Wifredo Lam No Longer Waits by the Coatroom

An overdue MoMA show reminds us that Lam pursued his own dialogue with African and Afro-diasporic visual cultures, even as the Parisian avant-garde exoticized his heritage.

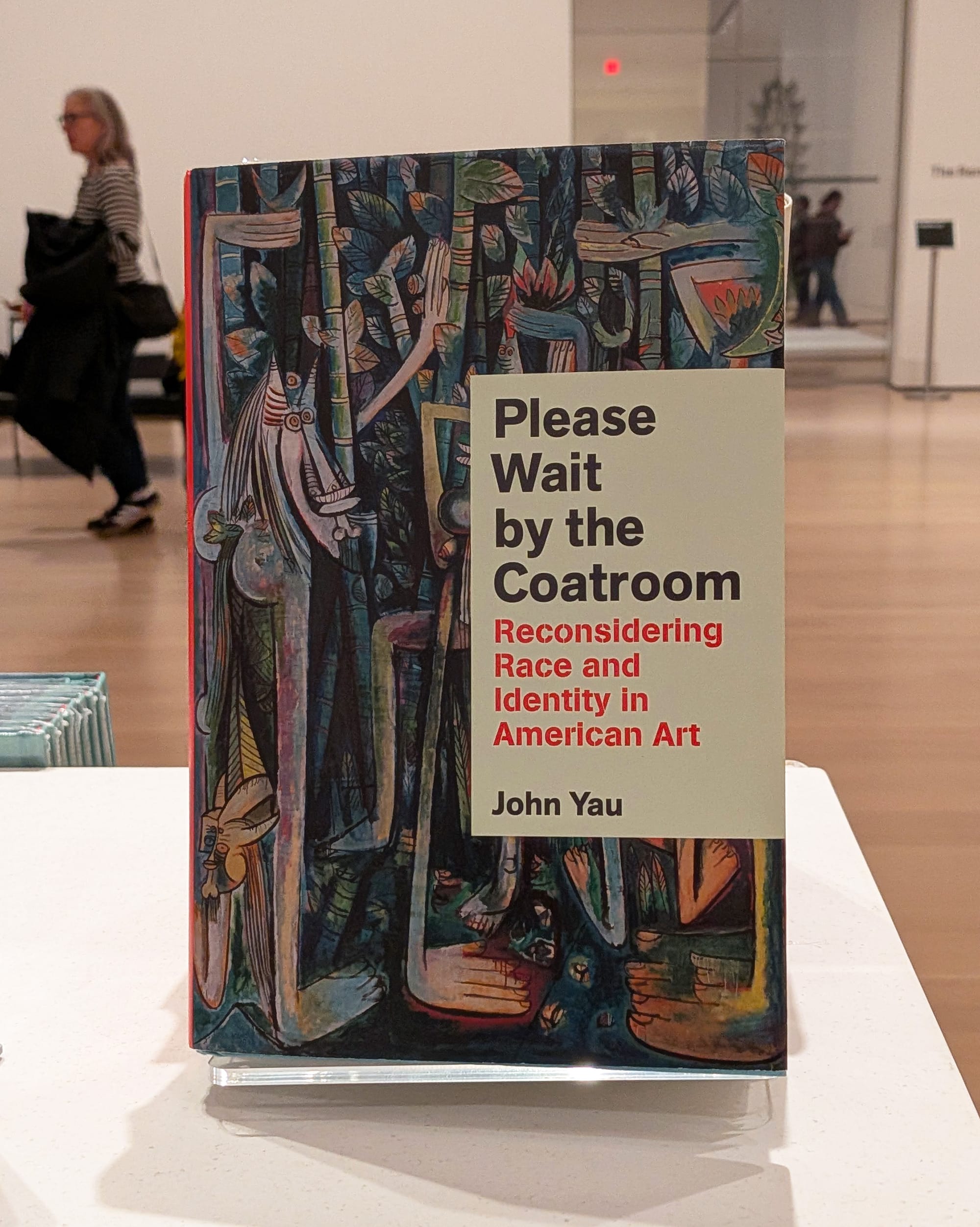

An artwork’s position in the museum, both spatially and interpretively, matters. It was this architecture of visibility that fueled critic John Yau’s landmark essay “Please wait by the coatroom” (1988), titled after the corridor where the Museum of Modern Art (MoMA) once relegated Cuban artist Wifredo Lam’s painting “La Jungla (The Jungle)” (1943). For years, the painting hung in the lobby beside the bag-check — technically public, yet outside the main galleries and the art history they conveyed. Yau read that placement as emblematic of Lam’s broader marginalization and of MoMA’s reluctance, at the time, to accommodate his cultural and political commitments in the formalist narrative of modernism it was building.

Nearly 40 years later, the museum has mounted a retrospective that finally gives Lam’s work the space to occupy the full measure of his practice. When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream charts his trajectory from early training in Spain to transformative years in Paris, a decisive homecoming during World War II, and the radicalizing decades that followed.

Born to an Afro-Cuban mother and Chinese father in 1902, Lam studied art in Spain before the outbreak of the Civil War — in which he served briefly — and relocated to Paris in 1938, where he befriended leading artists and writers, including Pablo Picasso, André Breton, and Óscar Domínguez. In these years, Lam’s work moved decisively toward a modernist vocabulary. He absorbed Cubist structures, experimented with fractured geometries, and became increasingly drawn to Surrealism’s investigations of automatism and the subconscious. The exhibition displays some of his contributions to exquisite corpses and illustrated collective poems with Breton, Jacqueline Lamba, and others. Producing uncanny composite bodies and unexpected metamorphoses, these exercises shaped Lam’s own developing imagery and deepened his belief in the emancipatory possibilities of the unconscious.

Lam entered the Surrealist orbit at a moment when the avant-garde’s fascination with the “primitive” (shorthand for the Americas, Africa, Oceania, and other non-Western cultures imagined as raw, authentic, and outside history) too often blurred into fetishization. Its core impulse — treating non-Western objects as catalysts for Western creativity rather than as culturally situated forms — is a dynamic whose premises were later echoed in MoMA’s widely criticized 1984 “Primitivism” exhibition. As scholars like Michele Greet and Lowery Stokes Sims have shown, Lam’s early career was shaped by a complex positionality within these circles: He pursued his own dialogue with African and Afro-diasporic visual cultures even as the Parisian avant-garde exoticized his heritage.

That tension — being racialized while renegotiating the frame imposed on him — remains central to understanding his work. MoMA’s exhibition leaves this context mostly unexplored; instead, much of this complexity is taken up by the excellent catalog. There, a 1946 photograph of Lam’s second wife, Helena Holzer, amid his paintings and their personal collection of African and Oceanic objects could pass for a Surrealist salon. But his engagement with these objects was hardly naïve. Years later, he would describe feeling like those very sculptures — “an exotic [...] transplanted here,” rendered “sterile” once torn from the communities that created them, as quoted in the catalog. Throughout his career, Lam grappled with what it meant to inhabit a cosmopolitan, diasporic identity while guarding his work against the essentializing ideas placed upon it — a point he made with stark clarity when he wrote in that same letter, “Yesterday they sold black flesh, today they monopolize the black spirit.”

After fleeing German-occupied Europe in 1941 for Martinique, Lam met the poet and politician Aimé Césaire. Their exchange — later deepened by Lam’s illustrations for Césaire’s Cuban edition of Return to My Native Land (1943) — introduced him to the Négritude movement’s anticolonial vision of Black consciousness and belief in the marvelous as a tool for imagining liberation. When Lam returned to Cuba in 1942, after 18 years away, that encounter sharpened his resolve to confront the island’s racial hierarchy and political repression.

The creation of “La Jungla,” the centerpiece of When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream, is widely regarded as the moment when Lam reclaimed African-derived forms that European modernists had aestheticized into abstraction, returning them to political charge. The painting depicts an Antillean thicket where limbs unfurl into sugarcane, the commodity that anchored centuries of Caribbean resource extraction and enslavement. Lam likened it to a Trojan horse meant to “spew forth hallucinating figures” capable of unsettling colonial fantasies — a description that anticipates the hybrid, syncretic spiritual vocabulary of his later paintings, and clarifies how strategically he deployed a seemingly familiar modernist syntax.

The retrospective shines in underscoring how inseparable Lam’s work was from questions of Black identity and what he himself called “mental decolonization.” Lam wasn’t merely adapting European modernism; he was rerouting it. The exhibition’s later rooms chart how Lam developed a pictorial language rooted in Afro-Caribbean religions — Lucumí, Vodou, and other traditions — distilling their symbols into horned heads, knife-blades, bird forms, horseshoe arcs, and mask-like hybrids. This imagery animates works like “Bélial, empereur des mouches (Belial, Emperor of the Flies)” (1948) and the Femme-Cheval paintings, where human, animal, and vegetal forms merge. His monumental drawing “Grande Composition” (1949) — once used as the backdrop for the first public reading of a play by Césaire about the Haitian Revolution — carries that language into a broad, processional panorama. Nearby, Lam’s lesser-known ceramics translate the same hybrid syntax into three-dimensional jagged forms.

Lam has long occupied an ambiguous place in MoMA’s narrative of modernism — present from the beginning but rarely granted the interpretive frame his work requires. “Mother and Child” (1939), shown in Lam’s first solo exhibition at Galerie Pierre in Paris, was acquired by MoMA’s first director Alfred H. Barr Jr. and became the first of his paintings to enter any museum collection worldwide. That early endorsement is meaningful. Still, collecting only establishes presence, not position. Long before Yau sharpened that point, MoMA kept “La Jungla” in what curators Beverly Adams and Christophe Cherix call a “prominent limbo” in this exhibition catalog: visible enough to signal inclusion, yet structurally outside the museum’s account of modernism.

When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream, Lam’s first US retrospective, arrives at a fundamentally different MoMA: one that now insists on a global account of modernism after decades of advocacy both in and outside its walls, has built a dedicated infrastructure around Latin American art, and has normalized exhibition cycles that once would have been exceptional. The show reads as a corrective — an institutional acknowledgement that Lam’s work cannot be understood outside the contexts of diaspora, colonial history, and cultural negotiation that the museum itself once avoided. It’s the kind of rare artist-institution encounter that becomes a measure of the museum’s own evolving commitments. And as if to remind us that museums narrate themselves through more than just wall texts, an edition of Yau’s essay, which once called out MoMA from the sidelines, now sits unassumingly in the gift shop.

Wifredo Lam: When I Don’t Sleep, I Dream continues at the Museum of Modern Art (11 West 53rd Street, Midtown, Manhattan) through April 11, 2026. The exhibition was curated by MoMA Director Christophe Cherix and Curator of Latin American Art Beverly Adams, with Curatorial Associate Damasia Lacroze and Curatorial Assistant Eva Caston.