When We Crave the Story More than the Artist

The play Master invents an artist and reveals him to the audience through voicemail messages, eulogies, artifacts, and pieces of his magnum opus.

A succession of 20th-century artists has conditioned audiences to value persona as much as, if not more than, an artist’s actual work. Andy Warhol, Jackson Pollock, Jean-Michel Basquiat, and Tracey Emin come to mind. They and others like them, plus a supporting cast of writers and dealers, have promoted the notion that bits and pieces of remembered or invented lore — especially salacious and intimate details involving sexuality, romance, family relationships, drug or alcohol abuse — generate the artist’s status, alongside exhibitions and artwork. The play Master, written by W. David Hancock with artist Wardell Milan and now playing at Irondale Theatre Center, where it’s produced by the Foundry Theatre, implies that this development has reached an inflection point: now, if we are given the stories, the signs and traces of artistic output, we don’t really need the artist anymore.

Master dramatizes the current state of play in the art world (but the lessons carry over to other arenas of culture, like sports), demonstrating not just that we privilege the individual personality too much; rather, we don’t know how to look at art without leaning on that crutch. It makes this argument by completely inventing an artist, James Leroy “Uncle Jimmy” Clemens, and revealing him to the audience through the appurtenances of voicemail messages, eulogies, ceremonies, artifacts from the places he lived, and pieces of his magnum opus: “The Illuminated Twain,” a multifaceted, bricolage work that’s a response to Mark Twain’s The Adventures of Huckleberry Finn undergirded by anger and bitterness.

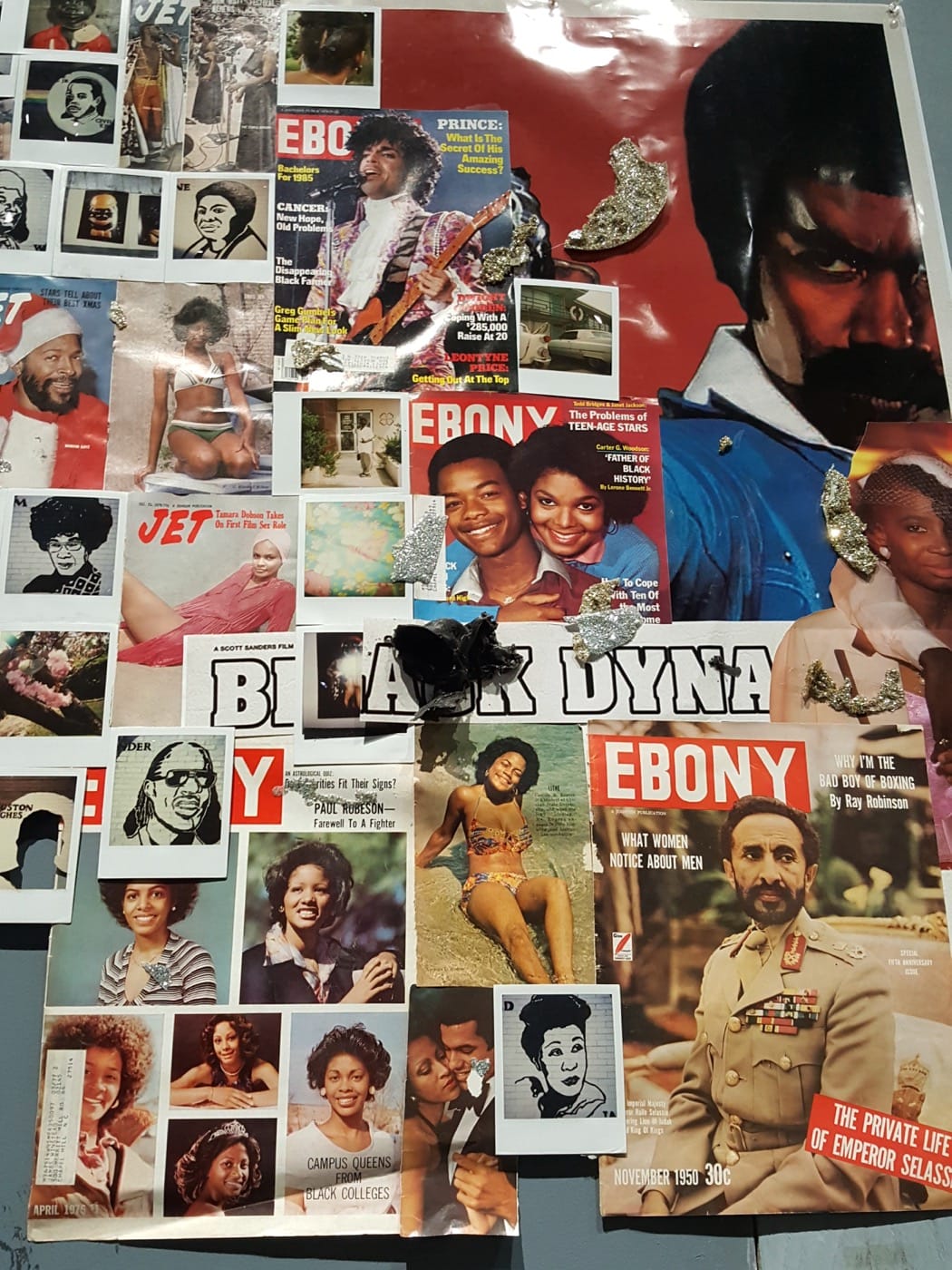

Everything about this setup is clever, particularly the creation of a gallery filled with objects from the “Illuminated Twain.” The audience is allotted about 20 minutes to explore the exhibition before the performance begins. Among the collages and magazines, voice recordings, and abstract sculpture, I linger inside a shed with a stuffed dummy with one white, right hand as rap music plays. Other fascinating pieces include a series of what look like antique photographs, whose caption explains they are “Jim’s extended family, thousands of souls that Twain refused to mention”; a teepee made of men’s shirts; and a table covered with artifacts rescued from Clemens’s studio.

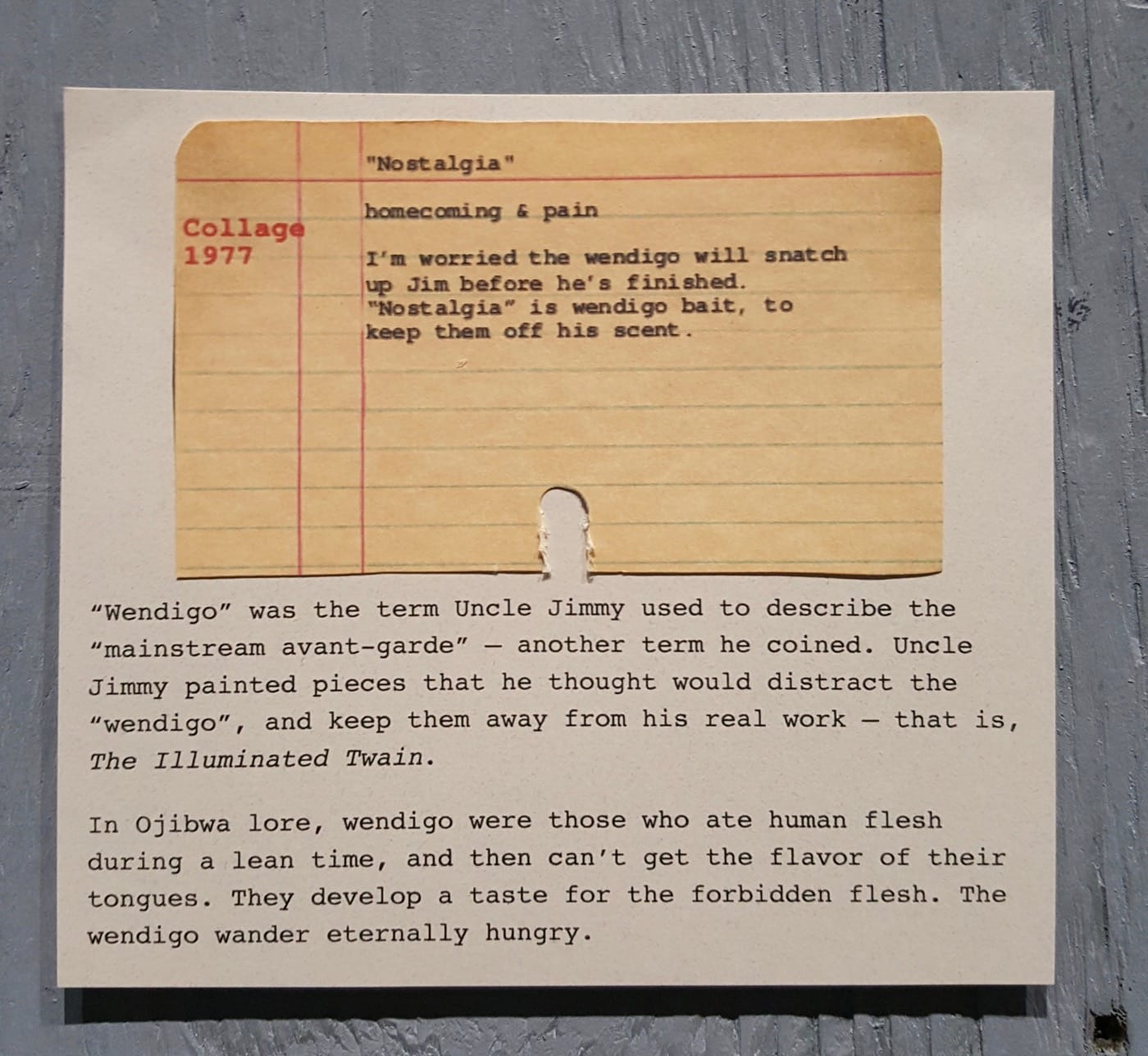

Best of all are the irascible captions written by Uncle Jimmy on ruled, yellowed note cards, like the one for the collage “Magical Negroes,” dated 1980: “found images (Ebony, Jet magazine, Polaroids of antebellum figurines); A gallon of Huck’s tears is not worth a single drop of Jim’s blood.” The piece is what he describes: a collage of magazine covers and mass media images of prominent black celebrities, from Michael Jackson to Haile Selassie, that reveal the artist’s pride in people who are seemingly at the center of culture. There are other brilliant captions, for example, the one for “Illumination #29: Paige Turner,” dated 1996: “Good terrorism destroys a culture’s deepest held beliefs — like how in the 19th century, the anarchists once tried to destroy the clock in Greenwich, England to rattle the British Empire’s assumption that it was the center of time itself.” Uncle Jimmy emerges here as a black artist who’s both profoundly aware and deeply critical of the historical legacy he’s inherited. You can see his character in the gallery: sharp, with sharp edges.

A performance follows, a memorial service conducted by the surviving members of the artist’s family — his (white) wife, Edna Finn, and his estranged son, James “Soulbutter” Clemens — that fills in more of his story. Unfortunately, the exposition of Uncle Jimmy’s life through their accounts is predictable. As Finn, Anne O’Sullivan tells us that he didn’t dislike white people, per se, he just wasn’t interested in them, and that much of his archive has been lost, so we’re only seeing fragments of his oeuvre. She brings out more of his exceptional story, but her weeping feels pro forma and thus breaks the spell. Mikeah Jennings, playing Soulbutter, is even more clichéd in his cadences, though he has great anecdotes as the son his father never fully accepted but nevertheless treated as a co-conspirator: James junior was made to walk barefoot across a field where a massacre was supposed to have taken place, in order to find out whether genocide can be sensual. His stories are intriguing, but Jennings pauses for effect too much, as if he’d been cast for the first season of Roots.

It’s smart for the playwright to work off of Twain’s novel. The framing gives Uncle Jimmy added dimension, by revealing how he’s driven to enter into dialogue with other artists to address history, and the journeys of the novel’s characters Jim and Huck place the artist’s experiences in clear relief. As the memorial service program states of Uncle Jimmy’s sense of his own endeavors (which he maps onto a trip down the Mississippi River): “A ‘Fool’s Eddy’ is where you think you’re moving the culture forward, but you’re just stuck going around around in circles.” In Twain’s novel, though Jim is actually a free man, he’s not recognized as such and suffers the consequences; Uncle Jimmy never quite achieves the art world recognition that may have freed him from his anxiety about his social status as a black man and the wealth he doesn’t own. In one piece in the gallery, you can listen to a recording of the elder James talking to his son about various things, ultimately working up to asking to borrow money.

Master made me think of Sandow Birk’s 2000 exhibition The Great War of the Californias, which explicated a fictional war through the fashioning of supposedly documentary paintings, artifacts, newspaper accounts, weapons, and models of battle ships. The war emerges through the gathering of these sundry elements. In Master, a similar tactic is used to bring a fictional artist into existence, someone we’re fascinated by precisely because he’s so irascible and misanthropic, yet visionary. It’s a familiar depiction, but Master helps us understand that we likely crave the story more than the person behind it.

The play reveals this odd, disconcerting paradox: we mythologize artists, but do so with precisely the attributes of authenticity we ironically think make them more real. It’s as if we want genuineness but don’t quite know how to grasp it. Master brings up the question of where artists actually exist in their careers — we think we see them, when they are not really there at all.

The Foundry Theatre’s Master continues at Irondale Theatre Center (85 South Oxford Street, Fort Greene, Brooklyn) through June 24.