Revisiting the Anti-Establishment Posturing of an Established Artist

Tucked into the corner of Marlborough Chelsea’s huge space sits Viewing Room, an exhibition of Stephen Kaltenbach’s work that expresses, in a variety of media, a very personal sort of art world pique.

Tucked into the corner of Marlborough Chelsea’s huge space sits Viewing Room, an exhibition of Stephen Kaltenbach’s work that expresses, in a variety of media, a very personal sort of art world pique. Though there is no actual sound component to the installation, it is the artist’s voice you first encounter upon entering; a voice with an amusingly acerbic tone.

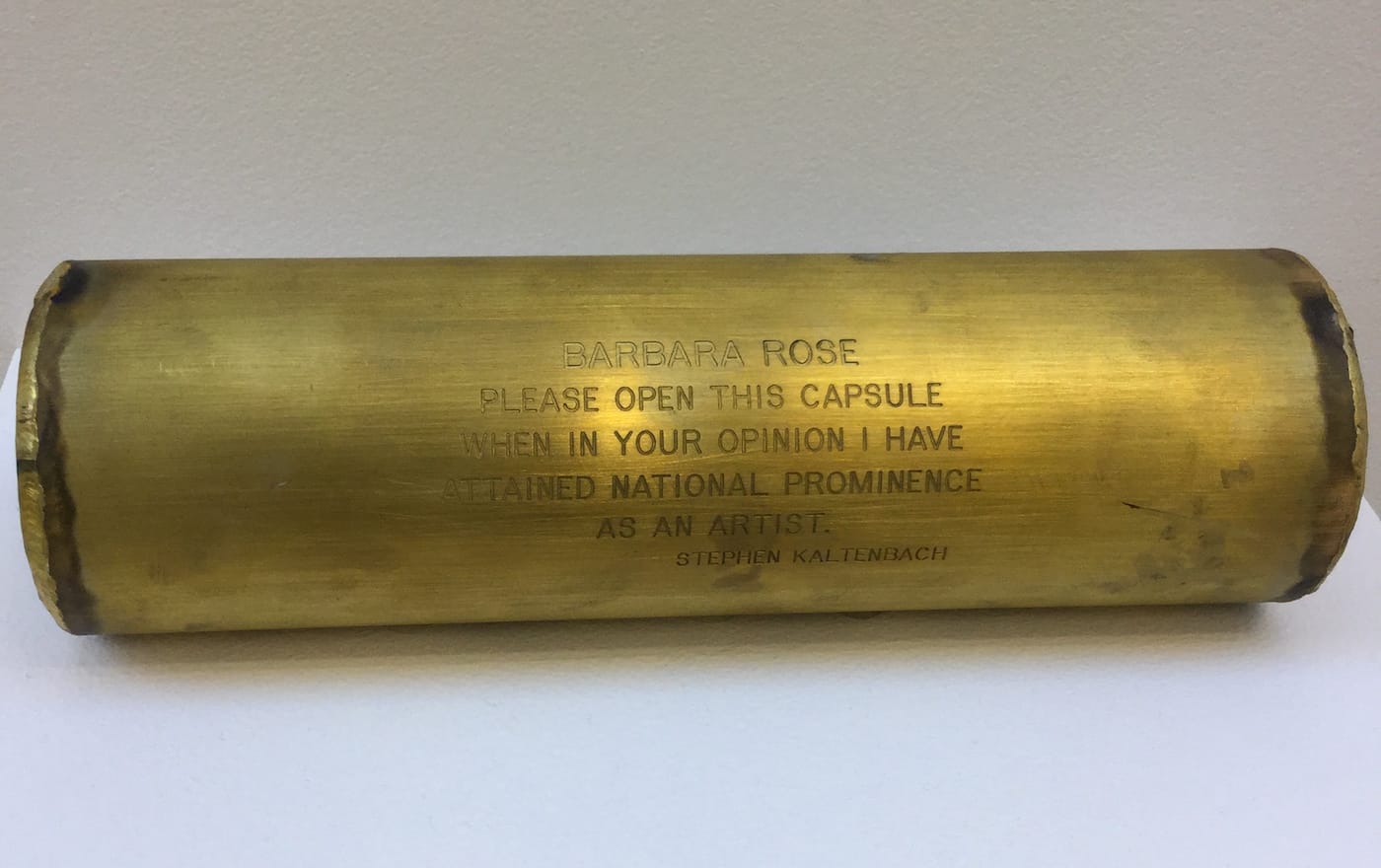

The artist’s grumbling begins with one of several container pieces that resemble time capsules, each with a word or words etched into its surface. In this particular example, “Barbara Rose Time Capsule (Self Appropriation)” (1970), the container is a brass tube three inches in diameter, less than a foot long, resting on a pedestal. The tube has been sealed shut on both ends with a continuous weld. Its contents, or lack thereof, are cryptically addressed by a neatly machine-typed inscription that reads, “Barbara Rose please open this capsule when in your opinion I have attained national prominence as an artist — Stephen Kaltenbach.” Its wry anticipation of a likely rejection evokes a popular joke of unknown origin that tells of a tourist on a busy street engaging a local resident with the words, “Excuse me. May I bother you for the time, or should I just go fuck myself?” The brevity of the one-liner suits the textual attributes of conceptual art, and Kaltenbach makes the most of it, creating a sardonic, mistrustful voice that gives form to an invisible self-portrait, modeled with the aid of a sharp and effective wit.

Strangely though, conceptual artists who rely on humor tend to reject rarefied notions of fine art. Most strive to replace it with a celebration of the ordinary, or in some cases invite the viewer in on a joke. An example would be “Precarious Twister” (2008), by the curator of Kaltenbach’s show, David E. Stone, which faithfully reconstructs the popular game but for the pile of broken glass that substitutes for the familiar plastic sheet. What’s odd about Kaltenbach’s work is how it seems to align with this playful attitude — jokes abound throughout the exhibition — yet its subject matter reflects a myopic preoccupation with his own career.

Stone’s selections for the exhibition focus on this disdain that Kaltenbach seems to harbor for the art world; a disdain that’s not easy to empathize with considering that he has been, for decades, a real (if minor) player in the art world. How, one wonders, will his outsider status hold up to having landed a solo exhibition in a major Chelsea gallery?

His perceived lack of recognition may have made for an appealing shtick in his early development, but as his career sailed along it apparently evolved into a narrative destined to go nowhere. A few biographical notes in the press release corroborate Kaltenbach’s choice to nurture an outsider persona early on. After participating in a string of seminal conceptual art exhibitions — including the 1969 show Live In Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form at Kunsthalle Bern, his solo show Room Alterations at the Whitney Museum in the same year, and the 1970 Information show at the Museum of Modern Art — he left New York and relocated to California, where he has worked ever since. Whether his decision to relocate reflects a perceived relegation to back-bench status in New York, or was the cause of it, is anyone’s guess. What’s undeniable is that Kaltenbach has worked and exhibited for decades. Indeed, Viewing Room is a mini-retrospective; literally so, considering that the space is no more than 200 square feet.

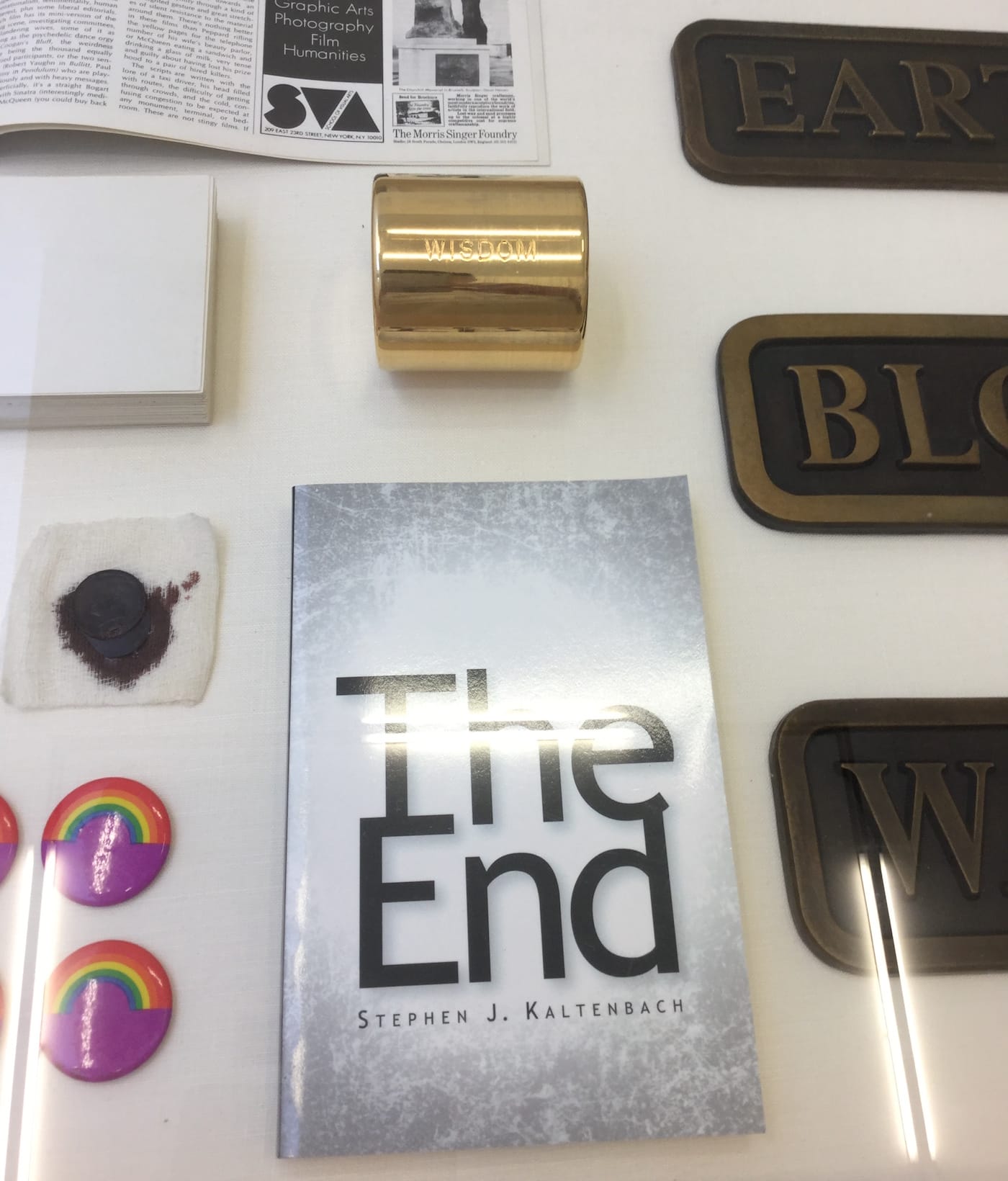

In the center of the room stands a vitrine containing several items, including an example of his early advertisement pieces, a one-eighth-page ad in a late 1960s issue of Artforum that stated “Build a Reputation” in bold type on an otherwise blank rectangle. The joke in this piece, as in many of those reflecting his professional selfhood, lost its edge as his reputation actually grew, albeit modestly. Beside it are license plate-sized bronze castings with a single word — “Earth,” “Air,” “Blood,” etc. — that visitors are told were designed to be embedded permanently in a concrete sidewalk, a sort of low-budget public art. Placed in the center of the display is another rather witty container piece, in this instance a glossy polished brass cylinder etched with the title “Wisdom,” which is more professionally fabricated than the others, yet noticeably smaller.

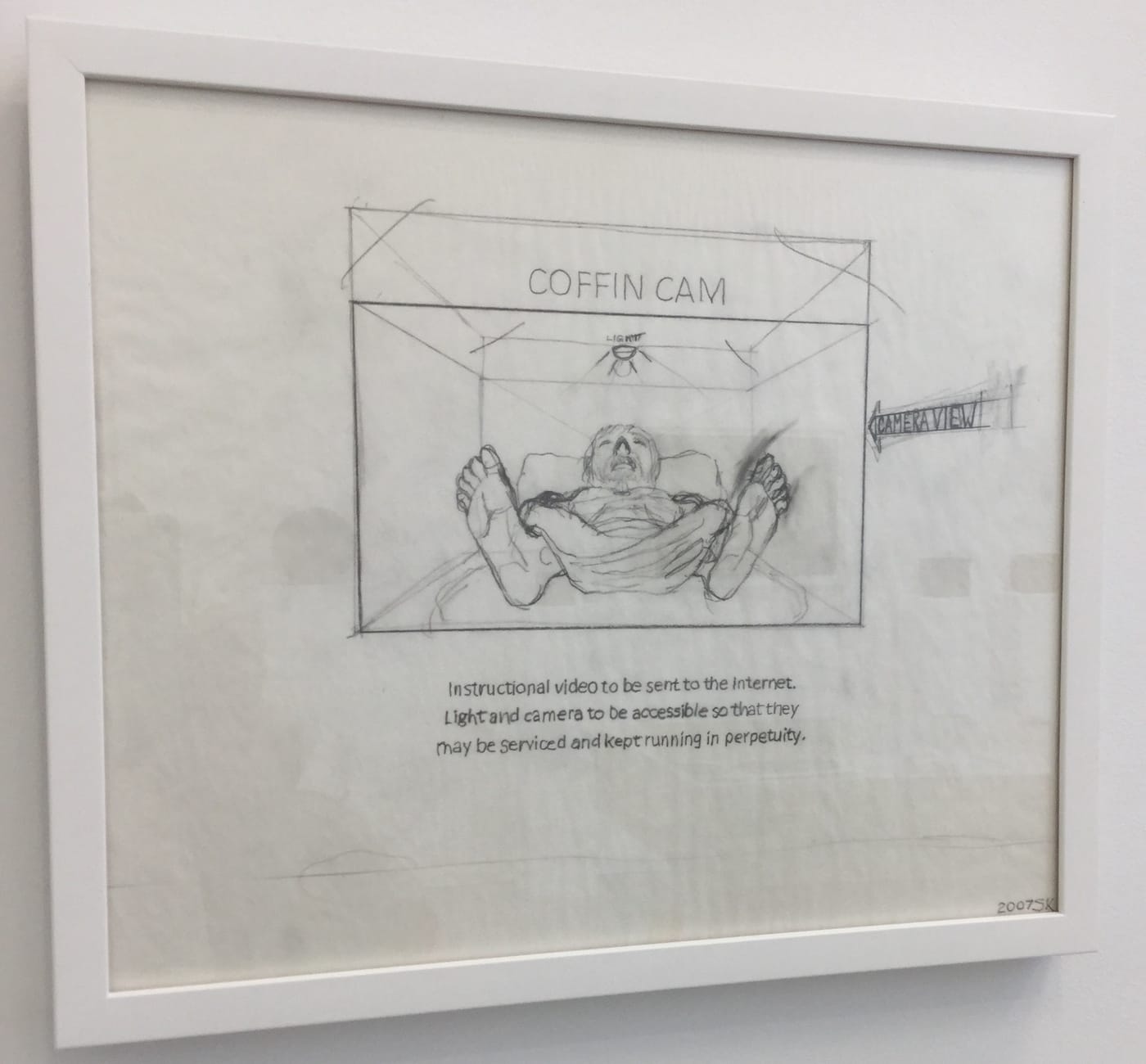

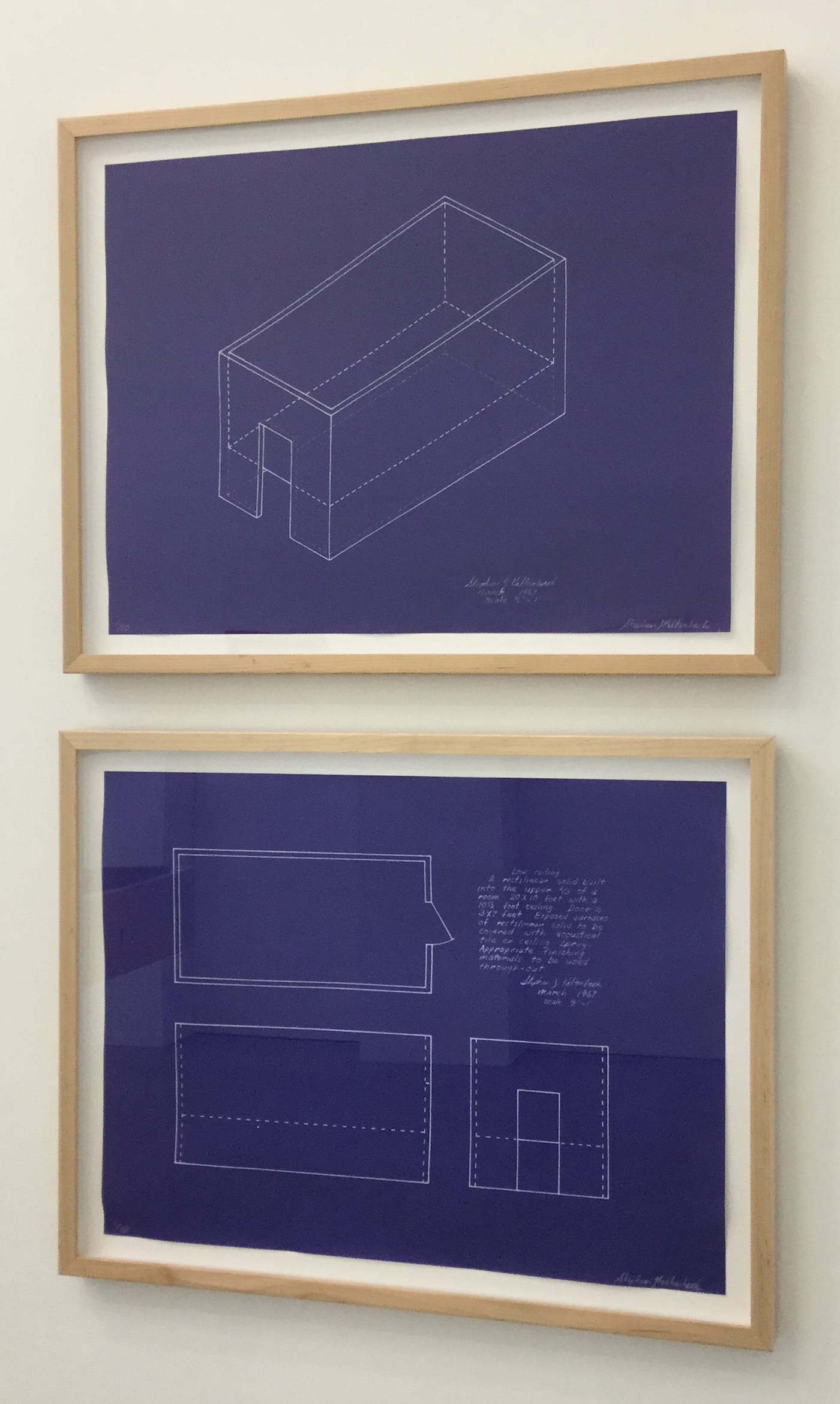

Among the remaining work are “Low Ceiling” (1968–2010), which consists of plans for a room to be filled from ceiling to waist level with an inhibiting structure, and a darkly funny proposal titled “Coffin Cam” (2001) that proposes to install upon his death a permanently functioning video camera inside his coffin that will allow the public to witness his decomposition. As the attitude Kaltenbach had committed to needed to be maintained for credibility’s sake, so the work inevitably becomes a bit overwrought.

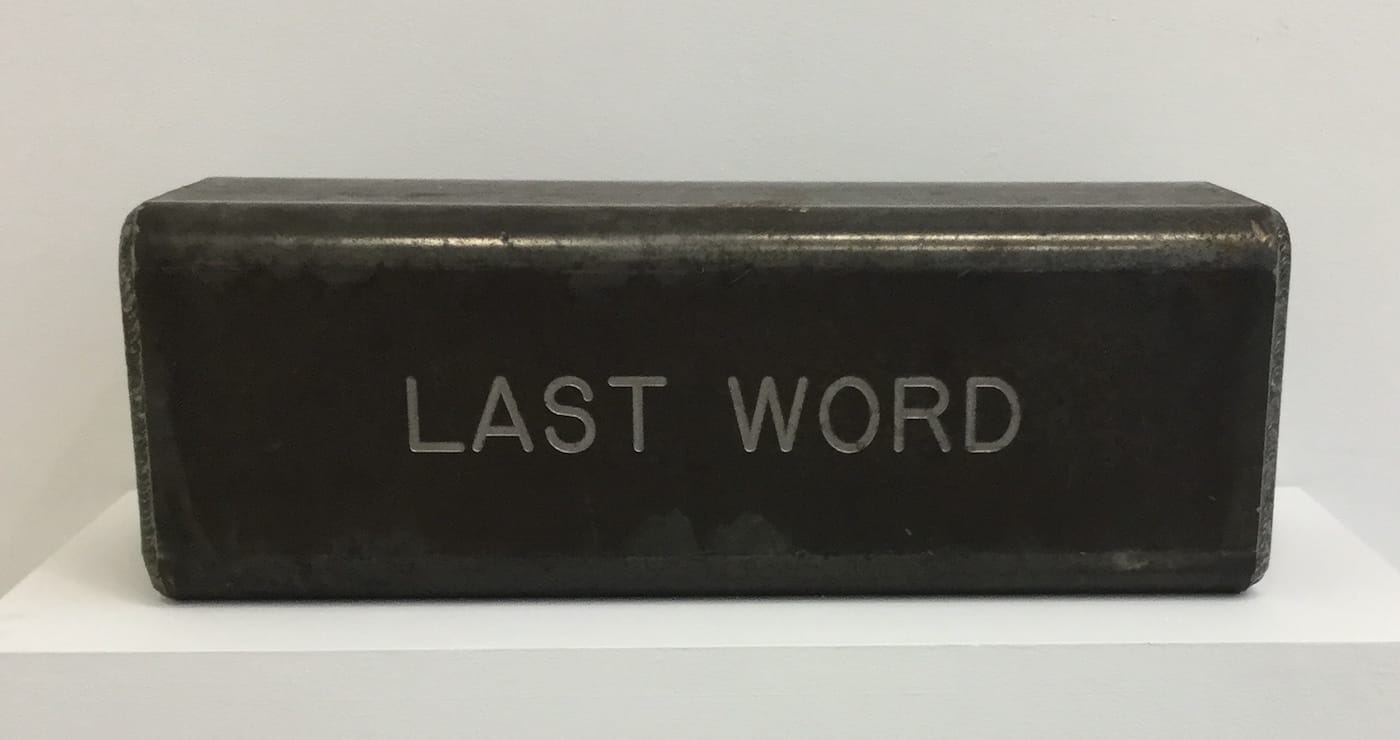

In fact the most interesting pieces in the show are the very ones whose meanings have deflated as the years passed. A trio of nearly identical steel capsule pieces — “Last Act,” “Last Word,” and “Last Thought” — that were all made in 1970, which was very early in his career, seem in their present retrospective context more like youthful posturing than the world-weary resignation they imply. Finished with a sort of gunmetal patina and each inscribed with its title, their visual heft cries out for recognition as a three-part epitaph, though by the logic of their premature sealing (and despite each label’s claim of “unknown contents”) they are to a current viewer obviously empty. The joke is in their having lasted into the artist’s seventh decade. They are now symbols of Kaltenbach’s youthful cynicism — poignant in their message, but perhaps not as he originally intended.

Viewing Room: Stephen Kaltenbach continues at Marlborough Chelsea (545 West 25th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) through June 18.