The Mysterious Folk Art of America's Secret Societies

Almost every US town has one: that mysterious Masonic lodge with its borrowed Egyptian or Greek details, arcane symbols, and windows and doors that rarely open.

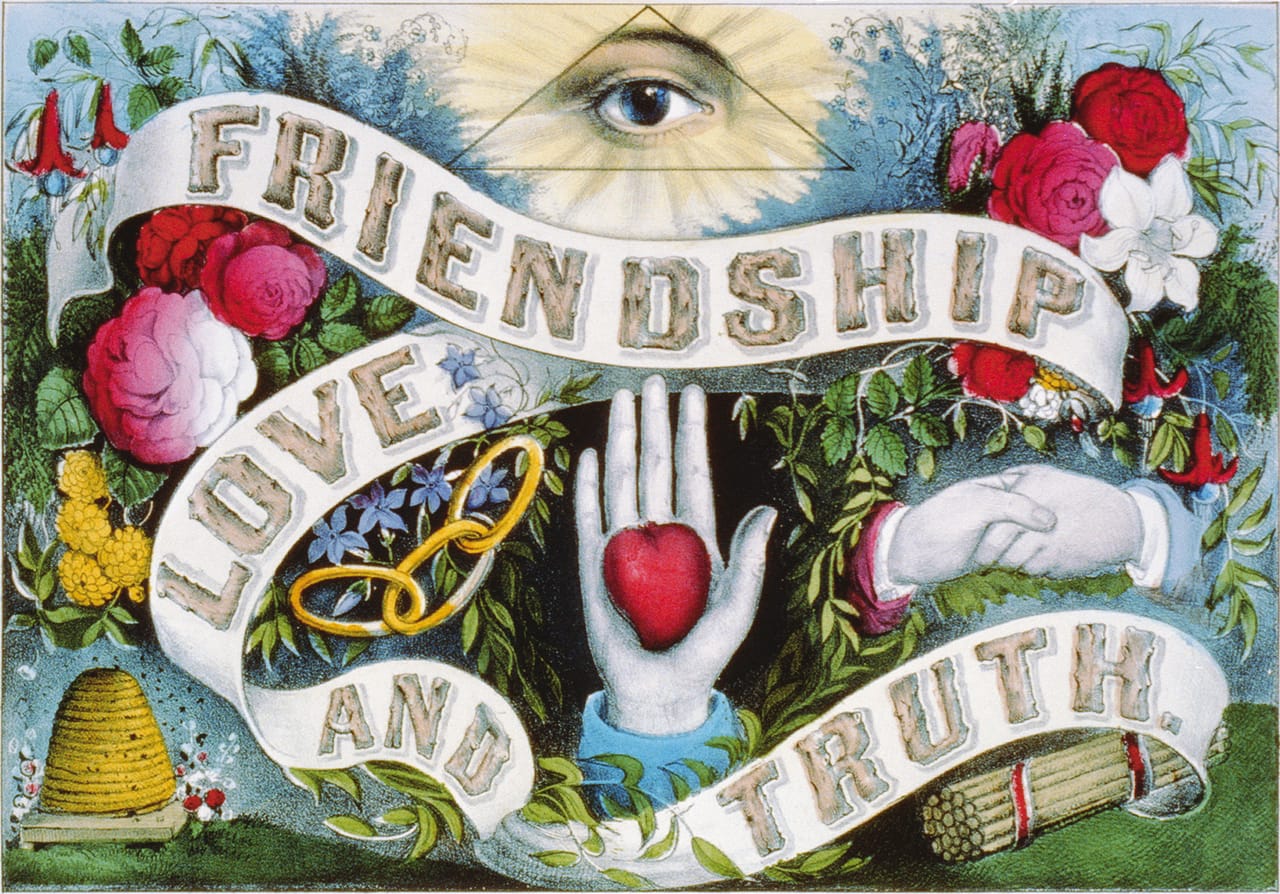

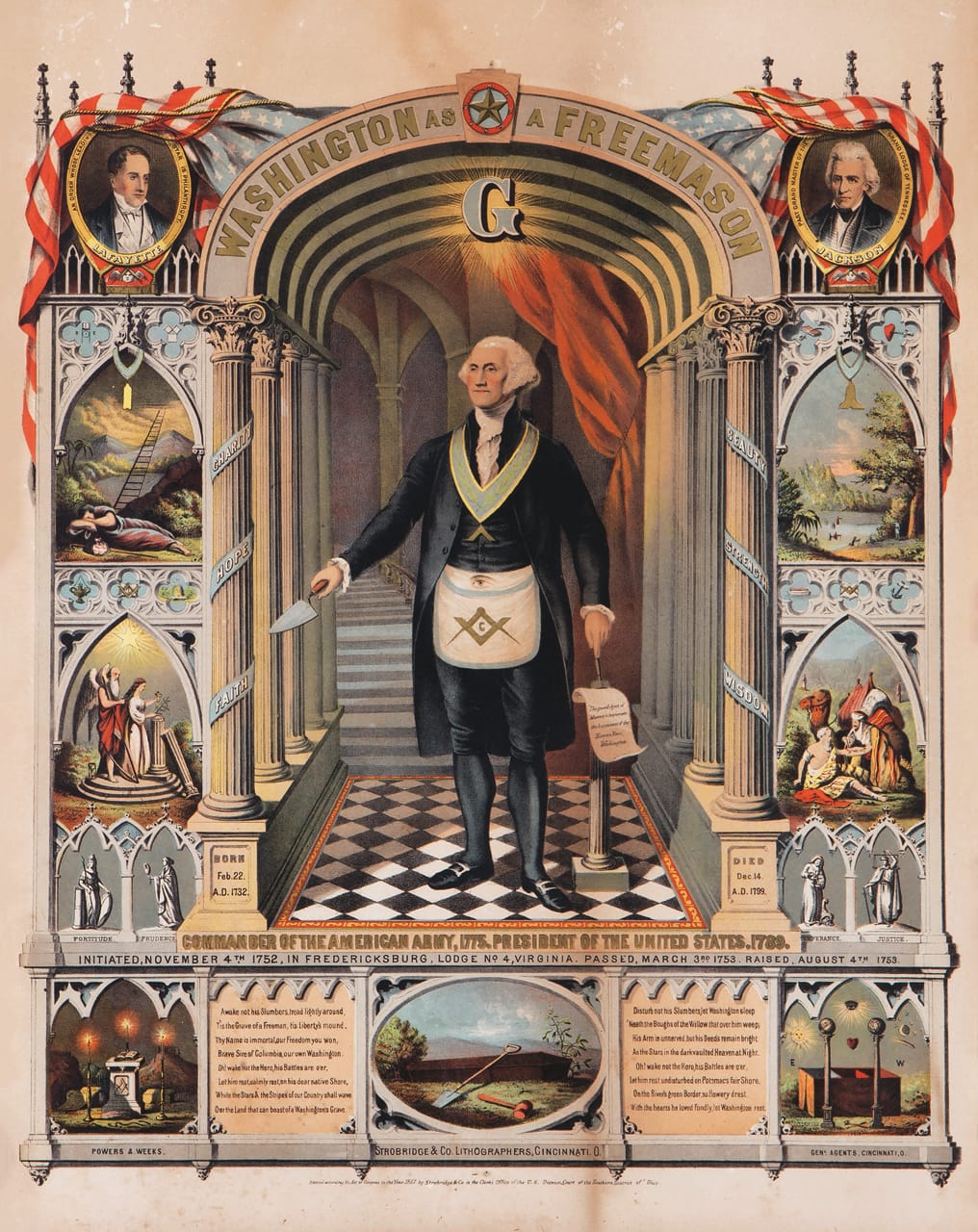

Almost every US town has one: that mysterious Masonic lodge with its borrowed Egyptian or Greek details, arcane symbols, and windows and doors that rarely open. In New York City, the huge Grand Masonic Lodge has the moon and sun painted over its entrance on West 23rd Street, while Guthrie, Oklahoma, has the even more formidable Scottish Rite Temple, with classical columns towering over the prairie lands. What are these places, why are they so pervasive, and what is that all-seeing eye watching?

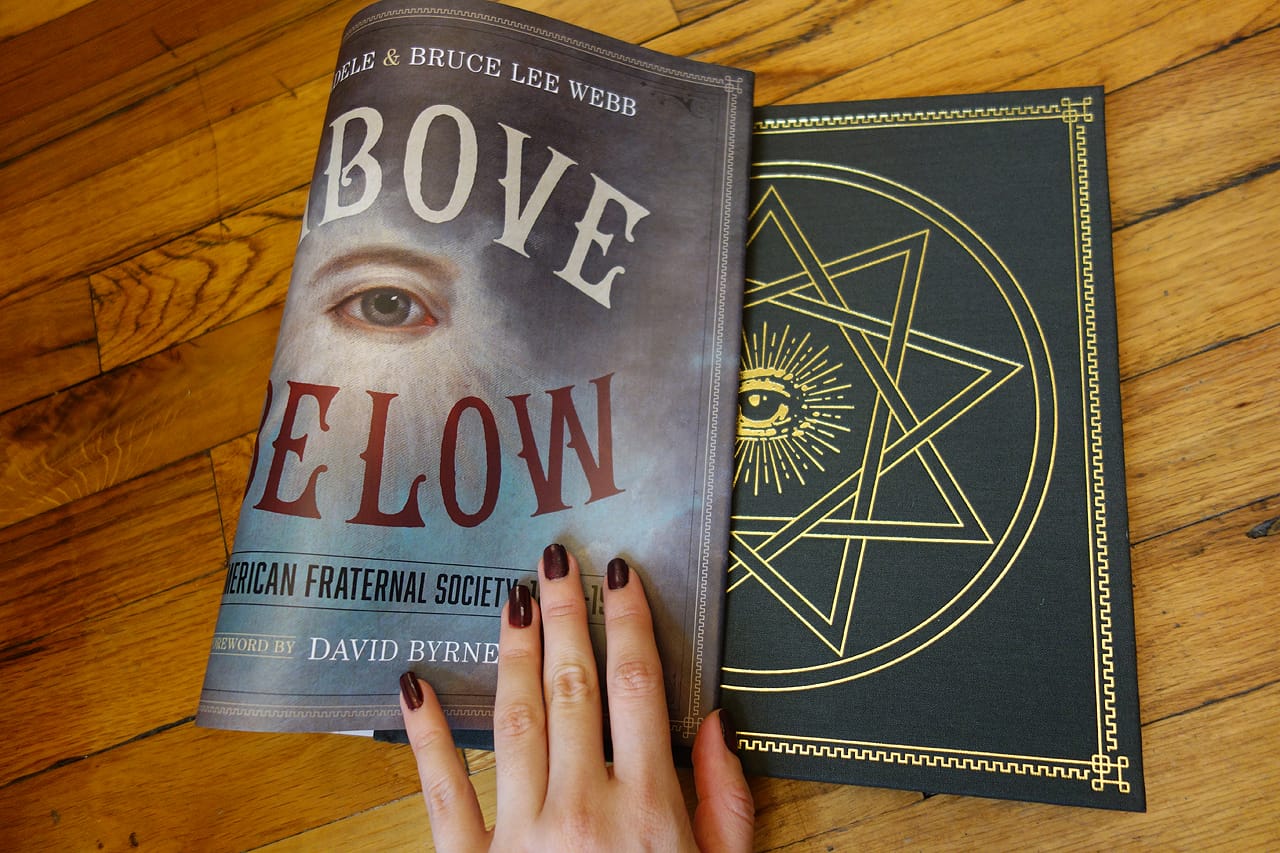

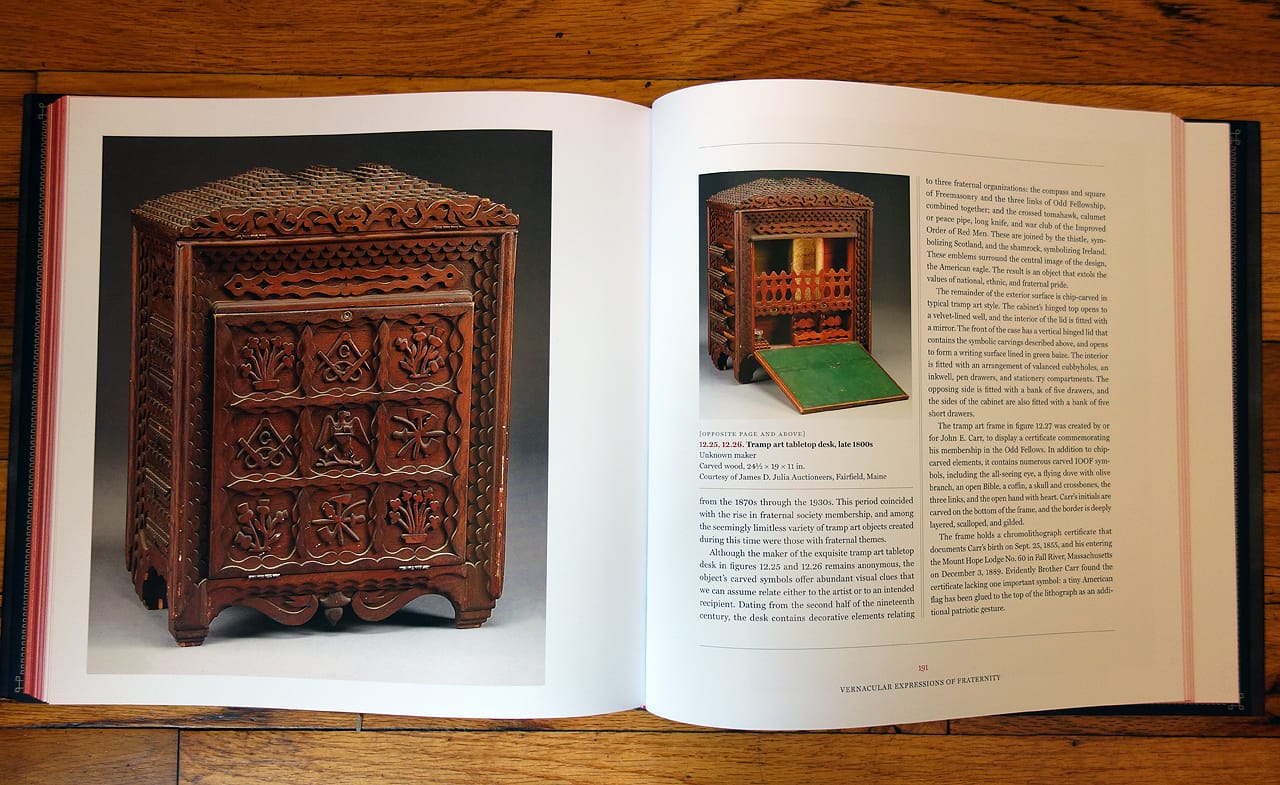

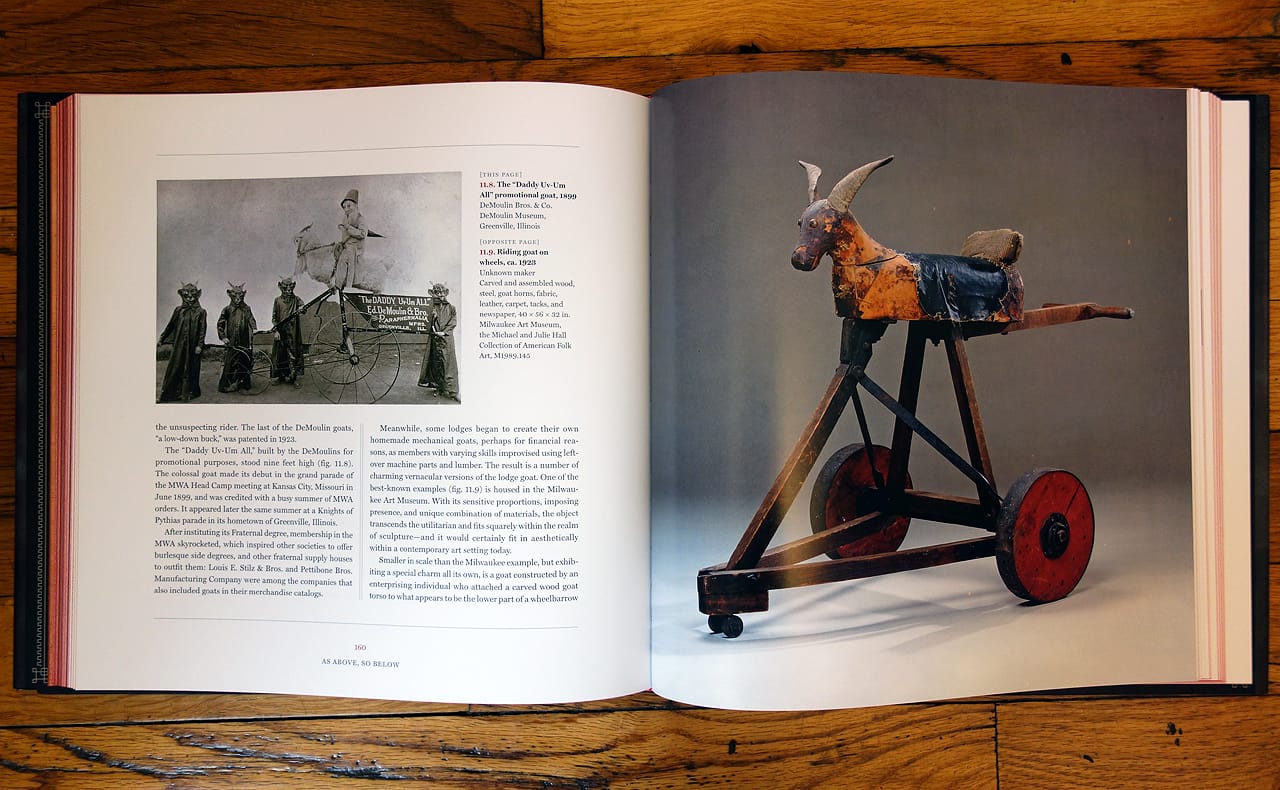

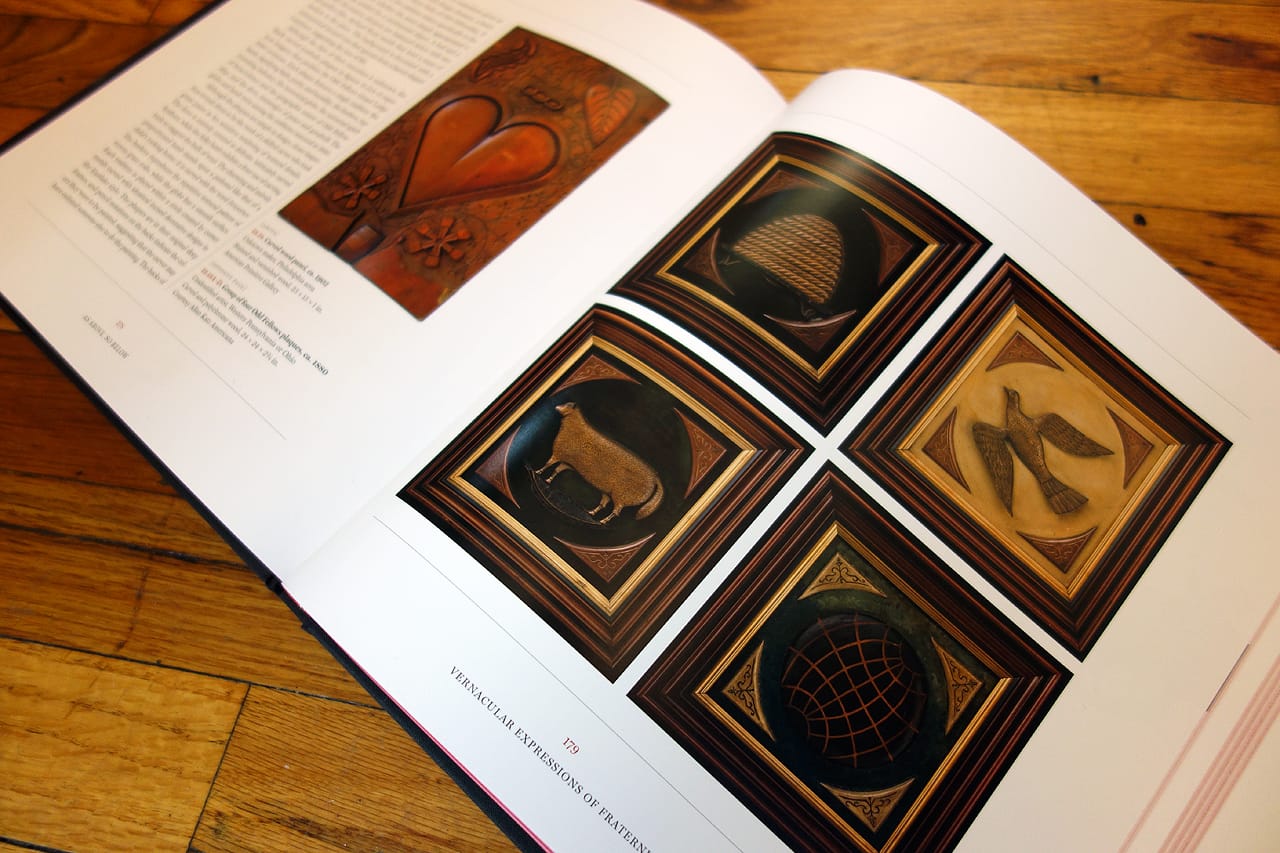

As Above, So Below: Art of the American Fraternal Society, 1850–1930 by Lynne Adele and Bruce Lee Webb, published in November by the University of Texas Press, examines the art of the “golden age” of fraternal societies. Along with groups like the International Order of Odd Fellows (IOOF), the Knights of Pythias, the Woodmen of the World, and others, the Freemasons and fellow secret societies left a profoundly strange visual legacy of papier-mâché skeletons, ostentatious costumes, ritual objects, and a few wooden goats now removed from their original contexts. Art historian Adele and fraternal art collector Webb (himself a 32nd Degree Scottish Rite Mason) unravel the history of why secret societies formed during this period in the United States and how these objects fit into the narrative.

David Byrne of the Talking Heads, who apparently also has “fraternal art collector” on his litany of hobbies, writes in the foreword that there “is an inspiring and wacky solemnity in these organizations — high values reinforced through pageantry and performance in an ecumenical social setting — which deep down must also have been a whole lot of fun.” According the book, between 1890 and 1915 it’s “estimated one in five men belonged to at least one society” in the US. That meant tens of thousands of lodges across the country, each decked out with its own regalia, some mail-ordered from companies dedicated to the demand, others very much DIY.

The members were on the whole white, protestant, and middle class, and were caught between a biblical tradition and the 19th-century frenzy for everything exotic. Memento mori skulls and sometimes real skeletons reflected a Victorian influence, while the “as above so below” idea that gives the book its title comes from occult Hermeticism.

“Although lodge membership was by nature exclusive, the lodge itself represented an egalitarian environment among members that transcended social stratification and offered leadership possibilities despite one’s social standing in the greater community; in short, it was a microcosm of middle-class upward mobility,” Adele and Webb write.

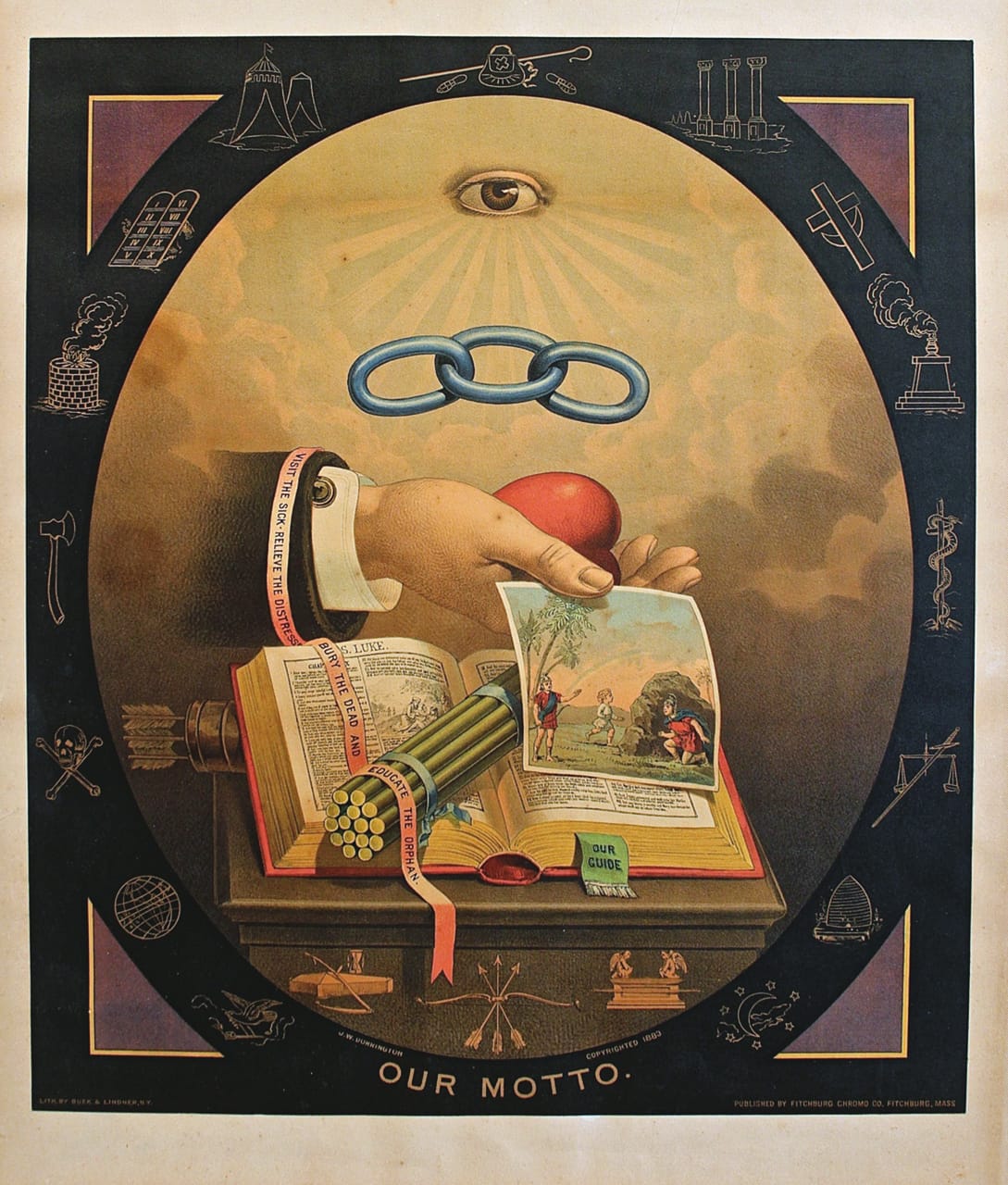

The societies were also a way to escape daily life and families, and have a bit of silly and alcohol-fueled fun. The authors describe an elaborate rite of the Woodmen of the World that’s representative of the pageantry. A blindfolded man would be burdened with objects like wooden shoes representing the “heavy loads of prejudice”; he would journey through a “forest” overseen by a masked patriarch and would have to navigate a “dangerous pathway” made by planks on rollers. Alongside the rituals were sincere philanthropic interests; the stated mission of the IOOF was to “visit the sick, relieve the distressed, bury the dead, and educate the orphan.”

The book includes over 200 objects and is a lovingly-made publication, with red-edged pages and a dust jacket that pulls back to reveal its own secret: an all-seeing eye embossed on the cloth cover. While many of the objects remain inscrutable, each represents some ritual of fraternity, where sharing a secret meant sharing a bond in a changing world.

As Above, So Below: Art of the American Fraternal Society, 1850–1930 by Lynne Adele and Bruce Lee Webb is out now from the University of Texas Press.