The Importance of Making “Degenerate” Art

Here, the term is reclaimed not as an insult but as an ethical position: art that refuses neutrality, civility, or institutional comfort.

TORRANCE, Calif. — Art can amaze, soothe, offer escape, expand the imagination, grant access to someone else’s interior life, trouble deeply held beliefs, critique entrenched social norms. At FOG Design+Art a few weeks ago, for instance, I was surrounded by inspired, challenging, strange work that was, in large part, affirmative — a testament to human ingenuity and the capacity to create beauty. That Saturday afternoon, a man was shot and killed by two border patrol agents while trying to help a woman who’d been pushed to the ground. Not only was it difficult to focus on anything else after that, but it felt irresponsible to do so. It was in this state of mind that I visited DEFENDING ETHICAL INTEGRITY (D.E.I.): The New Degenerate Art at the Torrance Art Museum, and encountered work that invited me to stay where I was — to refuse looking away.

I entered the gallery to the sound of protesters chanting, “Say it loud, say it clear, immigrants are welcome here” and “no aceptaremos una América racista” (we will not accept a racist America), from Elana Mann’s video work “Call to Arms” (2015–25). Beside the screen stood one of her arm-shaped acoustic sculptures: a cast cupped hand with a puncture in the center of the palm that allows sound to travel through the forearm out the fluted opening. In the video, performers press the sculpted limb to their mouths, transforming the body into a conduit for amplified speech, and overcoming efforts to silence dissent.

Ceramic hands also cover the towering collaborative sculpture in the center of the gallery, “Con Nuestros Manos Construimos Deidades (With Our Hands We Build Deities)” (2023), by the group Art Made Between Opposite Sides (AMBOS). Glazed, painted, inscribed, and embellished, the open palms hang from multi-colored knotted and braided cords. Interspersed among them are hand-sewn patches embroidered with various images and messages. On one, the words “I am choosing to believe the future can be beautiful” are surrounded by brilliant cadmium blossoms and a salmon-colored monarch butterfly. On another, the words “Abolish ICE” and “Save the Children” frame a lighted candle. It was the latter that got the sculpture, along with Mann’s video installation, removed from Pepperdine’s exhibition Hold My Hand in Yours this past October, as it was deemed too "political" for campus display.

Both works might have been labeled “degenerate” and included in the Nazi Party’s 1937 Entartete Kunst (Degenerate Art) exhibition, which sought to shame modernist artists as threats to moral order. Here, the term is reclaimed not as an insult but as an ethical position: art that refuses neutrality, civility, or institutional comfort when those postures function as cover for violence and bigotry.

The entirety of the human body, not only hands and fists, appears in much of the work on view. Polly Borland’s two grotesque, lost-wax cast aluminum sculptures depict the kinds of bodies fascism once classified as “unfit”: disabled or deformed, defying standards of physical perfection. “Teeth” (2024) features a row of enormous orbs where the mouth might be; a bulbous growth emerging from the hip; amputated arms; exposed, ambiguous genitals; and lumpy, unstable legs.

Elsewhere, Patrick Martinez and Jay Lynn Gomez’s tender “Labor of Love” (2022) — a life-size cardboard cutout of a woman cleaning a facade of emerald tile and violet stucco beneath a neon OPEN sign and pair of LED ticker tapes — memorializes the invisible laborers who maintain our cities.

Hugo Crosthwaite’s stop-motion animation “A HOME FOR THE BRAVE” (2020) is the show’s most potent confrontation with state violence. The film makes visible what policy and propaganda obscure. In it, migrants, mostly women and children, are shot by uniformed men, their bodies turned into bullseye targets and skeletons. In one scene, a family appears under what seems to be the fluorescent lights of a federal building, before the image is violently torn apart; in the next frame, a woman is trapped behind a metal fence.

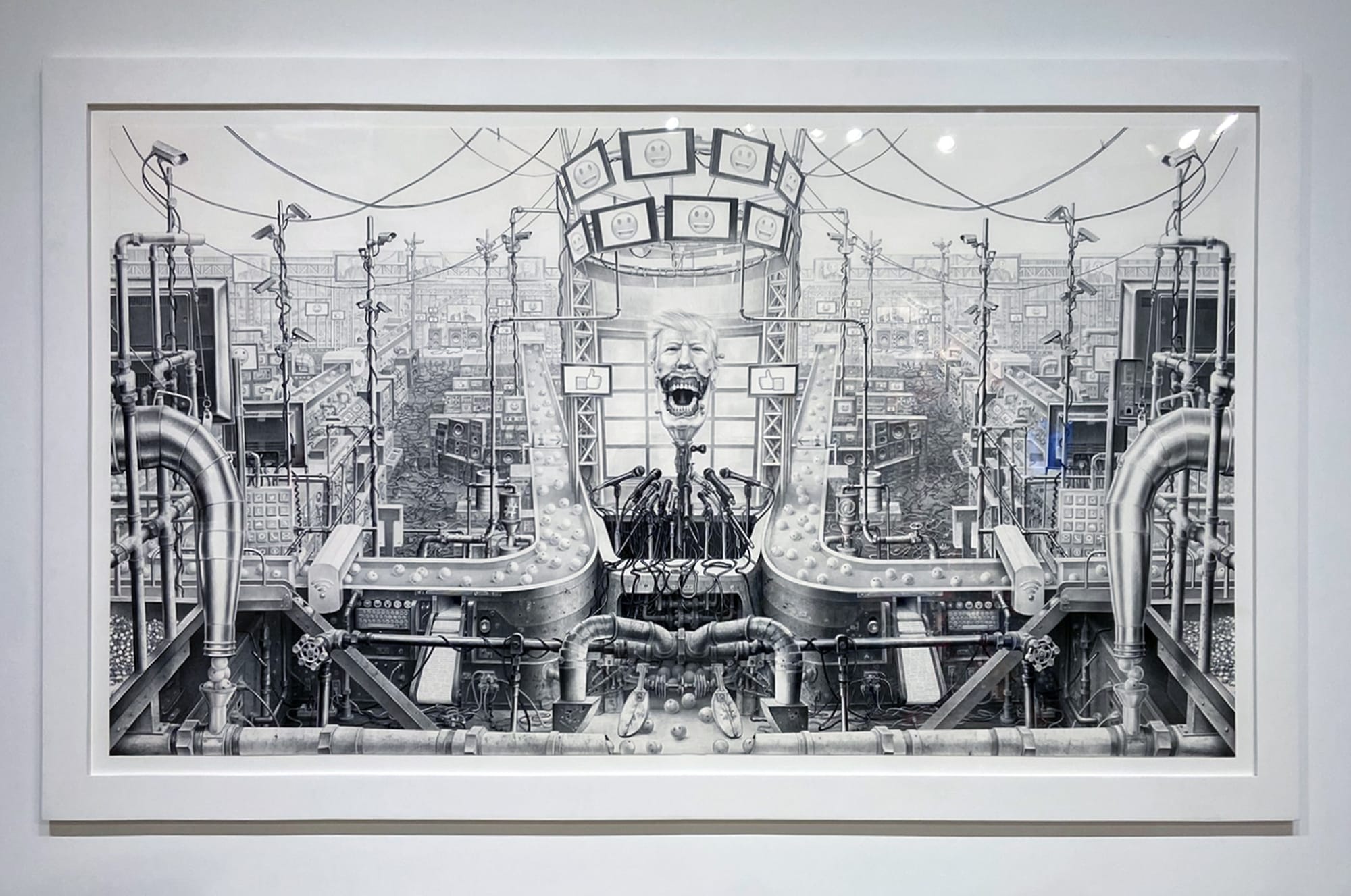

This emphasis on embodiment runs counter to Laurie Lipton’s monumental charcoal drawing “POST TRUTH” (2017), which depicts President Trump as a cyborg controlled by an industrial media system. Rendered in meticulous detail, the president’s head, hoisted on a metal stand before a dozen microphones, is surrounded by delirious, retro-futuristic machinery filled with winding wires, circuits, pipes, and gears that connect screens, speakers, and amps. Facebook “Like” icons, smiley faces, “@” signs, hashtags, and emojis seem to fuel the apocalyptic factory. Nearby, the bodies implicated but absent from the stainless steel cheese-grater slide by Nadya Tolokonnikova of Pussy Riot feel equally haunting.

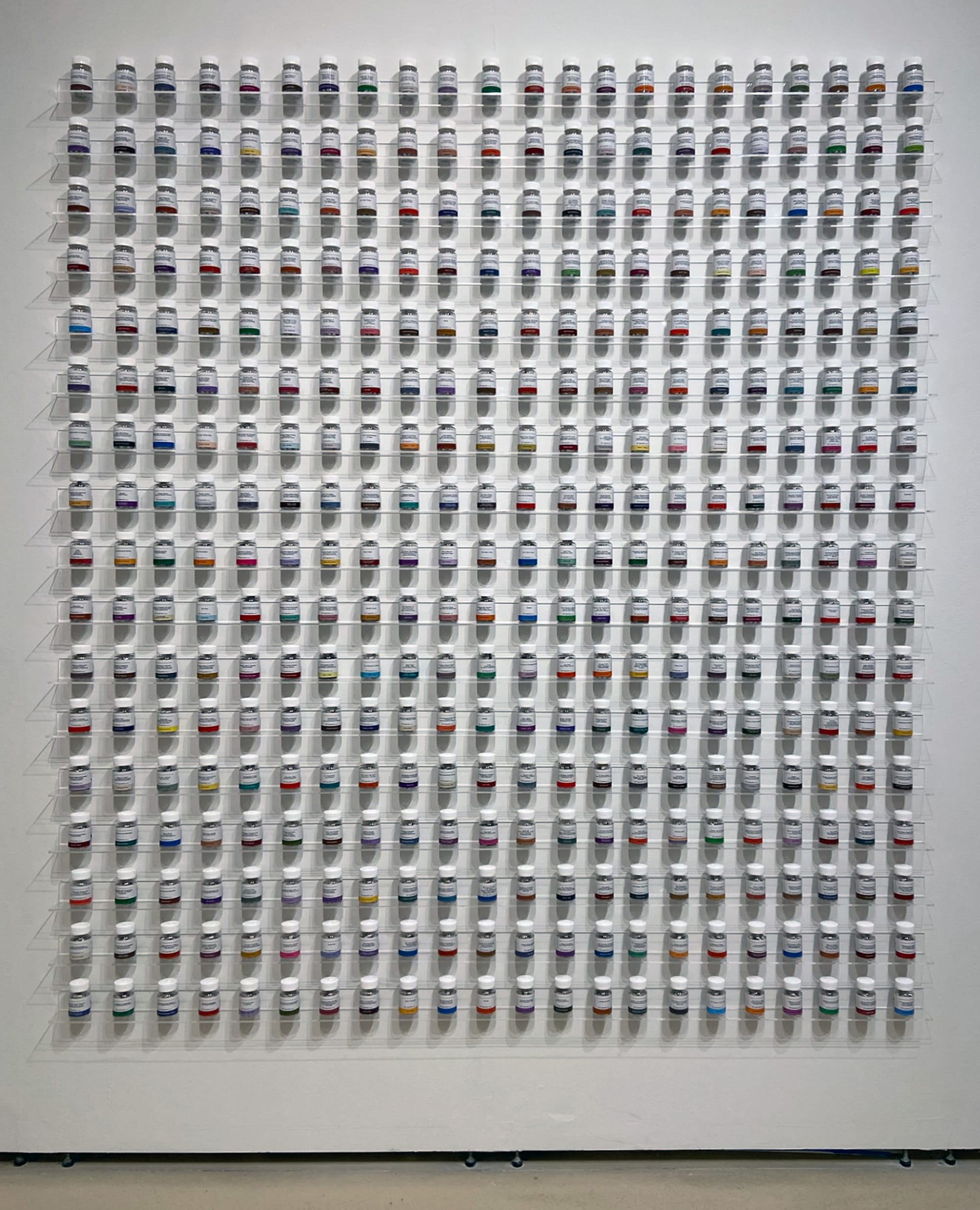

Before I leave, I stand before Steven Wolkoff’s wall of 376 medicinal vials labeled with the titles and authors of books removed by Defense Secretary Pete Hegseth from the United States Naval Academy Nimitz Library. Gender Queer (2019) by Maia Kobabe, How to Be Anti-Racist (2019) by Ibram X. Kendi, and I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings (1969) by Maya Angelou are among the banned books that Wolkoff burned — “sanitized with fire,” he calls it — and pressed into cellulose capsules. I can’t help but fantasize about what it might be like if people could swallow a pill and suddenly feel what it’s like to be someone else, someone other. It may be naive of me to still believe that would change everything. But at this point, what remains if not hope — for empathy, for understanding?

As Angelou wrote, “the quality of strength lined with tenderness is an unbeatable combination.” To take in these stories is to feel their rage and passion — emotions that render silence impossible.

DEFENDING ETHICAL INTEGRITY: the new Degenerate Art continues at the Torrance Art Museum (3320 Civic Center Drive, Torrance, California) through February 21. The exhibition was curated by Jenny Hager, Ty Pownall and Steven Wolkoff.