The Medieval Dance Between Greed and God

Medieval Money, Merchants and Morality at the Morgan Library proffers example after example of the sad fate of those who hoard money.

James Pierpont Morgan, if not rolling in his grave right now, may be shifting uncomfortably: many books from his very own collection of medieval manuscripts are on display at his very own library, each one open to a page subjecting wealth or the wealthy to the harshest of judgment. Like the medieval ethics on which it draws, the Morgan’s exhibition Medieval Money, Merchants and Morality proffers example after example of the sad fate of those who hoard money, profit excessively from transactions, and fail to give to the poor — that is, until the encroachment of the mercantile economy, when wealth became appreciably less troublesome, perhaps since it was so much easier to attain.

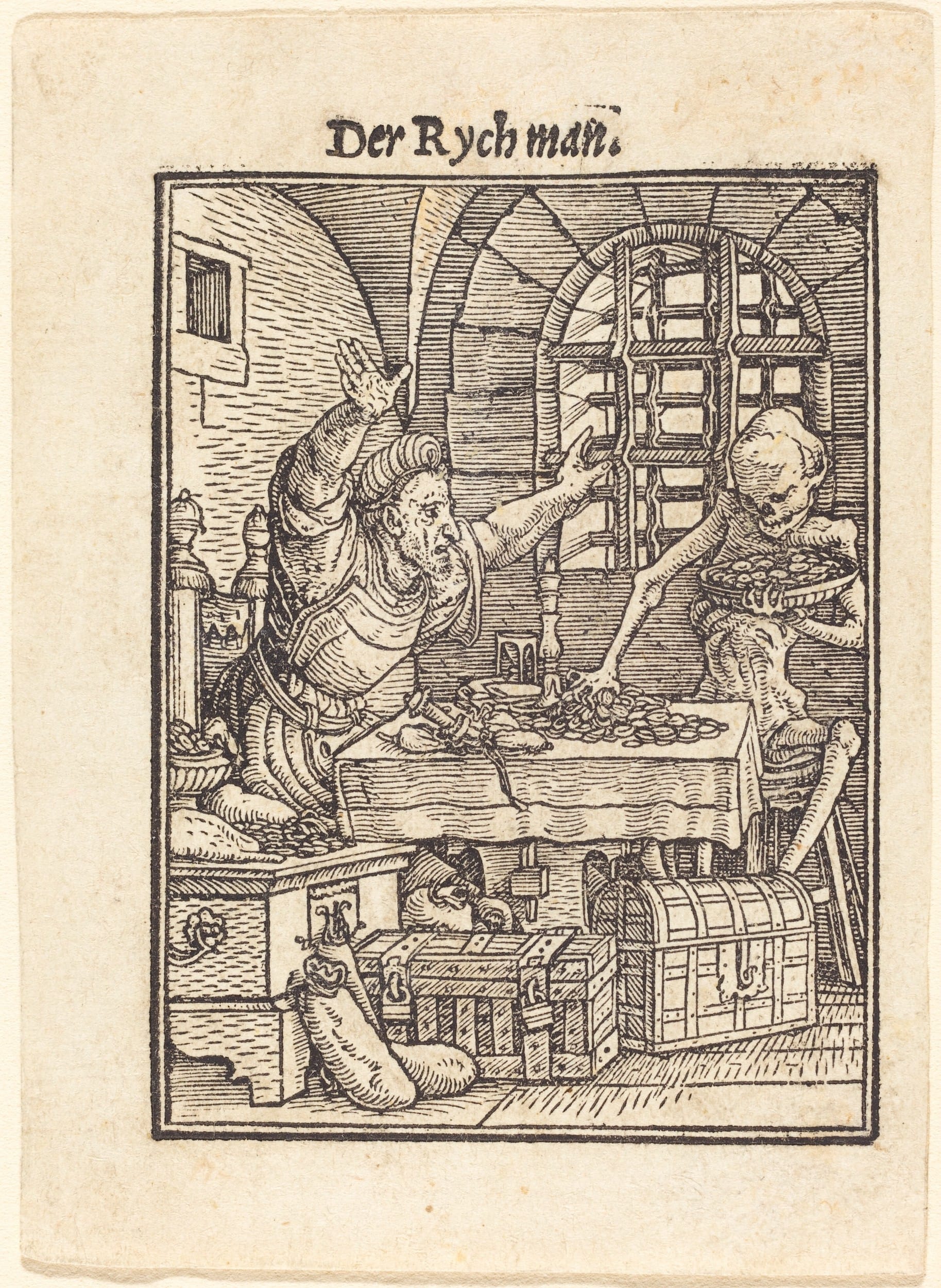

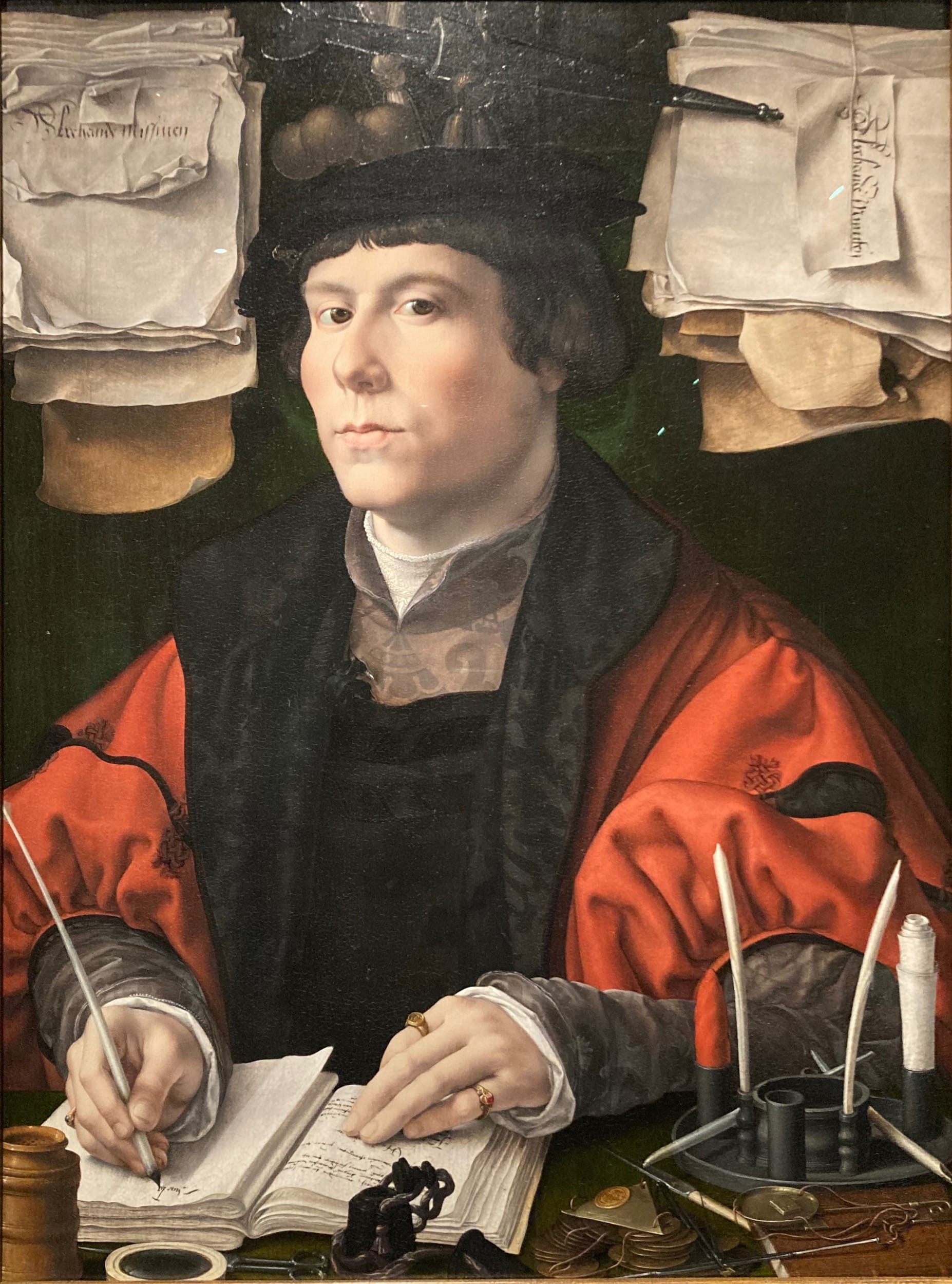

In the early 12th century, a miser is depicted in limestone, noose around his neck and gripping a bag pendulous with coins. He buckles under the weight of his money as a demon stands behind him, his hands heavy on the miser’s head and shoulder. The desire for money has him in his grip, and soon he shall hang as lifeless as his money bag. Compare this to Hieronymus Bosch’s “Death and the Miser” (1485–90), which holds out hope for the miser. Although his room is infested with demons and Death looms at the door, a kindly angel tries to direct the man’s attention to an image of the Crucifixion in the window above. This potential for redemption clears the way for works like Jan Gossaert’s portrait of a smug merchant-bro, his desk bristling with pens and strewn with coins and important-looking pieces of paper, no demons to be seen.

But between the early and later miser, there is plenty of wealth-based judgment to go around. Gambling, lending money at interest, stealing, cheating — all of these morally questionable money-making endeavors come in for punishment. More demons appear, too, many of them quite (unintentionally) endearing. In the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, for instance, souls bathe in the cleansing fires of purgatory, glimpsed through the open mouth of a cat-like creature with stoplight-yellow eyes and webbed eyelids, as a mini-demon emerges, like a bad dental problem, from between his lip and gum.

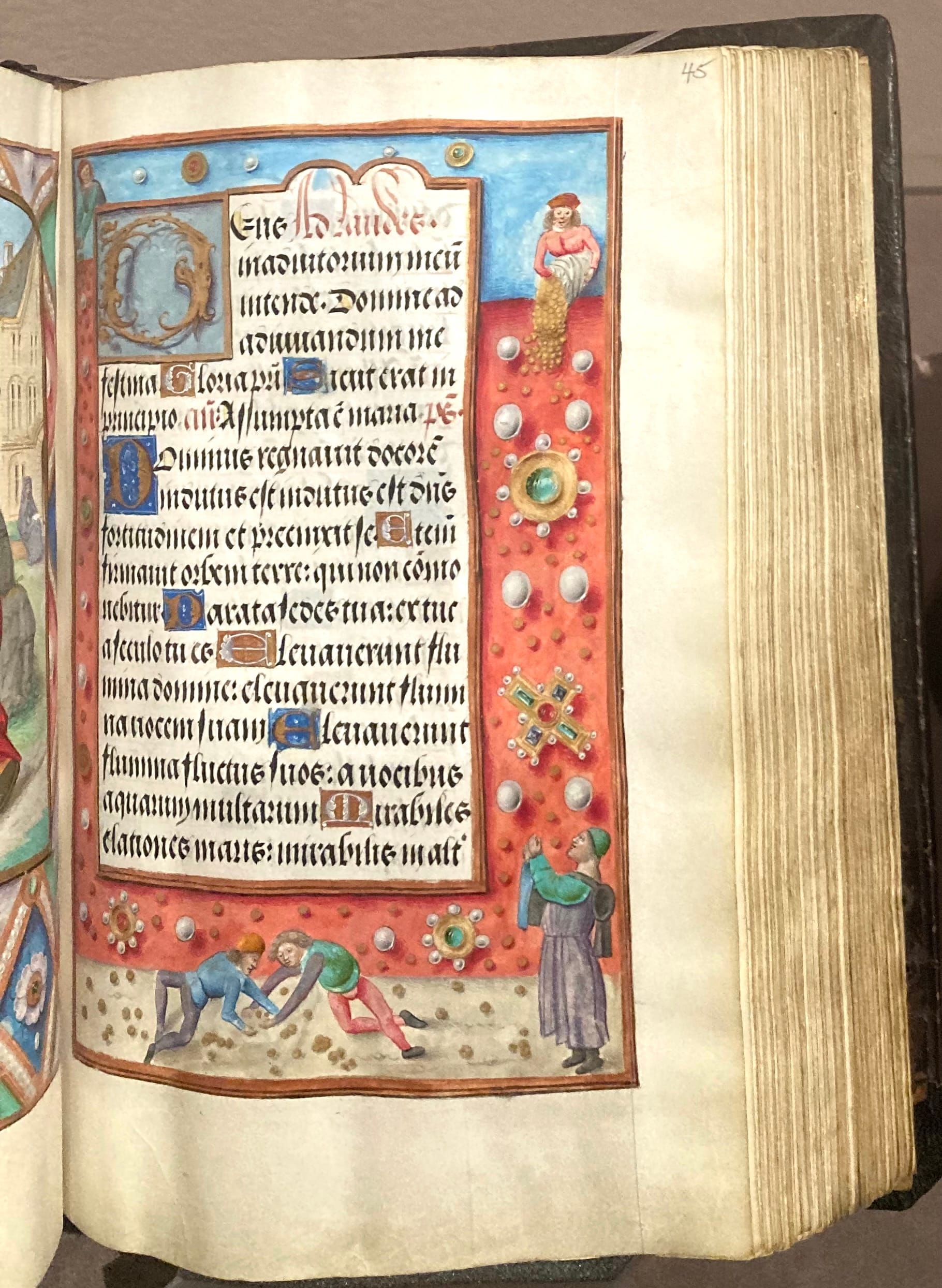

While several of the books and artworks on display make their case on less expensive paper or in multiples, the majority, ironically, are of the highest quality materials and spangled with gold leaf. In part this is due to their audience: the anti-avarice message is directed toward the rich. Yet the images do not skimp on depicting the allure of wealth. In a Belgian Book of Hours — a personal prayer book — a scene of the Visitation, when the Virgin Mary and her aunt Elizabeth are both pregnant, faces a page depicting men brawling over coins. This alludes to the blessed fertility of the biblical women in contrast with the unnatural growth of coins that results from profiteering and charging interest. The coins themselves are uninteresting brown circles, but the two pages are decorated with meticulously rendered pearls and gems that swan above the surface, making them seem like they belong more to the reader than to the book. They would be even more valuable than the coins, but as they are wealth transformed into art and accompanied by the religious figures, the viewer is free to delight in them.

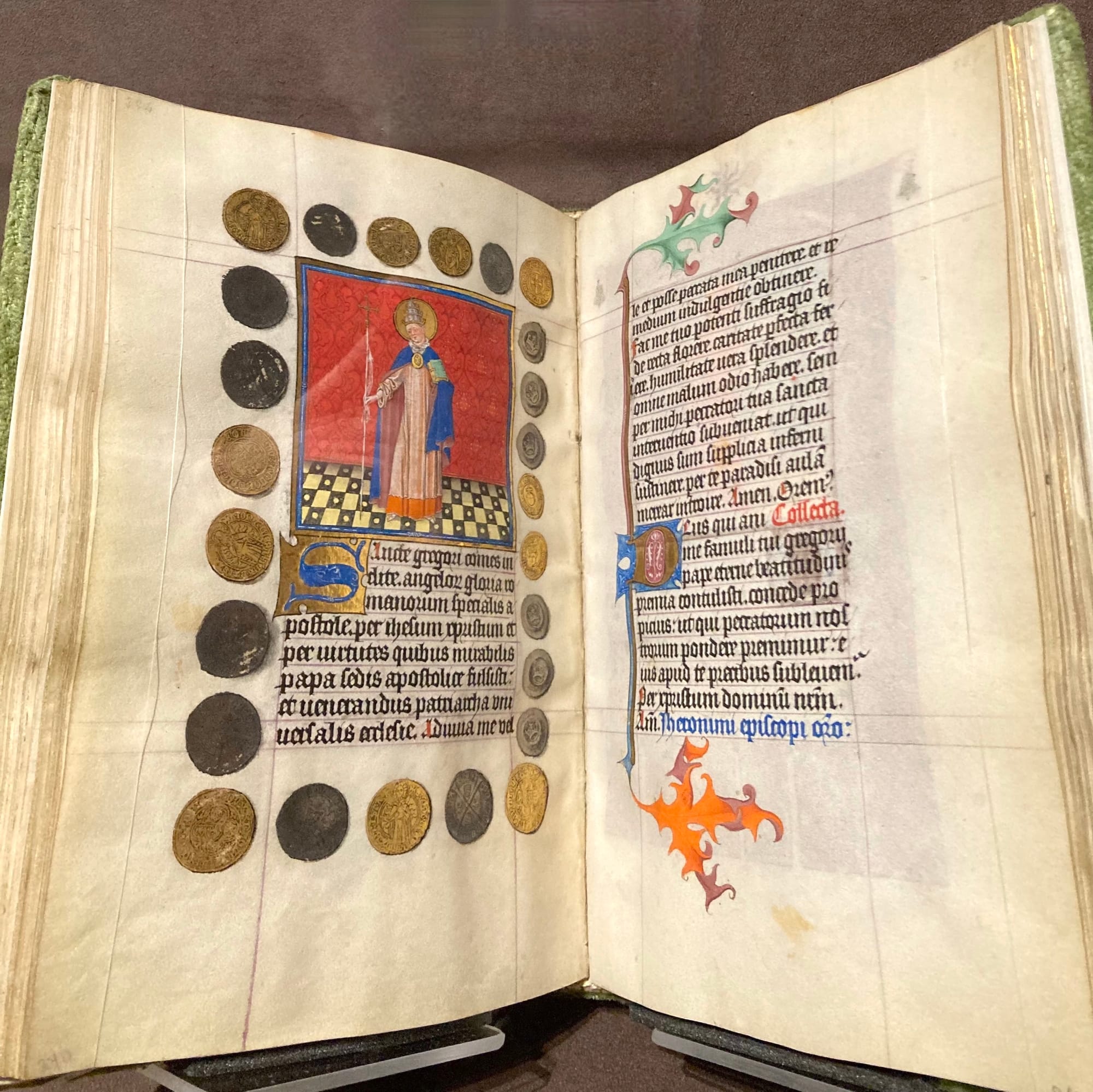

In the Hours of Catherine of Cleves, the coins take on more character. Here, the artist has rendered contemporary currencies with such (suspiciously) loving detail that most of them can be identified. They surround a portrait of St. Gregory the Great, perhaps because he was generous with his personal wealth as well as that of the church. His generosity also helps counteract the presence of the coins, or perhaps create a productive tension between appreciating his virtue and ogling the coins and trying to calculate their possible value.

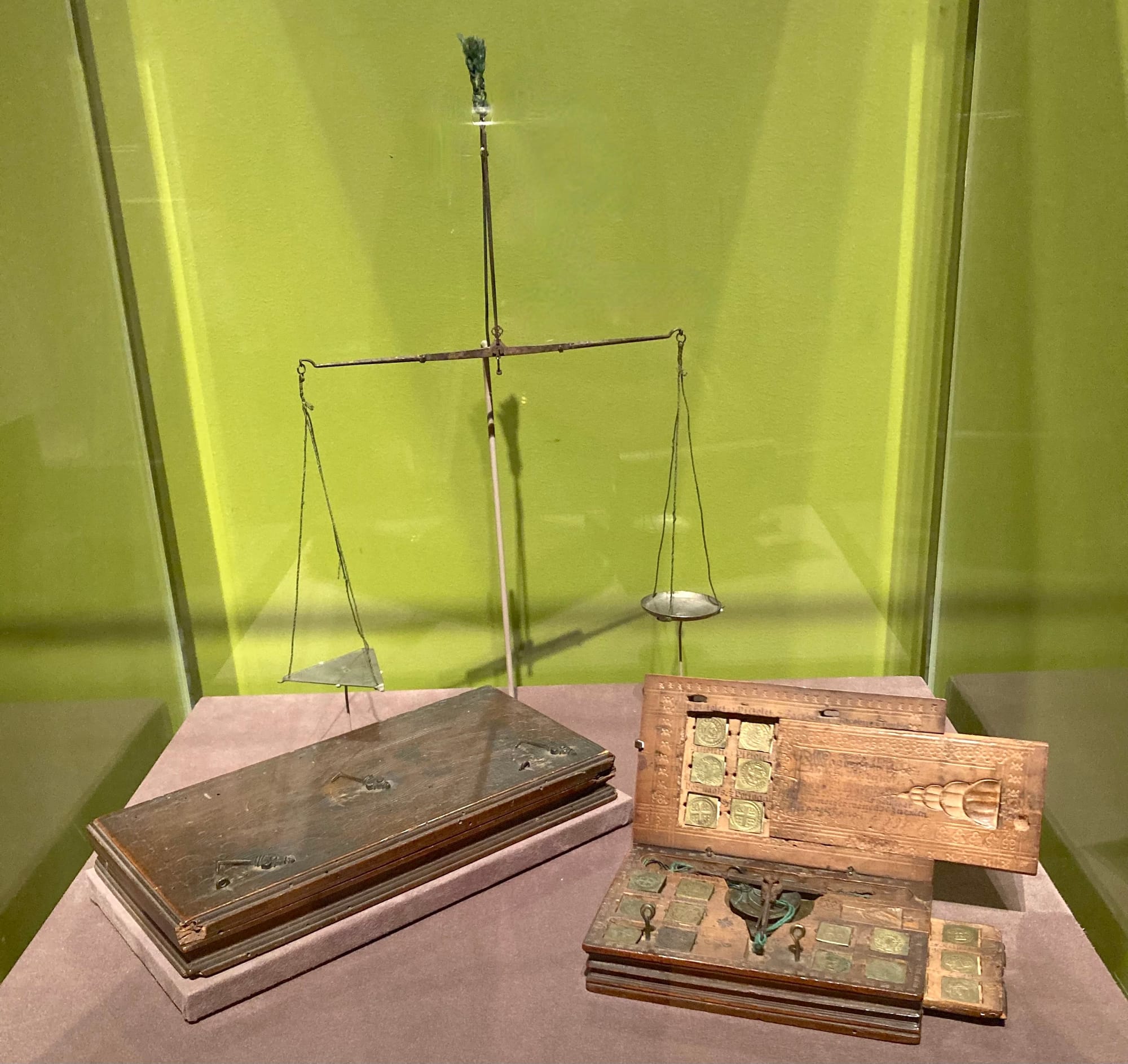

I say “possible value” because one of the distinctive aspects of coins in this period is that, unlike ours, which are marked with a value that is not intrinsic to the coin, the value was something that had to be carefully assessed by weighing, visual examination, the use of touchstones, or when real certainty was required, cupellation. Several of the exhibition’s most interesting items are those related to this lost material culture of money: a pile of coins, as thin as bran flakes; a balance and a set of weights, each neatly fitted into its own slot; and, best of all, a stupendously complicated strong box that that glowers at the entrance of the show.

These objects might have been of particular interest to J.P. Morgan, the banker’s son — more so, at least, than all the demons and doom. He may have also appreciated an illumination in the Book of the Customs of Men and the Duties of Nobles, or the Book of Chess, a treatise on an ideal society. It depicts a merchant-banker and a king regarding each other warily, the merchant from behind his balance and the king atop his throne. They need each other, yet the king, despite his power and fancy crown, needs the merchant a little more. The latter purveys liquidity, something the land-rich, cash-poor king needs. Not Mr. Morgan, however — his own complementary holdings (banking, steel, railroads) meant he benefited from both the wealth of the land and the self-generating capacity of money. This gave him more than enough buying power to enjoy the trappings of kingship — including his splendid collection. On second thought, he probably would have loved this show.

Medieval Money, Merchants, and Morality continues at the Morgan Library & Museum (225 Madison Avenue, Murray Hill, Manhattan) through March 10. The exhibition was curated by Diane Wolfthal, David and Caroline Minter Chair Emerita in the Humanities and Professor Emerita of Art History, Rice University, with Deirdre Jackson, Assistant Curator of Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts, The Morgan Library & Museum, New York.