Thomas Carlyle, a Chronically Constipated Racist

Hidden in the bowels of the London Library, a 19th-century pamphlet contains its founder’s most bigoted views.

LONDON — “It’s too long by far!” I’m telling my barber. It’s a chilly late Monday morning, and I’m down at Q for Hair at Clapham North for the weekly beard trim. I’m pulling at it as I sink into the chair. We’re exchanging glances through the mirror. “I don’t want to look like old Carlyle now, do I?”

“Who’s he then?” my barber says, silver beard trimmer frozen at breast height. Here’s what I tell him, pretty well.

They once called Thomas Carlyle a “Victorian Sage.” He towered over the Age of Queen Victoria like a colossus, his books best-sellers, a mighty influencer indeed. He first roared into view with a brisk, noisy, multi-volume history of the French Revolution, followed that up with a biographical study (also in several volumes) of Frederick the Great of Prussia, and then went on to write much else that left his audiences cowed and awe-struck.

His fiery prose was thunderously orotund, his sentences long and convoluted, his manner of address stuffed full of wind and indignation. He never used 10 words when 100 might serve just as well. He was several things in one: moralist, historian, social critic, soapbox orator. His sentences bristled with exclamation marks!

He also helped to bring into being two of London’s greatest cultural institutions: the National Portrait Gallery and the London Library, a lending library unlike any other.

I went in pursuit of Carlyle the other day. My first call was at the National Portrait Gallery just north of Trafalgar Square, which had a makeover a few months ago.

But why was I going after Carlyle anyway? Because his reputation has taken a great nose-dive. He was once a great bang of a man. Now he’s a whimper. Why? Racism.

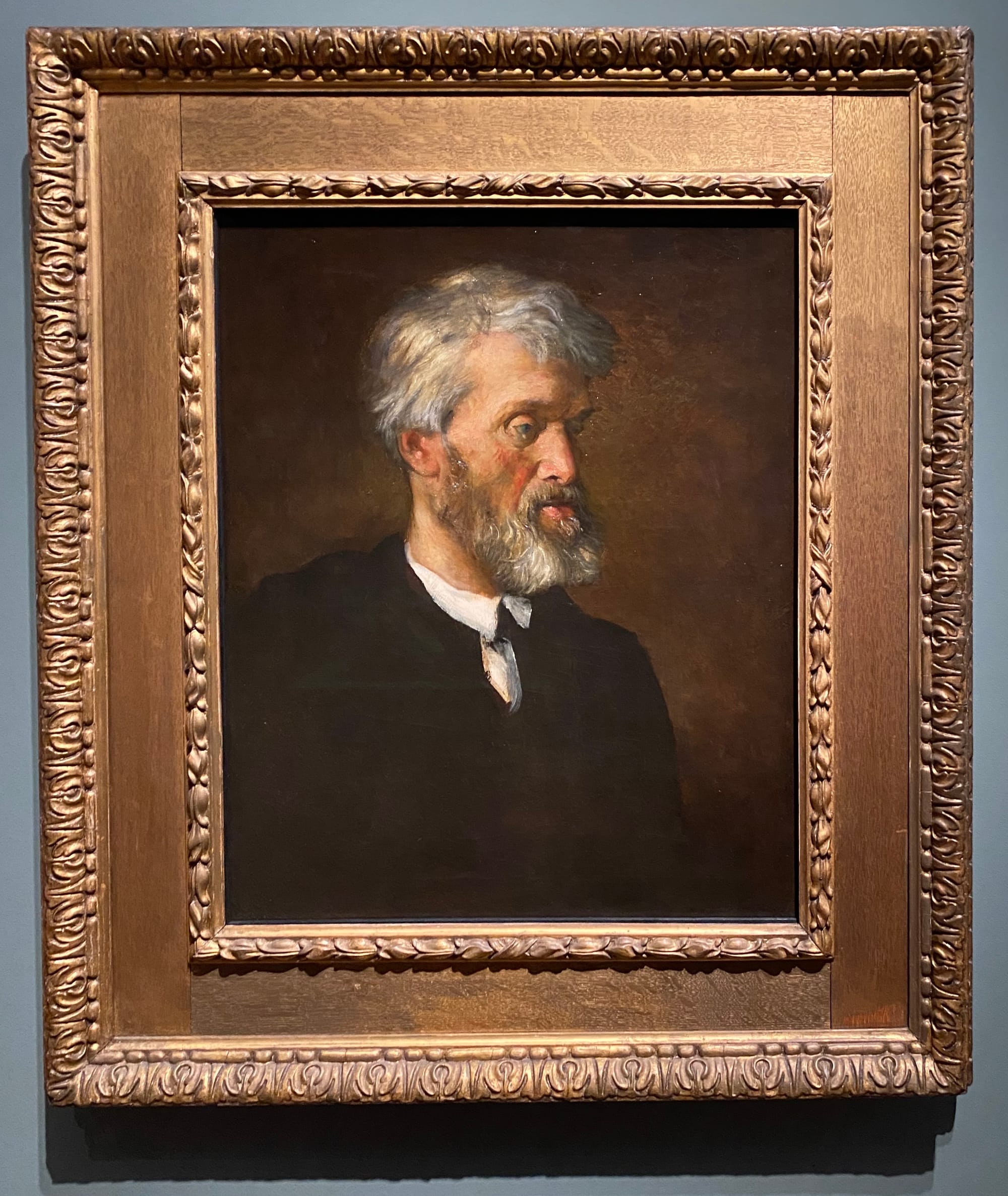

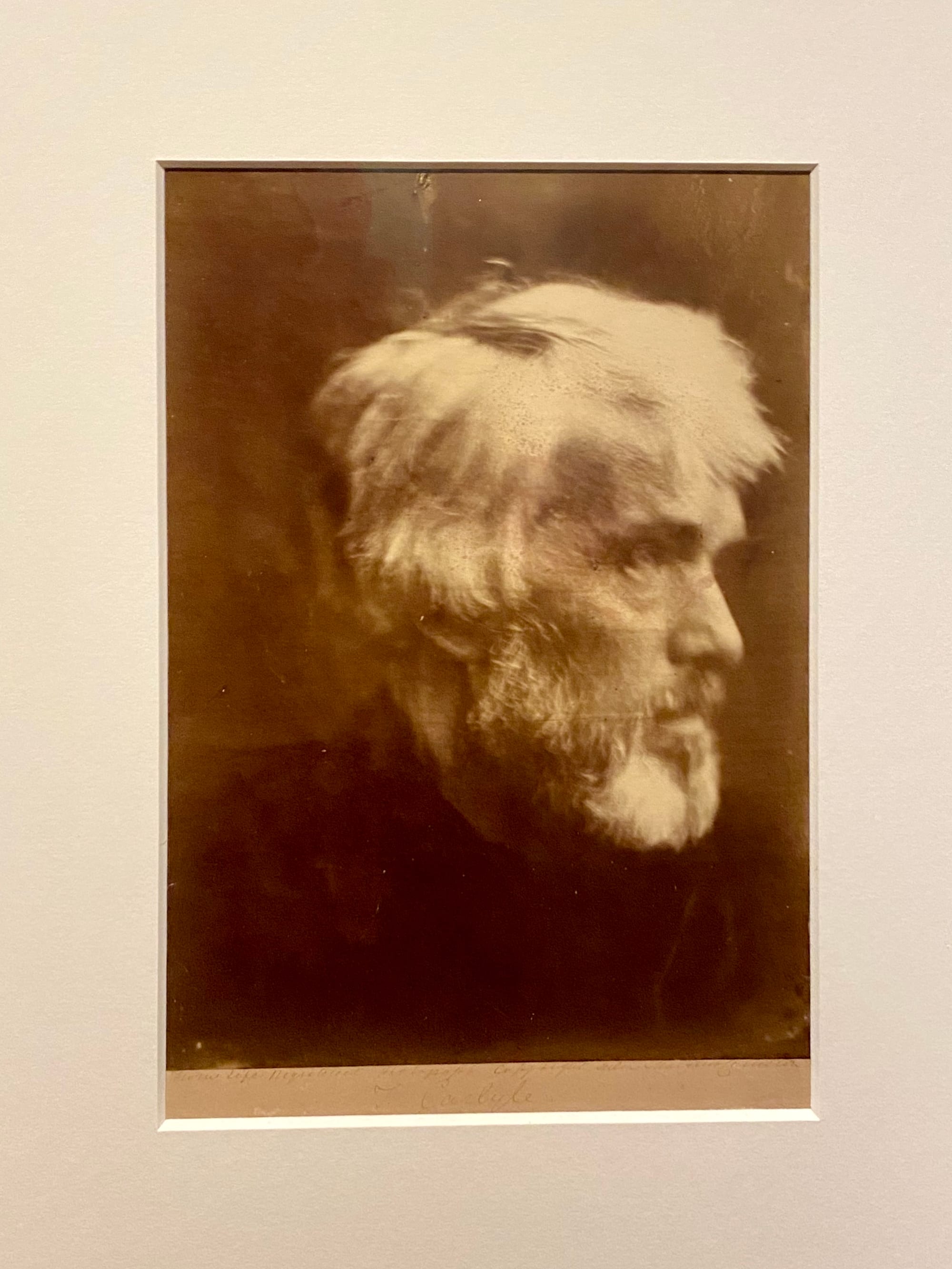

There are two portraits of the man in the Portrait Gallery, one that has appeared since the makeover, the other a photograph by Julia Margaret Cameron, taken in 1867, when Carlyle was 72. The 1868 painting is by George Frederic Watts, and Carlyle hated it. The sittings were acrimonious, and Carlyle later commented that the portrait was “the most insufferable that has yet been made of me [...] a delirious looking mountebank full of violence, awkwardness, atrocity, and stupidity.” (He was often testy.) His hair and beard in Cameron’s photograph, characteristically blurry, makes his defiant profile look like a great haystack in the floods. He didn’t like that one either. “Has something of likeness,” he grudgingly conceded, “though ugly and woe-begone.”

I was thinking of that image when I mentioned his name to my barber. Beneath the portrait by Watts, the gallery mentions the charge of racism without going into any specifics. It also tells us that he was a great supporter of the creation of the gallery itself because he thought that the nation should enjoy the privilege of coming face-to-face with its heroes. He was doubtless thinking that he himself would be amongst that august company.

The London Library, neatly tucked into the top right-hand corner of St James’s Square, was Carlyle’s creature. The website still reminds us that he was its founder. London — unlike Liverpool, Manchester, and Norwich — had no such institution before he brought this great private lending library into being. Why did he do it though? In part, because he could not bear to sit amongst the books of the old reading room of the British Museum, surrounded by its despicable gang of “snorers, snufflers, wheezers and spitters.”

I have been a member of the London Library for decades, and I returned there the other day to try to put some flesh on the bones of these so-far unspecific charges against the person and the reputation of Thomas Carlyle. I have witnessed his gradual disappearance over the years. Was there not once a portrait of him on display at the foot of the great, red-carpeted staircase which sweeps you up, soundlessly, to the open stacks on the floors above? Do I not myself still own a bookmark that shows an image of the marble, neo-classical bust of the man that was once on display here? Is that bust still in residence? Or is it that I have not looked carefully enough?

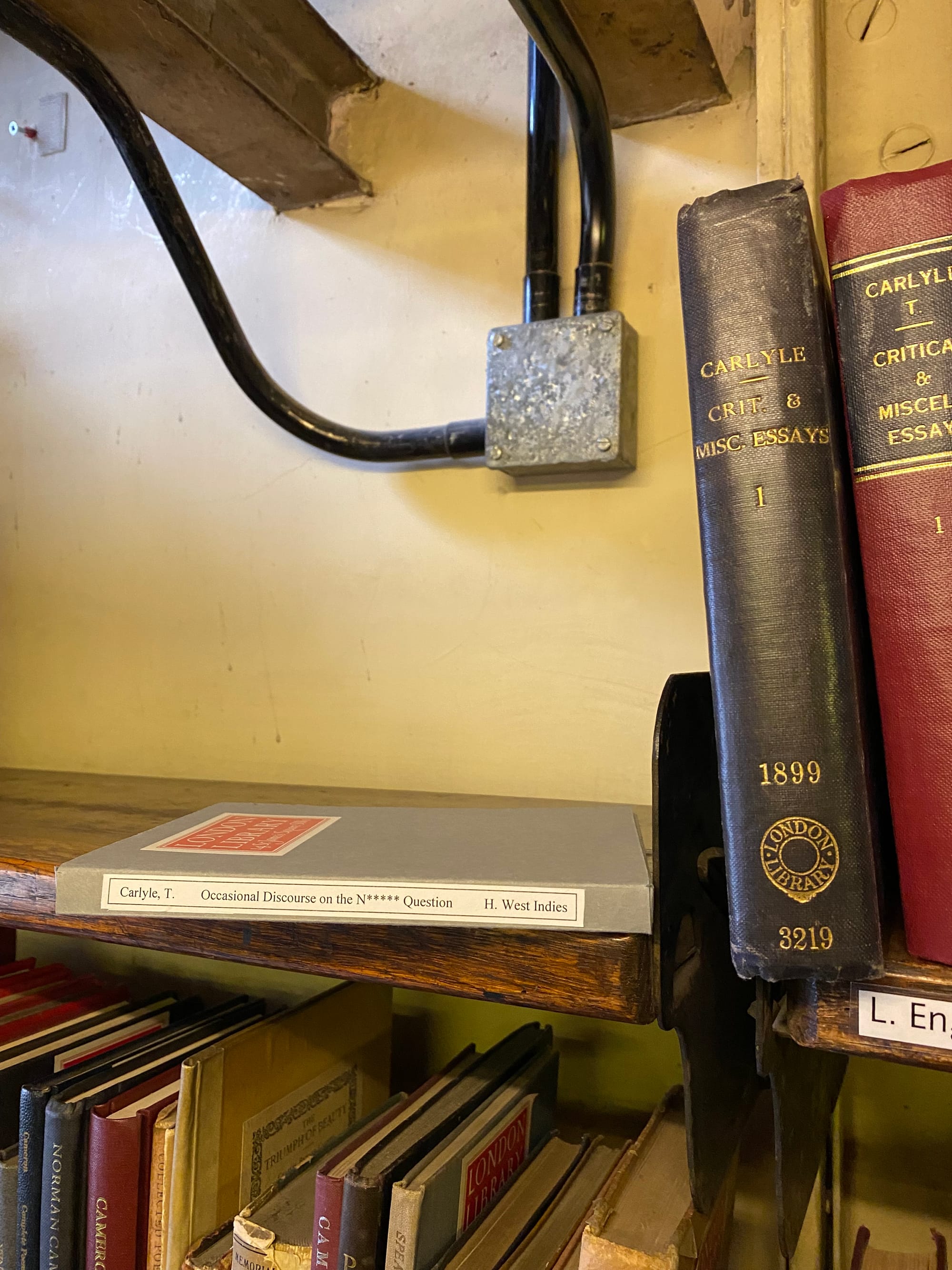

I present myself to the young librarian at the long desk on the ground floor. I tell her that I am looking for a particular publication by Carlyle which is said to have been published in 1853. Its title? Occasional Discourse on the N***** Question.

I myself own an incomplete Victorian edition of the collected works of Carlyle, and, try as I might, I have found no reference to any such publication. No index seems to mention it. Was it left out of his collected works? Hence my inquiry at the desk. She stares at her screen for long on long. Puzzlement declines to a frown.

“Why don’t I go and examine the volumes on the open stacks?” She gives me a kindly, mildly apologetic smile, and I walk away and mount the noiseless stairs in the general direction of "Eng.Lit," letter C.

The upper floors of this library are a strange marvel. They are of thick, perforated metal through which you can see the light bulbs, books, and the seekers after books on the floor below. Your feet clang as you walk. The spaces between the long stacks are relatively narrow, and intermittent string cords are there to be pulled on. A light goes on, often sputteringly. One hundred (or so) books by or about Mary Shelley come into view.

I am lucky. “C” for Carlyle is quite close to a window, so there is enough natural light to see them by! My general impression, as I scan the collection, is one of surprise. Once upon a time, Carlyle would have been taken very seriously indeed, as Dickens, for example, continues to be taken. But the Carlyle collection seems a bit random, if not miscellaneous. Even the sets of Victorian editions look incomplete. Has there been some offloading of Carlyle? I look through the volumes of miscellaneous essays. Nothing. I look through the single index to those volumes of miscellaneous essays, hoping to catch a reference to something.

Then my luck turns: The door to my left swings back, and the same young librarian dashes in, a mite breathless. “I have found it!” she says, handing it to me. It is very thin and small, and it is contained within a grey cardboard folder. Where did she find it? I look down at the category on its spine: “H. West Indies.” It lives amongst the books which tell the history of the West Indies.

The pamphlet was published by Thomas Bosworth of 215 Regent Street in 1853, having first been printed in the December 1849 issue of Fraser’s Magazine. This paperback edition that I am now holding (a facsimile reprint of that pamphlet of 1853) was published in 1992 by Cornell University Press amongst the Cornell University Library Digital Collections. It was acquired by the library on 16 October 2008, and then re-bound in stiff boards; its date stamp is 19 February 2009. The date-of-issue page at the front of the book shows that I seem to be the first member to take it out on loan, almost 15 years later, on 20 January 2024.

The book’s author is said to be “unknown,” but this is a facetious, unfunny sleight of hand on Carlyle’s part. The text is said to have come into his possession in the form of a handwritten account by an “absconded reporter” from a public meeting called Dr. Phelim M’Quirk. This gives Carlyle permission to indulge in breezy, scurrilous reportage, and always in the name of someone else. What then is wrong with the West Indian locals, according to Carlyle? "Indolence." A refusal to work, a refusal to acknowledge Anglo-Saxon domination, amidst waste and putrefaction. Carlyle saves the worst of his ignorance, his hysteria, and his vitriol for the closing pages, when he describes the Indigenous islanders as sub-human, adrift without God or a Master.

My near neighbor, once a doctor and now a self-made art critic, asks me what I am working on at the moment. We are exchanging words on his doorstep. "Carlyle," I tell him. He has just the one word to share with me about Carlyle, and he utters it with long-faced solemnity: "Constipation, Michael, constipation!"