How Academics, Egyptologists, and Even Melania Trump Benefit From Colonialist Cosplay

From khakis to pith hats, certain items of clothing have become enduring emblems of European colonialism and particular scholars who know these problematic histories choose to engage in the aesthetics of colonialism in their everyday lives.

From khakis to pith hats, certain items of clothing have become enduring emblems of British, French, and Dutch colonialism. Should their history as sartorial symbols of empire and oppression be considered when donned today? And what about those scholars who know their problematic histories and still choose to live, to recreate, and to engage in the aesthetics of colonialism in their everyday lives?

In her new book, Melania and Me, author Stephanie Winston Wolkoff remarks on the first lady’s controversial choice of headgear when visiting Kenya in 2018: “October took Melania to Kenya, where she wore a pith helmet reminiscent of colonialists from Europe … She said her sartorial choice offended the ‘liberal media.’” According to Winston Wolkoff, Mrs. Trump went on to explain how she’d landed on the helmet to begin with: “‘I googled ‘what to wear on safari,’ saw the outfit, and liked it. So I bought it,’ she said. ‘I wasn’t making a comment on colonialism.’”

Following Trump’s visit to Kenya, her fashion choices were widely critiqued as insensitive —even though supporters claim they were born from ignorance. But what about those that dress in this garb on purpose? Among the western archaeologists working in Egypt a least a few have a particular taste for early 20th century, colonial-style attires, both in and out of the field. You thought pith helmets — one of the most easily recognizable symbols of British colonial might — and Crocodile Dundee-esque outfits were a thing of the pre-Nasser past? Well, you’re wrong. Not only are such outfits still deemed unproblematic by many current archaeologists, but some of them also willingly advertise their “vintage” tastes on social media.

This is the case of the “Vintage Egyptologist” also known as Dr Colleen Manassa Darnell. According to her Academia page,

Dr Manassa Darnell taught at Yale University as the Marilyn M. and William K. Simpson Assistant Professor of Egyptology (2006–2010), and Associate Professor (2010–2015). She currently teaches art history at the University of Hartford and other colleges in Connecticut and is a curatorial affiliate at the Yale Peabody Museum of Natural History.

Her work also includes a substantial volume of public-facing scholarship, which she performs under the name “Vintage Egyptologist” (VE). Over the past few years, VE has gathered an impressive following on Instagram and Youtube. The oldest picture on Dr Manassa Darnell’s Instagram account dates from January 2017. Her feed, which currently counts about 375 posts, has 153,000 followers. This is way more than all the Egyptologists we know. (By comparison, Zahi Hawass has 53,000 followers.) In February 2020, she was featured as a guest on YouTuber Rachel Maksy’s “Watching ‘The Mummy’ with an Actual Egyptologist” video. The clip has over two million views.

More recently, VE created a Youtube channel, which now counts 35,000 followers. While the instagram account appears to be Dr Manassa Darnell’s solo project, the Youtube page’s profile picture features her with her husband, Yale Egyptology Professor John Coleman Darnell, and the page’s “about” section reads: “We are Egyptologists with interests in archaeology, history, and vintage fashion”.

VE does provide high quality, accurate historical content, and the Darnells are doing so — through Instagram captions, Youtube videos, and cruise tours — very eloquently. What interests us here is that this Egyptological content is delivered using a so-called “vintage” packaging, which transports us to the realm of The Great Gatsby meets The English Patient. The numerous hashtags added to the Instagram captions include #archaeology, #history, #egyptology, #explorers, #explorersclub, and #indianajones. Less than a handful of Egyptian workers (three of whom are referred to as “our Egyptian family” in one instance) appear in the pictures. The few archaeological workers who do appear (in subaltern roles) are named. Apart from a couple of early 20th-century hotels (whose presence seems to be warranted because they are remnants of a “glamorous past”), no modern Egyptian settlement is represented.

In a 2018 interview with Egypt Today, Dr Manassa Darnell explained that her “love for vintage fashion and the ‘20s began when she realized how liberating the era was for women”:

As the First World War raged across Europe, women found themselves filling the roles of men. They began working, playing sports, taking part in excavations and finally they were given their right to vote. Jazz music came out of the shadows of New Orleans and started to become popular all around the world, and Hollywood’s influence on the public was at its starting point. The Prohibition had forced communities into underground clubs as nightlife and crime were embraced by all classes. Everyone was dancing the Charleston, while the prevailing flapper lifestyle became the new cool with its own slang.

The “liberated women” Dr Manassa Darnell has in mind are European, American, and white of a particular socio-economic background. Elsewhere, she claims that it makes her feel “powerful to be able to channel the past”. She then goes on to describe her approach to wearing vintage clothing in archaeological contexts:

Onsite during an excavation, I wear practical and more recent vintage, such as 1970s and 1980s khaki skirts, sometimes paired with a ‘40s or ‘50s jacket. For visits to tombs and temples, I often wear flapper dresses or jodhpur pants with boots. I hope that by combining Egyptology and vintage fashion — from a time when Egyptology and Egyptian designs, both ancient and modern, were popular throughout the world — I can encourage more people to be interested in all things Egyptian, and to travel to Egypt. By wearing the clothing of the early modern period and attempting to understand how it feels to wear and work in the clothes of 100 or so years ago, I also gain some feeling for understanding the different clothing and the lives of the ancient Egyptians.

Behind closed doors, many Egyptologists have been making fun of VE on the ground that its branding is narcissistic and ridiculously colonial. Yet public critiques by fellow academics, including Egyptologists, remain few, and those who have spoken up have generally been met with dismissive arguments from inside the field. Many academics suggest that what matters is the content, not the container; so criticism of this type amounts to nothing more than uncollegial gossiping.

We beg to differ. To us, Egyptologists and scholars in antiquity-related fields, the “vintage” part of VE is as meaningful as the “Egyptologist” part. Indeed, the highly curated, and professional, pictures and videos produced by VE are the result of conscientious, deliberate choices. These testify to a vision of Egyptology that is intimately tied to the reproduction of colonial imageries. In most cases the (white, American) body of Dr Manassa Darnell, who features at times with her (white, American) husband, is shown in Egypt, either in a monument, on a site, or aboard a “vintage” cruise boat.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BbchPGpBUNC/https://www.instagram.com/p/Bev2PVHBkF3/

The “Darnells,” as the couple also call themselves, have also led “vintage cruises” aboard the SS Sudan steamboat. The tour is organized by the travel company Goodspeed & Bach inc. A 2020 advertising pamphlet describes the boat in those terms:

Built in the 1910’s, she is the last authentic Belle Epoque paddle steamer in Africa. Her broad teak decks, brassware, and wood paneling are the stuff of romantic stories. The gangways exude a sweet aroma of beeswax; the woven rattan furniture on the deck provides the perfect place to daydream as you sip tea and watch the desert palms glide past.

An Instagram post commemorating the gala night of their 2018 tour at the Grand Cataract Hotel in Aswan gives us an idea of their audience. In addition to the Darnells, all the vintage dressed people featuring in the photographs are white.

Shortly after the cruise tour was over, the couple shot a video of themselves, dressed in jodhpur pants and Pith helmets, dancing in the Grand Tea Room at the Winter Palace Hotel in Luxor.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BjNsaiTBZm2/

As we observed above, apart from its Pharaonic ruins, landscapes and, on rare occasions, galabeya-dressed men pictured in subaltern roles, today’s Egypt is conspicuously absent. The focus is more particularly on the fashion in vogue in the 1920s. In a clip posted on Facebook, Dr Manassa Darnell explains her particular love for clothing of that period: “There’s just something special about putting on clothing that’s rooted in a particular time and, often, place.”

What, then, was that particular time like in the “particular” places the Darnells work and live in?

In the 1920s, Egypt was ruled by the British. During that time, there was an acceleration of European archaeological missions in the country, and also a rise of international (essentially European and North American) tourism. (See for instance Malcolm Reid’s Whose Pharaohs? and Contesting Antiquity in Egypt as well as Rachel Mairs’s and Maya Muratov’s Archaeologists, Tourists, Interpreters). More generally, as Timothy Mitchell and Jennifer Derr have shown, the period of British rule over Egypt, which VE celebrates as the “Golden Age” of fashion, Egyptology, and travel, was also a period of pervasive colonial violence. Back in the USA, the aftermaths of WWI had led to the “Great Migration,” and ongoing racial segregation and violence towards Black Americans fueled the “New Negro Movement’.” Unsurprisingly, VE does not engage with this type of “vintage,” but promotes instead a sugar-coated, romantic, and Orientalist image of that time period.

The elitist, whitewashed version of vintage living promoted by VE appears to be an all-encompassing passion for the Darnells. This notably shows in their September 4 “Egyptomania House Tour” video, which offers a tour of their “Greek revival” home.

To be clear, we don’t think that “vintage” fashion is an issue per se. In many ways, “vintage” objects and sartorial items can become creative, ecologically responsible ways to express oneself. And yes, vintage fashion is beautiful. Yet what happens when 1920s (European-inspired) hairdos, clothes, and accessories are purposefully featured on a white body in a way that celebrates colonial-era archaeology and travel? And what does it mean for two white, affluent American scholars to continue to produce such content now, in the age of Trump, Black Lives Matter, and Indigenous fights for decolonization? We argue that VE is very successful because it occludes: the colonial violence that, under British rule, made possible the ideas of Egypt and Egyptology they are celebrating; the complexity, multifaceted identity, and shifting nature of Egypt’s land, peoples, and histories; and many (Egyptian, American) pasts, and presents. By doing so, it stages and celebrates a white-supremacist type of vintage Egyptology.

Take this passage from the 2020 Vintage Cruise pamphlet, which concerns “Day 14: Kom Ombo and Aswan”:

This morning, SUDAN steams toward Aswan at the frontier of traditional Egypt, where ancient Nubia begins. The mighty desert slowly replaces cultivated land as we proceed up the Nile. It is easy to see that this is where pharaonic civilization once ended. The lands above the great cataracts nourished the Nile Valley with mineral-rich silt during the floods. Nubia also provided Egypt with gold, precious woods and ivory, as well as soldiers for its military machine.” (our italics)

To whoever is acquainted with the deep, entangled histories of Egypt and Nubia — and this includes the audiences of the recent virtual talks by Stuart Tyson Smith and Solange Ashby — the simplistic, racially charged, and anti-Black subtext of this passage is striking.

For Dr Manassa Darnell and her husband, vintage living serves as a portal through which they — equipped with the intellectual capital brought about by their association with Yale University — can disseminate knowledge about Pharaonic Egypt to wider, non-academic audiences. What does the success of this strategy mean, about the broader reception of ancient Egypt, about Egyptology’s ongoing colonial entanglements, and about the relationship of most of the members of our fields with public-facing scholarship?

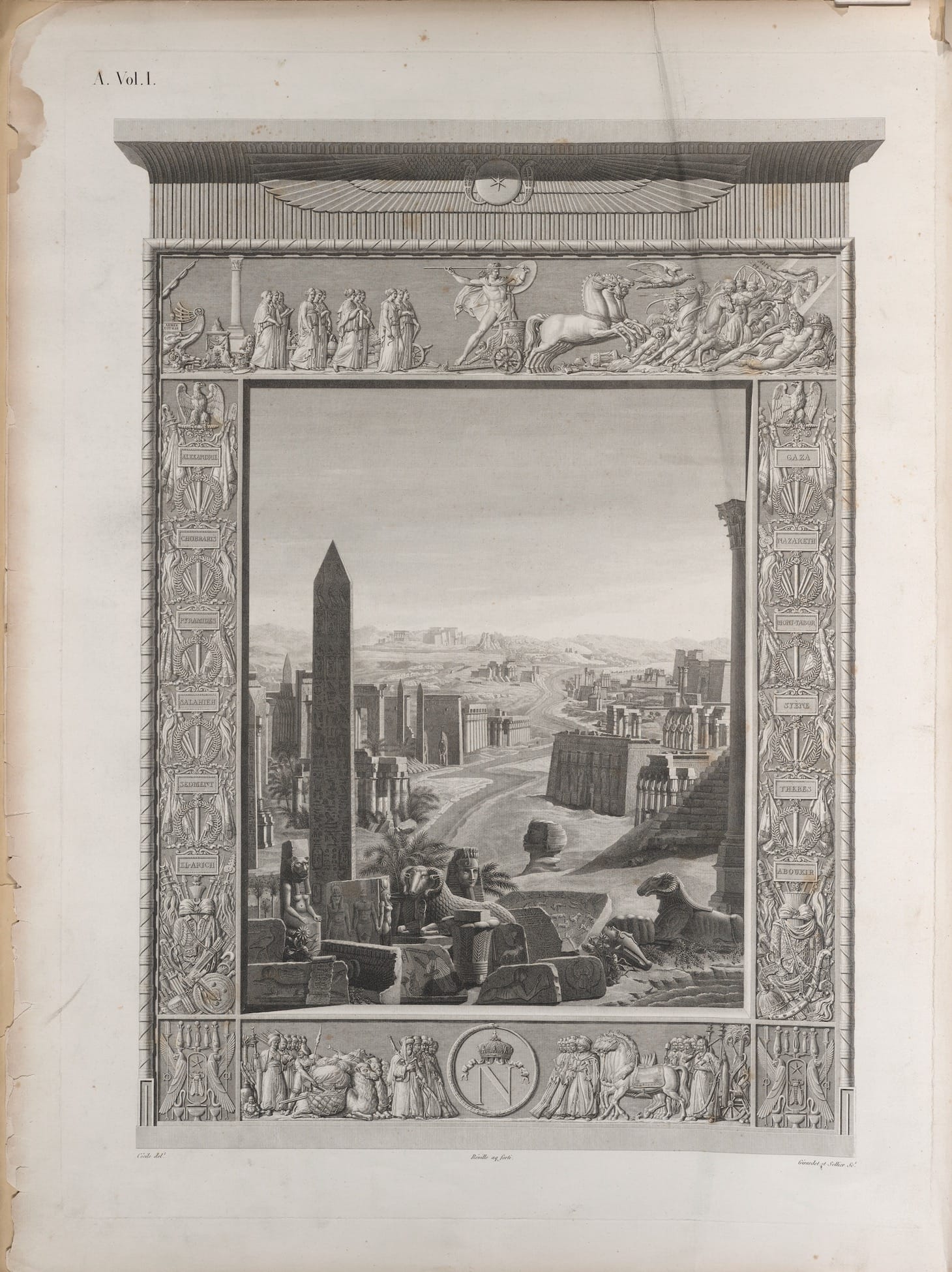

VE’s curatorial anchoring resides in the realm of the Orientalist fantasy, far, far away from anything written since Edward Said, and in disjunction with the historical experience and sensibilities of most inhabitants of modern and contemporary Egypt. The “Egypt” it portrays is reminiscent of the frontispiece of the 19th century French multivolume series Description de l’Égypte published after Napoleon’s conquest. This fictive, deserted landscape was cut through by the Nile river and dotted with impressive pharaonic monuments covered in hieroglyphics, ready to be “explored” by white “experts,” whose lavish and civilized lifestyle matches the long-gone sophistication of ancient Egypt’s mystical grandeur. In this regard, the Classical-style frieze (which shows an Apollo-looking, Muses-leading Napoléon driving the Mamluks out) surrounding the Description’s frontispiece’s rendition of Egypt serves as a powerful statement of the power relationship at stake: Egypt is defined by and for the male, European conqueror’s ability to penetrate, occupy, and, to paraphrase a now famous political slogan, “make her great again”.

The erasure of post-642 AD Egypt and of the Egyptians themselves from the frontispiece of the Description de l’Égypte is a stunning Freudian slip, a powerful window into the enduring (sub)conscious relationship that links a large proportion of scholars, students, and non-academic crowds to Egypt. Such a zoomed-in, myopic image of Egypt belongs to a Eurocentric fantasy that is, as the public success of VE shows, still very much alive, both within and outside of academia.

While VE’s audience seems to be mostly white and based in Europe or settler colonies, it is also important to acknowledge that the interiorization, performance, marketization, and consumption of colonial aesthetics is a more global phenomenon that is often introjected by colonial subjects. The recent petition for the return of a French mandate over Lebanon offers a striking example of how the civilizational discourses that accompanied European colonial rules remain alive in “postcolonial” countries.

It should not come as a surprise, then, that VE counts many Egyptians amongst its followers. The recent feature in Egypt Today quoted above attests to this phenomenon. We also ought to mention another, more artful example: For years, Egyptian Egyptologist Zahi Hawass has been carefully subverting a colonial-inspired dress code to foreign and local audiences. His appropriation of Indiana Jones’s looks offers a compelling example of a colonizer’s outfit being recuperated by a member of a historically colonized community for self-assertive purposes. More broadly, social media publications celebrating the “European fashion” and ways of living of pre-1952 Egypt (and notably Alexandria) abound, and the same trend is found in association with other western Asian countries: from Iran to Afghanistan to Syria and Iraq. For many locals and members of diasporic communities, such cultivated nostalgia for a lost “cosmopolitan” past is often rooted in personal experiences of loss, socio-economic hardship, suffering, and exile. Yet this romanticization of “lost golden ages” can also be, concomitantly or not, layered with (un)conscious subtexts that testify to modes of internalized coloniality.

https://www.instagram.com/p/BQhMHYbhdV6/

It is too easy to mock the examples provided so far without questioning the mechanisms that allowed such public personae to fully manifest themselves in the first place. The large, expanding following of VE testifies to the ongoing popularity of and nostalgia for colonial imageries among large segments of western (especially North American) populations. As such, and whether it wants it or not, VE is eminently political. Indeed, the project is not disconnected from more open forms of apology of colonialism and imperialism, and this is where the problem lies. The public success of VE shows how the image of Egyptology remains largely Orientalist. While scholars are very prone to laugh at the many clichés and stereotypes that shape the way ancient civilizations are portrayed in mass media, we should not forget that these very stereotypes have been, for most of us, the starting point, the spark that ignited our passions, fueled our initial interest for Antiquity. They are also an important gateway to private funding, something which many archaeologists, including the Darnells, understand perfectly.

The past years have seen an increase in the use of ancient history by ideologically minded individuals and groups. One can think of the selective and tendentious recuperation of Greek and Roman imagery by extreme conservative, white supremacist groups; of the apology for western-style looting (including the defense of the British right to own the Elgin Marbles); of the Museum of the Bible debacle. In this context, it is as irresponsible from scholars working on the ancient world to deflect the question of the “decolonization” of the field by appealing to a white-washed, elitist nostalgia for the “good old days” as it is to contemptuously ridicule or ignore the proponents of such tropes. In the era of a resurgence of white supremacy and neo-fascism, and the onset of COVID-19, in an age, in other words, where the humanities are at the most relevant yet most threatening crossroad they’ve faced in decades, we, intersectionally minded antiquity scholars, cannot afford to look the other way anymore. It is time for us to occupy the arena of public discourse equipped with our scholarly insights more creatively and more loudly.