When Artists Lose Their Archives

I couldn't afford my storage unit anymore. After it was auctioned off, I found out that parts of my lost work were being sold online.

There is a particular kind of shame that comes with losing your own work.

Not the spectacular kind. Not the kind that arrives with a public failure or a dramatic ending. This shame is quieter. It settles in the body. It convinces you not to tell anyone. It suggests that if you were more responsible, more successful, more organized, this would not have happened. It tells you that asking for help would only confirm what you already fear, that you were never supposed to need it in the first place.

Years ago, I couldn’t afford the payment on a storage unit in the neighborhood of Greenpoint in north Brooklyn, where I had been keeping a large portion of my work. Sculptural components, unfinished pieces, modular elements, things that only made sense in relation to one another. The unit was auctioned off. There was no intervention, no warning. The archive simply changed hands.

About a year later, a friend sent me an Instagram post and asked, almost casually, if the work in the background was mine. I recognized it immediately. Pieces from that storage unit were staged as interior décor by a Philadelphia-based vintage design shop. When I looked further, I found multiple posts offering parts of the work for sale. Not complete pieces, but components of singular works. Individual elements were photographed, priced, and listed under my name without tagging or contacting me. At the time, I had no idea this was happening. Parts of my practice were being dismantled, circulated, and monetized without my knowledge, their meaning flattened into décor.

This was not just the loss of objects. It was the loss of authorship, sequencing, and context. Works that were never meant to exist independently were broken apart and reintroduced to the world as aesthetic fragments. My archive had become modular in the most violent sense. Not by choice, but by necessity and market indifference.

In Archive Fever, Jacques Derrida describes the archive not as a neutral container, but as a site of authority, anxiety, and exclusion. The archive is never just about preservation. It is about who gets to decide what is kept, how it is ordered, and who has access to it. Losing control of my work was not only a material loss. It was a loss of archival authority. A reminder that preservation is always entangled with power, and that power rarely rests with the artist once the work leaves their hands.

Artists are rarely taught how to talk about this. We are trained to see our studios as sacred spaces and our archives as extensions of ourselves. What we are not given are the material conditions to protect them. Storage, when you are living project to project, grant to grant, becomes a ticking clock. Miss one payment and the evidence of your labor is no longer yours.

Public storage is sold as neutral infrastructure, a convenience. For artists, it is often a site of profound vulnerability. These spaces are subject to floods, fires, mold, theft, rodents, and power failures. They are not designed to preserve culture. They are designed to extract monthly fees. The longer you stay solvent, the longer your work survives. The moment you falter, the archive becomes disposable.

In September of last year, a fire tore through an iconic artist studio building in Brooklyn, destroying decades of work in a matter of hours. Studios that had housed entire careers were reduced to debris overnight. The loss was not abstract. It was total. What that fire made visible was not only the fragility of materials, but the absence of meaningful infrastructure to protect artists’ archives before catastrophe strikes. Disaster does not discriminate, but its consequences do. Artists without generational wealth, without secondary storage, without institutional backing are always the most exposed. That fire was not an anomaly. It was part of a longer pattern of loss that artists have been absorbing quietly for years.

One of the structural conditions that makes archival precarity so acute is the constant threat of environmental disaster. Storms, floods, fires, and other climate events can erase entire bodies of work in a matter of hours. After Hurricane Sandy, galleries in Chelsea were still recovering years later, with basement studios, storage spaces, and ground-floor archives damaged or destroyed by floodwaters that swept through downtown Manhattan. More than a decade on, the scars of that event are still felt, not only in the work that was lost, but in the ways artists and institutions continue to relate to space, risk, and memory. Dealers and artists alike were left to rebuild what had been made vulnerable by an infrastructure that placed cultural material below flood lines and away from meaningful protection. The question that lingered was not only financial but existential. How do you reconstruct the thread of a practice when its physical record has been submerged? This history is not distant. It is a reminder that the systems surrounding art storage and display remain brittle in the face of storms that climate scientists now tell us are worsening, and that preservation in the arts is still treated as an individual responsibility rather than a shared obligation.

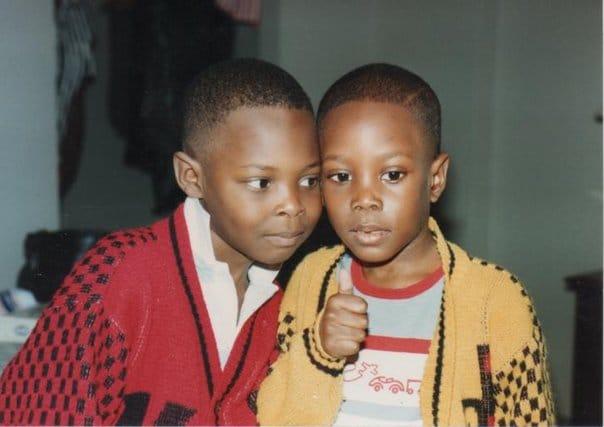

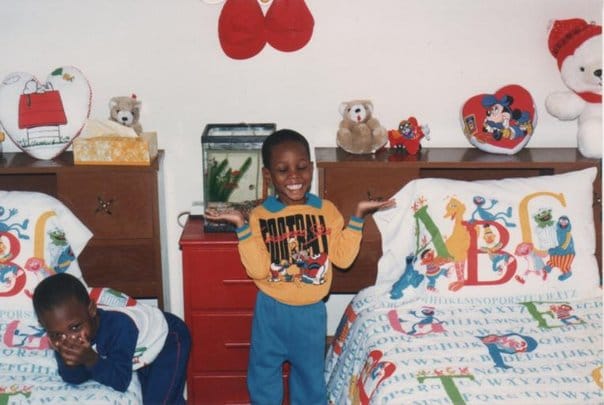

One of the works that was broken apart and sold off from my storage unit had been part of my exhibition For Demetrius at the Sugar Hill Children’s Museum in 2019. The show was named for my late brother, who died from sickle cell disease in 2009, and it marked the tenth anniversary of his passing. That work was never meant to circulate casually. It was an act of remembrance, a way of holding grief in form. Knowing that it had been dismantled and redistributed without context was emotionally devastating in a way that is difficult to explain. It felt like a second loss, quieter than the first, but no less final.

Recently, news circulated about a breakthrough gene therapy that has effectively cured sickle cell disease in at least one patient. I read it with a complicated mix of relief and grief. Scientific progress arrived too late to change my brother’s life, just as recognition arrived too late to protect the work that bore his name. These timelines do not align. They rarely do. What remains is the knowledge that some forms of care only appear after loss has already done its work.

What connects the storage unit, the fire, and the auction is not just money. It is performance. Artists are expected to perform being okay when they often are not. The art world rewards the appearance of stability. It punishes visible need.

In my previous writing about art auctions, I was thinking about spectacle. About how auctions stage confidence, inevitability, and demand. How value is performed in real time, with no room for hesitation. What becomes clearer here is the psychic toll of that performance. Auctions teach us that worth must never waver. The hammer comes down. The price is set. Everyone pretends this outcome was natural.

Shame enters when an artist’s reality cannot sustain that fiction.

There is shame in admitting you cannot afford storage. Shame in saying you missed a payment. Shame in asking for help before the crisis becomes irreversible. Shame in revealing that the archive, the thing institutions later rely on to narrate your significance, is one accident away from disappearance. This shame is not incidental. It is structural. It keeps artists performing competence while absorbing risk privately.

Artists learn early how to be okay. We learn how to downplay instability. We learn how to smile through precarity. We learn how to turn survival into narrative resilience. What we do not learn is how to ask for help without fear of being seen as unprofessional or unviable. Silence feels safer, even when it isn’t. What often goes unacknowledged is that these moments do not end when the immediate crisis passes. Like storms or fires, they leave scars that shape how artists move through the world long after the damage is no longer visible.

The auction clarifies the asymmetry. When work appears at auction, it is framed as success regardless of whether the artist benefits. When work is lost through a storage auction, it is framed as personal failure. Both are auctions. Only one is allowed to confer legitimacy. The other produces silence.

This is why shame becomes part of the archive. Not just the shame of losing work, but the shame of nearly losing it. The shame of hiding instability. The shame of knowing the system prefers artists who can absorb risk quietly. These residues accumulate alongside objects, sketches, files, and fragments. They shape what artists keep, what they discard, and what they stop trusting themselves to hold.

In this sense, the precarious archive is not only material. It is psychological. It is the ongoing labor of maintaining the appearance of being okay long enough for the market to catch up, or for institutions to intervene, or for history to decide you were worth preserving. When that performance fails, the consequences are real.

If the archive is precarious, survival cannot be an individual project. Fred Moten, writing with Stefano Harney in The Undercommons, offers language for thinking about life and labor outside institutional recognition. The undercommons names the informal, relational networks people build when official structures fail them. For many artists, this is already how preservation works, through shared storage, borrowed space, mutual aid, and artist-run experiments that refuse the logic of scarcity.

There are no perfect solutions, only survival strategies. Some artists digitize aggressively. Some make rules about what must remain intact and what can be released. Some negotiate storage with galleries or collectors. Some rely on friends, informal networks, or shared spaces. Writing becomes an archive too, a way of preserving intention when material evidence is unstable.

None of this erases the underlying problem. It names it. The precarious archive is not an anomaly. It is a condition of contemporary artistic life. It asks artists to imagine a future audience while living in a present that offers very little security.

To name this is not to confess failure. It is to refuse the lie that artists are solely responsible for their own erasure. The archive is not just a personal burden. It is a cultural infrastructure. If we care about artists’ legacies, we have to care about the conditions under which those legacies are allowed to survive, long before the market decides they matter.

For now, many artists continue to work knowing their archives exist on borrowed time. One missed payment. One storm. One fire. The work persists anyway, not because the system protects it, but because artists keep making it.

That endurance deserves more than silence.