The Idealism of Early Soviet Russia in Pictures

The Jewish Museum’s The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film examines the beginnings of Soviet Russia, positing that the period from 1921 to 1932 was one of avant-garde artistic experimentation, a time when photographers and filmmakers (many of them Jewish) imagined their c

The Jewish Museum’s The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film examines the beginnings of Soviet Russia, positing that the period from 1921 to 1932 was one of avant-garde artistic experimentation, a time when photographers and filmmakers (many of them Jewish) imagined their craft to be as radical as the social changes it reflected. The exhibition is a good introduction to big themes in early Soviet photography and film, but it fails to probe the relationship between the period’s revolutionary artistic styles and political themes that troublingly foreshadowed Stalin’s totalitarian state.

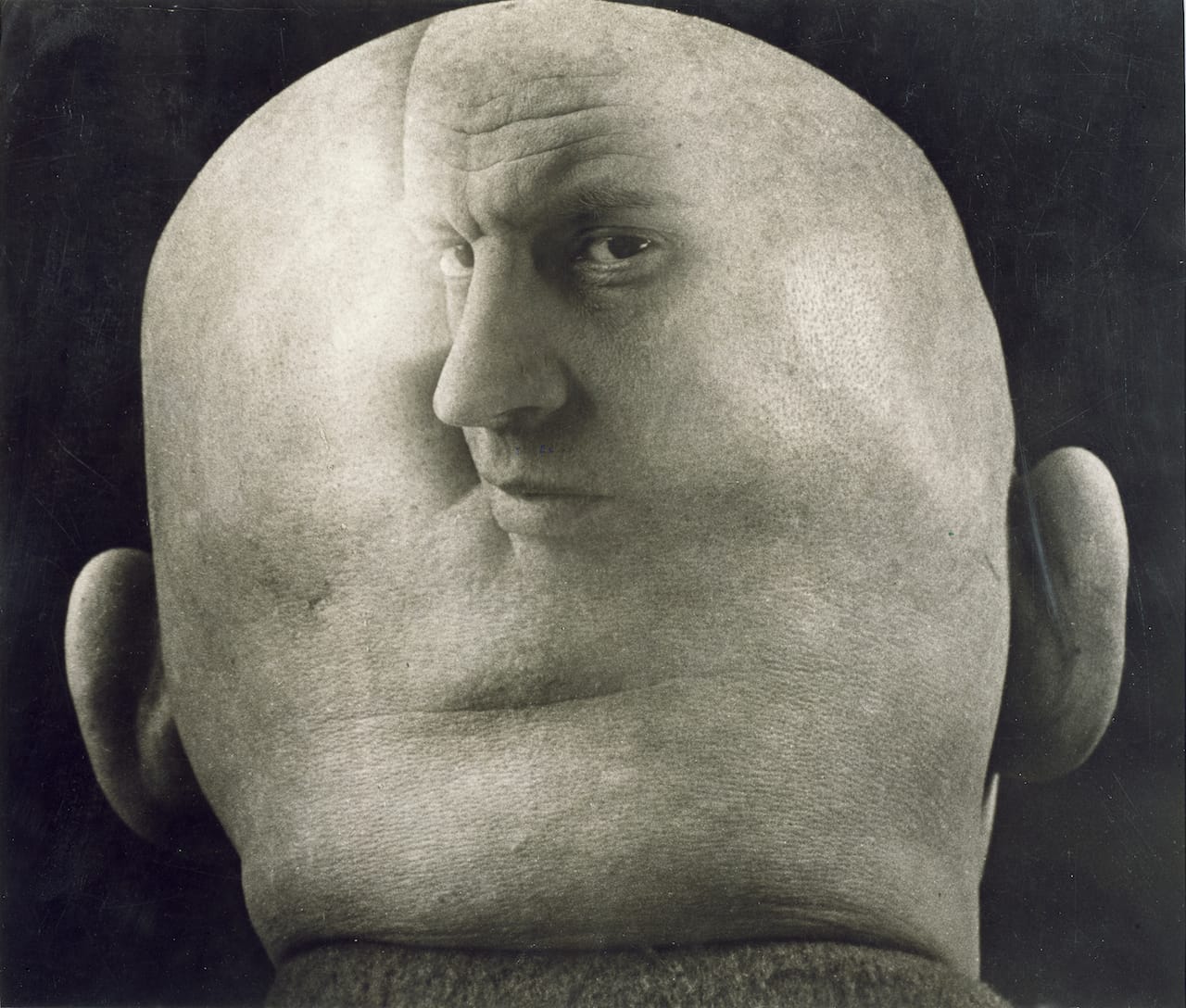

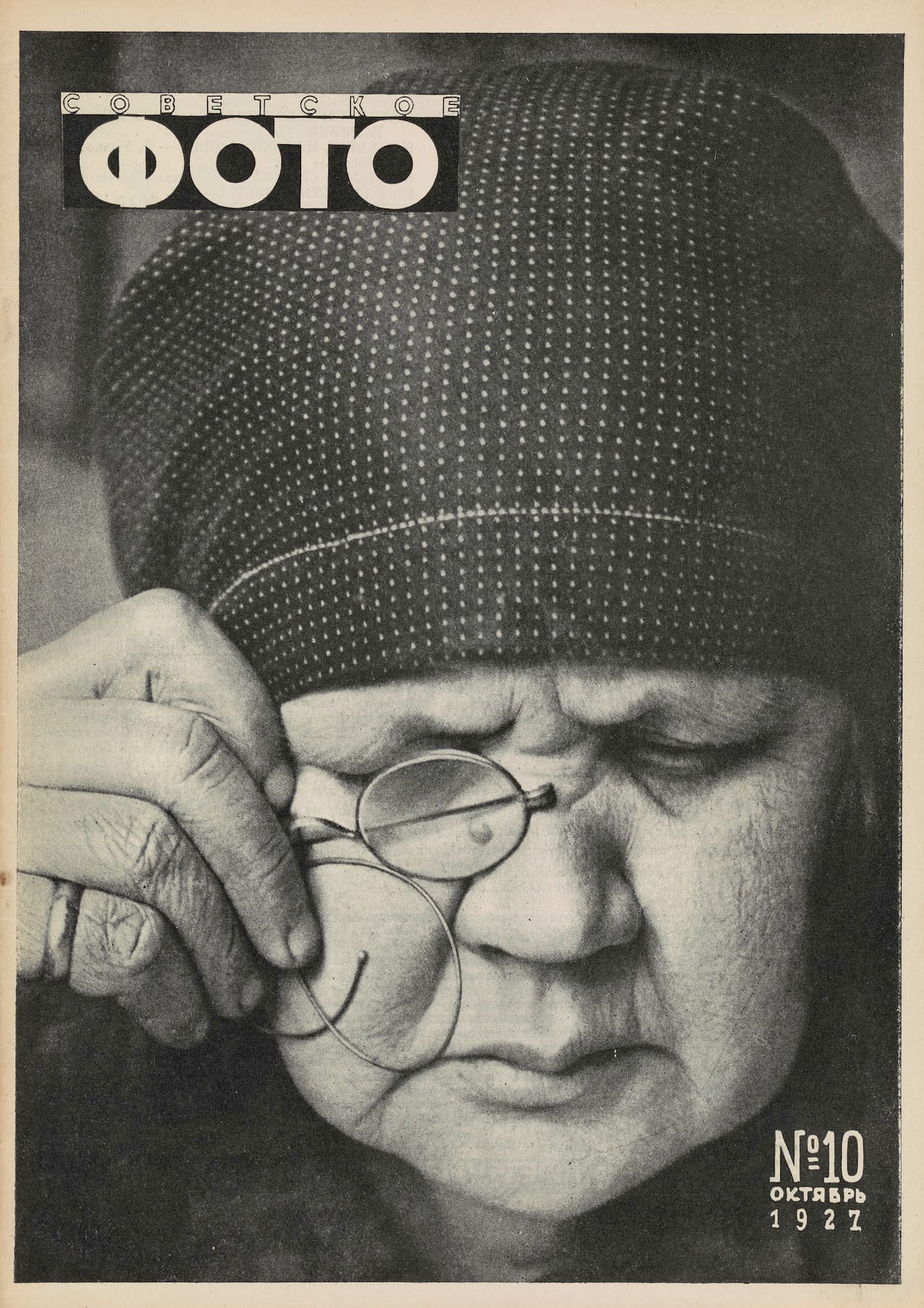

The Power of Pictures is organized thematically, with sections such as “New Perspectives,” “Constructing Socialism,” and “Staging Happiness” delineating how photography both mirrored and constructed social change. (A section of film posters and a screening program offer an accompanying overview of the cinema of the time.) The exhibition begins with work that’s technologically and formally innovative. In Georgy Petrusov’s “Caricature of Alexander Rodchenko” (1933–34), Rodchenko’s face, seen from a side angle, is superimposed onto an image of the back of his head. The result is moody, evoking sci-fi visions of genetic engineering. Petrusov sacrifices a veritable likeness for an abstracted image suggesting a more psychological identity. A cityscape by Rodchenko himself, “Stairs” (1929–30), shows a woman carrying a small child up a flight of public stairs. We see the woman from behind, and neither her nor the child’s expression is clearly visible, their figures subsumed by the repetitive geometry of the steps. Images like this, of individual identities subjugated by technology and the urban landscape, subtly evoke the potential of a totalitarian state, even if the photographers were unaware of it.

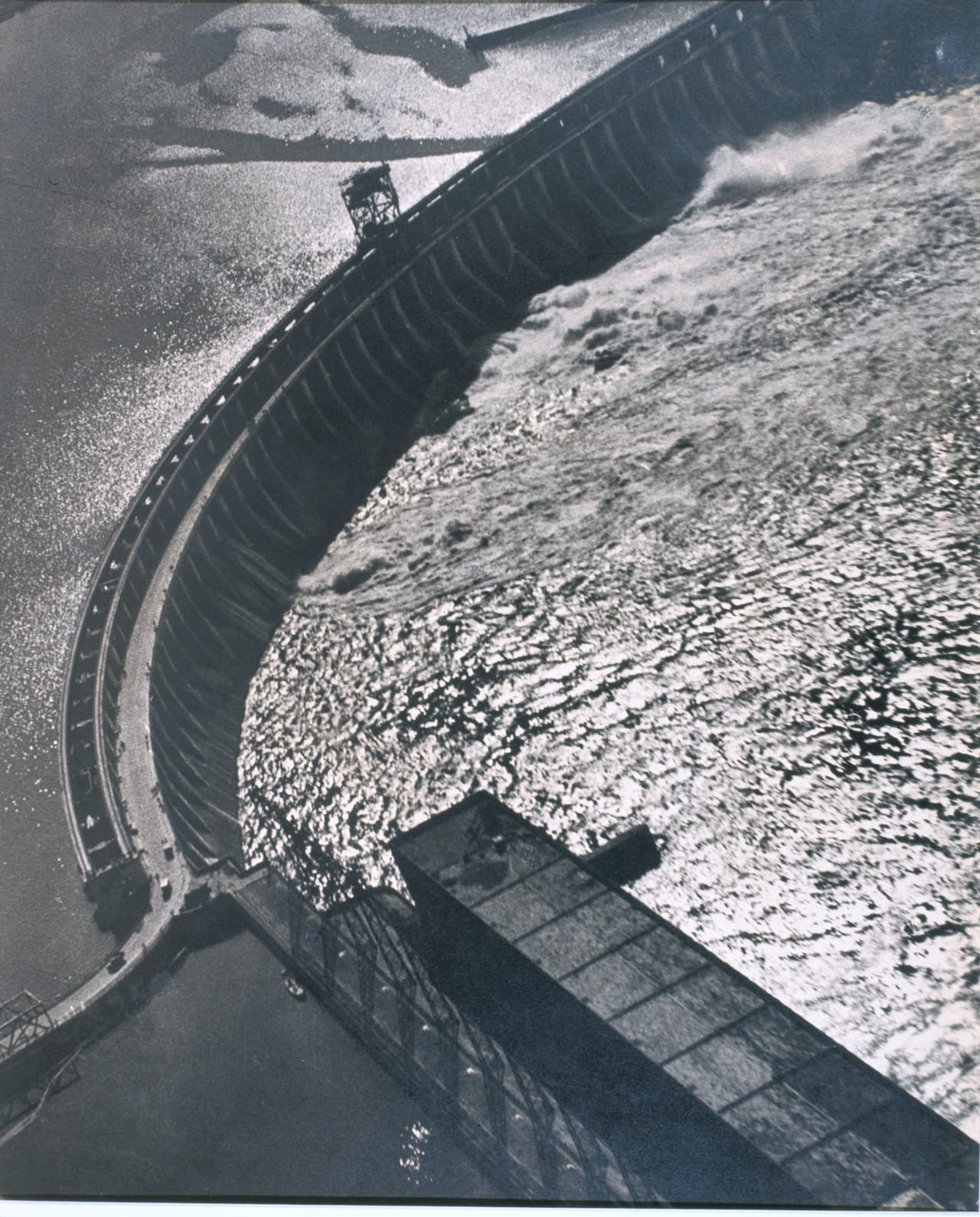

The “Metropolis” and “Constructing Socialism” sections capture the perception of industry and technology as primary engines of a new society. Arkady Shaikhet’s photograph “Assembling the Globe at Moscow Telegraph Central Station” (1928) presents the outlines of two male figures, slightly distorted by the curvature of a human-sized globe they are constructing from the inside — the worker literally building the world. Georgy Petrusov’s “Dnepr Hydroelectric Dam” (1934–35) appears tilted within the frame to mimic the curvature of the Earth — industrial production as perfectly harmonious with the natural world.

The final photography sections of the exhibition — “Constructing Socialism,” “Military,” “Soviets,” and “Staging Happiness” — chronicle the increased tightening of artistic expression to conform to Soviet ideology. Themes that are only suggested in earlier sections here become obvious. These works are endowed with a particular glamour meant to manipulate viewers into accepting an idealized, politically whitewashed version of everyday Soviet life. Arkady Shaikhet’s “The Parachutist Katya Melnikova” (1934), for example, shows a young woman emerging from an airplane. The lines of her upper body are highlighted against the sky; she appears as the epitome of both glamour and physical fitness. In Rodchenko’s “Sports Parade on Red Square” (1936), a line of young, smiling, barelegged women steps in Rockette-level synchronization.

The Power of Pictures suggests that totalitarianism appeared from the outside, offering a narrative that starkly delineates early Soviet idealism from Stalin’s evil. The exhibition fails to acknowledge that this idealism — in which individualism is subsumed under a greater political purpose — contains the potential for repressive application. As the introductory wall text states, “A large number of the most prominent photographers, photojournalists, and filmmakers were Jewish; as members of a recently emancipated minority, they welcomed the arrival of the Soviet Union, with its promise of a new, egalitarian world.” There is an innocence to the early work on display, an unawareness of how seemingly egalitarian ideals could be applied to authoritarian ends. The Power of Pictures would have done well to explore this progression for a more nuanced snapshot of the period.

The Power of Pictures: Early Soviet Photography, Early Soviet Film continues at the Jewish Museum (1109 Fifth Avenue, Upper East Side, Manhattan) through February 7, 2016.