How Humans Betray the Environment and One Another Throughout History

Some of the best films at the Montreal International Documentary Festival explored themes of wasted potential and the relationship between humanity and the planet.

At this year’s Montreal International Documentary Festival, one recurring theme was wasted potential. Lemohang Jeremiah Mosese’s debut feature Mother, I Am Suffocating. This Is My Last Film About You., plays a trick on the viewer. Taking place in an unnamed country, a narrator describes their frustration with their mother, recalling some simpler or happier moments, but mostly accusing her of irresponsibility and indifference. It takes a while, but eventually it becomes clear that the “mother” is Mother Earth, and that this is a purposeful blurring of the personal and the political. Throughout the 75-minute film, we watch as a woman carries a gigantic cross through the streets of a village, struggling immensely but determined to keep going. The film verges on being overly ambitious, making an argument about the religious and historic failures of the human race via somewhat overwrought images and music. And yet there is something effective about the approach, bringing the betrayal of both sides into focus, conjuring a world bereft of potential.

In Fordlandia Malaise, director Susana De Sousa Dias narrows the scope somewhat by taking drones to an industrial town in the Amazon founded by Henry Ford in 1928. For a time, it was developed in earnest, intended to be a major supplier of rubber. It didn’t last long. Today, Fordlandia is a ghost town, its barren nature made all the more stark by the black-and-white cinematography. In voiceover, we hear stories from indigenous people and current-day citizens who continue to hold on in Fordlandia, emphasizing the indifference of colonial powers to the lands and people they oppress. Originally conceived as a utopian vision of what a working town could be, Fordlandia’s dystopian present demonstrated by director De Sousa Dias is a reminder that this was always an empty promise.

Our relationship to the environment is also key to technocratic development around the world, as Big Tech grows more powerful and “smart technologies” and solutions become a governmental and cultural priority. This is deeply felt in Bangalore, India’s Silicon Valley. In director Sindhu Thirumalaisamy’s The Lake and the Lake, we see how this plays out with the urban lake Bellandur, which is massively polluted (mostly with sewage) and creates a toxic white foam that floats in the air like the plastic bag from American Beauty. And yet, like in Fordlandia, people still live by the lake, even despite the foam’s potential to catch fire and cause damage. The alluring promise of a Silicon Valley infrastructure survives, and yet one citizen is overheard making fun of the fact that Bangalore landed in the third tier of “smart cities” around the world. This disillusionment is reflected in the film’s depiction of the lake itself, a constant reminder that “progress” can be corrosive. It’s like the problems encountered by San Francisco, which everyone wants to emulate. Who actually benefits? How is the natural world being impacted? What is the cost of progress? Thirumalaisamy doesn’t have any answers, but she offers a powerful rebuke to the cult of tech.

Werner Herzog’s latest documentary, Nomad: In the Footsteps of Bruce Chatwin, is a personal and loose film about his friendship with Chatwin, the renowned author and adventurer who died of AIDS in 1989. His is a familiar tragedy of wasted potential. The film is also an opportunity for Herzog to look back on significant moments in his career, including projects adapted from Chatwin’s books, such as Cobra Verde (Chatwin also visited that set as he was getting increasingly sick). Herzog talks about how similar Chatwin’s outlook on life was to his own — a kindred spirit invested in discovery and travel. More than once, he insists to an interviewee that he is not the protagonist of the film, and yet as is his style, his voice is our throughline. We come to understand less about Chatwin himself than about his relationship with Herzog. The result is a bit haphazard and unfocused, with the film randomly broken into chapters to give a feeling of structure where none exists. Yet early on, Herzog states that he hopes to engage in a series of “erratic quests” in honor of his friend, and so the approach works, particularly in the face of Herzog’s concerns over humanity coming to an end via environmental crisis. He concludes that we must do as Chatwin did: walk, explore, and connect to nature and one another.

Another common theme at the festival was displacement, which is palpable in Félix Lamarche’s experimental short Terres fantômes, about a group of villages in rural Quebec that were forced to move to the coast during the 1970s due to a new planning policy. The ghostly images alongside the remembrances of former residents make for a distinctly melancholic experience. What is home? What does it feel like? Some of these characters seem to have carried their old lives with them, while traces of them remain back where they come from. As we can see across many of these films, people have deep attachments to their land, which in turn makes them extremely adaptable. Come what may, this is home. And yet the characters in Terres fantômes were forcibly uprooted, given no choice but to sever that connection. These wounds still fester, and there are hints of that trauma being passed from one generation to the next. Having the chance to speak their history seems like a small catharsis.

In legendary director Alanis Obomsawin’s latest film, Jordan River Anderson, The Messenger, a baby boy is “displaced” from the opportunity to go home after his birth due to a serious muscular condition. Sadly, Jordan was never able to leave the hospital, due to the lack of an agreement between the federal and provincial governments, dying there at the age of five in 2005. Obomaswin has charted indigenous life, culture, discrimination, history, and oppression for decades in Canada, and this latest is a story of broken bureacracy. The film is about the immense legal struggle to establish “Jordan’s Principle,” which intends to make government-funded public services as available to indigenous children as they are to everyone else. The film itself is typical of Obomsawin’s style, unobtrusive and straightforward, interested above all in knowledge-sharing and consciousness-raising. Hers is an art of advocacy that lingers on moments of beauty and turns agitprop into a tender (but angry when appropriate) exercise.

Jessica Bardsley’s Goodbye Thelma is a short about a woman traveling alone, a singular sort of displacement that brings with it danger, threats, and a general paranoia. This is intercut with scenes from Thelma and Louise, who travelled together, yet even then were faced with horrific encounters. Everything is wrong, though. The scenes of Susan Sarandon and Geena Davis are washed out, turned into their negatives, while the story of our lone traveler is not told with voiceover but onscreen text. The result is a double narrative of isolation and fear, but also power. One gets the feeling that reality and fantasy are blurring purposefully, as everything feels off.

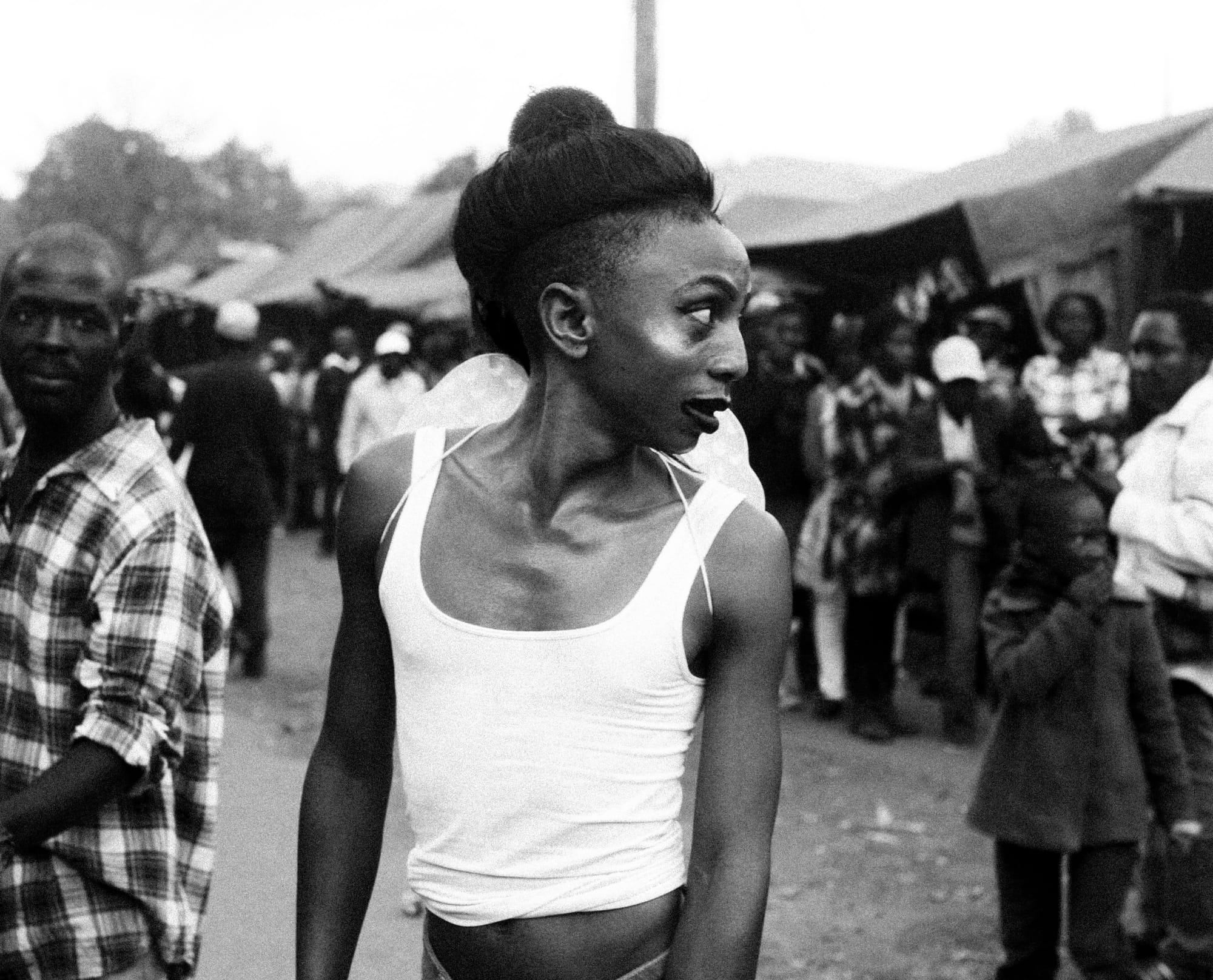

One of the best things I saw was Ja’Tovia Gary’s The Giverny Document (Single Channel). (Hyperallergic has previously interviewed Gary about the film.) Many vastly different elements are intercut, including interviews with black women on the streets of Harlem, a glitch art experiment filmed on location in Claude Monet’s garden in Giverny, archival footage of Monet himself painting the garden, footage taken by Diamond Reynolds after her boyfriend Philando Castile was murdered by a cop in 2016, a dramatic 1976 performance by Nina Simone, and more. This could have been incoherent or unclear, but instead it’s a compelling and affective tonal whiplash. The interviews are variously funny and tragic, as some women claim to have no fear in their bodies or on the street, while others emphasize that they make a point to never walk alone in public (recalling Bardsley’s perspective in Goodbye Thelma). Taken together, the film’s many disparate parts come together as representations of how black women are exploited and how they are resistant, highlighting how much work it can be to feel comfortable being yourself in the world — or more specifically, in this world.

The Montreal International Documentary Festival ran November 14 through 24.