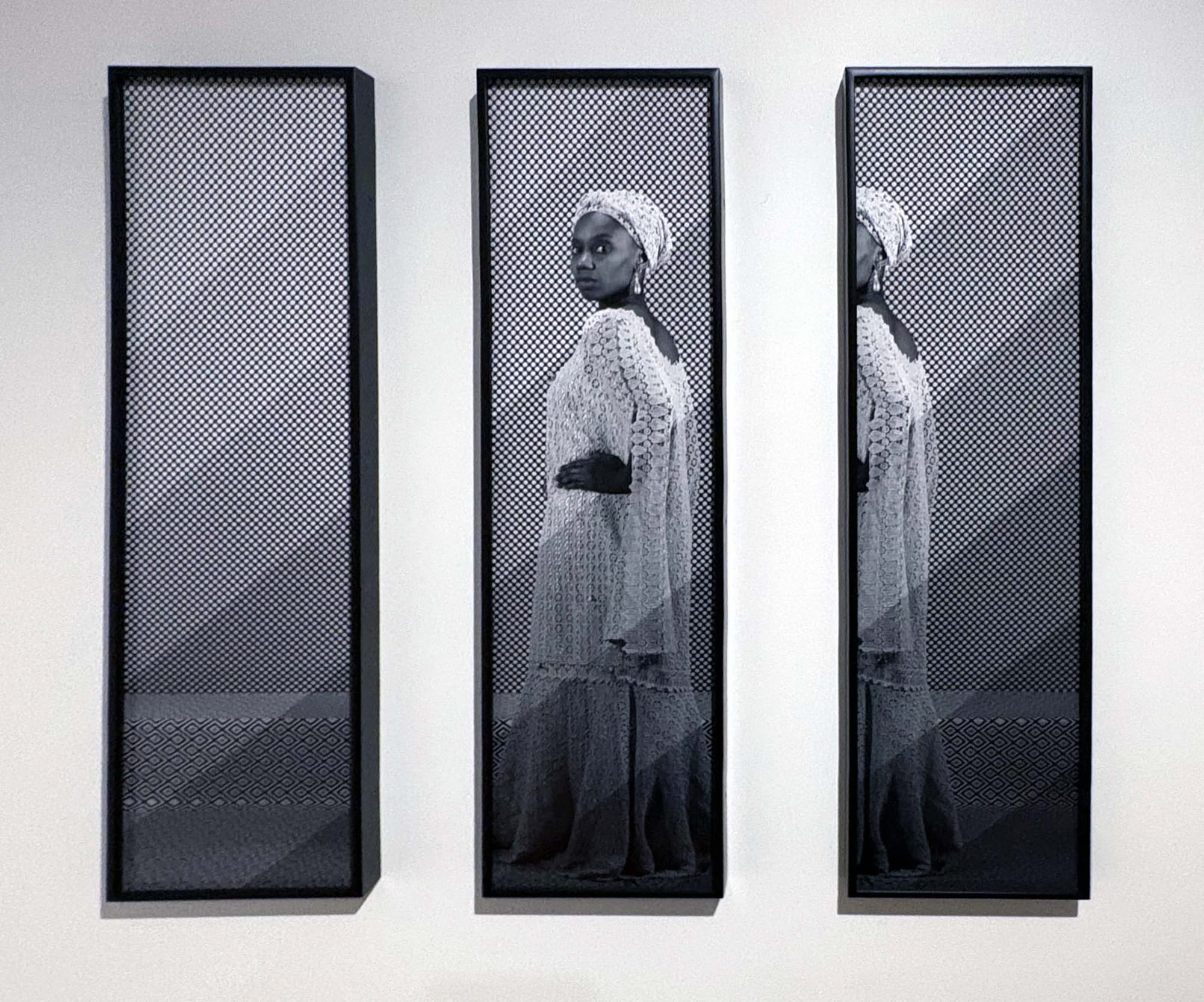

One of the first photographs a visitor encounters is a broken triptych self-portrait by contemporary photographer Silvia Rosi entitled “Sposa togolese disintegrata (Disintegrated Togolese Wife)” (2024). Rosi is known for producing self-portraits in which she captures herself holding the shutter release. In her early works, she often depicts herself as either her mother or father to produce a “reimagined” family album that referenced her Togolese heritage and her family's migration to Italy. Later photographs, such as this one, continue this reimagining of memory, mobility, and personal history by depicting a fractured and fading grayscale image of a Togolese wife.

As with Rosi’s prominent placement of the shutter release, other portraits center physical activation as a mode of aesthetic agency across the African diaspora. Photographs by renowned portrait photographer Seydou Keïta include one of a woman leaning on a radio, another woman leisurely reclining, and loved ones holding or leaning on each other. In photographs by Ambroise Ngaimoko, we see a young man clutching his arm, two people holding hands, and a couple holding each other.

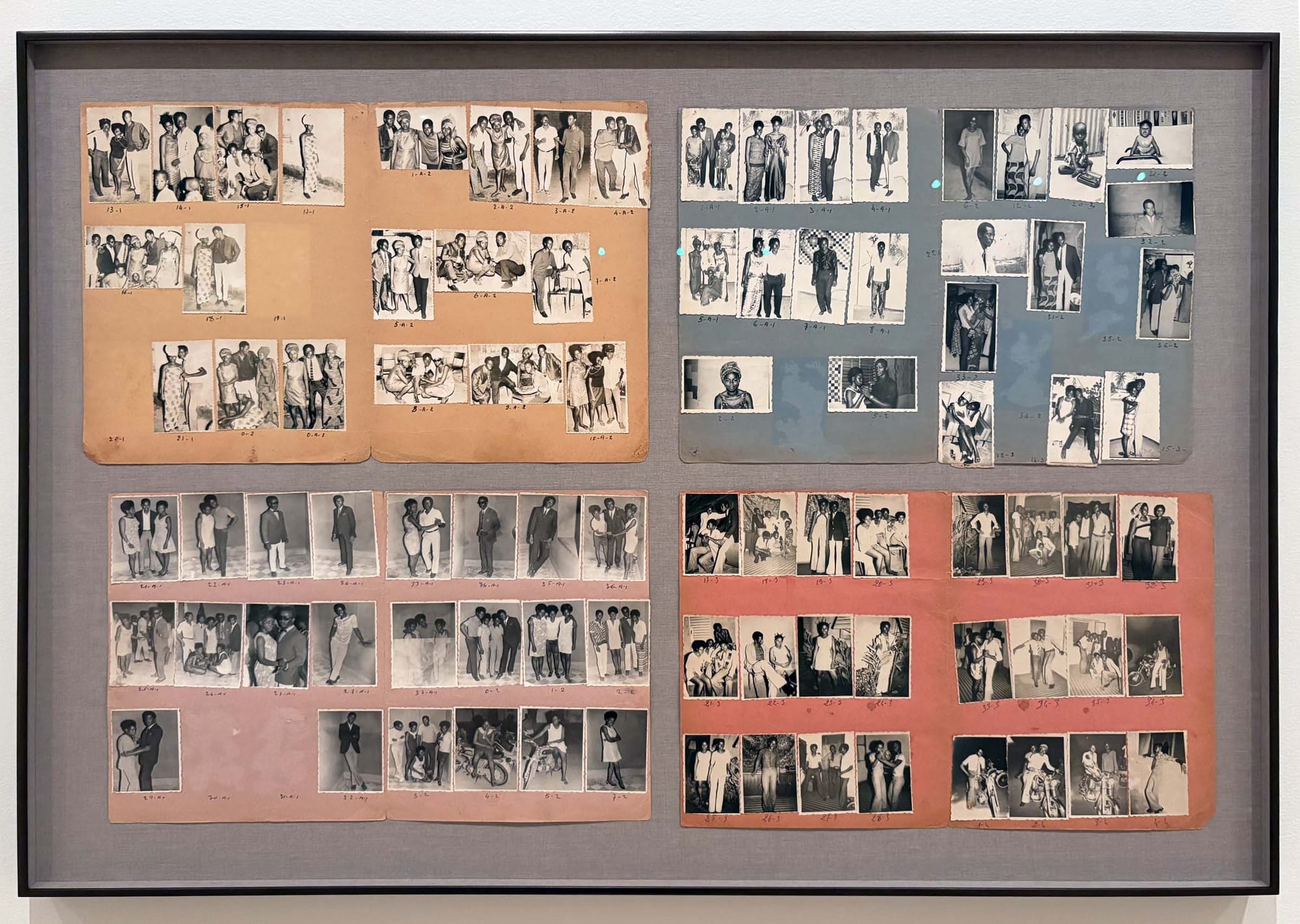

Works by Malick Sidibé and Sanlé Sory, meanwhile, offer a mix of large and small-sized studio portraits or candid photographs of home life and private gatherings. The contrast between the sizes calls attention to the employment of these portraits as shared objects for one’s intimate circle, or insiders documenting their community.

Large portraits from Samuel Fosso’s African Spirits (2008) series anchor the exhibition and are a looming presence in the gallery space. In the series, Fosso produces self-portraits of himself based on well-known images of figures across the African diaspora, including Malcolm X, Haile Selassie, Angela Davis, and Kwame Nkrumah. Fosso — a bridge between the older photographers such as Keita and younger photographers such as Rosi — perfectly encapsulates how portraits in a diaspora seamlessly circulate and influence aesthetic ideas over time, language, and geography.

Onabanjo’s vivid and thoughtful curatorial decisions squarely set “ideas” of Africa in real space, where visitors are forced to question accepted modes and structures, such as sorting artists by nationality. It presents an opportunity to examine what happens when the African diaspora defines itself and prioritizes its cultural habitus as a way of existing in the world. Portraiture is political in the African diaspora, this exhibition shows us, because it provides a springboard and testimony for the ways the diaspora can reimagine, physically activate, and address their audience as a way of being.

Ideas of Africa: Portraiture and Political Imagination continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through July 25. The exhibition was curated by Oluremi C. Onabanjo with Chiara M. Mannarino.