The Sinister Plan to Demolish a Brutalist Icon in Dallas

Behind the spectacle of City Hall’s potential demolition is the transfer of funding away from the public and into a few extraordinarily wealthy hands.

Dallas City Hall, an iconic Brutalist landmark, faces potential demolition as city officials weigh its future. This fracas shines damning bright lights on the dehumanizing self-interest of Texas “wildcatting” — a regional form of American libertarianism, the noisiest false god of fascism.

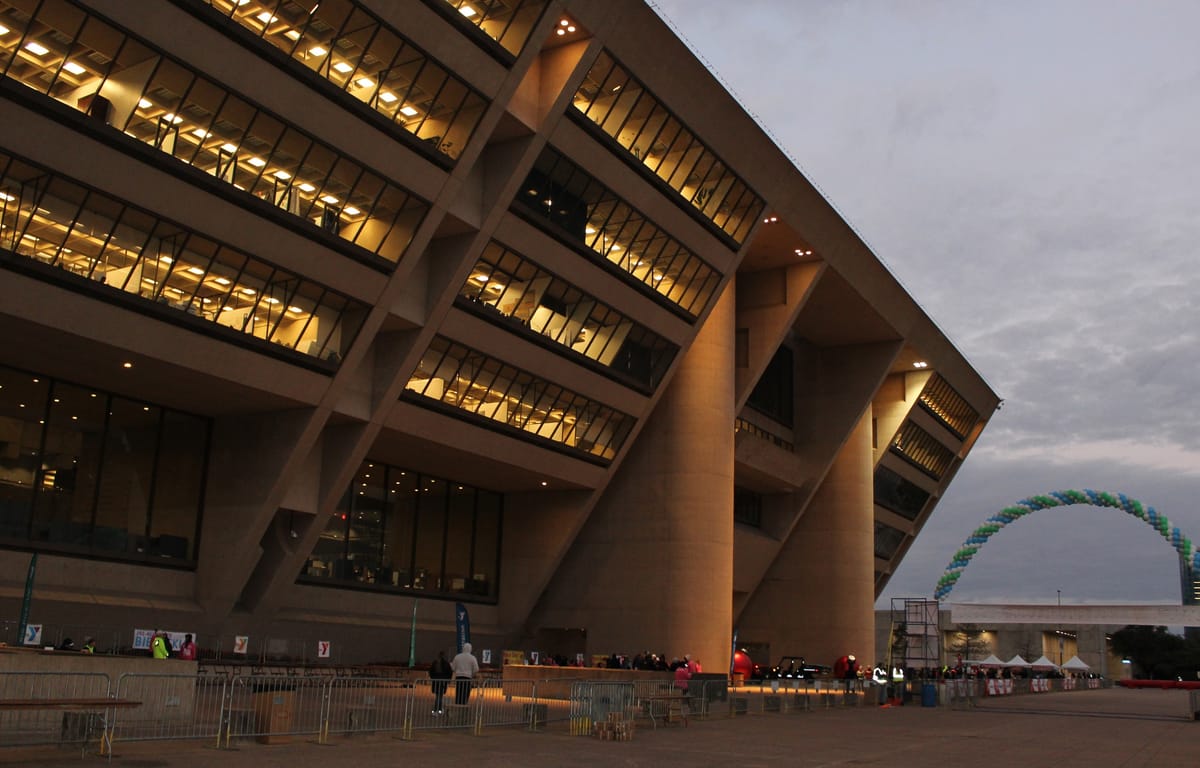

On Wednesday, November 12, all but three of the 15 Dallas City Council members approved exploratory measures for privatizing Dallas City Hall, the public space where they work and where citizens regularly convene. These so-called leaders seek to sell the 11.8-acre community site, demolishing its iconic Brutalist building designed by celebrated architect I.M. Pei and completed in 1978 and a large public plaza with a reflecting pool and sculptures, including Henry Moore’s biomorphic bronze “Three Forms Vertebrae (LH 580a),” or “The Dallas Piece” (1968, cast 1978).

In this proposal, the underground parking garage would likely be preserved to service an arena and casino going up in the City Hall’s place, funded by Las Vegas resident, casino owner, Trump donor, and funder of Texas Republican politicians, Miriam Adelson. The Adelson family owns a majority stake in the city’s basketball team worth $3.5 billion. Adelson supports Texas politicians through direct donations and PACs, backing Republican Governor Greg Abbot and Lieutenant Governor Dan Patrick and Democratic Representative James Talarico, all of whom are tied to her push for casino legalization in Texas.

The smell of corruption is rank. As leaders pander to wealthy donors and ignore regulation and public responsibility, the Dallas-Fort Worth Metroplex faces further real estate overdevelopment on par with the bygone epoch of frenzied mall construction. The American Airlines Center arena, which opened in 2001, stands less than two miles (~3.2 kilometers) away from City Hall. Another stadium is in the offing, proposed by the Las Vegas Sands Corporation on more than 1,000 acres in Irving, where the Texas Stadium once stood. They’ll have a casino, too, if politicians cave to the billionaire class. The 110 empty acres where Valley View Mall stood until 2023 are also ripe for redevelopment.

Democracy dies with the erasure of the public civic realm. This includes taxpayer-supported public services like education, health, science, and infrastructure, such as safe roads, clean water and air, and, notably, cultural institutions, museums, and parks.

Dallas City Hall is a prime example of this. Pei designed the giant inverted pyramid of the building to formally defer to the public sphere. Large, overhanging floors house offices at the top of the building, freeing up public space in the lower floors while creating a slope at a 34-degree angle that functions as a sun break, shading people from the infernal Texas sun. Swiss-French modern architect Le Corbusier pioneered Brutalism and such expressive use of concrete with his Unité d’habitation (1945–52), a prototype for collective living in the air, or a “city in the sky.” Dallas City Hall is the first and most inventive of the five structures that Pei designed in Dallas. It is matched in its beauty and invention only by the last structure Pei designed for the city: the Mort H. Meyerson Symphony Center, the performance hall for the Dallas Symphony Orchestra, completed in 1989. That same year, Pei completed the new entrance to the Louvre in Paris, the iconic glass pyramidal entryway providing scads of natural light to an underground ticket lobby modeled in smooth tan concrete. Dallas City Hall, Meyerson Symphony Center, and the Louvre entrance all speak to Pei’s extraordinary capacity to shape space using various grades of concrete.

Like any building, Dallas City Hall needs regular maintenance. But calls to level rather than renovate or modernize it fit a pattern of malign and willful neglect, followed by attempts to privatize and redevelop other hubs of community in the city. Among these are Reverchon Park and Kalita Humphreys Theater, both historically significant public spaces that had uncertain futures due to disrepair. According to Mark Lamster, Dallas Morning News architecture critic, there are millions of unspent dollars specifically allocated for City Hall’s upkeep that council people have simply not spent over the last decade.

Fascism lives and acts through the political theatrics of destruction, as we witnessed with the recent demolition of the East Wing of the White House to make way for a garish ballroom. Behind the spectacle is the transfer of funding away from the people and public sphere and into a few extraordinarily wealthy hands in the private sphere. Follow the money; this is kleptocracy, a society ruled by people who use their power to steal their country's resources.

To destroy Dallas City Hall is to lay waste to what its visionary modern form embodies. It is a symbol of the golden years of state-led capitalism from 1945 to 1980, in which the country experienced phenomenal growth in wealth and power, borne in part on the institutional redistribution of capital laterally across the citizenry. Under Republican President Dwight D. Eisenhower, top earners in 1953 paid as much as 92% of their income to the government. This is a far cry from economic distribution today. According to the Federal Reserve, the top 1% of the United States population holds $51.8 trillion, while the entire bottom 50% is worth about $4.2 trillion.

The Dallas City Hall building also materializes former Mayor J. Erik Jonsson’s vision for the city as a place of love and innovation, far distinct from the city of hate where former President John F. Kennedy had been assassinated months before Jonsson was sworn in as mayor. Jonsson, who co-founded Texas Instruments and the University of Texas at Dallas (where I teach art history) and ran the city from 1964 to ’71, sought to shape Dallas into an open, generous, and nonjudgmental place that beckons the future through experimental thinking. That ethos is still alive and well among the people of the city, and Pei’s Dallas City Hall is our shared spaceship and better future incarnate.