Why a Diego Rivera Still Life Hangs in Steven Spielberg's The Post

The Cubist painting "No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole" fits surprisingly well with themes in the Oscar-nominated film.

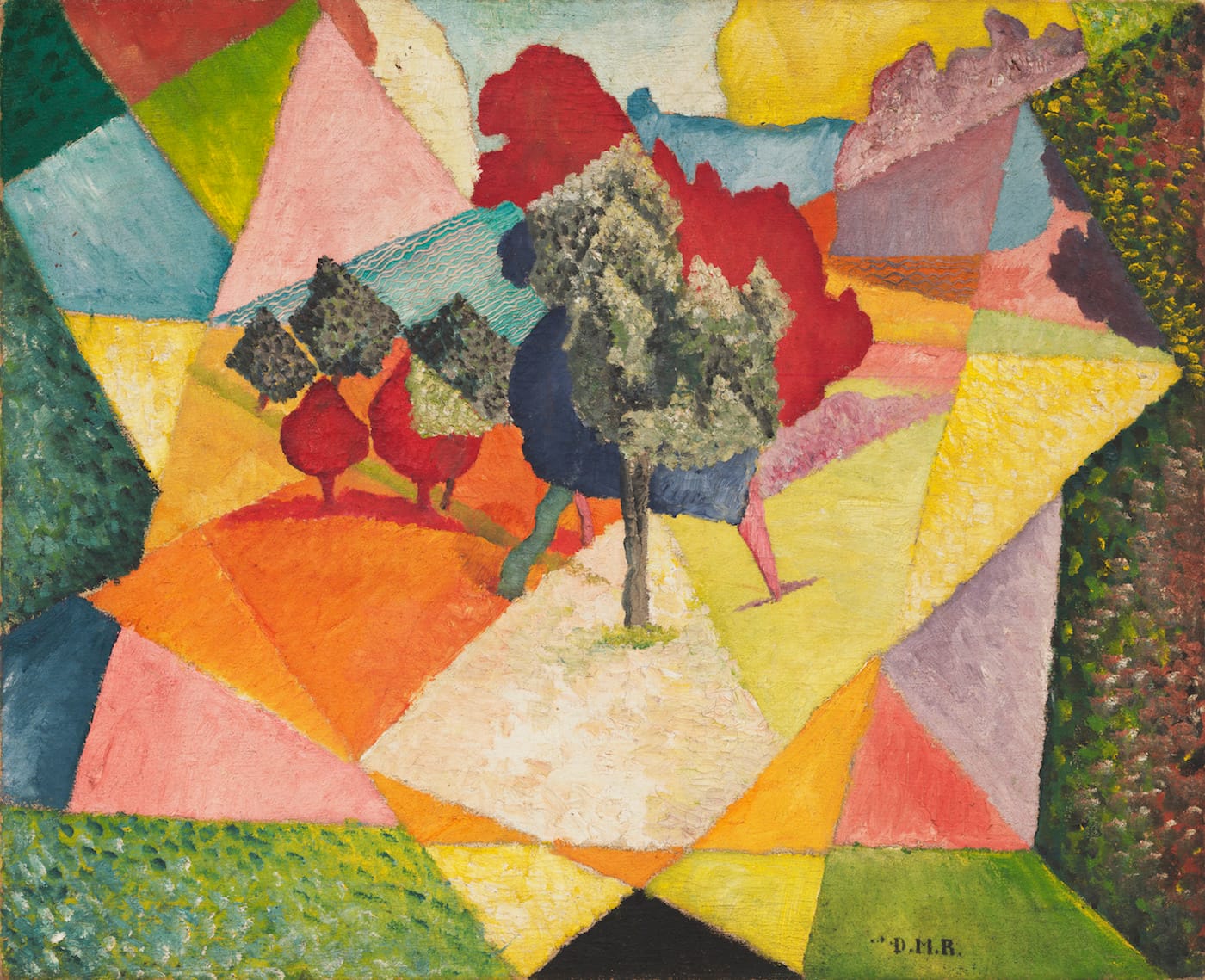

As Meryl Streep delivers her first lines in The Post, the Oscar-nominated film from Steven Spielberg, the camera pans over a distinctive Cubist still life, in which fragmented planes of purple and yellow serve as a backdrop for a clay pot with a teal shadow. It hangs on a set inspired by the Georgetown home of Katharine Graham, former publisher of the Washington Post. The painting is “No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole” (1915) by Diego Rivera.

Set decorator Rena DeAngelo included the painting in an attempt to highlight Graham’s impressive art collection. Yet by cinematically transporting the Rivera painting from its real-life location in Graham’s library to the Hollywood version of her study, the film grants the still life a supporting role, of sorts, in the background of several dramatically critical scenes. The painting turns out to be a surprisingly good fit for the movie and its themes.

“Quality and profitability do go hand in hand,” the fictionalized Graham declares in her opening scene, as she rehearses for a meeting about the newspaper’s plan to go public as a company. She glances left, toward the fireplace mantel, above which the painting hangs. Later, the painting reappears when Washington Post editor Ben Bradlee, played by Tom Hanks, warns Graham that he will soon obtain copies of the classified Pentagon Papers. And it appears yet again in the pivotal moment when Graham must decide whether or not to publish the papers, risking the financial collapse of her newspaper, even personal imprisonment.

But how did this Cubist still life end up in Graham’s Georgetown home, and what might it say about Graham and The Post? Its journey to Washington, DC began when she was still in utero and her mother, Agnes Ernst Meyer, went to Rivera’s first US exhibition at the New York gallery of Alfred Stieglitz.

Meyer first met Stieglitz around 1907, when she was a journalist at the New York Morning Sun. She was looking, in her words, “to discover curious people who would make good copy.” Later, as a married woman, Meyer lent financial support that allowed Stieglitz to open his Modern Gallery. In her autobiography, Meyer reminisced that she “took a lively part during the first years of marriage in the struggle to interest New Yorkers in modern French art which Alfred Stieglitz was carrying on in his little hole in the wall.”

That hole in the wall helped introduce Diego Rivera to American audiences. His first US exhibition took place there, in 1916. And it was there that Meyer purchased “No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole,” while pregnant with Katharine Graham. (She also bought the 1912 painting “Cubist Landscape,” now at the Museum of Modern Art, and the 1911 painting “Montserrat,” now at the National Gallery of Art.)

Meyer’s selections would have been considered brazen, by many. “Their quality of color and form will interest those for whom the non-representative character of this school of modern art has no terrors,” declared a New York Times review of Rivera’s paintings at the Modern Gallery.

Meyer, clearly, was not terrorized. “For Agnes Meyer to buy a Cubist picture at that moment in time, as an American, was extraordinarily radical,” said Leah Dickerman, who directs editorial and content strategy at the Museum of Modern Art in New York. Dickerman, who co-curated a 2004 Rivera exhibition at the National Gallery of Art, pointed out that Meyer acquired the painting long before Rivera had caught on in the US; he ultimately became well-known not only as a painter, but also as a Communist. “It was a bold step.”

Meyer eventually gifted “No. 9, Nature Morte Espagnole” to her daughter, who seems to have also inherited her mother’s stomach for making audacious choices — a recurrent theme in the film. Graham grew up around the painting and kept it for life, before bequeathing it to the National Gallery of Art in 2002.

With all this in mind, the painting seems unexpectedly apt in The Post. Katharine Graham was an upper-class socialite who hobnobbed with presidents, and with Robert McNamara, the Secretary of Defense who commissioned the Pentagon Papers. Diego Rivera, by contrast, espoused Communist politics and championed the working class. But as the film reminds us, regardless of her dinner party guest list or her inherited wealth, Graham was capable of revolutionary action. She made bold decisions about what to put in her newspaper. And she made bold decisions about what to hang on her wall.