Painting a Kangaroo When You've Never Seen One

To show animals of distant locales to the public in centuries before photography, artists were sometimes enlisted to recreate exotic fauna through secondhand descriptions or some scrap of skin or skeleton.

To show animals of distant locales to the public in centuries before photography, artists were sometimes enlisted to recreate exotic fauna through secondhand descriptions or some scrap of skin or skeleton. Strange Creatures: The Art of Unknown Animals, opened in March at the Grant Museum of Zoology at University College London, examines this often inaccurate first glimpse of an unknown animal.

The centerpiece is George Stubbs’s “The Kongouro from New Holland (Kangaroo)” (1772), considered the oldest European painting of a native Australian animal. The 18th-century marsupial and its companion painting of a dingo (not included in Strange Creatures) almost left the UK, but in 2013 were stopped in an export ban and purchased through a donation by the National Maritime Museum. Slightly misshapen, as it was based on a puffed up skin and skull acquired by Captain Cook, the kangaroo with its dark canny eyes is now on a British tour. After the Grant Museum, the painting visits London’s Horniman Museum and Gardens, the Captain Cook Memorial Museum in North Yorkshire, and then the Hunterian Museum in Glasgow.

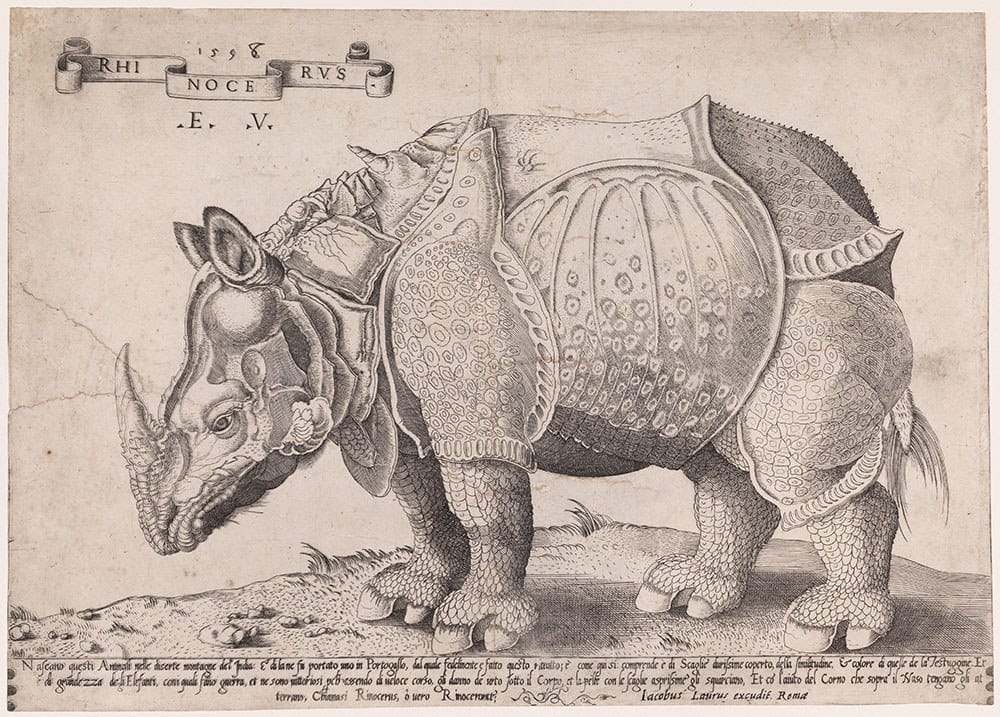

Strange Creatures is installed amidst the Grant Museum’s zoological specimens: a herd of intact and partial belated animals hovering in jars. This is a purposeful contrast between the biological specimens and those artistic interpretations. The most famously wrong and wildly popular Dürer’s rhinoceros is shown copied in 1558 by Enea Vico, a mammalian version of a tank, sporting skin that weighs like armor with an extra horn on its shoulders. Neither artist had ever seen the animal in person.

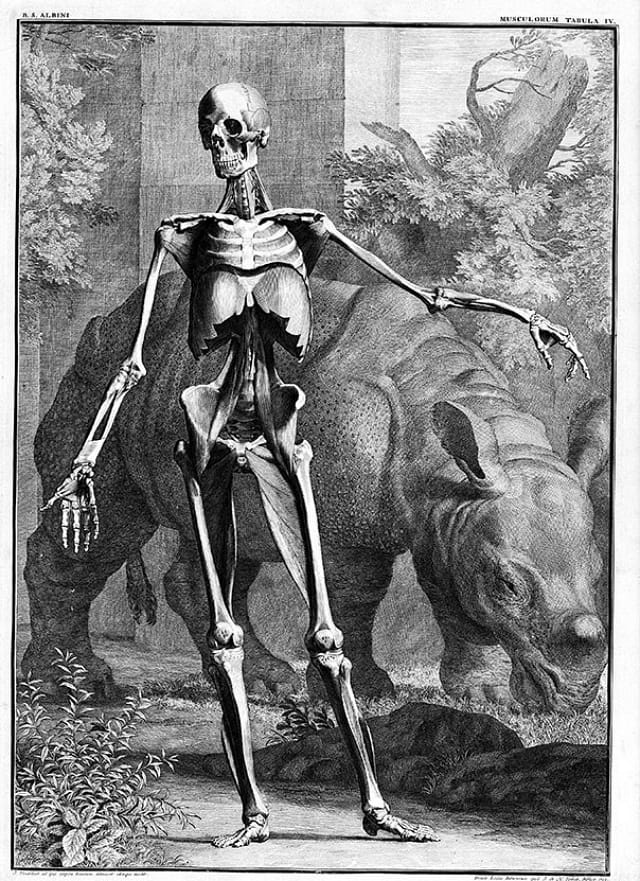

The Dürer-inspired rhino is contrasted against a much gentler beast in the background of a 1747 anatomical illustration by Bernhard Siegfried Albinus, the rumple-skinned animal grazing while a flayed skeleton poses in the foreground. This later depiction was based on the rhinoceros Clara, who toured Europe for 17 years in the 18th century, and was the first rhinoceros to appear on the continent since 1579.

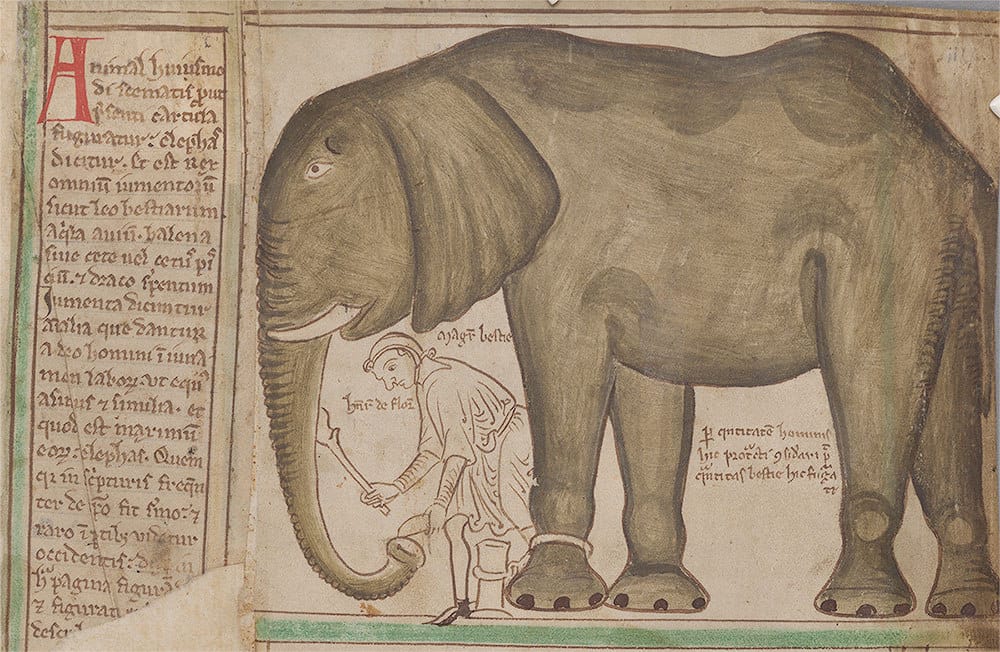

Similarly, the first elephant illustrated by Matthew Paris for the 13th-century Chronica Maiora shows a comically long beast with a pudgy belly drawn in 1241, while in the same work a much more accurate elephant from 1255 was modeled on a real-life animal that was at the Tower of London.

In later centuries, models and dioramas turned the skins of animals into more dimensional interpretations, although they still often got it wrong, like the overstuffed 1860s Horniman Museum walrus with not a wrinkle on its inflated body. The Grant Museum emphasizes that despite our greater capacity for communication, inaccuracies continue, such as with toy dinosaurs that perpetuate the 19th-century view of lizard-like dinosaurs with dragging tails, something now disproved.

And going back to the Stubbs kangaroo, the anatomically-imperfect animal is still has a presence, from appearing on Australia’s first coat of arms to inspiring numerous engravings. Now we can Google all the kangaroo photographs we like (an activity that’s recommended), but it’s still worth looking back at these first impressions and considering their shadow, based more on artistic interpretation than live science.

Strange Creatures: The Art of Unknown Animals continues at the Grant Museum of Zoology at University College London (21 University Street, London) through June 27.