A Photographer's Intimate Infinitude

David Lebe has often relied on alternative photographic processes to create powerful depictions of queer bodies.

PHILADELPHIA — A photograph slices infinity into an instant. Some photographers thrive in thousandths of a second. Others seek out durations of a few seconds or more. David Lebe, in the course of his five-decade career, has frequently prolonged exposure times beyond a quarter of an hour. His images do not capture decisive moments but, as he once said, give us “decisive twenty minutes.”

Take “Angelo in Robe” (1979), a picture that took Lebe 40 minutes to complete. A young man sits on a mattress in a darkened room, one bare foot planted on the parquet floor, the sole of another exposed to the viewer. The photographer used a flashlight to outline the man’s face, hair, limbs, and folds of clothes. Fusing the visible with the tactile, Lebe ensconced every part of the model’s body in a halo of light.

The image is part of the artist’s first retrospective, Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe, currently at the Philadelphia Museum of Art. Lebe belongs, along with Peter Hujar and Robert Mapplethorpe, to the first generation of gay photographers in the United States who openly explored homosexuality in their work. The photographer has often relied on alternative photographic processes to create powerful depictions of queer bodies. His work grapples with sexuality, identity, illness, and death, and attests to a lifelong privileging of process and experimentation over technology.

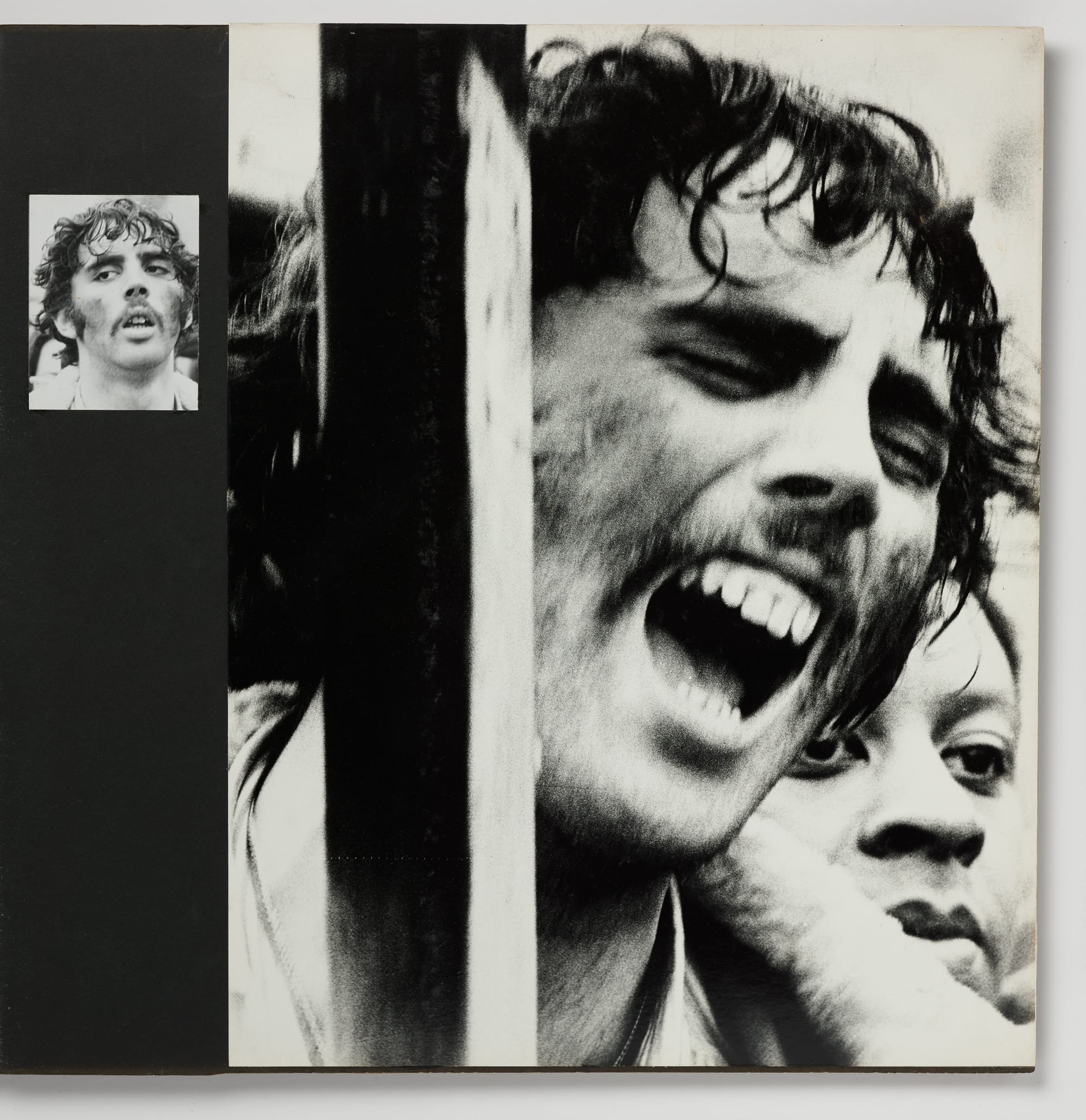

Born in New York, Lebe settled in Philadelphia in the late 1960s and studied at the Philadelphia College of Art (now the University of the Arts), where he subsequently taught photography until the early 1990s. Encouraged to break with photographic conventions by his influential teachers, Ray K. Metzker and Barbara Blondeau, he chose to work with a pinhole camera. The oversized apparatus had multiple pinholes and required exposure times lasting many minutes. By opening and closing the apertures at different times, Lebe could create a single, scroll-like print of the whole event, transmuting it into a dreamy collage of social interactions.

Seeking more direct contact with the act of image-making, Lebe began to hand-color his pictures in the early 1970s. Eventually, the artist did away with what he called the “abstractions of camera technology” and started to experiment with photograms (photo-images created without a camera). Lebe placed dried plants onto light-sensitive materials and exposed them to light. He created elaborate plant arrangements, converted negative prints on a black background into positives, and hand-colored his images. The unique process transformed the photograms into surreal painterly abstractions. In “Landscape #33,” red-glowing trees float through a dark, star-studded cosmos; in “Garden Series #3,” a leafy flower with three stems rises toward a moody, hand-colored sky. Each image is a bizarre, alluring dreamscape.

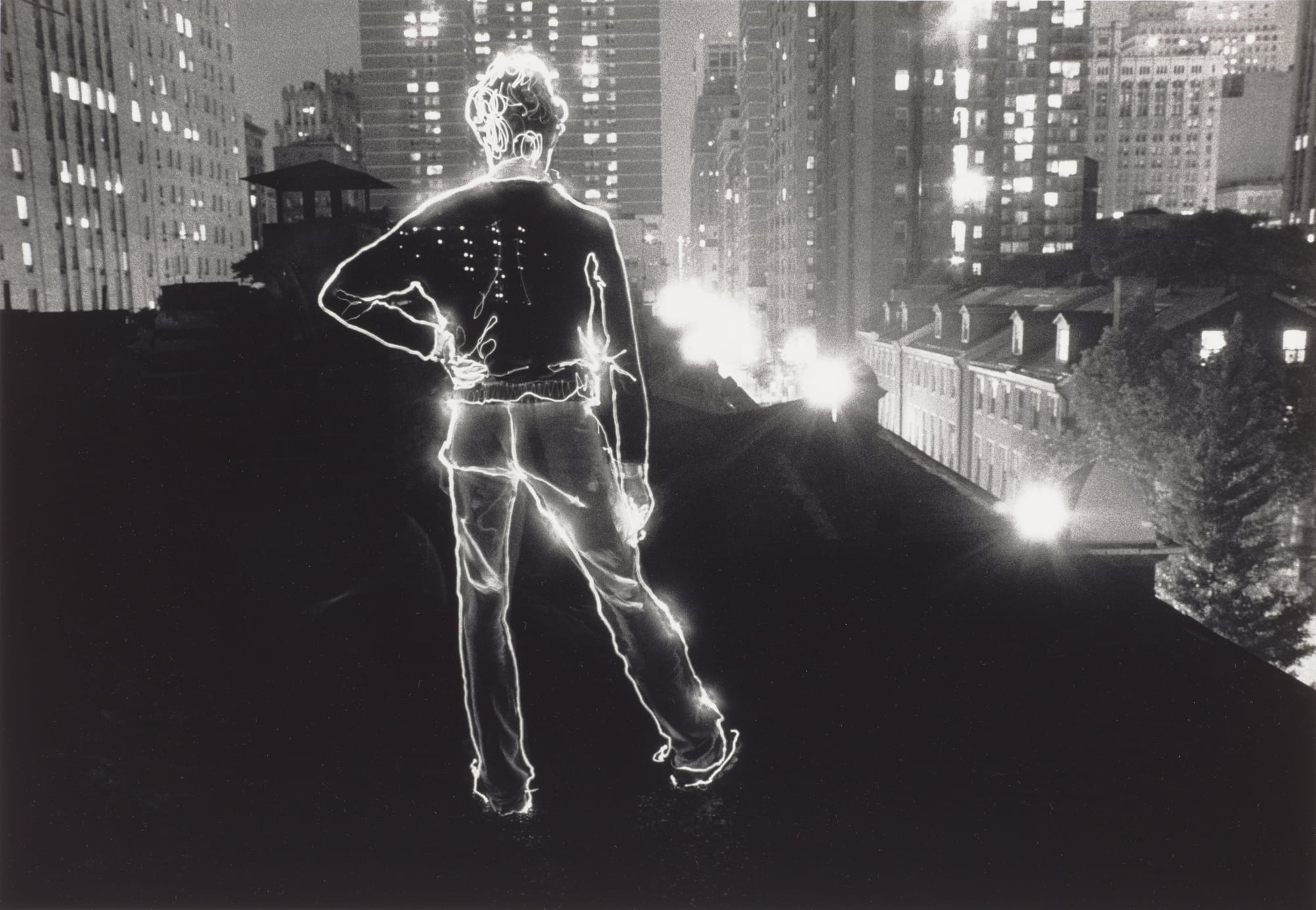

After coming out as a gay man in the mid-’70s, Lebe turned his artistic attention to queer experience and the male figure. Using a flashlight and conventional camera set on a tripod, he created light drawings of friends and lovers by tracing their bodies in dimly lit rooms. Braiding the art of photography with the art of drawing, the artist caressed his models with light, sketching their faces, limbs, and genitals, and at times adding small fictional details such as luminous arcs touching the model’s bodies. Demarcating the boundaries of desire, light preserves the men’s traces while eliciting a feeling of touch.

As Lebe continued making photograms and light drawings, the carnal and the vegetal often fused. In “Seth,” a nude man sleeps on a floral tapestry. Above him, a small, leafy branch floats through the morning sky, which the artist hand-colored to resemble a sunrise. The man and the plant seem to drift through the same dream-time, a realm where bodies and botany are equally precious and transient.

As the AIDS crisis of the 1980s ravaged the gay community, Lebe began to lose friends and was himself diagnosed with the illness in 1988. At this point, as he began to respond to the epidemic, his work became more sexually explicit. The artist photographed men pleasuring themselves and enjoying their own bodies. For five years, he recorded the gay porn star and writer Scott O’Hara (1961-1998) as he slowly wasted away from AIDS. In one picture O’Hara performs an auto-fellatio, with “HIV +” tattooed on his arm. The images are an act of defiance toward mainstream culture and its neglect of and hostility to the epidemic. Lebe’s Scribbles series depicts urn-like vases emanating hand-drawn spirals of light, like departed spirits. All that is visible of the human presence in the dark are feet. Lebe said in the exhibition’s catalogue that the pictures are “a kind of celebration of the spirits of so many who had died.”

In 1993 Lebe and his partner, Jack Potter, who was also diagnosed with AIDS, left Philadelphia and moved to a country house in the Hudson Valley. Isolated from the world, the couple adopted a holistic life style. Neither expected to live for long. In his series Morning Rituals (1994), Lebe documented Potter’s ordinary morning activities: shaving, showering, looking into the mirror, taking medications, dressing. The tender, moving pictures celebrate the preciousness of each moment shared by the couple in the face of mortality. Lebe and Potter were able to gain access to HIV combination drug therapy in 1996 and both still live in the same home today.

The exhibition, painstakingly curated by Peter Barberie, illuminates a desperate chapter in American history. It closes with Lebe’s recent digital images of shadows cast by plants and his own body. Quiet and meditative, these pictures are an affirmation of life’s everyday pleasures in the present moment by an artist who dedicated his artistic career to the prolongation of longing and the preservation of what he loved.

Long Light: Photographs by David Lebe continues at the Philadelphia Museum of Art (Perelman Building, 2525 Pennsylvania Avenue, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania) through May 5. The exhibition was curated by Peter Barberie.