Political Art Exhibitions in Ukraine Face Attacks and Censorship

In December, a professor at the National Academy of Arts in Kyiv, Ukraine damaged a student's artwork depicting the Russian army as phalluses. This follows a number of attacks on political artworks by rightwing groups across the country.

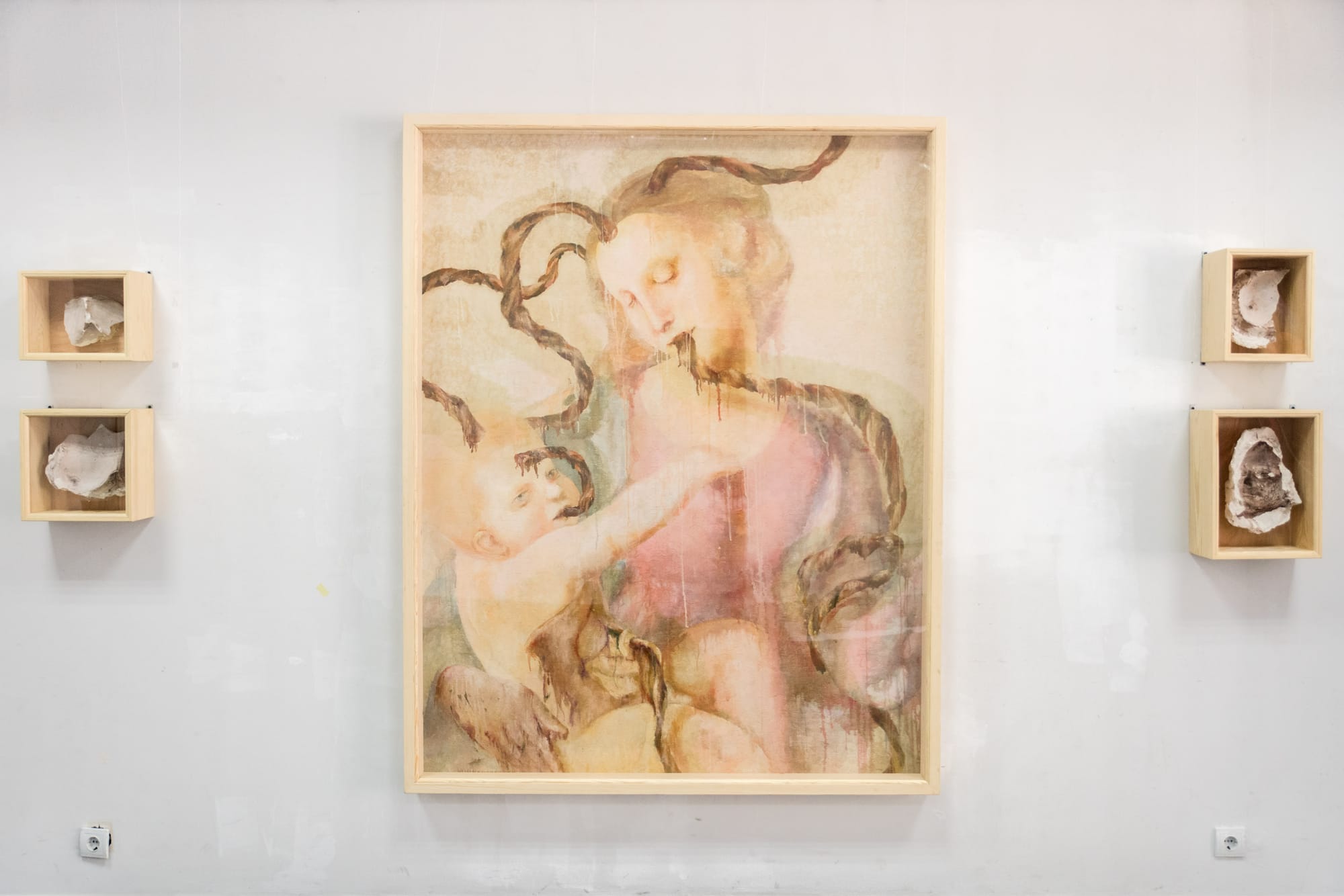

In December 2018, the work of the emerging artist Spartak Khachanov was destroyed at the thesis show of the National Academy of Arts in Kyiv, Ukraine. Khachanov had made a large-scale sculptural installation depicting a militarized parade of phalluses in the hall of the academy to reflect on the Russian invasion in Ukraine. The pacifist installation was condemned by Vladimir Kharchenko, a professor at the academy who considered it inappropriate for the sensitive topic of the war to be displayed in such an ironic way. He subsequently expressed his critique by seeing to the physical destruction of the sculptures. As a result, the artist (a refugee from Donetsk, Ukraine who traveled in Kyiv to study art) was also expelled from the academy.

On the day this was decision taken by the director, a paramilitary nationalist group arrived to threaten Khachanov and locked him inside the university for several hours. Khachanov is now in an art residency in Finland, but the academy attempted to retain his sculptures, claiming they were the property of the institution. This is believed to have been done in order to prevent Khachanov from showcasing his work in Berlin in February 2019.

While the situation at hand may seem shocking to some, the National Academy of Arts in Kyiv is known for its conservatism. For example, no classes of new media, installation, or performance art are given, and the director of the academy, Andriy Chebykin, has held his position for 30 years.

However, this is the first time the academy’s traditionalism has been met with violence inside the walls of the institution, provoking a wave of discussion in the Ukrainian and Eastern European media. The professor who initiated the destruction of the works claimed in an interview to the Ukrainian press that the anti-military content of the work and the representation of war as a contest of masculinities seemed offensive to him in the context of the ongoing Russian aggression, calling it an insult to Ukraine’s necessity to defend itself.

The case of Khachanov is one of the symptoms of a larger problem. Paramilitary groups, the most active of which is called C14, have existed as a form of “art critics” since 2009, when they first burnt down the Gudimov Centre for its presentation of a book with a provocative name: 120 Pages of Sodome. Since then, they have intended to impact Ukraine’s cultural life, censoring the topics of gender, sexuality, and politics in art.

In April 2018, the exhibition Vykhovni Akty (Educational Acts), organized by Alyona Mamay and Valeria Zubatenko, was shuttered on its opening day. The show, which took place at a gallery affiliated with the National Pedagogical University in Kyiv, focused on violence employed by rightwing groups, with some works dedicated to the LGBT community and their uneasy situation in Ukraine, and other works reconsidering the topic of identity and violence.

Prominent Ukrainian artists, such as Anatoly Belov, Nikita Kadan, and Lada Nakonechna, contributed works. This exhibition was condemned by the same C14 group that acted in the case of Khachanov.

The co-curator of the exhibition, Alyona Mamay, commented on the situation to Hyperallergic, saying:

The vice rector of the university closed it, using the letter from a group of ten students (belonging to the aforementioned rightwing organization) that the exhibition contains obscene images and those that offend state symbols. After the exhibition was closed, the student group brought the works to the police station claiming that “these works don’t belong to the university.” The works by Nikita Kadan, Lada Nakonechna, my own works, and those by other artists are still there. […] There is no such dress that is possible to wear in order to avoid the threat of rape, and there is no such artwork that is possible to make in order to avoid the threat of censorship.

After the artworks were confiscated by police, they were never returned to the artists.

To name a few more cases, in May 2012, an exhibition of photographs by Eugenia Belorusets called Svoia Kimnata (A Room of My Own), which focused on LGBT families in Kyiv, was destroyed one day before its closure. The attackers lightly wounded the exhibition’s security guard and tore apart the photographs. The police never reacted to requests for a proper investigation for either case.

This is a particularly insidious type of censorship that has become increasingly common in Ukraine. It is not led by the government, but rather the role of “censors” is taken by the informal groups that play the offended public fighting for traditional values, and these actions are actively supported or ignored by authorities. Belorusets told Hyperallergic she believes the root of the problem is the unclear status of contemporary art in Ukraine, which “balances on the edge between the legal and the acceptable.” She also points out the absence of a museum of contemporary art in Kyiv and the city’s lack of display spaces and archives.

In February 2017, an exhibition of “anarchy” works by David Chichkan Vtrachena Mozhlyvist (The Lost Possibility) was violently attacked. Part of the works were completely destroyed, others defaced.

Recently, at a talk by sociologist Anya Hrytsenko, which focused on the participation of young people in right-radical organizations, an aggressive group stopped the lecture. In a remarkable, almost satirical gesture, the representatives of the group filed a complaint to police against the lecturer according to the article of the Ukrainian Penal Code that focuses on the discrimination based on to nationality, religious views, and other identities — the same article that is used by LGBT activists to report hate crimes. Hrytsenko told Hyperallergic: “What really interests them is not art; it is gender.” They aim to trigger media attention; therefore, they act for an effective image, using visual culture as a target.

All these actions contribute to the creation of an image of there being a human rights crisis in Ukraine and thus can be used to legitimize Russia’s claims of the rise of the rightwing groups in Ukraine and its need to intervene “to defend Russian speakers” (though many of these Russian speakers condemn such intervention). While the state of human rights in Ukraine is otherwise fairly good, the media image created by such pointed actions depicts the state as deteriorating.

In 1999, Cold War historian Frances Stonor Saunders coined the term “cultural Cold War,” to indicate when art and culture become the ideological battlefield between two political systems. But now, an actual war between Russia and Ukraine has opened a cultural “hot” battlefield. Despite the virtual channels of disseminating information, this battlefield is very real. The selective aggression of the self-appointed censors uses media as a platform to distort social context and manipulate public opinion about culture, particularly the arts.

Ukrainian art finds itself unwillingly engaged in a media project that presents a threat to the state of democracy in Ukrainian society. If LGBTQ rights are slowly improving due to the public support often bolstered by visual culture, the art scene, being a powerful producer of political images, often falls victim to attacks in their unregulated “cultural war.” The educational institutions in Ukraine involved in the conflict suffer from a kind of a Stockholm syndrome, being unable to negotiate with the demands of groups that aim to limit the free expression of the artists, and, at the same time, are rigorous defenders of their own violent actions. This attitude encourages apoliticism in art, which in turn effects arts education and the development of artistic practices in Ukraine, spreading the fear of censorship by violence.