We Must Do More Than Simply Depict Our Lives

The best work in the Bronx Museum’s biennial indicates aspirations beyond this time and place.

In the lobby of the Bronx Museum of the Arts, right before the entrance to Forms of Connection, the seventh edition of the institution’s biennial exhibition, there’s a clutch of three men facing each other, engaged in animated conversation. They don’t move or shift their focus when I approach. They won’t, because they’re life-size figures made of papier-mache, foam, and acrylic paint made by Piero Penizzotto to represent what the show’s curators describe as “people he interacts with in everyday life.”

I also see people like these men — all wearing a version of the urban youth uniform of sneakers, jeans, a hoodie, backpack, and baseball cap — daily. Penizzotto’s “Big Brother Obii Knows Best (Ft. Freddy & Shawn)” (2025) is sincere and earnest in its depiction of people of color (one man is clearly Black, and the others read as ethnically Asian and Latin). Encountering this degree of racial diversity in New York City is typical. But these men don’t often show up in mainstream culture narratives set outside of urban centers unless they are playing gritty “street” characters who are socially disadvantaged or economically underprivileged. I suspect this is part of the reason this work was selected for this show. It is exemplary of an ethos of representing those often described as marginalized — the artist deliberately does not depict the people in everyday life who happen to play chess or badminton or swim competitively or participate in spelling bees.

In a similar vein, Bryan Fernández’s mixed media collage, “Beso a La Cámara” (Kiss the Camera) (2025), depicts an MTA bus, its surveillance cameras multiplied and made conspicuous, and the word “FARE” displayed prominently on its scrolling electronic billboard. The bus is frozen at a stop where a number of people of Asian descent sit with their eyes closed, as if having drifted into sleep. The work gives the viewer a hardscrabble picture of urban life, one where working-class people must contend with a public transportation service portrayed as a rapacious, mercenary enterprise rather than a social service. Here, too, the verisimilitude of the scene is the argument of the work: that it illustrates real lives, lives that tend to be overlooked outside of art centers like the Bronx Museum.

The two previous iterations of the Artist In Marketplace (AIM) Biennial also featured work that sought to visualize groups underrepresented in mainstream culture, more or less via a strategy of mimesis. And I have encountered these kinds of depictions not only in this museum, but throughout the contemporary art scene — work that conveys an implicit expectation that the viewer will be moved by the authenticity of its presentation. But this genre of art reads to me as overly sentimental, and tends to conflate the urban with the underclass — not the same social group, though they often overlap. This kind of art is usually also relatively simple in its aesthetic construction, and hammers the same emotional registers over and over again. It feels somewhat awkward or perilous to call out this work as stagnant and simplistic because I support the effort to spotlight underrepresented perspectives. But elsewhere in the exhibition, there are artists who hold similar values but also innovatively transform the materials they work with. Thus, they give us an elsewhere to imagine.

Take Jordan Corine Cruz’s “Opportunity for Stillness” (2025), a public park bench reprised in red votive candle wax. Its shape is taken from urban reality: three sets of legs supporting a backrest and seat. These slabs undulate like a wave, intimating that the structure is more fragile than expected, made of substance that accompanies spiritual petitions where no human being can follow. Or think of Katie Chin’s “Short Pay, Short Shovels” (2026) which features several metal handles attached to gnarled and twisted tree branches that end in ceramic shovel blades, presented atop a bed of gravel and random metal spikes. The wall text tells us that it is inspired by a legend about a group of railroad workers who shortened their shovels as an act of understated resistance. In a similar vein, Jodie Lyn-Kee-Chow’s “Valor and Revolt” (2024–26) proffers a collection of ceramic versions of bladed and defensive weaponry including machetes, axes, arrows, and shields — the tools of armed revolt. But she has transformed them into trophy pieces, as if to suggest that the battles have already been fought and won, and the tools of struggle have now become merely symbolic.

In each case, the stuff of real life is transformed into some other material that indicates aspirations beyond this time and place. In other words, these works are not about giving the viewer a picture of our current circumstances, but a glimpse into what might exist beyond them. Thus, Cruz gives us a bench that won’t hold our weight, so we (those of us who can) may have to learn to spiritually stand without inherited support. Chin’s work uses metaphor to suggest that the peculiarity, eccentricity, and unpredictability we see in nature also exists in humans, and the tools of industry and industrial operations can be foiled by our unpredictability. And Lyn-Kee-Chow demonstrates that sometimes, what we have previously experienced as violence might be rendered in symbolic terms and therefore stripped of its destructiveness. It is a picture of what one’s life might look like when you have overcome.

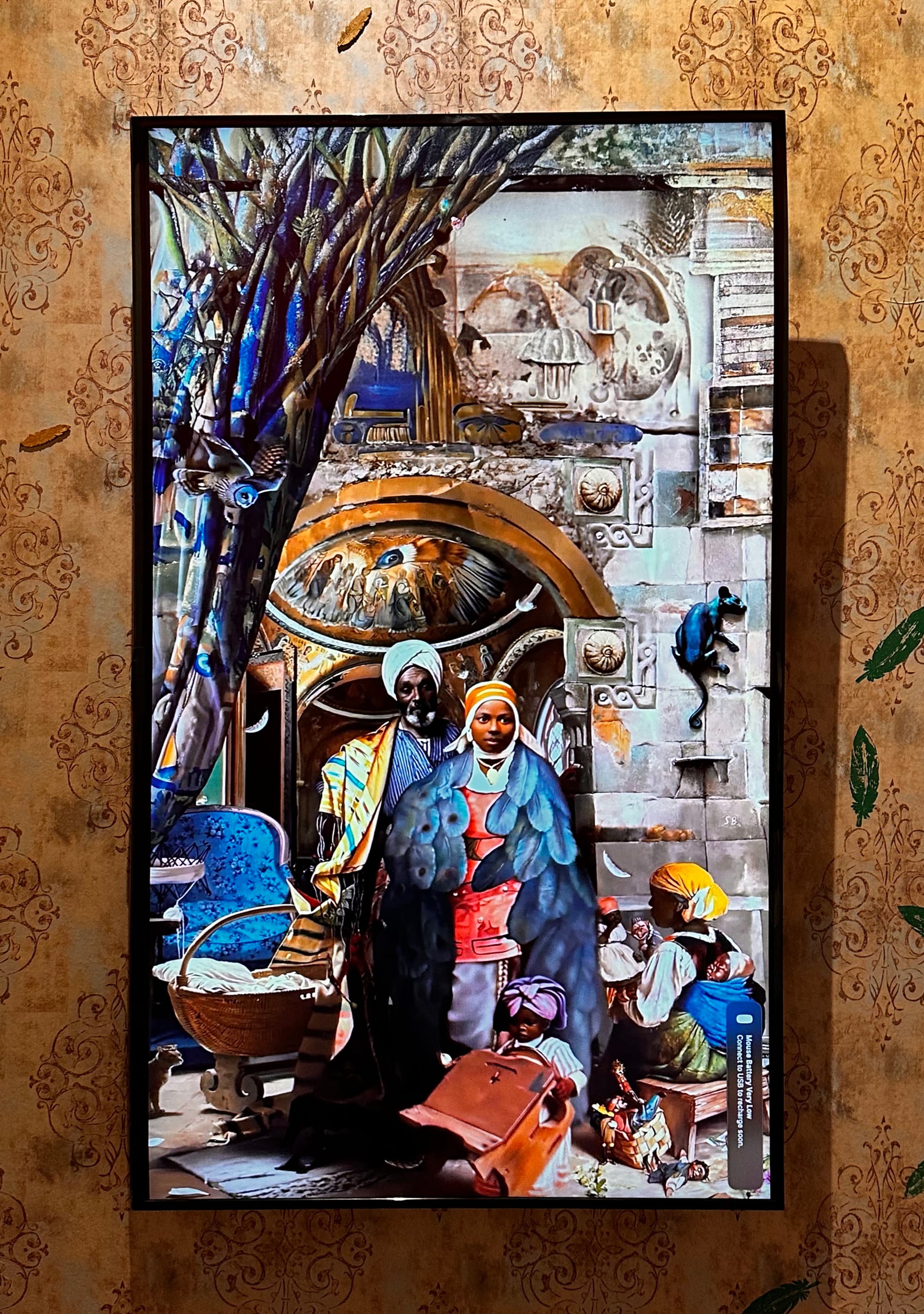

Another brilliant piece in the show is DeepPond Kim’s “Veil” (2022) which depicts a face that has been transformed into a façade of elegantly patterned ceramic breeze block — a “veil” that is almost indistinguishable from that which it is intended to hide. The work proposes a new framework for considering debates about the agency of Muslim women who wear veils, suggesting that the face itself may operate as another kind of concealment. Also worth mentioning is Skip Brea’s “The Gaze” (2022–24), which consists of a digital screen on which a seemingly static courtly painting of a Black family abruptly comes to life. Here, a sumptuously dressed man, woman, and small children are placed in a lavishly appointed interior featuring a gilded archway and ceiling fresco. The family looks out in the direction of the viewer, and then, at some hidden signal, walks out of the picture plane, before reentering it from the background to take up their positions again, as if to say that this moment of wealth and dignity for people of color will persist or recur.

In the AIM biennial and more generally throughout the art scene, this is the kind of work that I yearn to be exhibited more often: artwork that looks toward a horizon that expands rather than stands still. We deserve a vision of something that’s beyond this time and place.

The Seventh AIM Biennial: Forms of Connection continues at the Bronx Museum of the Arts (1040 Grand Concourse, Concourse, Bronx) through June 29. The exhibition was curated by Patrick Rowe and Nell Klugman.