What Happens When a Museum Gives Away Art for Free?

Take Me (I’m Yours) is a re-staging of a show that first appeared at the Serpentine Gallery in 1995, when it was conceived of by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Christian Boltanski. In this 2016 New York edition, curators Obrist and Jens Hoffmann feature more works by 42 artists.

At the Jewish Museum last Sunday, a little girl wearing a pink hair bow ran around dropping pieces from various installations into a paper bag: A seltzer can printed with a drawing of lemons, designed by artist Adriana Martinez; a gelatin pill capsule, from “Pill Clock,” by Carsten Holler; hard candies in shiny red, white, and blue wrappers, from the installation “Untitled” (USA Today),” by Felix Gonzales-Torres. She took these things with frantic excitement, after barely looking at them, like she was at a competitive Easter egg hunt. A woman who might’ve been her grandmother told her to slow down, but no museum guards scolded her. In the exhibit Take Me (I’m Yours) (which Hyperallergic previously visited in Paris), what’s usually considered the ultimate art museum crime — taking the art home with you — is not just allowed, but encouraged.

Take Me (I’m Yours) is a re-staging of a show that first appeared at the Serpentine Gallery in 1995, when it was conceived of by curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and artist Christian Boltanski. The works on view, by 12 artists, all doubled as utilitarian or decorative objects. As an upending of museum conventions, visitors were invited to touch, test, or take the objects home with them.

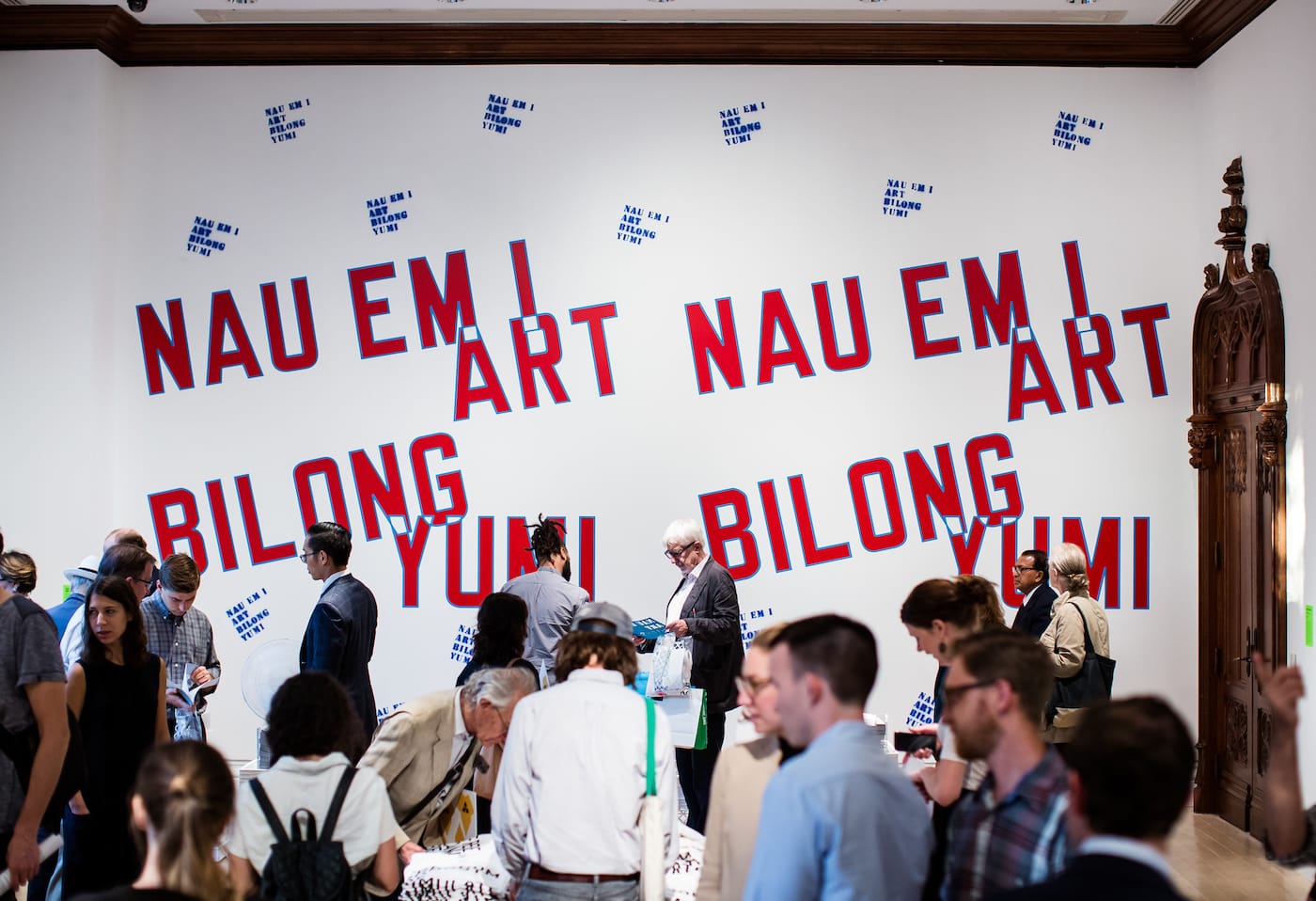

In this 2016 New York edition, curators Obrist and Jens Hoffmann feature more works by 42 artists, many of them affiliated with or inspired by the Fluxus movement. (Some, including London duo Gilbert & George, Lawrence Weiner, and Carsten Holler, were part of the show’s original cast.) Brown paper bags are dispensed at the gallery’s entrance; visitors, invited to fill them up with loot, become novice art collectors.

Adorn your lapel with one of Gilbert & George’s buttons, with slogans like “God Save the Queen” and “Decriminalize Sex,” which are part of a series of works called THE BANNERS. Slip on an old sweatshirt from Christian Boltanski’s “Dispersion,” a pile of used clothes in the center of the gallery that could’ve come from a Salvation Army dollar bin. And if you’ve ever feared pulling a Mr. Bean and sneezing on a $1 million painting at some serious, silent museum, here it’s the opposite, as Haim Steinbach’s “Tissues” is a sculpture of a fully stocked tissue box. (You can even keep the tissue!)

Free art is so rare in a capitalist society — especially at a Fifth Avenue art museum — that the show’s premise alone feels novel. While walking around the gallery’s hardwood floors and pocketing things, you half-expect an alarm to go off. Take Me I’m Yours is a miniature experiment in value distribution, one that imagines what a more democratic art system might look like. (Martha Rosler nods to this aspect of the show in“Free Gift!,” a series of double-sided inkjet prints that pair advertising photos with excerpts from Karl Marx’s Capital, a somewhat heavy-handed comment on consumerism.) Even part of the exhibit’s funding relied on sharing and donation (of course, all this free stuff wasn’t free): In order to keep the show fully stocked, the Jewish Museum crowdfunded more than $30,000 via a Kickstarter campaign — and additional funding came from corporations like AIG Private Client Group and Bloomberg Philanthropies.

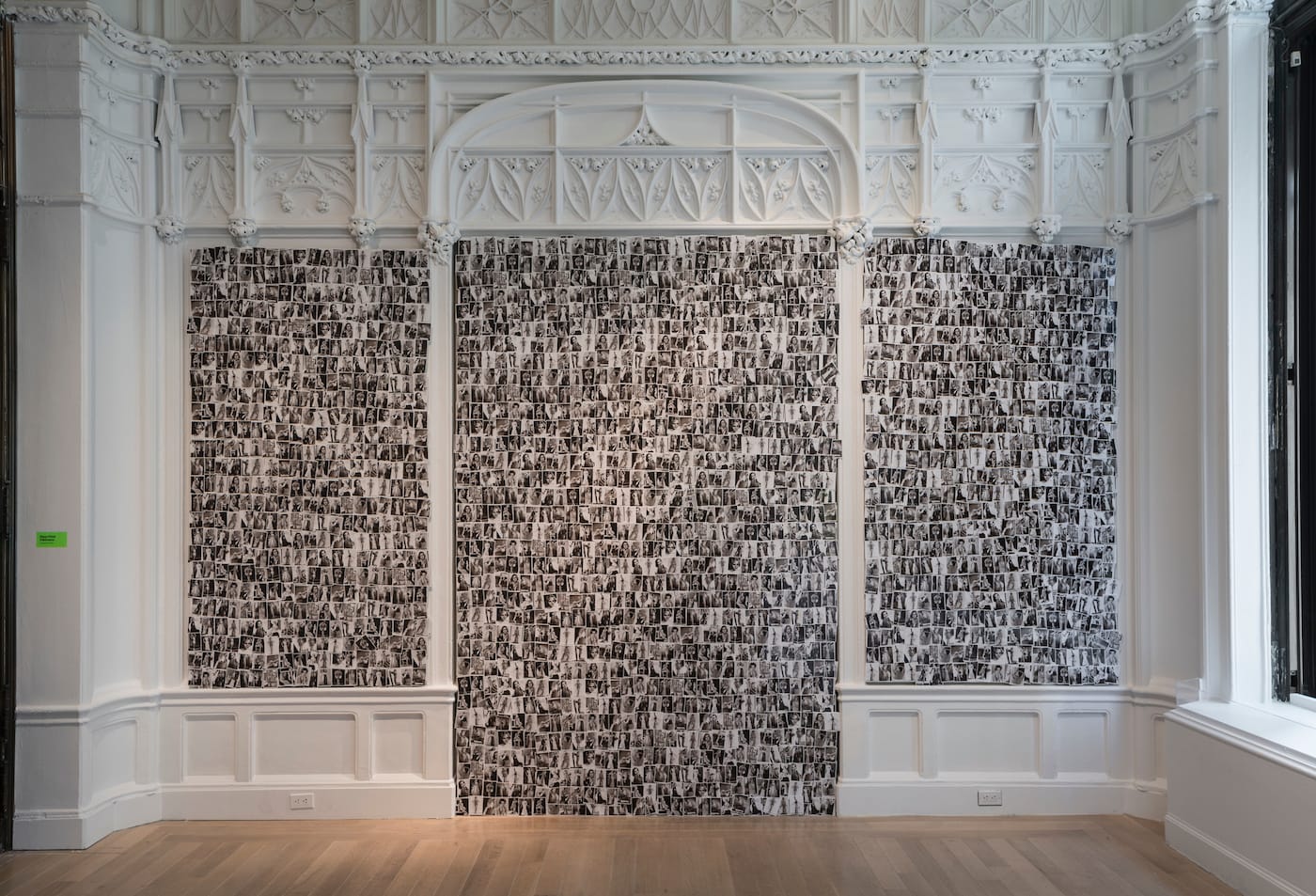

Most of the works on view are not as exciting visually as they are conceptually. At times, the exhibit feels like a blowout sale at a museum gift store filled with arty souvenirs. Quality had to be sacrificed for quantity: more than 400,000 individual objects were produced for the show. Yoko Ono’s “Air Dispensers” consists of plastic capsules of, yes, air in 25 cent-machines; Alex Israel’s “Self-Portrait (Lapel Pin)” is a container full of shamelessly self-promotional enamel pins depicting the artist’s face.

Romanian artist Daniel Spoerri’s “Eat Art Happening” avoids this mass-produced object formula. It’s a startling sculpture of a human skeleton made from sugar paste, lying on a bed of brown sugar in a crypt-like closet space. At the end of the show, museum visitors will eat the sugar skeleton, along with a bunch of small winged sugar phalluses.

Carsten Holler’s “Pill Clock,” which drops a red-and-white placebo pill onto the floor every three minutes, evokes Alice in Big Pharma Wonderland: visitors are invited to swallow the pill, or not. Holler, a former entomologists who studied insect behavior, treats the work as a pseudo-scientific experiment, asking why some visitors swallow the pill and others don’t.

Watching how people approach the artworks in Take Me (I’m Yours) is sometimes more interesting than the actual artworks. In some visitors, like the little girl in the pink hairbow and also, me, the show activated a long-repressed urge to take things without asking and without paying for them. It felt an art museum version of The Purge, a dystopian horror film in which all criminal activity is legal for 12 hours a year.

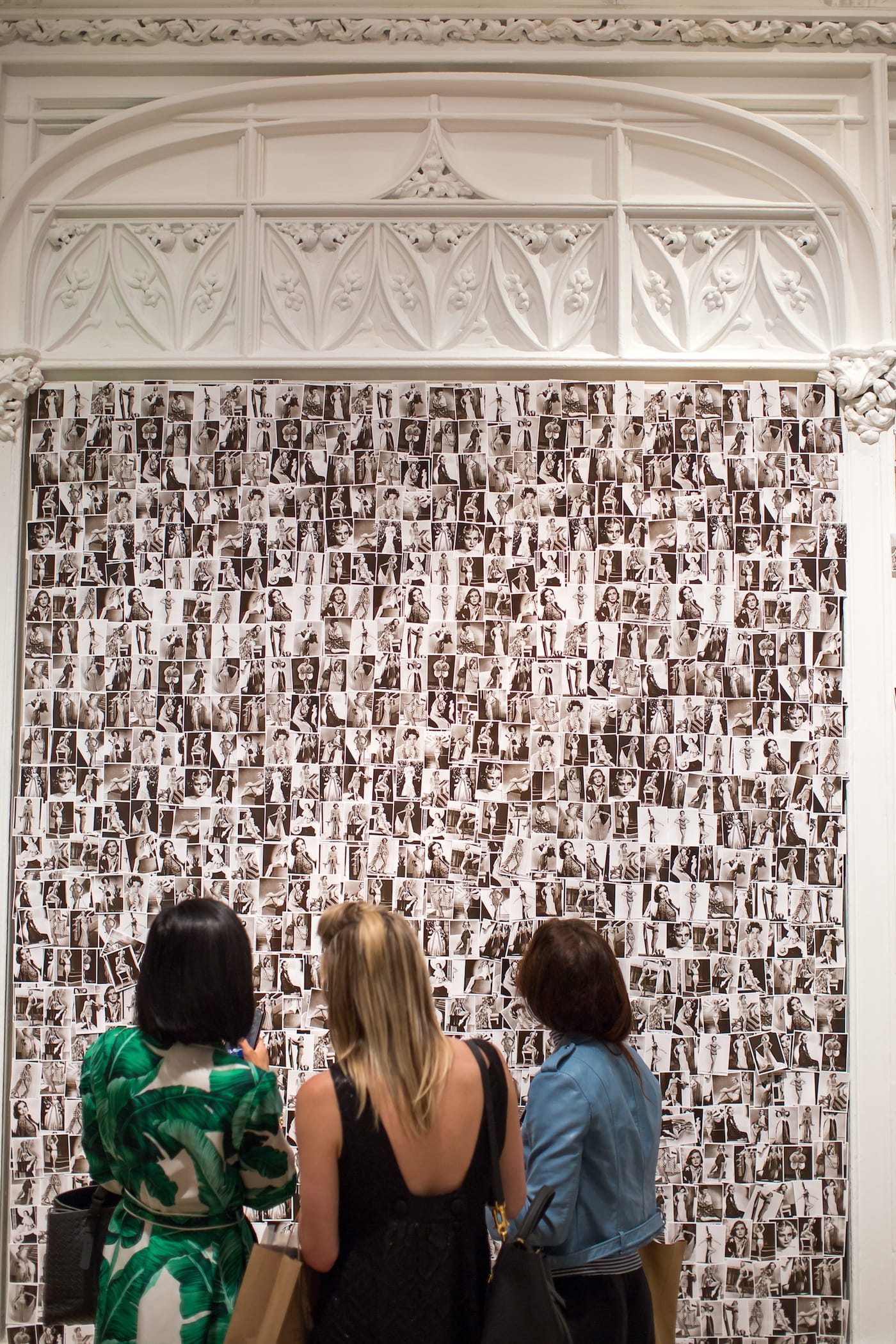

I walked out of the museum with a plastic bag filled with random stuff made by famous artists: a tiny round clear plastic container (Yoko Ono); a pin that said “God Save the Queen” (Gilbert and George); a long orange ribbon that says “Dignity and a Living Wage” (Andrea Bowers); a fabric patch stitched with the word “NEGATIVE”; three black-and-white photos of 1940s pin-up girls (Hans-Peter Feldmann); a silver can of seltzer printed with a drawing of lemons (Adriana Martinez); a t-shirt that said “Freedom Cannot Be Simulated” (Rirkrit Tiravanija); and a black paper square (Heman Chong).

Someday, fingers crossed, this free “art” will become very valuable and I can sell it on eBay for lots of money.

Take Me (I’m Yours) continues at the Jewish Museum (1109 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) until January 7, 2017.