The Women Weavers of the Little Loomhouse

How did three humble cabins in an old oak forest in Kentucky in 1898 evolve into a thriving textile arts community today?

This article is part of a series focusing on underrepresented craft histories, researched and written by the 2024 Craft Archive Fellows, and organized in collaboration with the Center for Craft.

How did three board-and-batten cabins in the remnants of an old oak forest in South Louisville, Kentucky evolve from a refuge for female creatives in 1898 into a thriving textile arts community today? The tale of the women of the Little Loomhouse is one of strength, connections, and perseverance.

Before the Little Loomhouse even got its name, women like sculptor Enid Yandell, musicologist Mildred Hill, and educator Patty Hill were inspired during visits to their friend and resident painter, Etta Hast, to choose artistic careers over a life of domesticity. Visionary Lou Tate was well aware of this legacy when her parents bought the property for her in 1939. She built upon it by living outside gender norms — she chose a gender-neutral name, and signed correspondences as “Lou Tate,” “Director, Little Loomhouse,” or “Editor, Kentucky Weaver,” with returns addressed to “Sir” — and inspiring generations of crafters in turn.

Born Louisa Tate Bousman in Bowling Green, Kentucky in 1906, Tate earned a bachelor's degree from Berea College. After graduation, her aunt took her to visit an elderly weaver named Nan Owens. Delighted that the young artist would take up the “old art,” as Tate put it in a 1938 book, Owens gifted her five generations of weaving drafts, or instructions for setting up a loom to weave a desired pattern. Inspired and determined to preserve and expand the art, she rode on horseback across the Southern Appalachian region collecting them, which led her to pursue a master's degree in History from the University of Michigan in 1929. She was then sent to teach at the President’s Community School in Madison County, Virginia to pay back her tuition. It was there that she met First Lady Lou Henry Hoover, who gave her the nickname “Lou Tate” and inspired her, via her own work as president of the Girl Scouts, to found the Lou Tate Little Loom in 1936.

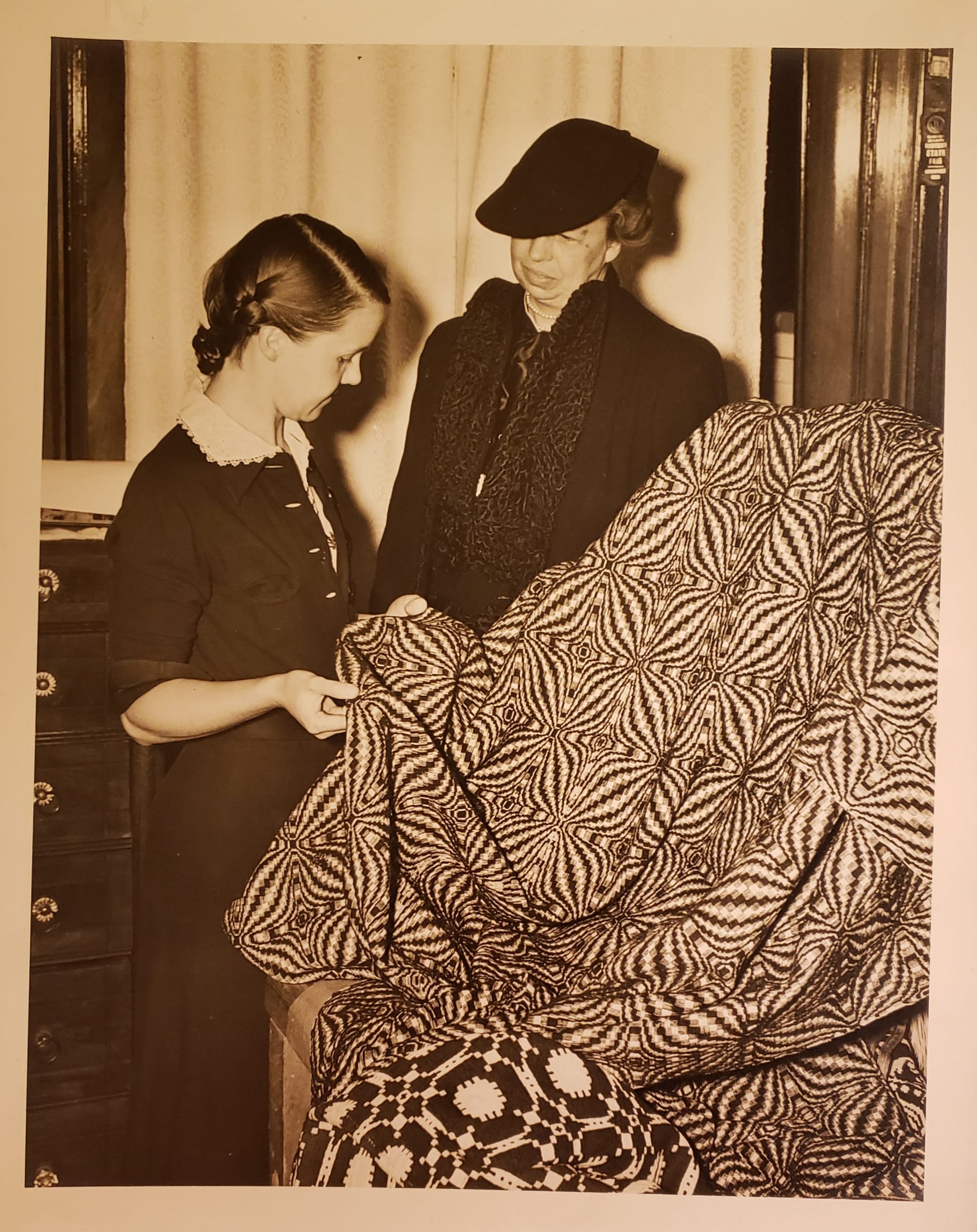

From there, Tate’s reputation grew as both a weaver and textile historian. A custom linens commission from Eleanor Roosevelt led to a visit from the first lady in 1938, which she popularized in her nationally syndicated column, My Day (1935–62). Less than a year later, Roosevelt provided Tate a two-year board and tuition waiver to teach Dorothy Mayor Thompson, a then 18-year-old West Virginian who would go on in the year 2000 to be awarded a National Heritage Fellowship in weaving from the National Endowment of the Arts.

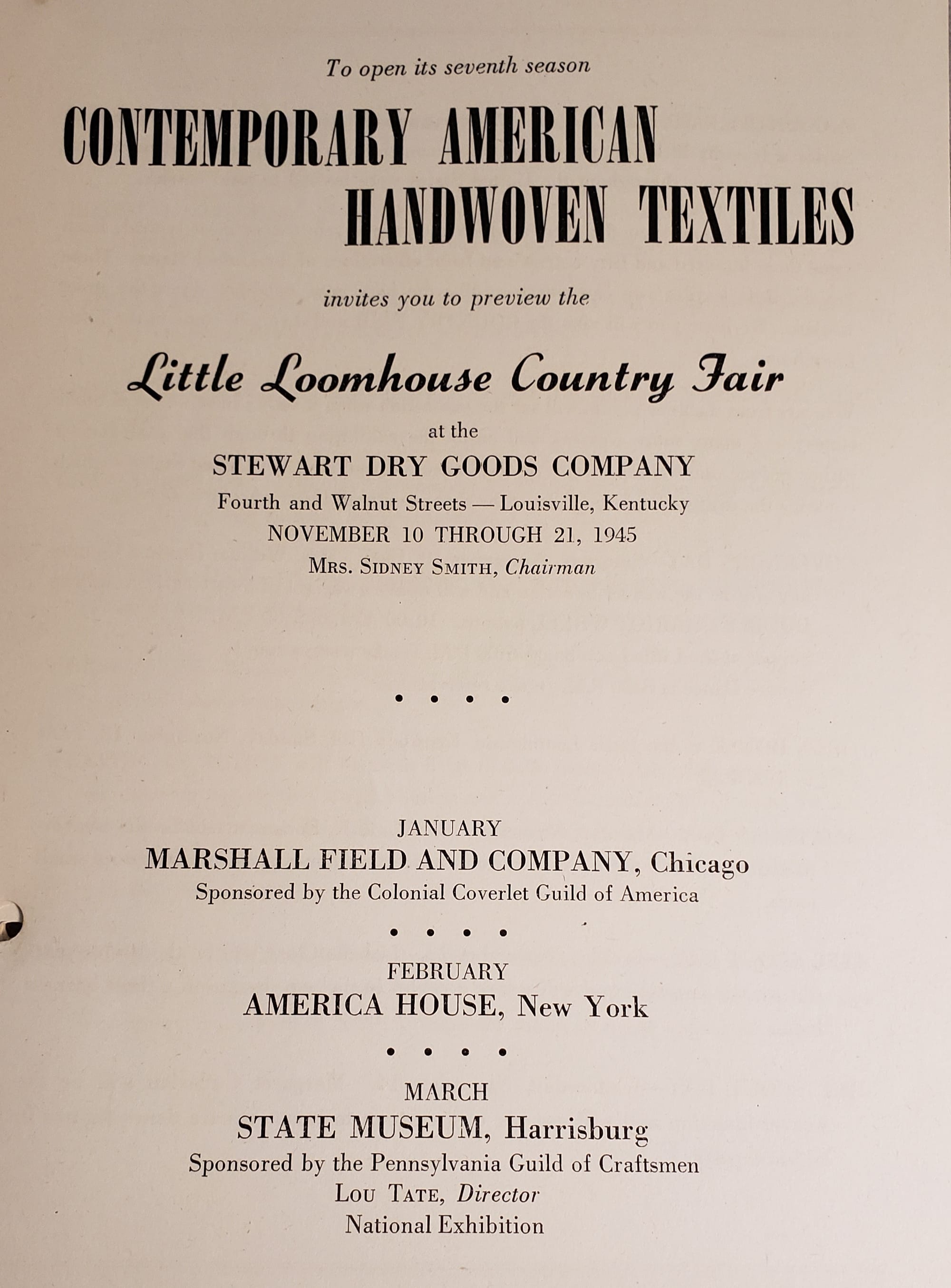

Throughout the early 1940s, Tate advised another notable weaver and textile historian, Marguerite Porter Davison, who published what is considered even now to be the bible of weavers, A Handweaver’s Pattern Book, in 1944. (The Little Loomhouse archives hold over 20 letters that detail the advice and support Tate extended to Davison.) In 1946, Tate curated an annual traveling exhibition, Contemporary American Handwoven Textiles, later named Little Loomhouse Country Fair, shifting focus from production weaving to folk weaving to attract the creative home practitioner. The exhibition would travel from Stewart Dry Goods Company in Louisville to Marshall Field and Company in Chicago to America House in New York and finally to the State Museum, in Harrisburg, Pennsylvania.

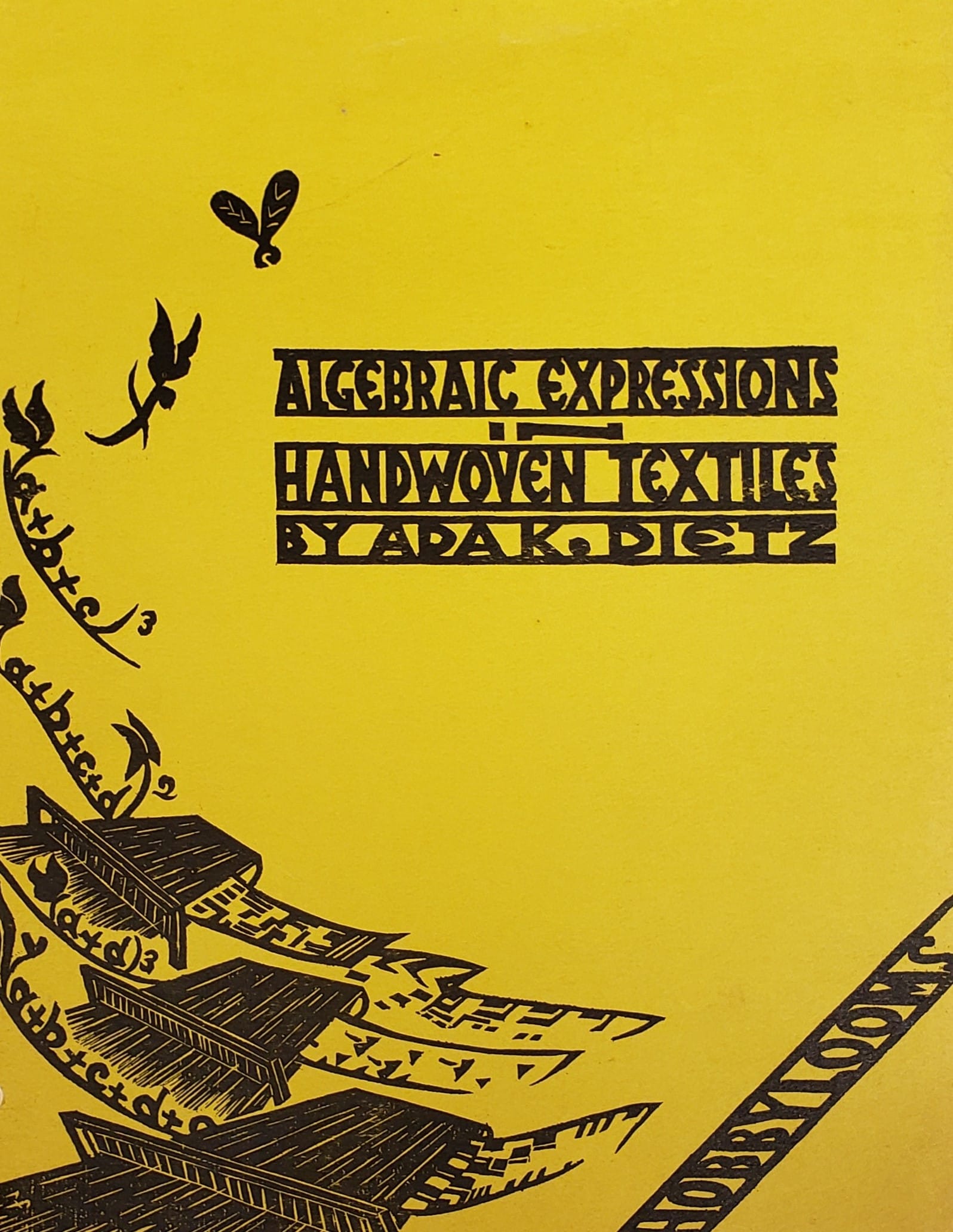

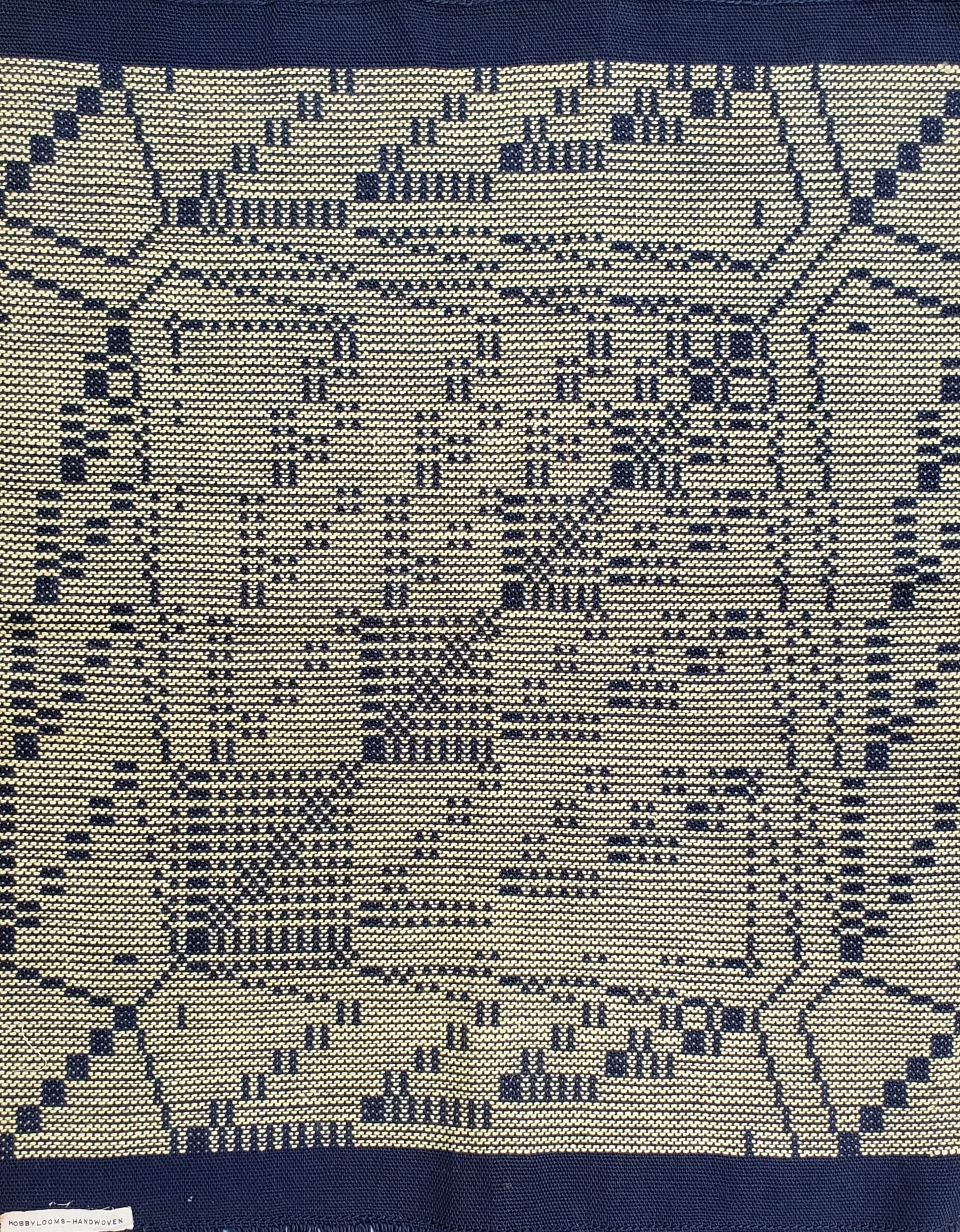

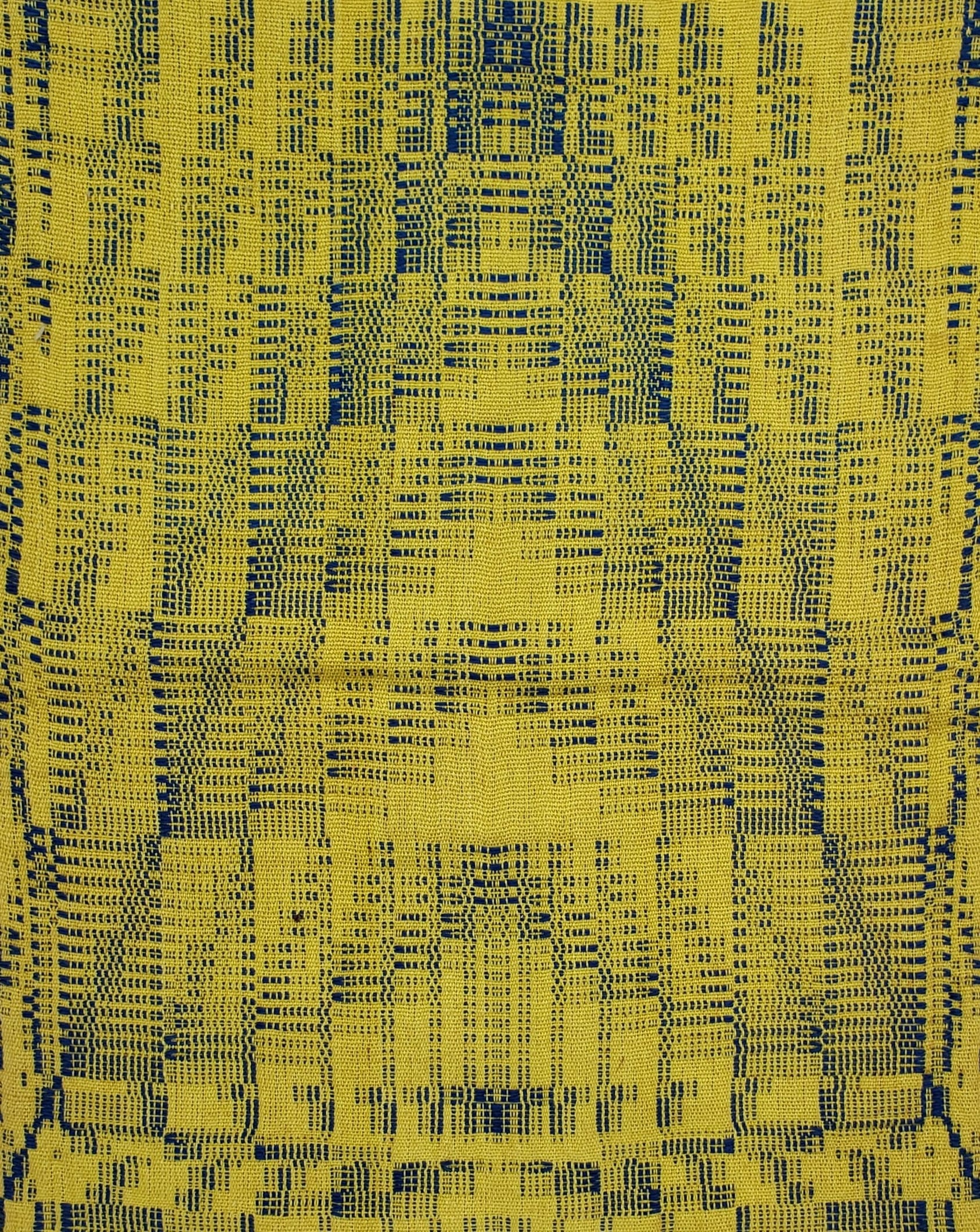

While curating the exhibition — using the title “Lou Tate, Director, National Exhibition” — she learned about experimental weaver Ada K. Dietz and her partner, Ruth Foster. Dietz had been a biology and math teacher when she met Foster, a professional weaver for the Hewson Studios in Los Angeles. Foster inspired Dietz to study weaving at Wayne University under Nellie Sargent Johnson. Afterward, Dietz left Michigan with Foster to live and work, later opening Hobby Looms studio in Long Beach, California. It was Dietz’s novel idea of using algebraic equations to generate weaving patterns that caught the attention of Lou Tate, who invited her to submit work for the 1947 Country Fair exhibition. After working with Dietz the following summer, Tate asked her to assemble study textiles into a draft book. This became Algebraic Expressions in Handwoven Textiles, written by Ada K. Dietz with artistic assistance from Ruth Foster and published, under Tate’s direction, by Little Loomhouse in 1949.

Afterward, Dietz and Foster closed their studio for over a year and moved into a small tagalong trailer with their dog, Pickles, to promote their ideas of using mathematical equations to write weaving drafts. Starting from the Little Loomhouse, they traveled to Michigan, New York, Canada, and Maine, down the coast to Florida, and back across the United States through Texas. In the spring of 1953, an article was published in Handweaver & Craftsman (1950–75) entitled “Two Weavers in a Trailer Spend an Absorbing Year Touring Weaving Centers.” But not all was as successful as the article suggested. A seven-page letter to Tate in June of 1951 explains that when the couple arrived in Michigan, an interview had been arranged with Mrs. Ayres and her photographer from the Detroit Free Press. The reporter, however, completely ignored Foster, who ended up hiding in the trailer. Dietz was understandably upset — they gave a more interesting interview together, and Foster had both encouraged her studies and work and helped her write Algebraic Expressions.

This pattern of denial would continue even within the weaving community. That same year, for instance, the president of the Michigan Weavers’ Guild, Mrs. Weidman, invited Dietz to a meeting. Dietz responded by asking to include Foster, a request to which Mrs. Weidman agreed, asking the pair to meet her outside the dining room. On the day of the meeting, however, Dietz and Foster were left waiting on a couch while Mrs. Weidman was seated inside, ready to eat, a fact they only discovered when a passing guild member asked if they were coming in. “You can imagine how we felt?” Dietz wrote in a June 1951 letter to Tate. “They went in and got her and she was very cordial but no apologies. Had us come in and seated us at another table.” The true nature of the rejection is unclear, but Deitz goes on to write that she did not go on to try to network with other influential figures in Chicago and Detroit, claiming she “didn’t want to force herself or ideas on others.” Thankfully, by then, Algebraic Expressions had already become an inspiration and influence to contemporary American handweaving during the second wave of the Arts and Crafts Revivalist movement.

Algebraic Expressions in particular inspired the creation of the Cross Country Weavers (CCW) in 1957, a group that continues today in the form of an annual sample exchange between 30 geographically diverse weavers. (In addition to this ongoing exchange, two traveling notebooks are archived yearly at the Thousand Islands Arts Center in Clayton, New York and the University of Massachusetts – Dartmouth, and available to the public.) This group was just one of the many ways the Little Loomhouse community expanded: Rose Pero, for instance, was an early CCW member who had studied weaving under Lou Tate in 1940. She would continue to travel and work with her over the next couple decades, and remained in contact with Tate and Deitz until their deaths in 1979 and ’80, respectively.

This sense of community around the Little Loomhouse continues even after the deaths of its individual members. After Deitz passed, for instance, Foster sent Pero the majority of Deitz’s archives. And a few years after Pero’s death in 2000, the man who bought her home brought her things — including Deitz’s archives — back to the Little Loomhouse, where they tell their stories today.