Over 100 Artists Contribute to Benefit Exhibition Foregrounding the Experiences of Detained Children

DYKWTCA (Do you know where the children are?) will travel across the US until after the 2021 election. The works will be offered for $500 each and the full proceeds donated to immigrant advocacy groups.

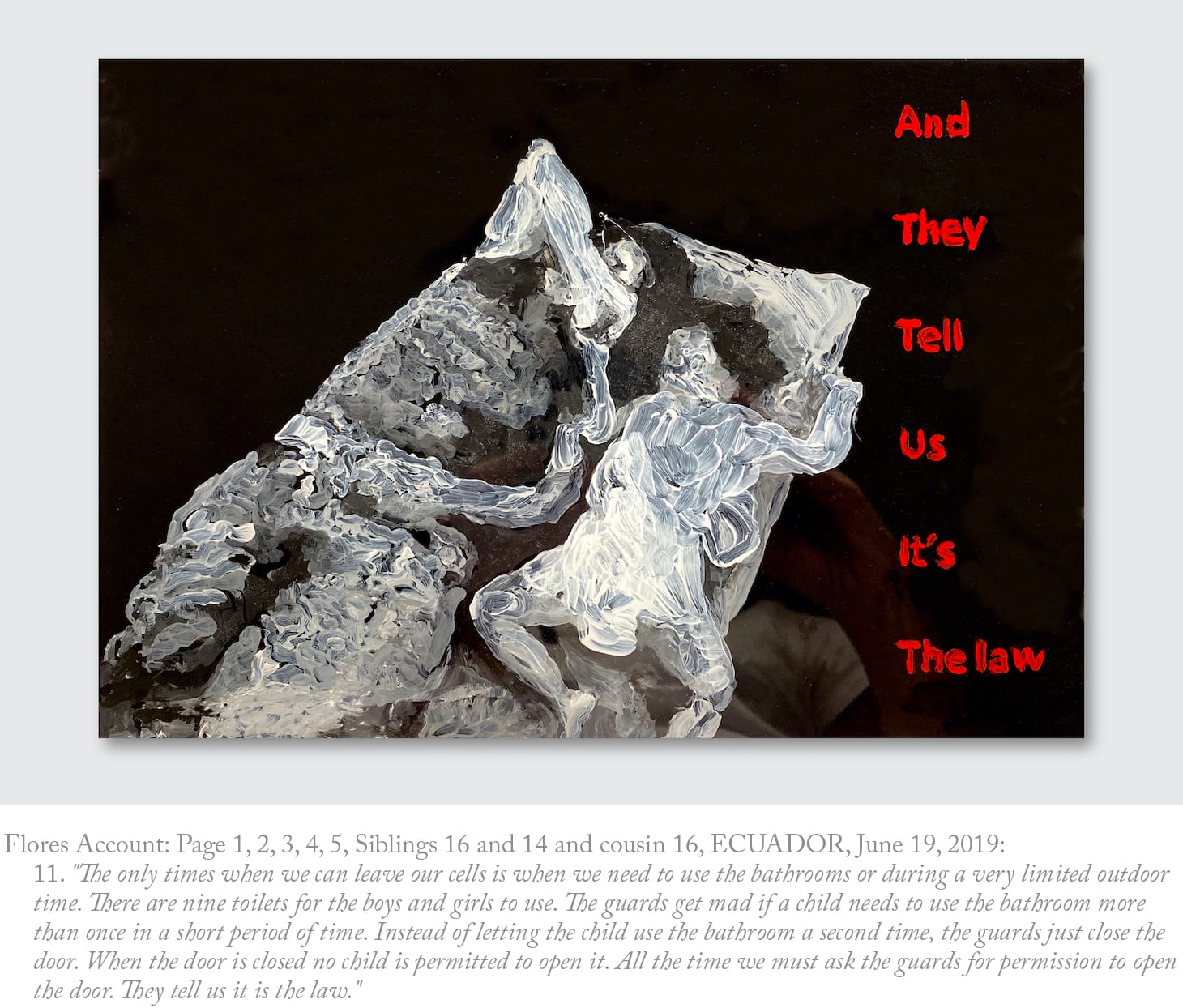

“They tell us it is the law,” concludes the chilling account of three Ecuadorian siblings detained at a Border Patrol facility in Clint, Texas, who describe guards shutting the door if they try to use the bathroom too frequently. In a painting by Jesse Presley Jones, two youth are crammed on a small cot, their silhouettes blurred and distorted by the abyssal darkness that envelops them. Beside them, a text in red letters spells the haunting phrase from the children’s unsettling report.

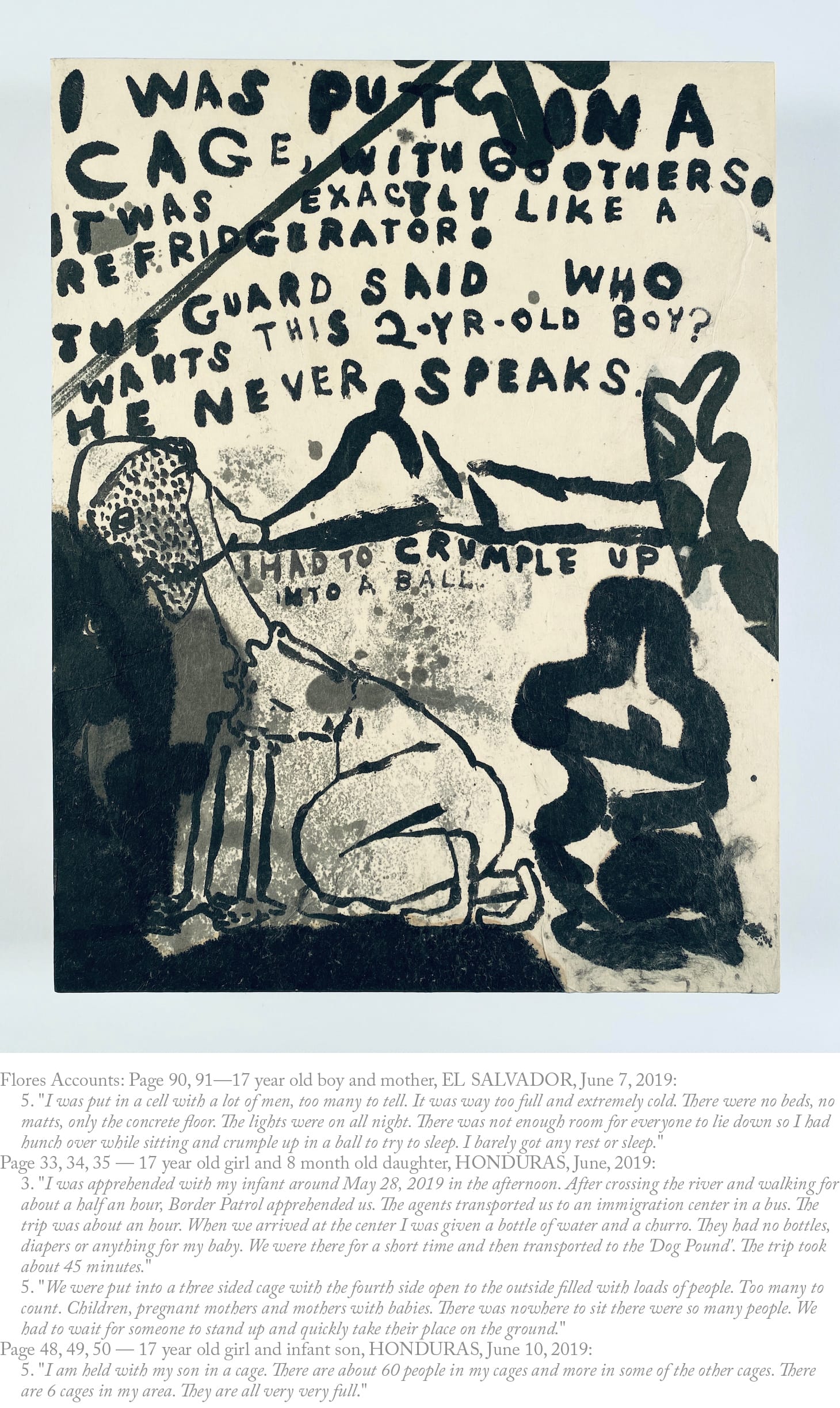

Presley Jones’s work is one of over 100 pieces included in DYKWTCA (Do you know where the children are?), a benefit exhibition organized by artists and activists Mary Ellen Carroll and Lucas Michael. The project seeks to foreground the experiences of children detained and separated from their families at the US border. Leading and emerging contemporary artists, including Julie Mehretu, Pope.L, Amy Sillman, and Lawrence Weiner, contributed works that incorporate or are based on sworn declarations by children at migrant detention facilities. The interviews, conducted by investigators under the Flores Settlement Agreement in June 2019 and shared publicly by Project Amplify, speak to the harrowing and squalid conditions at these centers, where poor hygiene, lack of proper nutrition, and untreated sickness are rife. The traveling show will debut on January 25 at the Corner, a new, non-collecting cultural institution at the Whitman Walker community health center in Washington, DC, where it will be titled When We First Arrived… and curated by Executive Director Ruth Noack.

“The series of works of art will be made available at a set price/donation of $500 and a random selection process that is secure, ordered, and transparent will determine the work of art that one will receive,” explained Carroll. “The transactions will remain anonymous until all of the works are acquired, registered, and transferred, and there is a limit of two works of art per entity or person,” she added. Private foundations will match the sales, and all proceeds will be donated to Innovation Law Lab, Team Brownsville, and Terra Firma/Safe Passage, organizations committed to advancing immigrant rights and providing humanitarian aid to asylum seekers.

“When I read the interviews, which were shocking, I realized that the detainees are being warehoused as goods — beneath even animals, just treated as cold storage,” said Sillman in a press release about the project. “The angry and despairing images entered my work as spills, stains, fragmented objects and marks strewn across empty grounds. I am consciously including these forms in the language of my paintings to reflect these horrific stories. They need to be read, and the feelings they elicit (rage, discomfort, chaos) need to be felt sharply.”

Carroll and Michael began planning the exhibition around two months ago, stirred by the horrific realities uncovered in last year’s investigations and by the urgent need to act. In an interview with Hyperallergic, Carroll said most of the artists they contacted agreed to contribute work to the show, speaking to the power of a specific call to action at a time when many feel powerless in the face of global injustices. “What distinguishes most human beings is the ability to think and act. As artists, the question is what WE can do individually and collectively,” wrote Carroll in an e-mail.

The organizers transcribed the Flores interviews provided by Project Amplify and made them available as searchable PDFs; then artists were asked to read through the accounts and produce a work as a material record of the children’s experiences.

“I realized that those kids could be me, or anyone in my family,” said Boris Torres, a participating artist who emigrated to the US from Ecuador as a child, in the press release. “I think if I had gone through any of the horrible things that those kids are being put through, it would have destroyed me. I think the US is breaking these kids physically and mentally. It is evil. It makes me ashamed of our country, and what America stands for.”

Carroll and Michael’s careful attention to the way the works will be placed reveals their alertness to the pitfalls of the art market and the lives that artworks assume once they land in private hands. The practice of acquiring artworks through charity sales only to resell them at a profit has unfortunately become an all-too-familiar tale in the contemporary art world. (In 2018, for example, painter Cecily Brown took to Instagram to call out a collector who acquired one of her pastels from a Help Refugees UK fundraiser and consigned it to Sotheby’s less than a year later.) By offering the works in DYKWTCA through a random selection process rather than allowing buyers to hand-pick their choice, the show’s organizers hope to discourage and deter the cycle of speculation. The press release stipulates that “the initial donor/owner shall hold the works of art for five years,” and if they are sold before that time, “the proceeds will be split equally between the seller, the artist, and one of the organizations mentioned above.”

Another concern was ensuring each piece and its corresponding Flores account remain together through posterity. To that end, the project has enlisted the services of the digital registry Artory and art advisory and appraisal firm Winston Art Group, who will register the works, and the Flores accounts attached to them. By logging this data permanently using blockchain technology, they aim to ensure the works’ provenance and the children’s stories remain public.

The organizers also stress that participating artists took care not to aestheticize the realities described in the Flores interviews, many of which contain shocking reports of violence and negligence. Instead, the press release for the show insists on the works as a “material history of the atrocities.”

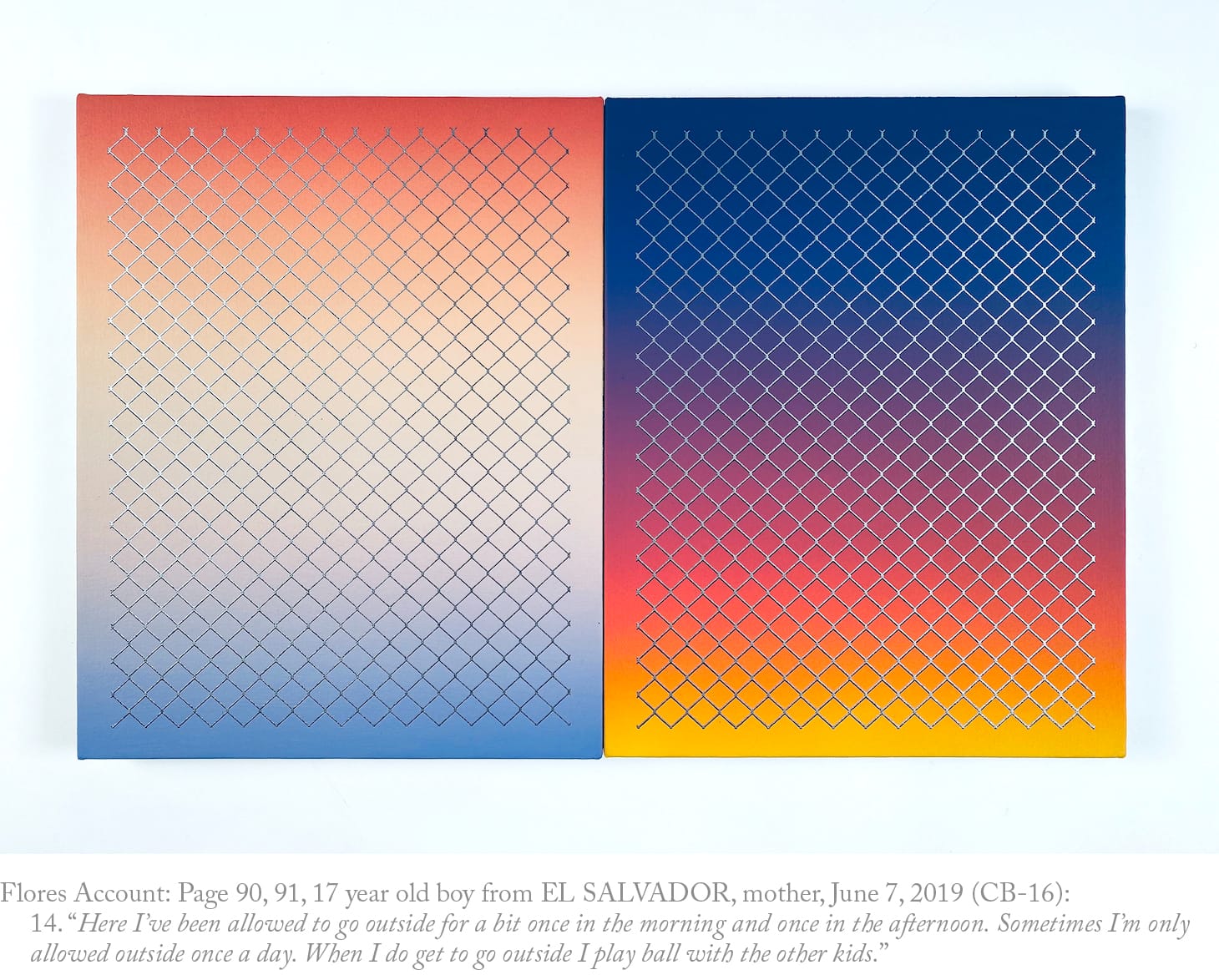

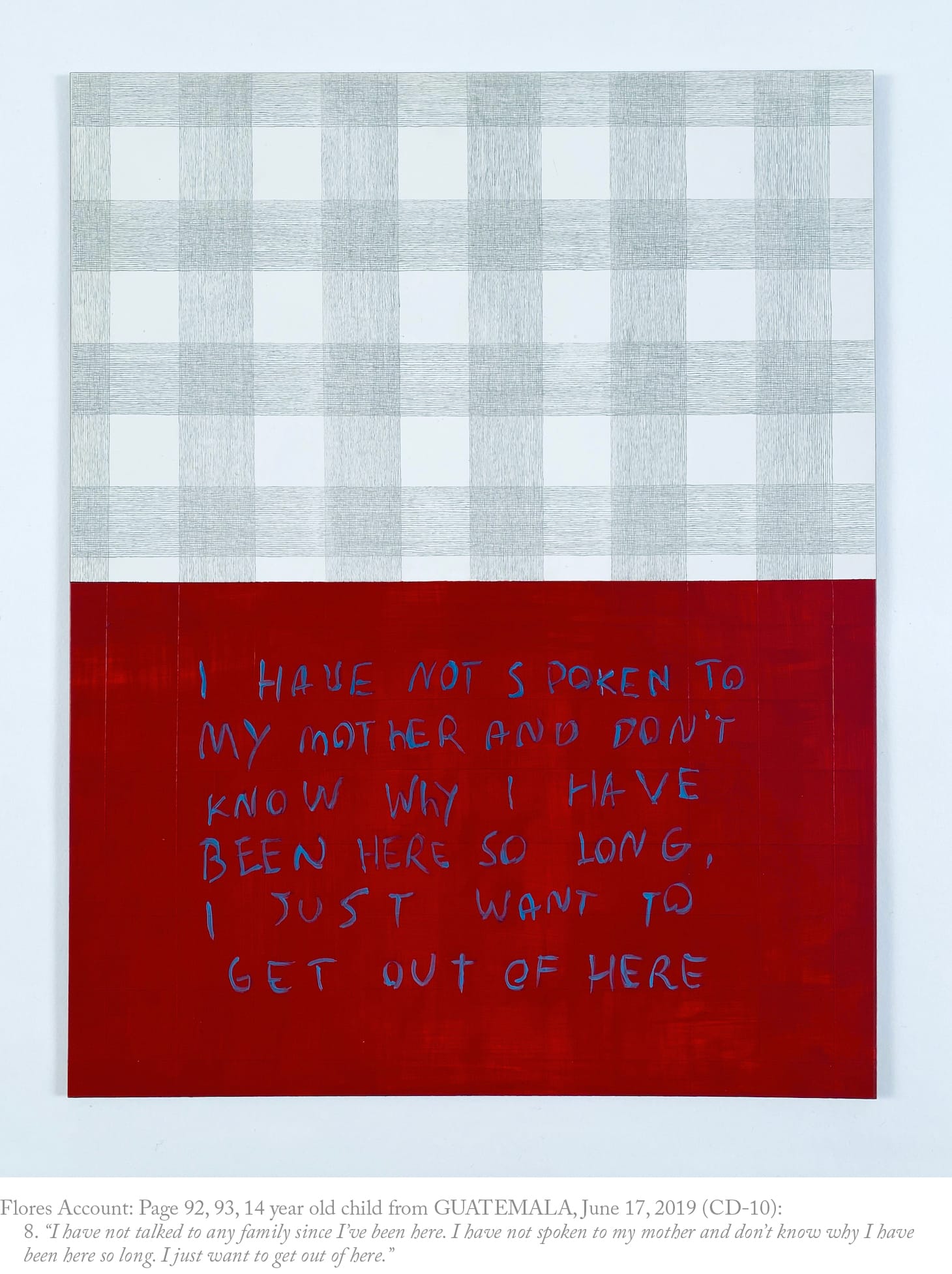

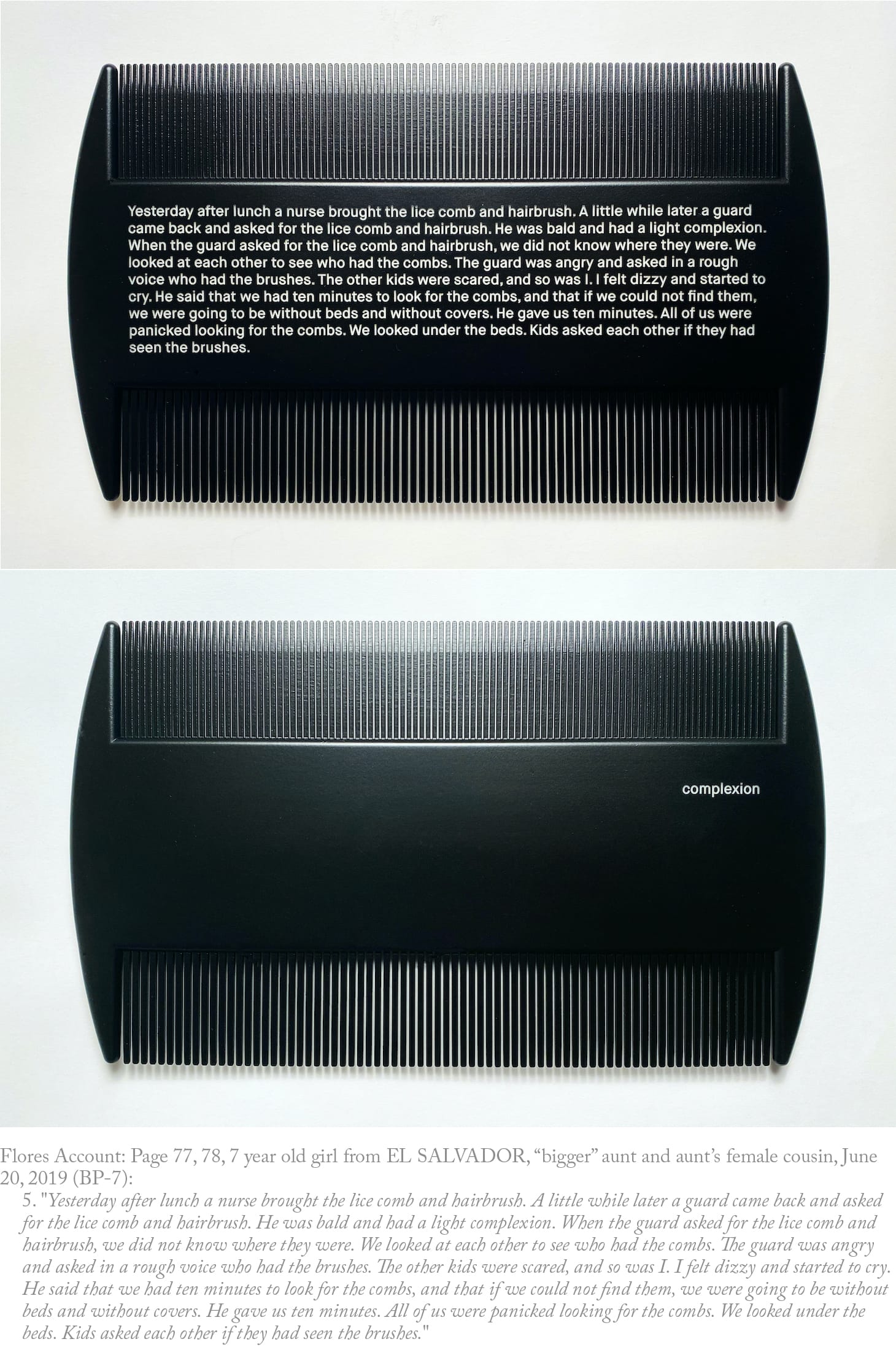

Many of the works in the show are text-based and feature actual excerpts from the interviews, including some by artists who are otherwise known for abstraction. Others combine inventive uses of material to intensify the testimonies. Molly Gochman’s contribution, “Complexion” (2020), consists of a pair of lice combs. One is printed with a detained child’s unsettling story, the other simply with the word “complexion,” alluding to the notable description of a guard’s “light complexion” in the account. Rob Pruitt’s diptych “Sunrise / Sunset” (2019) depicts metal fences against warm- and cool-toned gradient backgrounds. “Sometimes I’m only allowed outside once a day,” reads part of the testimony attached to the work.

“The works become imbued with these accounts,” said Carroll. “What they really do is expand the voices of these kids.”

The Flores Settlement dates back to 1997 and delineates basic standards of care for the holding and treatment of minors in immigration custody. Last August, Trump announced his decision to end the settlement, threatening the already minimal protections to which migrant children are entitled.

The press release for the exhibition notes the history of art institutions supporting refugees for asylum, citing MoMA’s efforts to sponsor artists and other cultural figures escaping from Europe to America during World War II.

“DYKWTCA is an important addition to the lineage of artist-organized exhibitions that push back against state-sponsored racism, torture, and oppression,” Lauren O’Neill-Butler, an independent writer and critic who has been assisting Carroll and Michael with the project’s various tasks, told Hyperallergic. “It’s been an honor to be a part of this and watch artistic activism blossom pragmatically, collectively, and effectively. ”

Following its debut at the Corner, the works will travel to other institutional venues in California, Texas, and New York that have not yet been announced, with the exhibition’s tour concluding in January 2021, after the US presidential election.

DYKWTCA (Do you know where the children are?) is organized by Mary Ellen Carroll and Lucas Michael. Its first iteration, When We First Arrived…, is curated by Ruth Noack and will be presented by the Corner at the Whitman-Walker (1701 14th St. NW, Washington, DC), January 25 through March 29, 2020. It will later tour to California, Texas, and New York, through January 2021.