The Marquis de Sade of the Upper East Side

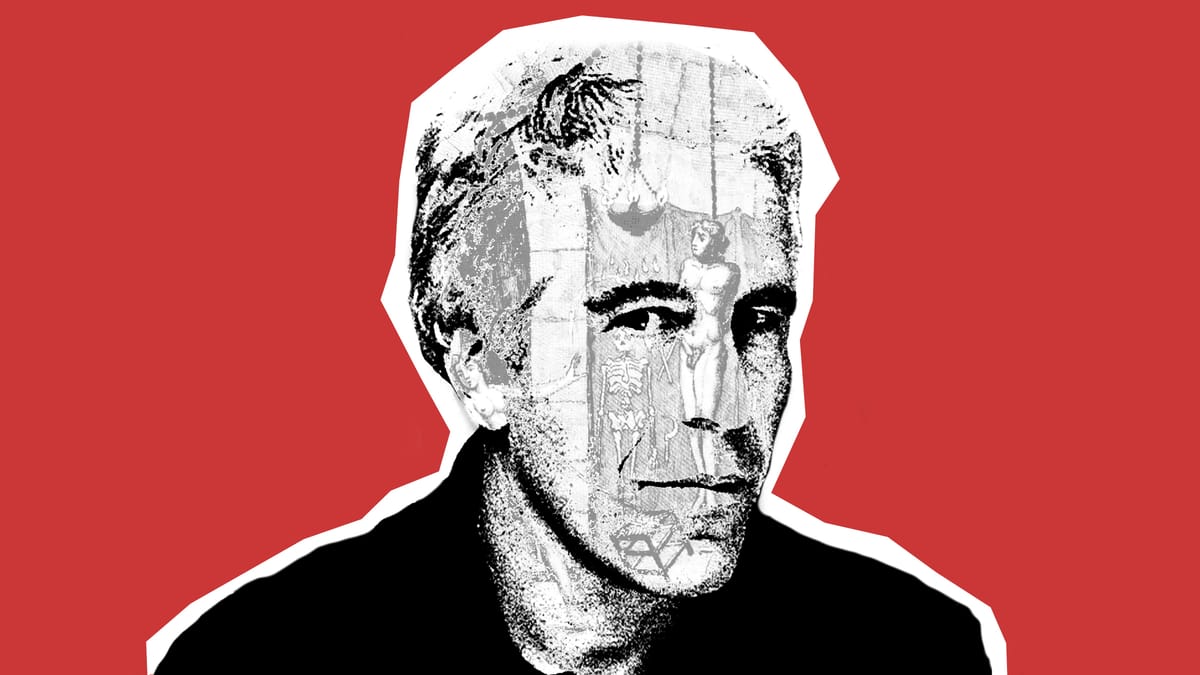

Like the infernal French nobleman, Jeffrey Epstein’s story represents cruel and oppressive politics that were seeded in aristocracy, tended in capitalism, and are now harvested in fascism.

Editor’s Note: The following story contains mentions of sexual assault. To reach the National Sexual Assault Hotline, call 1-800-656-HOPE (4673) or visit online.rainn.org.

Ten days before several hundred sans-culottes and Parisian commoners, armed with filched muskets and cobblestones, stormed the Bastille, its most notorious prisoner had already been transferred. Coincidentally, it was that transferred inmate — Donatien Alphonse François, better known as the Marquis de Sade — who represented the ancien regime at its most dissolute, decadent, and depraved.

An atheist, materialist, and hedonist, de Sade was above all an aristocrat, which is to say that his understanding was of “Wolves which batten upon lambs, lambs consumed by wolves, the strong who immolate the weak, the weak victims of the strong,” as he describes it in his 1791 novel Justine, Or, the Misfortunes of Virtue. Related to the Bourbon monarchs by blood, the infernal nobleman was a creature of his class dedicated to his own pleasure and power. Whether monarchism or republicanism, de Sade’s own politics were far simpler, for whatever served him was his ideology. Were de Sade alive today, it could be imagined that he’d charm and ingratiate himself among representatives of divergent factions, perhaps equally at home with a fascist like Stephen Bannon and an anarchist such as Noam Chomsky — identically to his modern acolyte, the millionaire rapist Jeffrey Epstein.

Despite the ironically named Department of Justice’s slow, glitchy, and intentionally obfuscating legally mandated rollout of 3.5 million files related to the Epstein case, which has implicated elites including tech billionaires Elon Musk and Bill Gates, former treasury secretary Larry Summers, attorney Allen Dershowitz, Secretary of Commerce Howard Lutnick, the former Prince Andrew, and of course Donald Trump (allegedly mentioned more than a million times), a portrait of the shadowy financier’s intellectual self-regard has emerged. With his orthography and punctuation as antinomian as his morality and regardless of the unctuous superlatives directed at him by everyone from Ivy League professors to captains of industry, Epstein is a man whose ego is in inverse proportion to his actual intellectual abilities, a crank who intoned on eugenics and cryonics. Regardless, Epstein consciously fashioned himself after Enlightenment libertine forerunners, a philanthropic patron of the sciences and arts who maintained that his barely private licentiousness was warranted by his own perceived superiority.

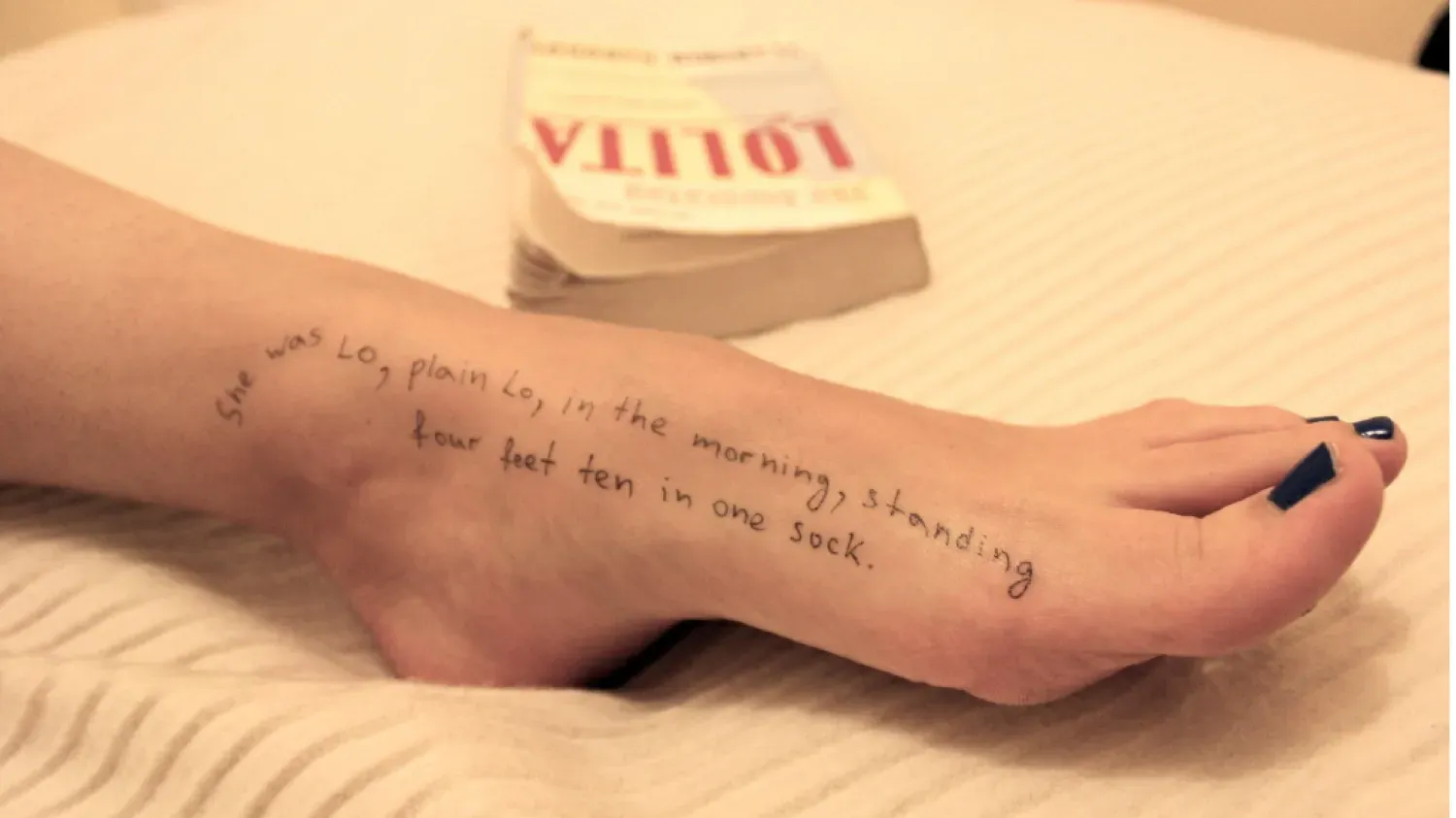

Prone to a variety of misreading common among the powerful and mediocre, Epstein apparently thought of himself as not unlike Humbert Humbert, the villain in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, apparently having kept a first edition of the novel in his Upper East Side townhouse, while his private jet shared a nickname with the protagonist, a pubescent girl groomed and raped by a pedophile. Elisa New, emeritus professor of English at Harvard who’s married to Summers, glowingly described Lolita in a 2018 letter to Epstein (a decade after he had been convicted in a Florida court for sex trafficking of a minor) as being “about a man whose whole life is forever stamped by his impression of a young girl” (spoiler, that’s not what the book is about). Whatever Epstein’s own pretensions regarding Lolita, any interpretation of Nabokov whereby Humbert is rendered a hero demonstrates the intellectual shallowness of the person performing said interpretation. Far more accurate would be to see in Epstein the dark shadow of de Sade. In the originator of Sadism, we encounter an infernal figure who, beyond even the facts of his own perversion and criminality, intimated a cruel and oppressive politics that were seeded in aristocracy, tended in capitalism, and are now harvested in fascism.

The 20th century was disturbingly kind to de Sade, valorized by intellectuals like Georges Battaile, Michel Foucault, and Simone de Beauvoir as a supposedly keen interpreter of humanity and an advocate for liberty, the philosophical pornographer whose The 120 Days of Sodom (1785), Justine (1791), and Philosophy in the Bedroom (1795) expanded the bounds of desire. Foucault waxes in The History of Sexuality (1976) how “Sade is the one who actually liberated desire from subordination to the truth.” This is a de Sade exalted into a symbol of freedom, though his was a very particular variety of “freedom.” Its victims include Jeanne Testard, a prostitute hired by de Sade in 1763, who was imprisoned, tortured, and raped by the aristocrat. Five years later, a working-class widower named Rose Keller was hired by de Sade as a housekeeper. He imprisoned her, mutilated her with a knife, and poured hot wax into her open wounds, before she was able to escape. In 1774, with shades of Epstein and Ghislaine Maxwell, de Sade and his wife hired six 15-year-old children (five girls and a boy) who were repeatedly raped and tortured by the marquis. Shockingly, for the standards of the 18th century, de Sade was imprisoned for several of these crimes, though more often than not he was able to endure despite the opprobrium of authorities, whether Bourbons or Jacobins. A recounting of de Sade’s crimes is important because it emphasizes how his transgressions were never only in the imagination. Furthermore, as the too-often dismissed feminist critic Andrea Dworkin astutely observed in Pornography: Men Possessing Women (1981), those “leftists who champion Sade might do well to remember that prerevolutionary France was filled with starving people,” so that the libertine “learned and upheld the ethic of his class.”

Decadence among French aristocrats on the eve of the revolution was a historical reality. “French nobleman of this type were not merely licentious,” writes Chad Denton in Decadence, Radicalism, and the Early Modern French Nobility: The Enlightened and the Depraved (2016), “but had legitimized their lifestyles … normalizing modes of behavior alternative to traditional moral prescriptions.” A tragedy of etymology is that Sade’s name has been turned into an adjective that’s applied to even ethical paraphiliacs (consensual kinks such as S&M), but the writer’s sexual amorality had nothing to do with consent. Indeed, consent was precisely the target of de Sade’s thinking, for any attribution of agency, independence, or self-possession among those whom he viewed as weaker than himself was the primary ethic he inveighed against. A pleasure in the denial of others’ humanity; a philosophy that doesn’t just resent individual consent, but even its possibility. Rape as a metaphysic. That this is the ethic of his class, albeit pushed to its logical conclusion, goes without saying; even more so, that it’s the motivating belief of the ultra-rich capitalist class in our current moment. Placing pleasure at the apex of worthiness is one thing, but de Sade was not merely some Epicurean, for it must be emphasized that his definitions of pleasure were specifically aberrant. Not because they were abnormal (though they were), but because his definition of pleasure was explicitly in the denial of others’ rights, the treatment of them as mere things, and especially the violation of innocence.

While imprisoned at the Bastille, de Sade penned his most scurrilous work, The 120 Days of Sodom, which depicts rape, incest, torture, pedophilia, mutilation, infanticide, coprophagia, murder, and necrophilia, where the operative thinking was that “Nothing quite encourages as does one’s first unpunished crime.” This sentiment was, for both de Sade and Epstein, their operative ideology. It’s the cultural logic of both aristocracy and of unfettered capitalism, though now we’ve simply traded Versailles for Davos. Over 100 anonymous copperplate engravings from de Sade’s 1797 The New Justine demonstrate the graphic themes of violation to a disturbing degree of technical proficiency. An opus that literary critic Roger Shattuck in Forbidden Knowledge: From Prometheus to Pornography (1997) described as the "literary equivalent of toxic waste,” evidenced well by its illustrations. In one, an orgiastic assemblage pleasures themselves as a constrained woman’s back is broken upon a wooden wheel; in another, a nude and erect man is executed by a naked woman who kicks over the chair that he stands on so that he is hung; in another, a group of gleeful aristocrats defenestrate a naked woman into a courtyard where she falls to her death, joining another woman’s corpse that is in the midst of being ripped apart by enraged dogs. There is, as a matter of course, nothing of empathy or humanity in any of these depictions, nor does the sometimes-defense of de Sade as a “satirist” square with his own monstrous behavior. “Our acts of destruction give … new vigor and … energy,” wrote de Sade in Justine. Not just the attitude of a criminal, but a self-satisfied one. The same casual language of Epstein emailing Emirati Sultan Ahmed bin Sulayem, “I loved the torture video,” or Barclay’s CEO Jes Staley writing, “Say hi to Snow White,” possibly in reference to a young girl dressed as the character, of the email sent by somebody whose name was redacted reading “Your littlest girl was naughty,” and another email which simply read “Age 10.”

Predictably, the released files are replete with connections to wealthy tastemakers in the art world. Collectors such as Stephen Tisch, Jean Pigozzi, and Leslie Wexner were friends, colleagues, associates, and visitors. Leon Black, a board member at MoMA, paid Epstein $158 million for tax and estate planning services, while Thomas Pritzker, former president of the board of the Art Institute of Chicago, was a correspondent. Jeff Koons was a Manhattan dinner guest and former Whitney Museum director David A. Ross discussed an imagined exhibition that was to be entitled Statutory, featuring pornographic photographs of underage children, with the curator calling the idea “incredible.” A prodigious art collector himself, though with distinctly abject sensibilities, his holdings included a bronze statue of a nude woman by sculptor Arnaud Kasper which Epstein outfitted in a wedding dress and hung by a noose from a chandelier as if an engraving from Justine, a hallway lined with prosthetic glass eyeballs, and a mural in his townhouse of the financier in a prison yard (apparently he was not without some self-awareness). Most disturbingly, there was the recently revealed “mask room” at his Little Saint James compound. In a yellow room, a dental chair is surrounded by a dozen doll-like masks whose identities range from Charles de Gaulle to a red-nosed clown. Examining disconcerting images such as the photographs of the mask room, it’s hard not to fear that this was art intended not to be looked at by a viewer, but rather to gaze back at Epstein’s victims.

A political chameleon, de Sade was at least consistent in his own sociopathic narcissism and cruelty. Chief among his talents—for writing wasn’t one of them—was that of being a survivor, and after the Jacobin ascension the marquis suddenly became "Citizen Sade," though as the revolution consumed itself, he too was marked for execution, saved only by Robespierre’s fall. “The mechanism that directs governments cannot be virtuous,” wrote de Sade in Juliette, and he was certainly not that. Nor, apparently, does that describe our necrotic leaders across government and industry, academia and the media, and often across partisan and ideological lines as well. Much of the collective societal trauma so many are experiencing is because it feels as if a veil has been lifted after the confirmation of how so many of the elites talk about those of us that they consider lower than themselves, the way in which suddenly the most fevered and lurid conspiratorialism appears possible. That this new awareness, alongside what is arguably the most scandalous attempted government cover-up in US history, should accompany the metastasizing of a totalitarian state isn’t incidental. Analyzing de Sade, critical theorists Theodor Adorno and Max Horkheimer concluded in their 1947 Dialectic of Enlightenment that the sadist’s corpus evidenced how “private vice constitutes a predictive chronicle of the public virtues of the totalitarian era,” while in 1945 the French writer Raymond Queneau remarked how the author of The 120 Days of Sodom acted as a “hallucinatory precursor of the world ruled by the Gestapo, its tortures, its camps.”

As the federal government consolidates a growing constellation of nearly 200 concentration camps, kidnapping and human trafficking thousands (nearly 400 of them children), that such policies are authored by Epstein associates like Pam Bondi, John Phelan, Robert F. Kennedy Jr., Bannon, and of course Trump, is shocking but not surprising. Nor is Epstein’s relationship with 4chan founder Christopher Poole, whose “/pol/” message board ironically did so much to spread PizzaGate conspiracies that appear unnervingly to have echoed the horrors of Little Saint James. When “incel activist” and avowed fascist Nick Fuentes, increasingly a mainstream figure in today’s GOP who has openly expressed admiration for Epstein, advocates for the detention of all women into gulags, there are shades of de Sade’s political prescription for involuntary brothels. Increasingly, ours feels as if it’s de Sade’s world.

What all of the conspiratorialism obscures, however, is just how depressingly prosaic and mundane Epstein’s coterie was, for finally, the most disturbing facet is that what differentiates him and his circle from the widespread preponderance of other child molesters is simply that the guests on the “Lolita Express” were rich and powerful. Even with mention of cavalier horrors interspersed, much of the behavior at Little Saint James evidences a rot very deep and wide in our culture, these grotesque individuals having corollaries among predatory priests, scout leaders, coaches, and dedicated “family men,” with the biggest difference simply what’s in their bank accounts. Society looks away at the endemic assault and abuse of overwhelmingly women and children, but that looking away is also political. Banality, if not boredom, marks de Sade’s writings as well, for his only literary talent was abject honesty. Far from being a prophet of freedom, de Sade’s work only proves that there is little transcendence in transgression and scant liberty in libertinage. His was a life committed to the principle that justice was arbitrary and de Sade’s escape from the guillotine appears as confirmation of that cynicism, though, of course, the thousands of aristocratic coconspirators who didn’t avoid the scaffold demonstrated that sometimes with righteousness the wolves can be consumed by the presumed sheep.