The Nightmares Beneath the Surface of "Dreamworld"

The traumas of war and genocide and the fascist leanings of Salvador Dalí are among the subjects that this sprawling exhibition leaves out.

Editor’s Note: The following story contains material that may be triggering to some readers.

PHILADELPHIA — When he was five years old, Salvador Dalí pushed his friend off a bridge. At 29, he “trampled” a woman after she told him he had beautiful feet. At 30, he was temporarily ousted from the Surrealist art movement because of his infatuation with Hitler. And at 35, after sending the movement’s co-founder, André Breton, letters that described “feeling real pleasure and considerable sexual excitement in reading about” the lynchings of Black Americans, his expulsion was made permanent.

Perhaps we shouldn’t expect Dreamworld, the wide-ranging commemoration of Surrealism’s 100th anniversary currently on view at the Philadelphia Art Museum, to divulge every grisly detail of Dalí’s inhumanity. But it is disappointing that it doesn’t even attempt to scratch the surface. On its face, the exhibition is impressive, offering a rare glimpse at an enormous array of Surrealist masterworks, from the legendary to the overlooked. The timing could not be better: We have much to learn in this moment from a movement that was both explicitly antifascist and radically hopeful — and from how the not-so-antifascist Dalí broke from it. But Dreamworld presents precious little of the historical and political context — for example, the birth of the movement out of the grotesque terrors of World War I — that would help viewers grasp the relevance of what’s in front of them.

Instead, it groups the art into vague categories and provides wall texts full of platitudes. Take a look at the difference between how the exhibition’s didactics describe the Surrealists’ interest in nature and that of cultural critic Naomi Klein, for instance. The wall text states: “The Surrealists believed that the rationalism associated with modern life had the pernicious effect of estranging people from themselves … Surrealist landscape painting presents natural scenery as a window into the imagination.” In contrast, Klein writes: “They attempted to merge with the natural world — anything that could provide an escape from the machinery of death that disguised itself as progress.” The result of Dreamworld's surface-level approach is perhaps the most surreal of all: a show about one of the 20th century’s most compelling art movements that is, somehow, kind of bland.

If you ignore the wall labels, a stroll through Dreamworld feels appropriately like floating across a mystical barrier into the collective unconscious. Amoeba-like blobs and severed limbs merge and collide. Umbrellas encrusted with coral descend from the heavens. Minotaurs painted by the likes of Pablo Picasso, André Masson, and Leonora Carrington roar in the distance. Monstrous chimeras and exquisite corpses foreshadow the cathartic effects of 1980s creature features. Particularly heartening is the unusually large number of works by lesser-known surrealists, including many women and artists from countries like Romania, Mexico, and Cuba, who often used the cosmological and horrifying dream space of the movement to work through horrors of war and industrialized genocide.

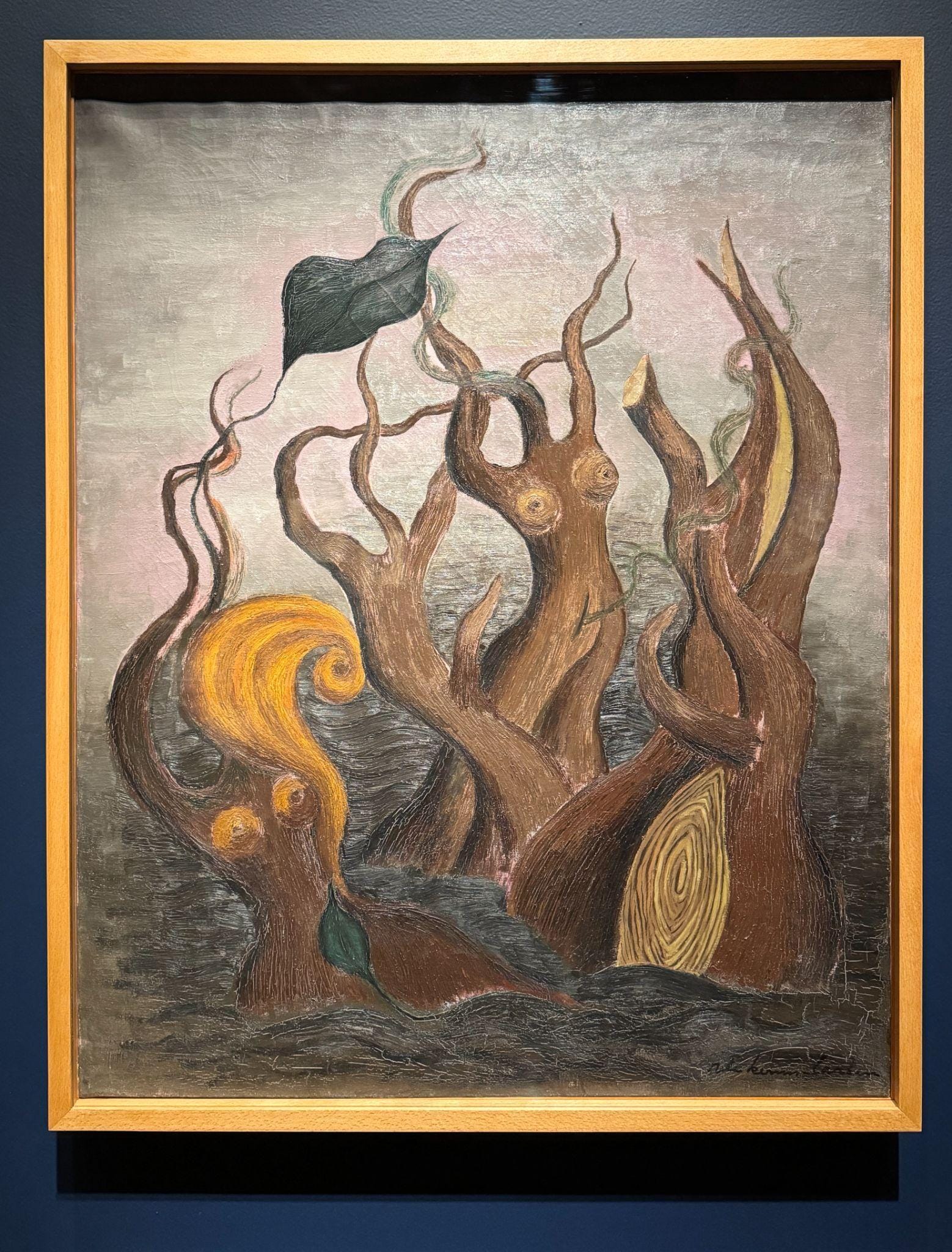

But — what is their story? Too often, the didactics contain barely any information. Who is Rita Kernn-Larsen, the rare woman in early European Surrealism, who grew up in a castle, and why did she title an unnerving 1940 painting of drowning, headless, humanoid trees grasping at the sky “The Women’s Uprising”? Why go to such lengths to include niche delights such as Suzanne Van Damme’s “Surrealist Composition” (1943–47), a floating coterie of alien creatures, if we learn nothing about who she was? How are we to thoroughly understand Surrealism’s adventures into the unconscious without learning about its origins in Breton’s work as a doctor treating traumatized World War I veterans? And how can one invoke these artists’ opposition to the specter of fascism while glossing over the very different and far more disturbing politics of Dalí, who is so prominently featured in the show?

It is unsettling to see visitors taking selfies with Dalí’s 1936 masterwork “Soft Construction with Boiled Beans (Premonition of War)” knowing that he painted it a year after he wrote to Breton praising Nazism as the pinnacle of surrealism and dreaming of the “domination or submission to slavery of all the colored races,” which “could produce immense possibilities of immediate illusions for white men.” Nowhere in the exhibition does the wall text note that Dalí was in fact rejected from the Surrealism group, let alone why. Perhaps fewer people would snap selfies next to his work, or buy the piles of Dalí merch on offer in the gift shop, if they knew that he lauded Spanish dictator Francisco Franco as “the greatest hero of Spain.”

Some have written off Dalí’s predilection for fascism due to his later claim that he only wrote about it to the Surrealist Manifesto author “precisely because Breton did not want to hear about it.” Ruffling feathers was indeed one of his favorite pastimes; he was, in today’s terms, a perfect troll — though trolling does not negate the impact or violence of his sentiments. Combined with his notorious greed and misogyny, he comes across as surprisingly Trumpian.

Should Dreamworld have excluded Dalí’s work? Absolutely not. What’s needed is proper historical context. In many ways, the show suffers from an embarrassment of riches: There are scores of masterworks are on display, but in an attempt to broadly outline a deeply complex, rich movement through overly large categories (for example, most sections' themes boil down to “sex,” “nature,” and “war”) the true power of the work fades into the background. One beautiful section at the end discusses the friendship between Remedios Varo and Leonora Carrington, both based in Mexico, and their shared interest in witchcraft and the occult. On a nearby wall, however, Hebrew characters dance across a painting by Victor Brauner near Kurt Seligmann’s “Flight to the Sabbath” (1956) without even a brief acknowledgement of both artists’ Jewishness and their escapes from the Holocaust. This placement, lacking further information, unintentionally makes the more mystical aspects of their Jewishness appear as just another form of whimsical witchery. And Mexican-born artists — including Frida Kahlo — are folded into a section titled “Exile,” which results in framing Central and South America as simply on the receiving end of Surrealist dreams, rather than a source itself of a distinctive creative force.

I’m glad I saw Dreamworld and basked in the beauty of its art. But I’m also grateful that I learned more on my own time about some of these artists. Because without the whole story, we can lose sight of the difference between those who illustrate monsters — defining them, feeling them, and, critically, fighting them — and those who give in to their horror.

Dreamworld: Surrealism at 100 continues at the Philadelphia Art Museum (2600 Benjamin Franklin Parkway, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) through February 16. The exhibition was curated by Matthew Affron with Danielle Cooke, exhibition assistant.