When the Language Meant to Prop Up Art Makes It Fall Over

In Practice: Material Deviance, the group exhibition currently occupying the quirky basement space at SculptureCenter, can't quite live up to its curatorial statement.

It is often self-evident that the language used in an exhibition press release outstrips the promise and potential of the visual art associated with it. Galleries and museums regularly use releases to write checks that the work itself can’t cash. In the case of the exhibition In Practice: Material Deviance at SculptureCenter in Long Island City, the release actually gets at one of the chief ways in which the work here founders.

The release states that the artists are “pointing to the ways that things — like bodies — manage to exceed and even disrupt the systems that attempt to contain them.” The work may want to do this — that is, disrupt the architectural system that contains it — but doesn’t quite muster up the wherewithal to do so. SculptureCenter, a former trolley repair facility, is a captivating space. Its ground floor has the sort of regulation white cube accoutrements of concrete floors and resolutely colorless (or brick) walls, but in the basement, where this exhibition is on view, things get kinda weird. There are cup-like dead ends, narrow corridors, and recesses in the walls for machinery that is no longer present, all of which constitute a maze of passageways that make this space feel like I might stumble upon a door that opens onto Narnia.

Much of the work in Material Deviance, especially the slide and video pieces, feels unambitious and uninspiring stuck in little cupolas and rooms, and thus dies on the vine. Olivia Booth’s series of peculiar, lit agglomerations of glass and metal installed along a passageway is visually provocative, but strange in the way that feels like Booth read about how to make inscrutable art in a book. I get a similar vibe from the “Temporary Walls” (2017) installation by Lauren Bakst and Yuri Masnyj, which features dark, organically shaped rocks interspersed around what could be a living room full of modernist tchotchkes with clean lines including books and a stereo. This might be the vision of a futuristic space where the rocks serve some non-obvious function, but mostly their placement seems arbitrary in a way that doesn’t let on to any deeper meaning or visual seduction.

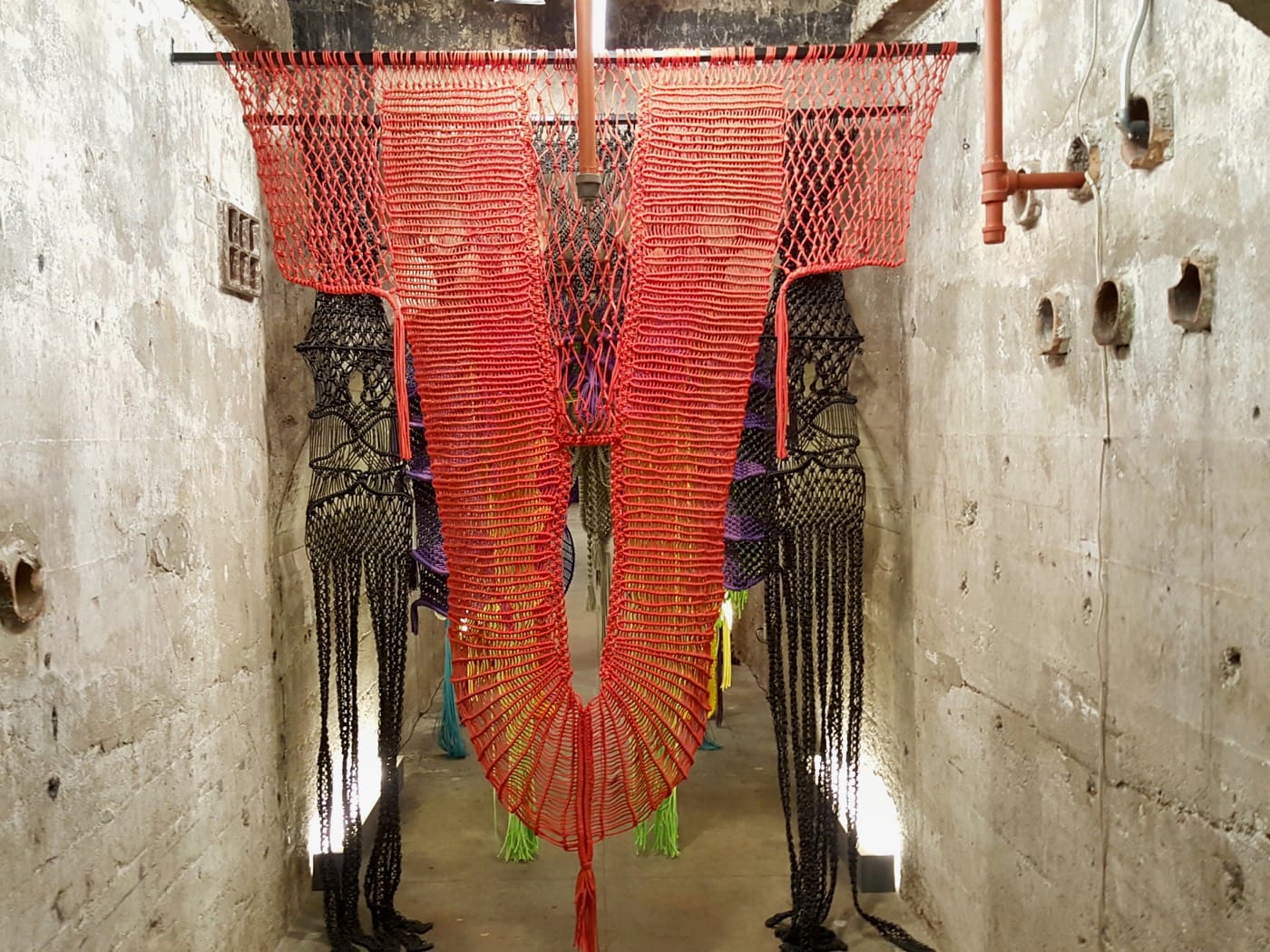

Again, according to the press release, the artists selected by curator Alexis Wilkinson “look to irregularities, glitches, gaps, residues, and altered states — either found or enacted — as a means of accessing the latent histories of materials in order to expose underlying systems of power, regulation, value, and control.” However, I don’t see the exposure of these “underlying systems.” I do witness a kind of astuteness about materials in Jesse Harrod’s “Taught tight tender sway” (2017), which uses macramé to symbiotically interact with the space and transform an almost impassable hallway into something resembling the enfilade for a kind of coronation ceremony. This is my favorite work in the show. One piece that holds its own meaning independent of the space is Barb Smith’s “Untitled” (2017), made of memory foam and aqua-resin. It looks like a hand-made form that was bent, prodded, and poked into its shape, a vaguely menacing sock puppet able to stand up for itself.

Admittedly, to present work outside of any kind of rhetorical framework would cause many viewers to struggle with such a varied exhibition. But looking at this show I wonder whether the language used here could have been more humble, situating the work where it can be recognized, but not placing it on a pedestal from which it is likely to fall.

In Practice: Material Deviance at SculptureCenter (44-19 Purves Street, Long Island City, Queens) continues through March 27.