Isidore Isou's Radical Quest to Reinvent Language

A sweeping retrospective at the Centre Pompidou surveys the work of the Romanian-born artist who founded the avant-garde Letterism movement in 1940s France.

PARIS — Indefatigable theorist, poet, painter, filmmaker, playwright, megalomaniac intellectual, and avant-gardist of avant-gardists, Isidore Isou (1925-2007) never fails to flummox the senses with the cumulative complexity of his work. A sweeping retrospective at the Centre Pompidou, built around an archival treasure trove recently acquired by the museum, presents an opulent and conceptually challenging body of Isou’s paintings, films, objects, sounds, drawings, and writings, which encompass all means of lexical and phonetic notation.

Born Jewish in Botoșani, Romania in 1925, Isou survived World War II and, after reading the likes of Mallarmé and Flaubert, managed to clandestinely leave his home country for France at age 20. He arrived in 1945 in Saint-Germain-des-Prés, where he encountered numerous members of the French intelligentsia, including André Breton, Tristan Tzara, and, most importantly, the young poet/artist Gabriel Pomerand. Together with Pomerand, Isou sparked the creation of the Letterism movement (a term he coined in 1942), which had theoretical roots in the Surrealist literary tradition and the avant-garde phonetism of Dada. Letterism took as inspiration the phonetic sound poems of Tzara, Raoul Hausmann, and Kurt Schwitters, whose nihilistic goal was to trigger the collapse of national communication, as it was precisely what led to World War I. Unlike the Dadaists, however, Letterists focused on blocks of rhythmically organized letters, abstract symbols, and sounds; for Isou, Letterist poems were akin to atonal, rhythmic musical compositions.

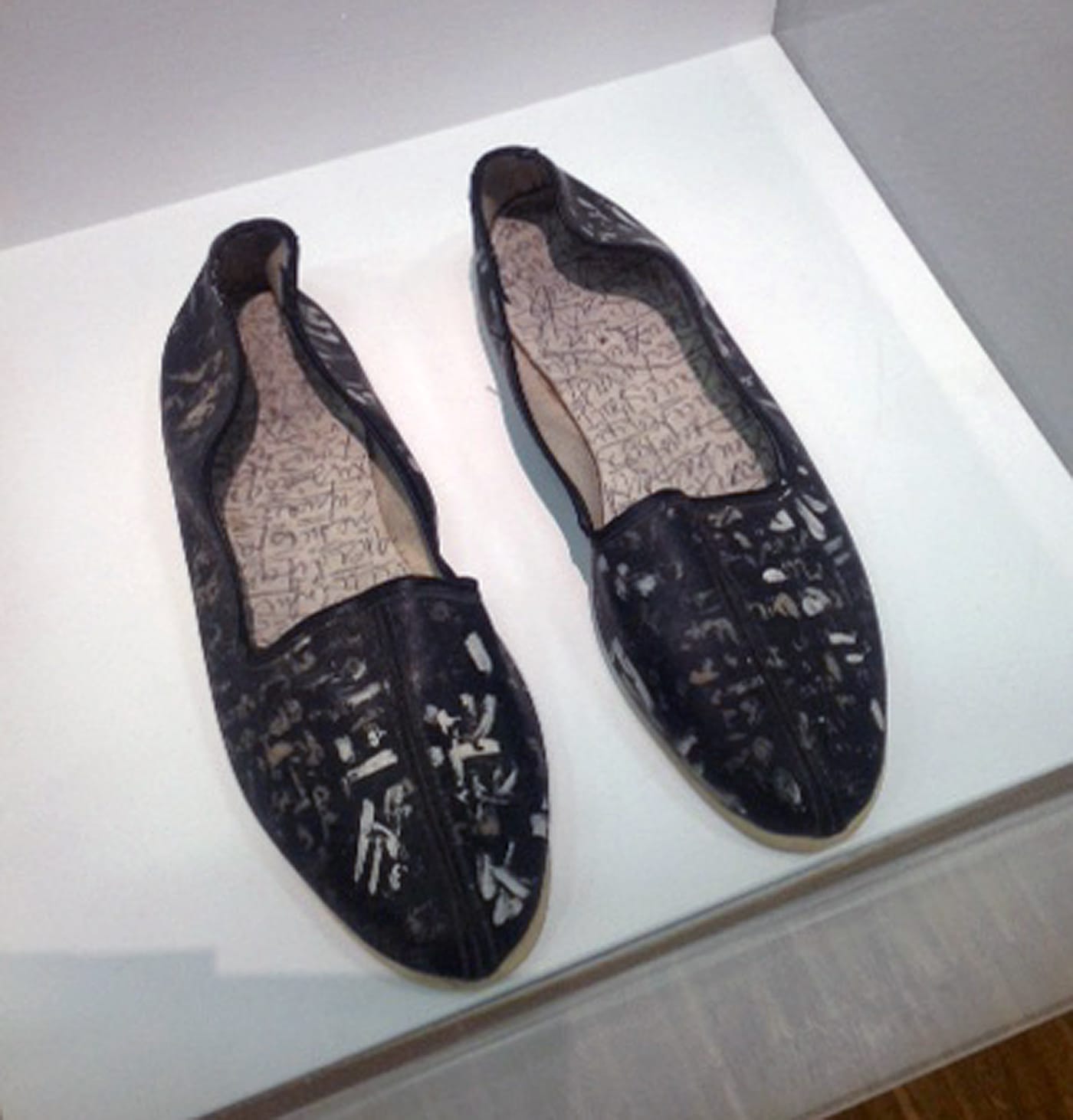

Letterism, therefore, was an optimistic endeavor: an innovative process by which humankind might develop a new means of communication not necessarily based on words. Simultaneously theoretical and practical, aesthetic and political, the Letterism project was a gesamtkunstwerk (total-art) that strove to free society from its reliance on conventional linguistic structures. Isou envisioned a formal revitalization of art and life through refiguring the power of the letter, a revitalization so vast as to cover the land: a point cheekily concocted by Isou’s “Sculpture Hypergraphique (Polylogue)” (1964), a pair of what appear to be black Chinese-style slipper-shoes that have been marked with hypergraphs (scribbly abstract letterforms) from toe to heel.

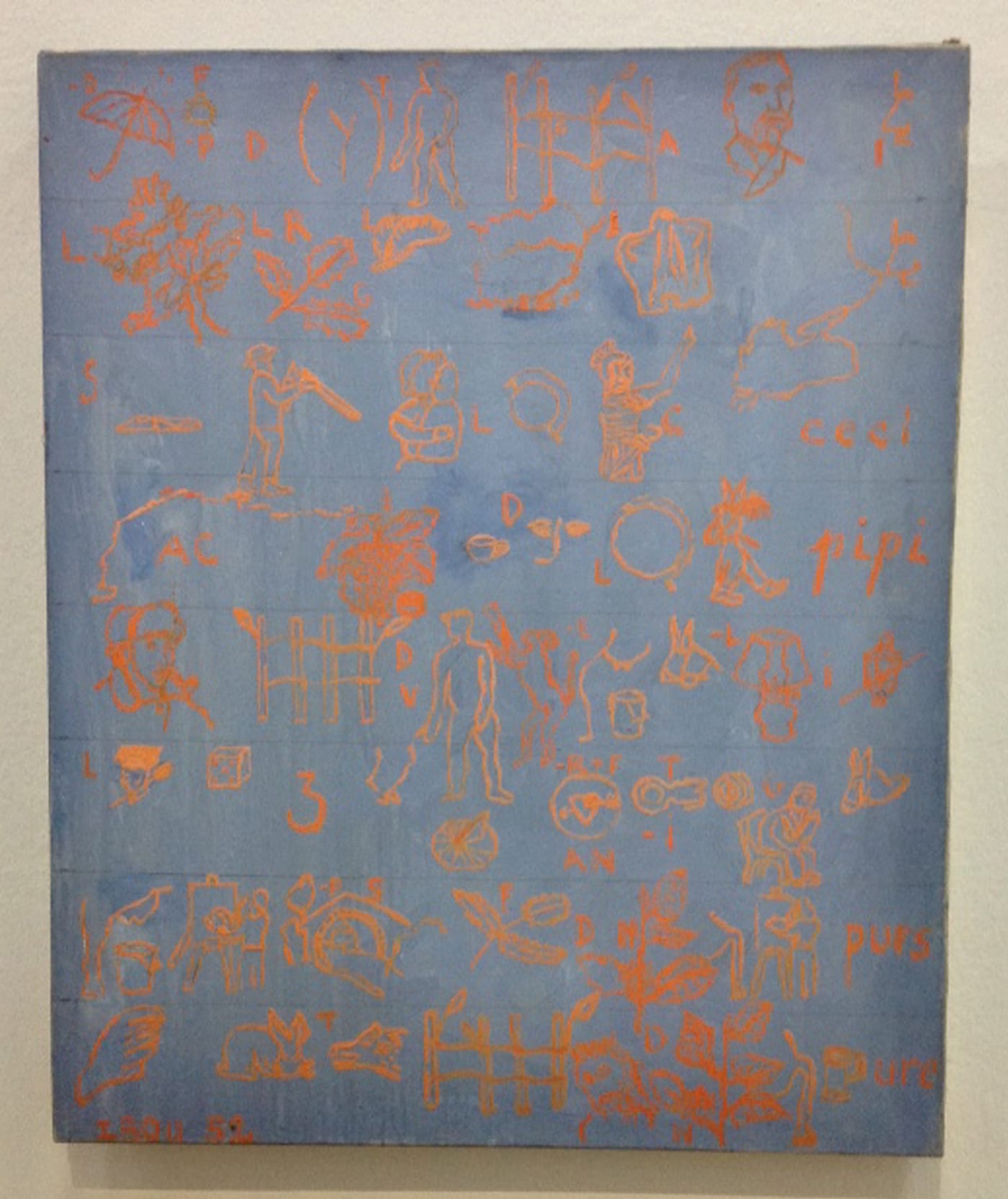

Isou’s invented letter-like symbols are not to be seen as carrying a useful message, but solely as the object of semi-abstract art: creating a third visual way after the figurative and the abstract. This is nicely illustrated by the inclusion of an Orson Welles interview with Isou that was excerpted from Welles’s 1955 documentary film Around the World with Orson Welles.

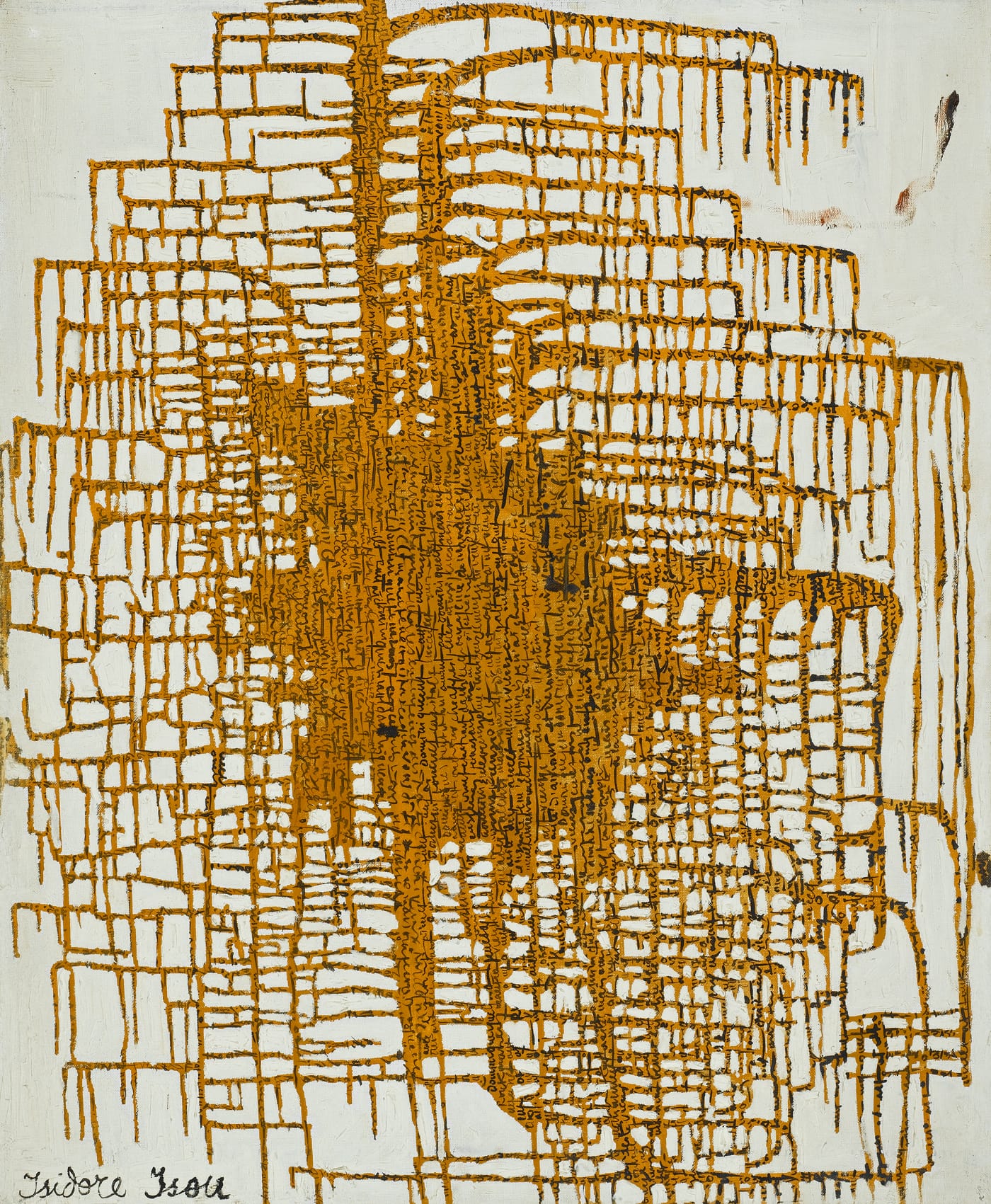

Certain of Isou’s Letterist poems achieved notoriety not for their performed vocal dexterity and lyricism, but because of the quality of their graphic design, as seen in his hybrid photo-paintings series “Amos ou Introduction a la metagrapholgie” (1952). Isou’s rhythmic linguistic-conceptual approach to painting often yielded gratifying results, as seen in “Incrustations dans le Brouillard” (Inlays in the Fog, 1961), a creamy fog painting embedded with a whirl of scribbles; “Réseau centré M67” (M67 Centered Network, 1961), a tan painting that drips in every direction; and the conceptually challenging “Telescripto-Peinture” (Telescripto-Painting, 1963-1987), basically some sort of telematic machine, resembling a typewriter, designated to be a painting in its own right.

On January 21, 1946, Isou attended the première of fellow Romanian Tzara’s play La Fuite (The Escape) at the Vieux-Colombier theater. In the tradition of Dadaist provocation, he began bellowing, “Dada is dead! Letterism lives!” At the end of the play, Isou jumped up on stage and, after spouting his Letterist ideas, read a few of his early poems. Even given Letterism’s relentless criticism of the mediocrity of the other radical French intellectuals, in 1947, with the support of Jean Cocteau and Jean Paulhan, Isou published in La Nouvelle Revue française his grand theoretical proposition, Introduction to a New Poetry and a New Music, in which he laid the groundwork for Letterism and metagraphy (métagraphie). In these literary innovative approaches that use graphic compounds not recognized by any given dictionary, Isou described what he saw as the golden path of decomposition which French poetry had traveled starting with Charles Baudelaire. Isou declared that “the letter” be the final stage of this process of decomposition-refinement — and more generally that “signs” represent the possible foundation for a total renewal of the arts.

In 1976, after Letterism went in and out of vogue, the sum of Isou’s reflections were compiled in an enormous 1,390-page theoretical book called La Créatique ou la Novatique (Creatics), the manuscript of which is on view at the Pompidou. In it, Isou put forth his model of human understanding in contrast to what he saw as a banal world of mere copyists caught in a state of general vulgarization.

Besides the paintings, the other highlight of the show is a large projection of Isou’s 35mm 1951 experimental, revolutionary film Traité de bave et d’éternité (Treatise on Venom and Eternity), which caused a scandal at the 1951 Cannes Film Festival. The film begins with Isou wandering about the Saint-Germain-des-Prés while his disembodied voice combatively asserts his Letterist theory. Later, in an act of détournement, found newsreel celluloid footage of factory workers and the French occupation of Indochina are spliced in and crazily attacked with the creative-destructive technique of painting out and scratching out faces. A virtual Letterist film manifesto, the film is so compelling that it greatly influenced American avant-garde filmmaker Stan Brakhage. As can be seen in this snippet, and in the original trailer, the film savagely attacks cinematic conventions by creating what Isou called “discrepancy cinema,” in which the soundtrack has little to do with the accompanying images.

Isou’s theoretical artworks offer propositions that are in line with current artistic reflections on our contemporary situation, in which digital image technology heightens our sense of excess and visual noise. Time has proven Isou’s idea of poetic graphic plasticity, with its urge for decomposing fixed forms, insightful and highly relevant.

Isidore Isou, curated by Nicolas Liucci-Goutnikov, continues at the Centre Pompidou (Place Georges-Pompidou, 75004 Paris, France) until May 20.