Ai Weiwei Explores the Scale of Crisis in Four Large Installations

Four Ai Weiwei shows across Manhattan explore the aesthetics of crisis and the deluge that might consume us.

A singular talent, Ai Weiwei has always had a knack for inserting himself into the issues of the day. Easily the world’s best-known political artist, who taps the river of discontent bubbling up at any given time, Ai is now poised to unveil a massive connected series of shows spread across four of New York’s toniest galleries: Lisson Gallery, two Mary Boone spaces, and Jeffrey Deitch.

When I asked the artist about the inspiration for the shows, he replied, “It’s too many things in my mind,” indicating the expansive nature of the material that seems to sprawl — both physically and in terms of subject matter — in every direction, even if the main aspects focus on China (Mary Boone) and the refugee crisis in the Mediterranean (Deitch and Lisson). The artist says all four installations are connected, and indeed, it’s easy to see how. Using the aesthetics of abundance, Ai continues his interest in politicizing everyday objects that he encodes with new, sometimes subversive meanings.

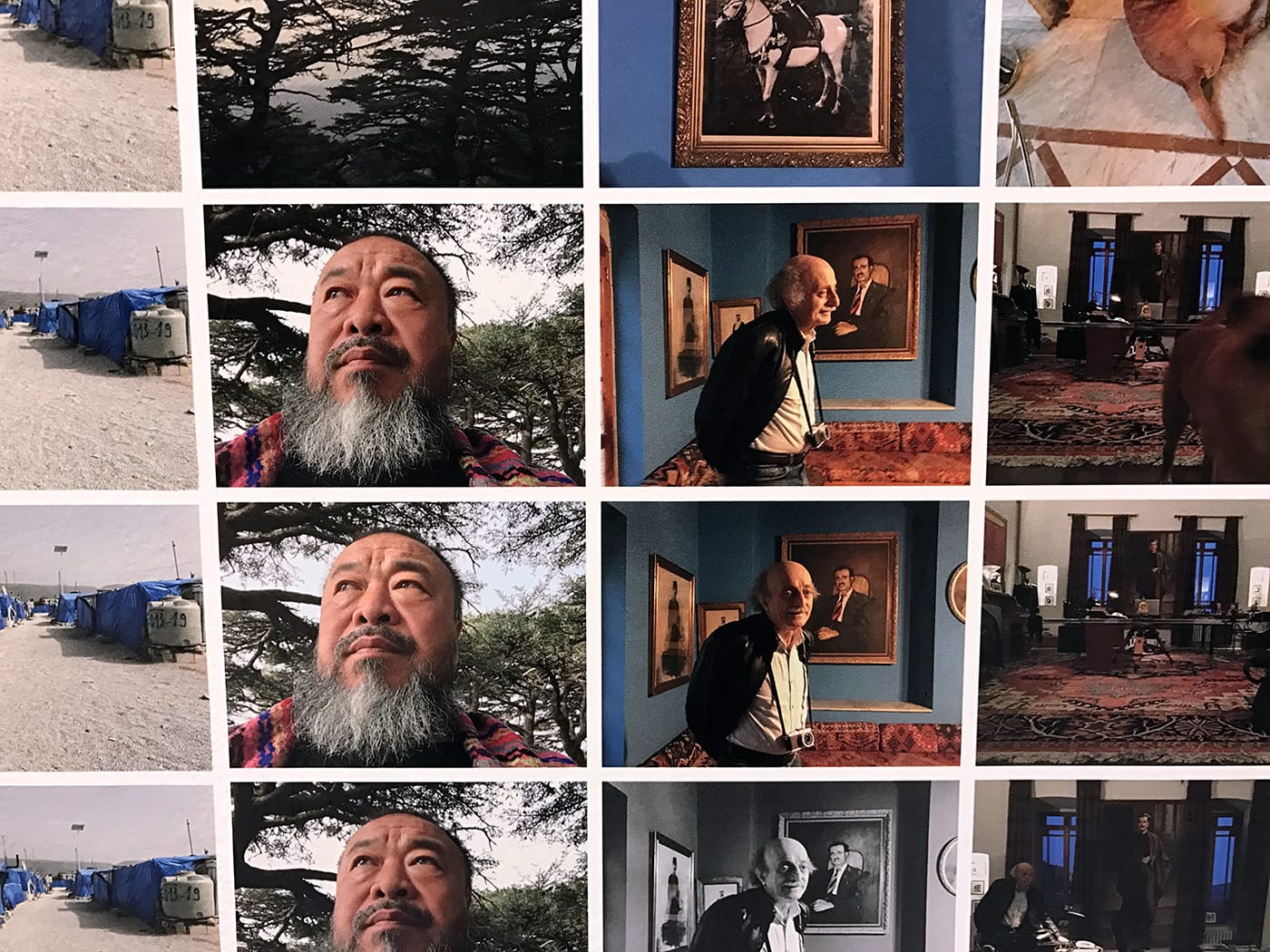

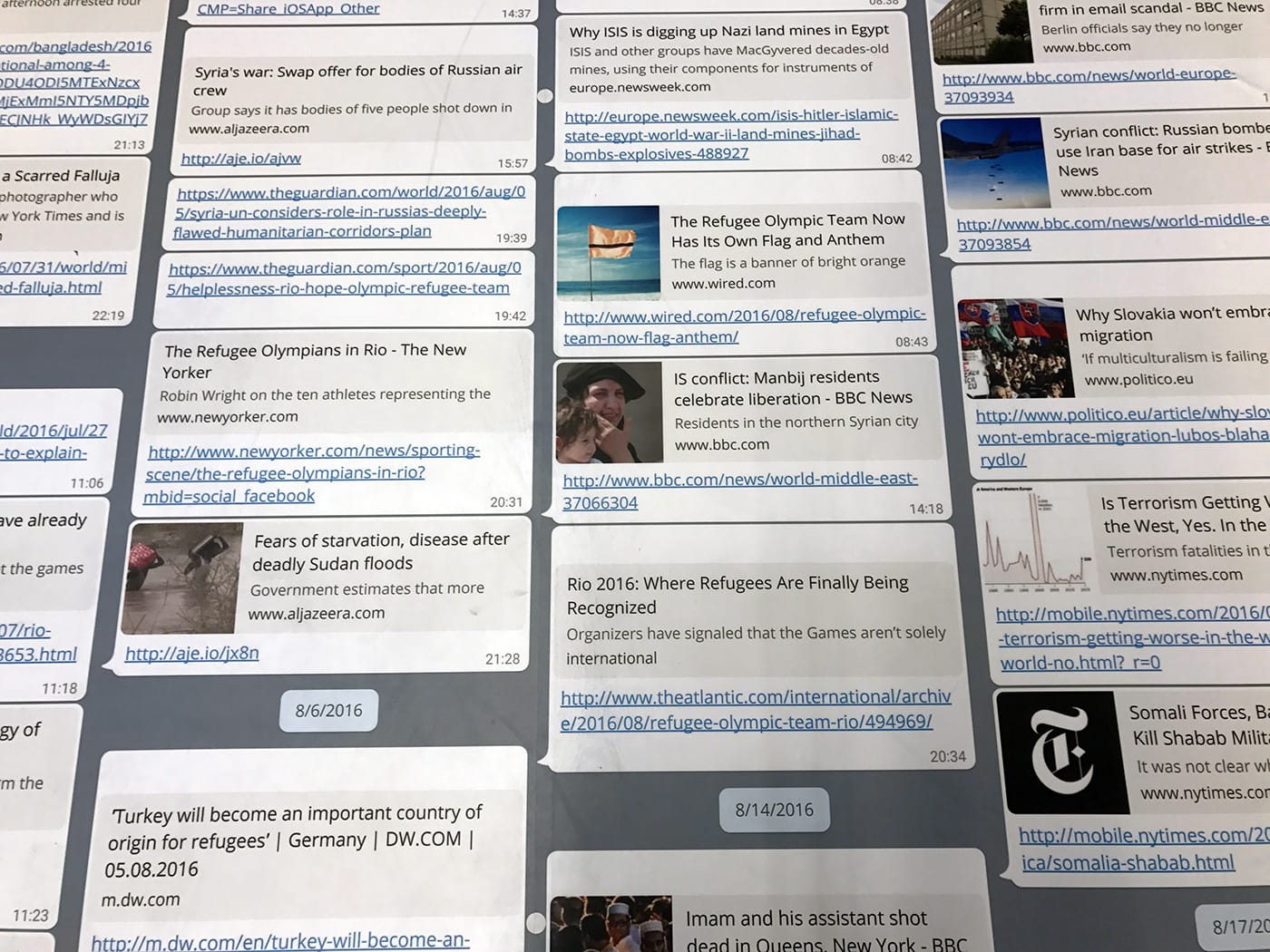

In many ways, the most emotional installation is the one at the Jeffrey Deitch space on Wooster Street. It’s filled with clothes and shoes from refugees that were carefully collected, washed, and pressed. The items — which the artist’s staff negotiated with local Greek government officials to procure — are displayed on racks and in rows, as if in some strange and trendy secondhand store. These are set against a backdrop of wallpaper covered with images from social media — many of which feature the artist with migrants — while the floor is papered with printouts of tweets of news stories about refugees, protests, and other political actions collected by his studio staff since January 2016. The impact is overwhelming and somewhat numbing, but the urgency of the work is palpable, as the accumulation of objects stands in for the masses of refugees and the flood of information that has drowned out their identities.

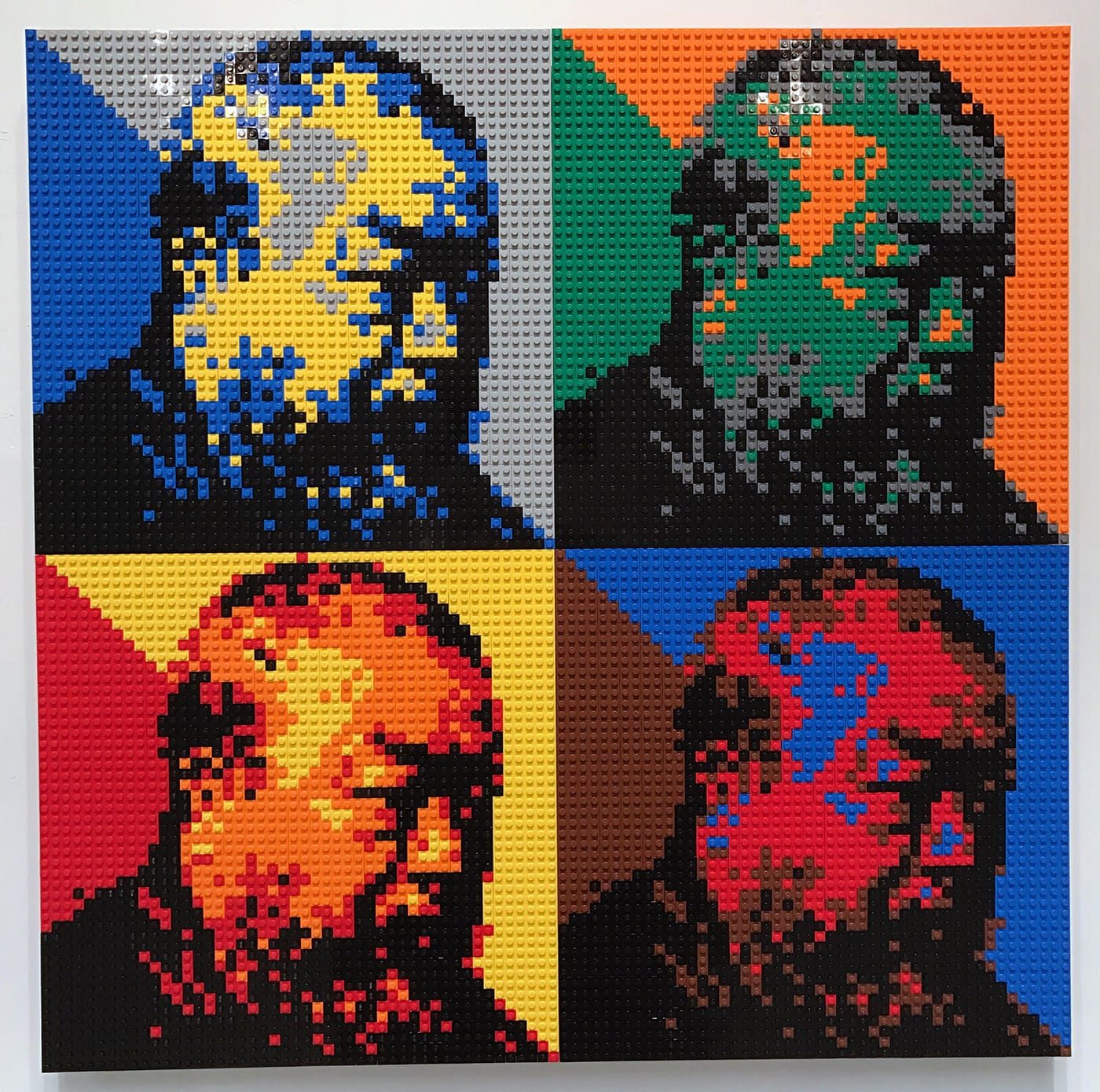

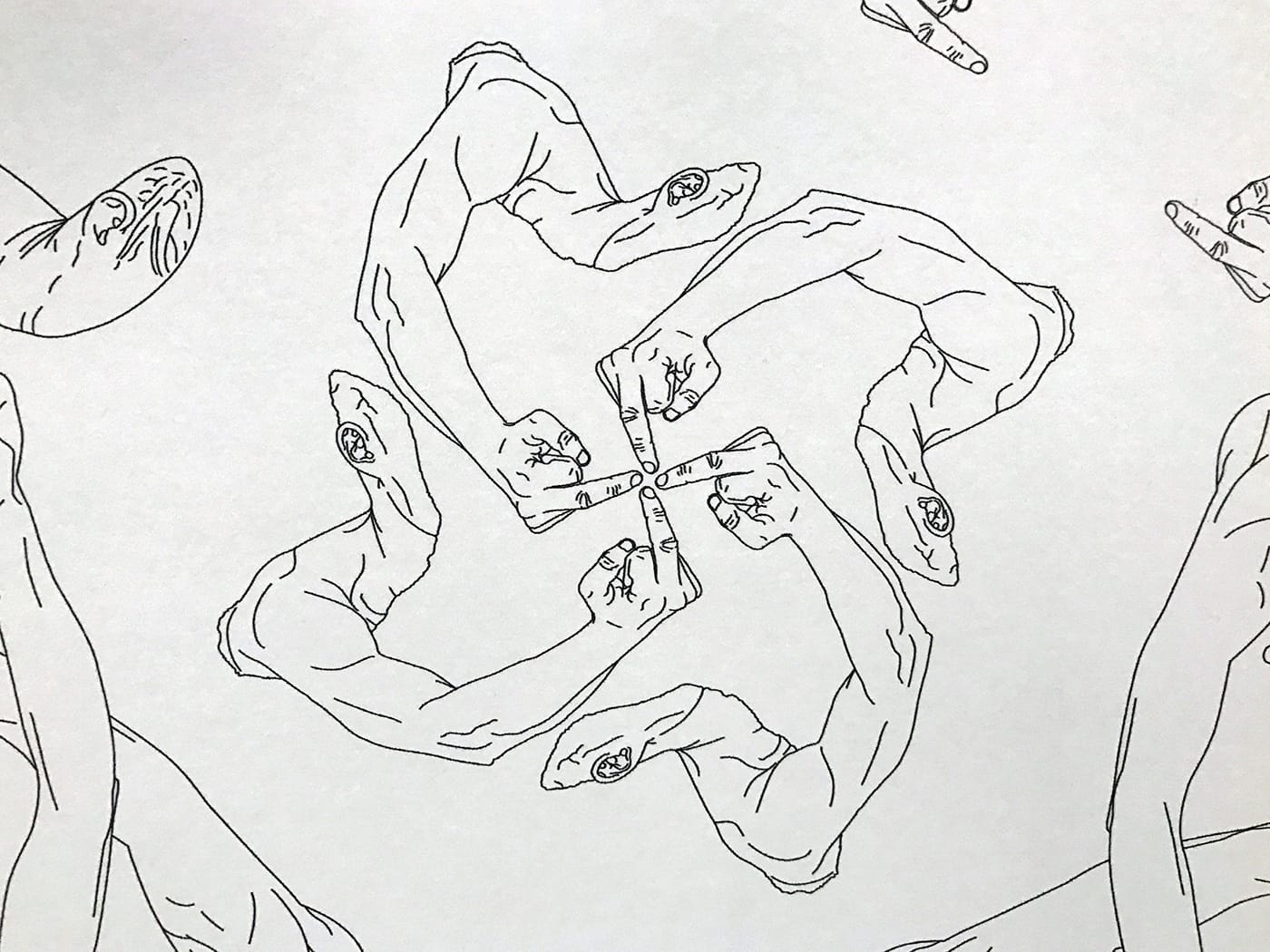

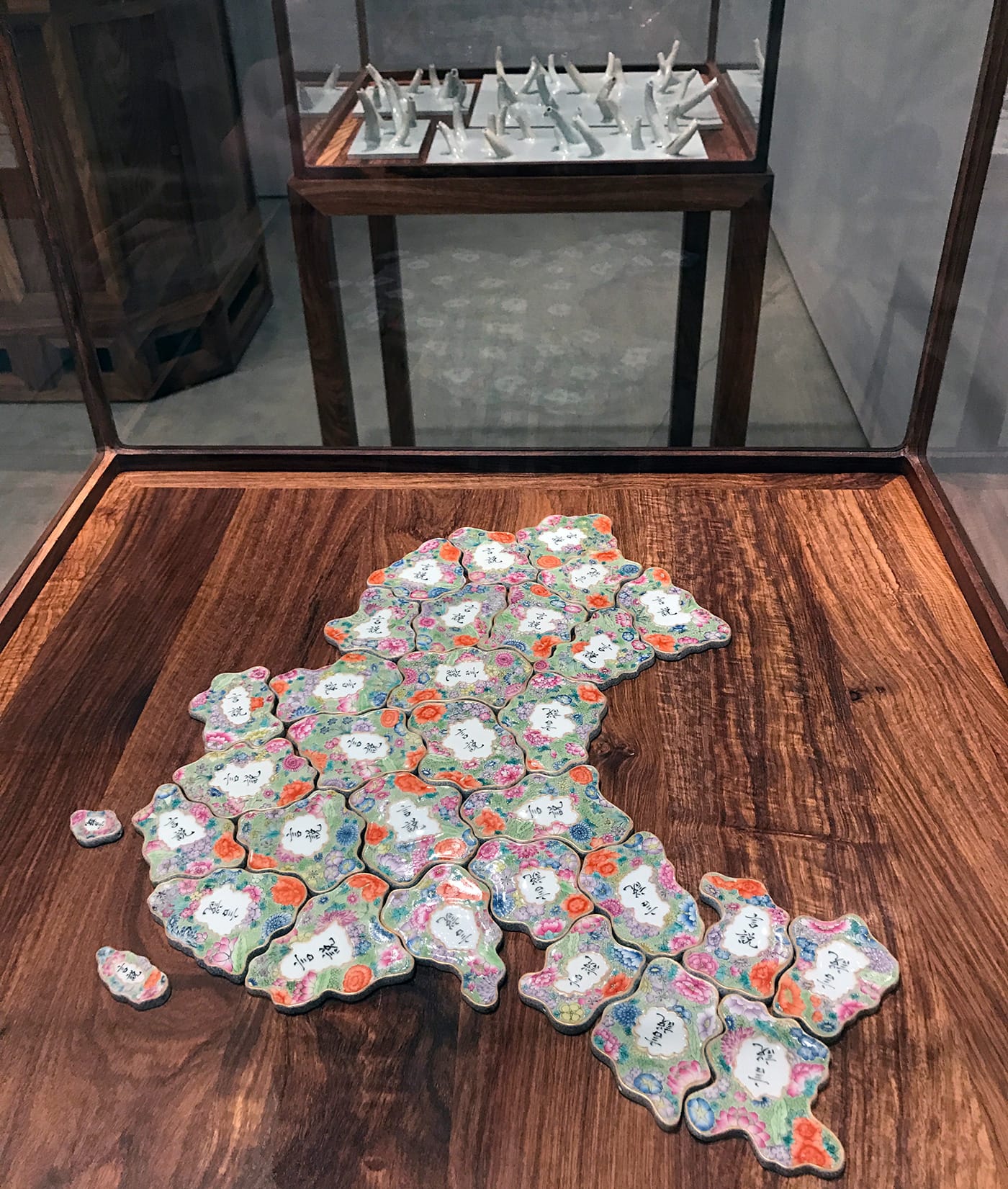

Uptown, at Mary Boone Gallery’s Fifth Avenue space, a circle of porcelain teapot spouts wraps around a central column, while patterned wallpaper depicting an arm and hand giving the finger decorates the walls all around.

The power is in the reproduction of images, in the echoing of the forms, and the meditative quality of objects that shift contexts from daily use to rarefied galleries. Many of these objects — teapot spouts, clothes, shoes — resemble discarded fragments and there is hope in the way they are cobbled together, even if that’s part of the beautiful illusion of wholeness.

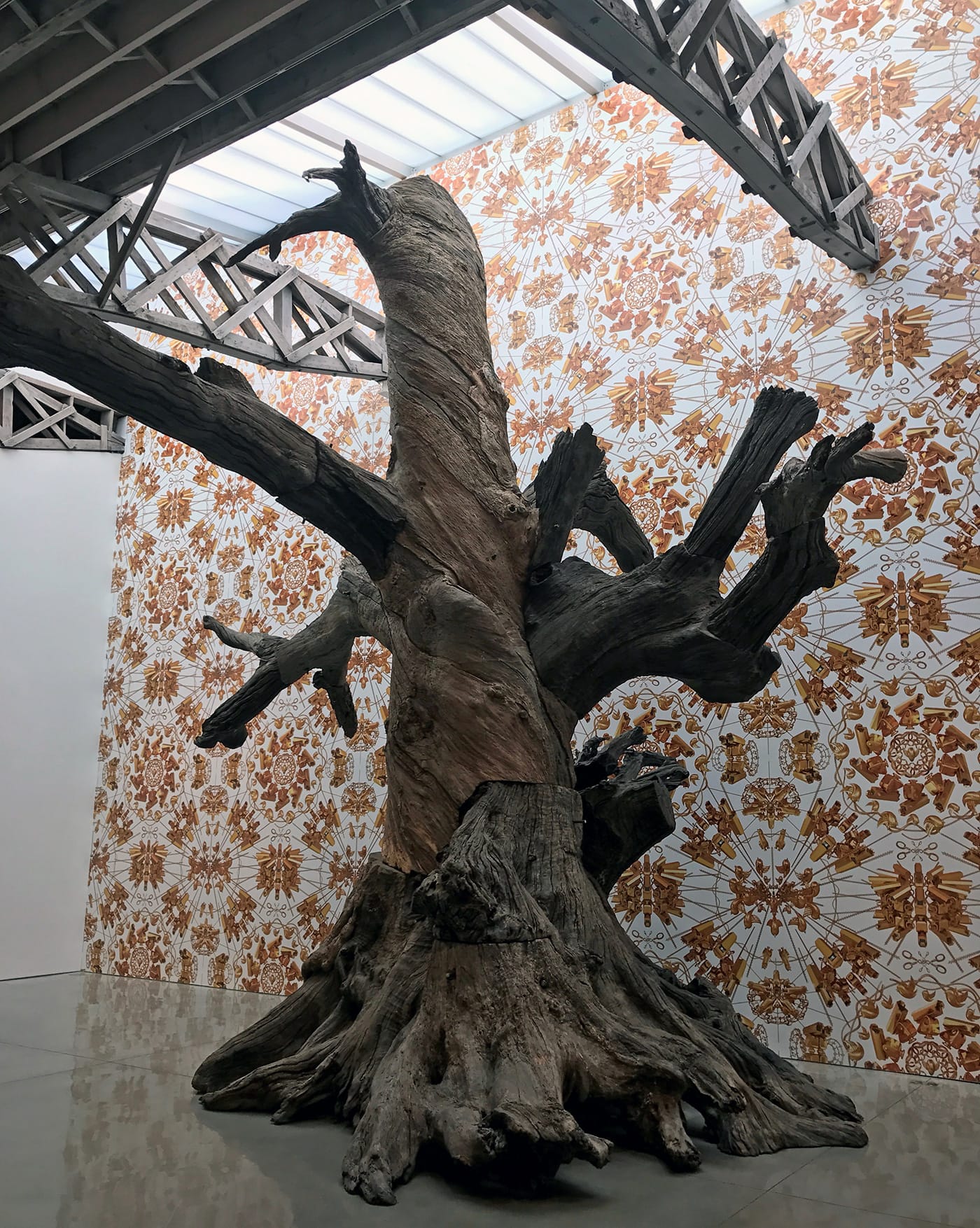

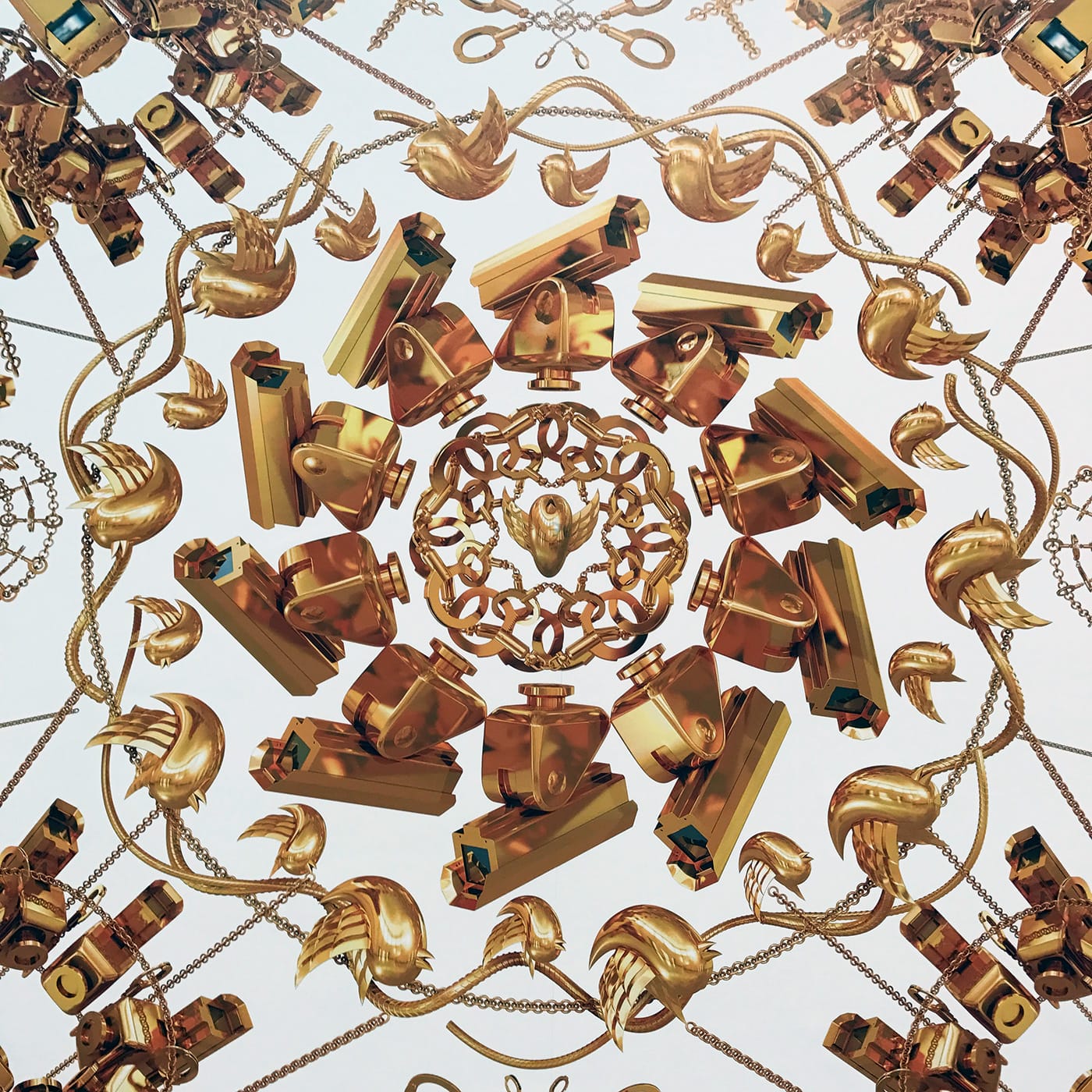

In Mary Boone’s Chelsea space, a large central tree, pieced together with what look like bolts and rods, resembles a dead carcass. It’s set against a golden wallpaper of Twitter birds and surveillance cameras. Much of the iconography here is familiar to those who follow the artist’s work, but it takes on a new sense of visual opulence, as the images spiral and radiate outward. In the shiny surface of the Twitter bird, the reflection of a gallery (not the one you’re standing in) appears like the shadows in Plato’s cave, offering us the resemblance of another place, unidentifiable but familiar.

I couldn’t help but imagine Ai’s wallpapers — all of them — papering the bathrooms and hallways of the über-wealthy, infiltrating those dens of exclusivity like Trojan horses. The forms are pristine and polished, the graphic images precise and mirrored, and they are all bathed in the illusion of newness that makes them particularly attractive for consumption.

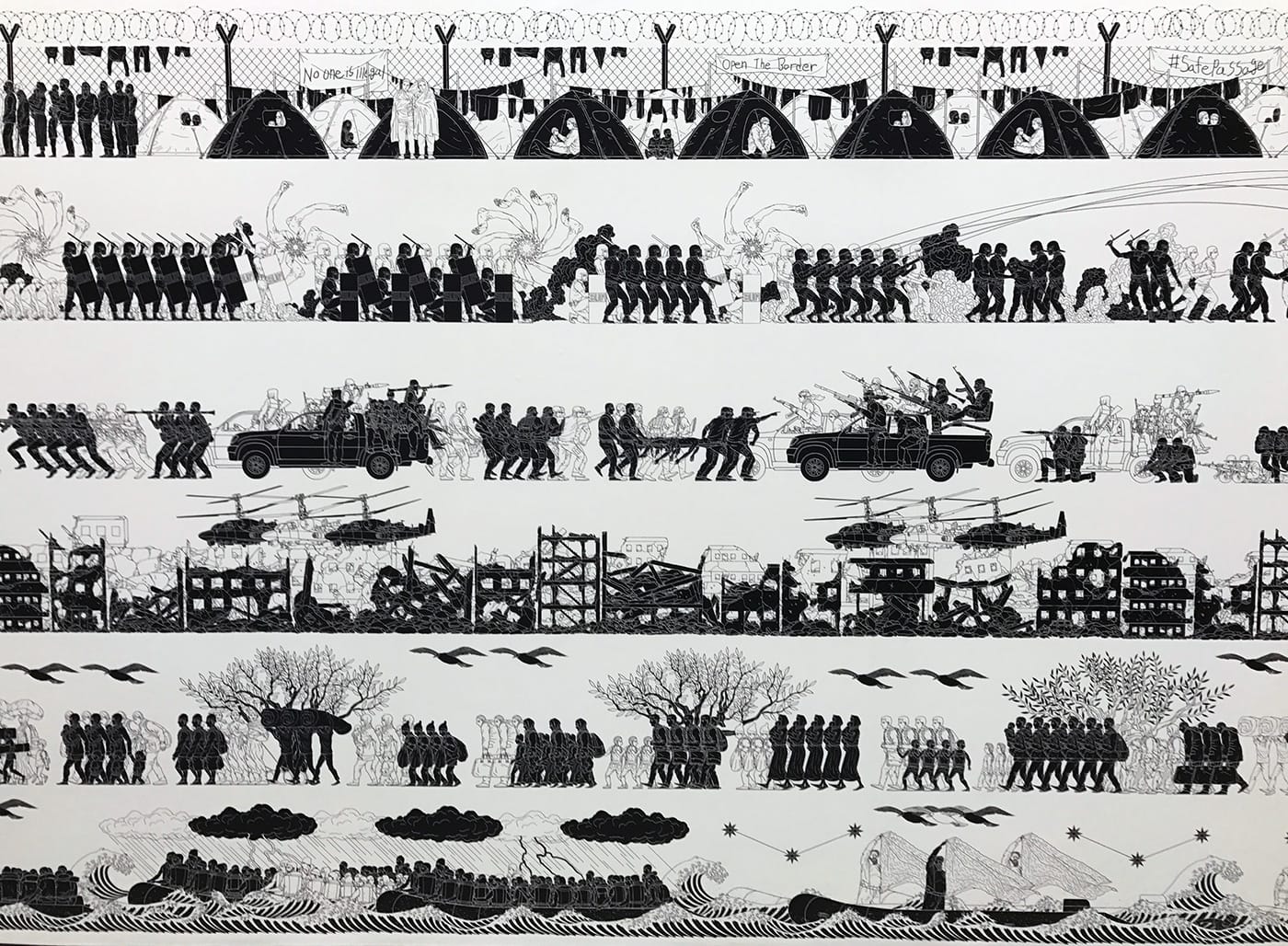

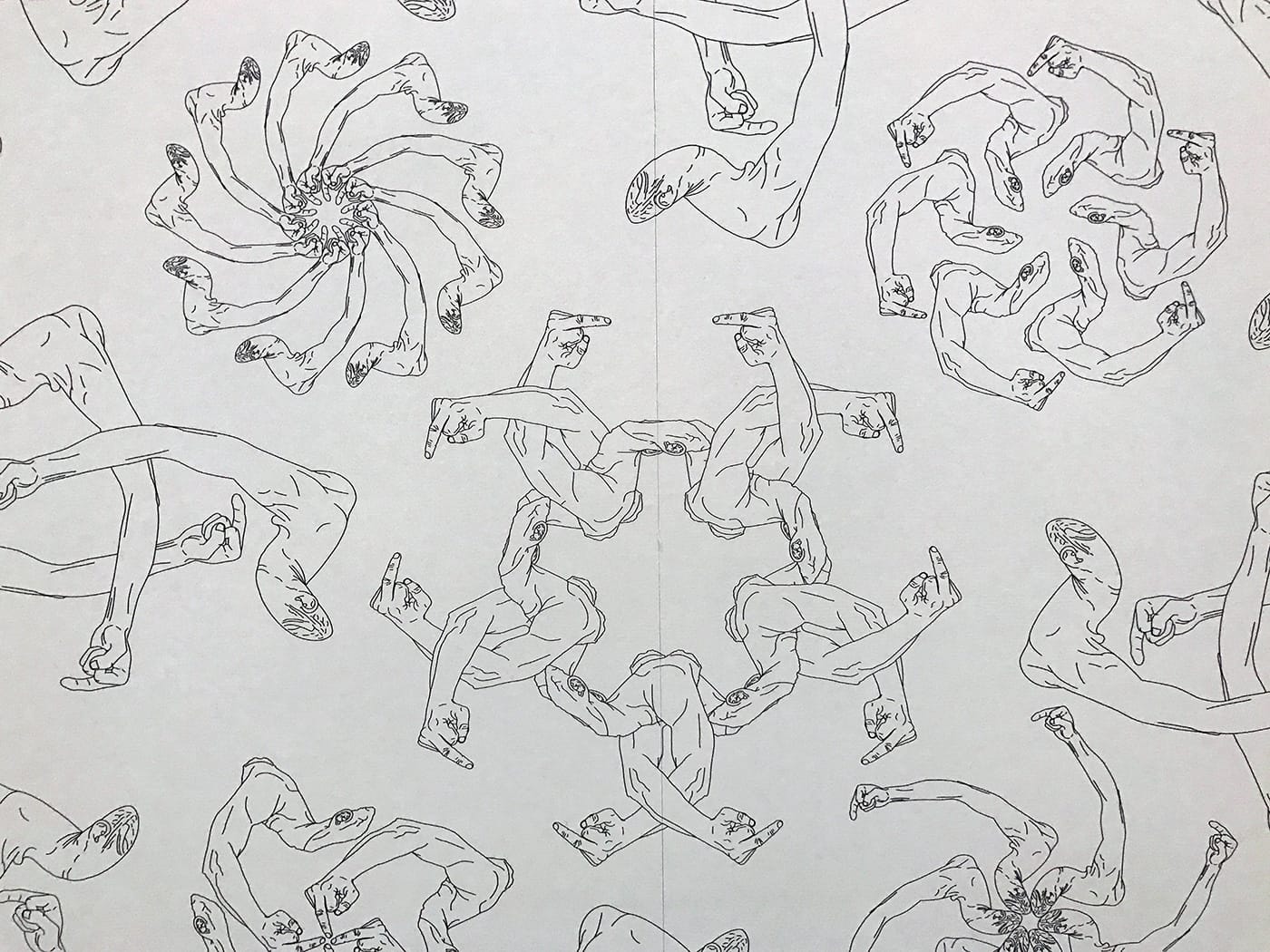

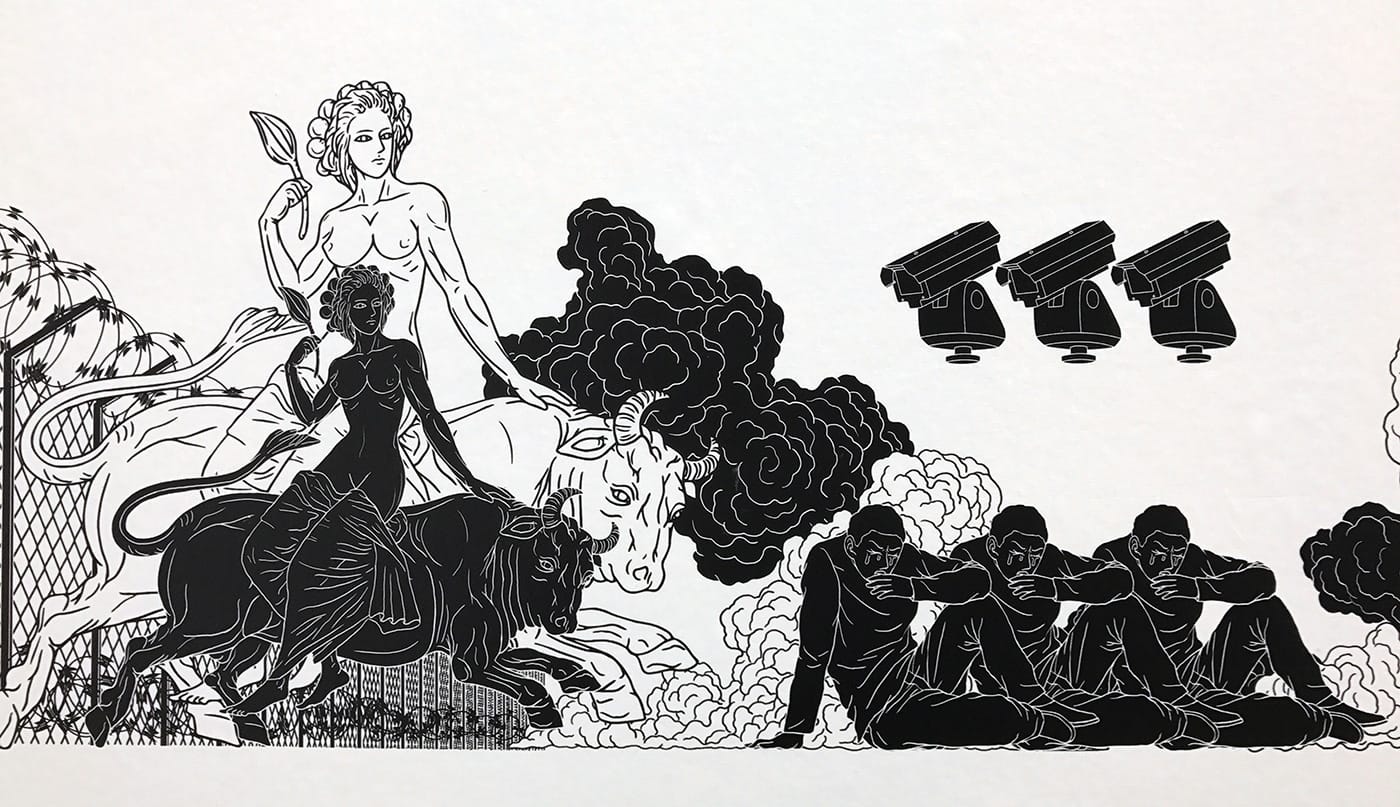

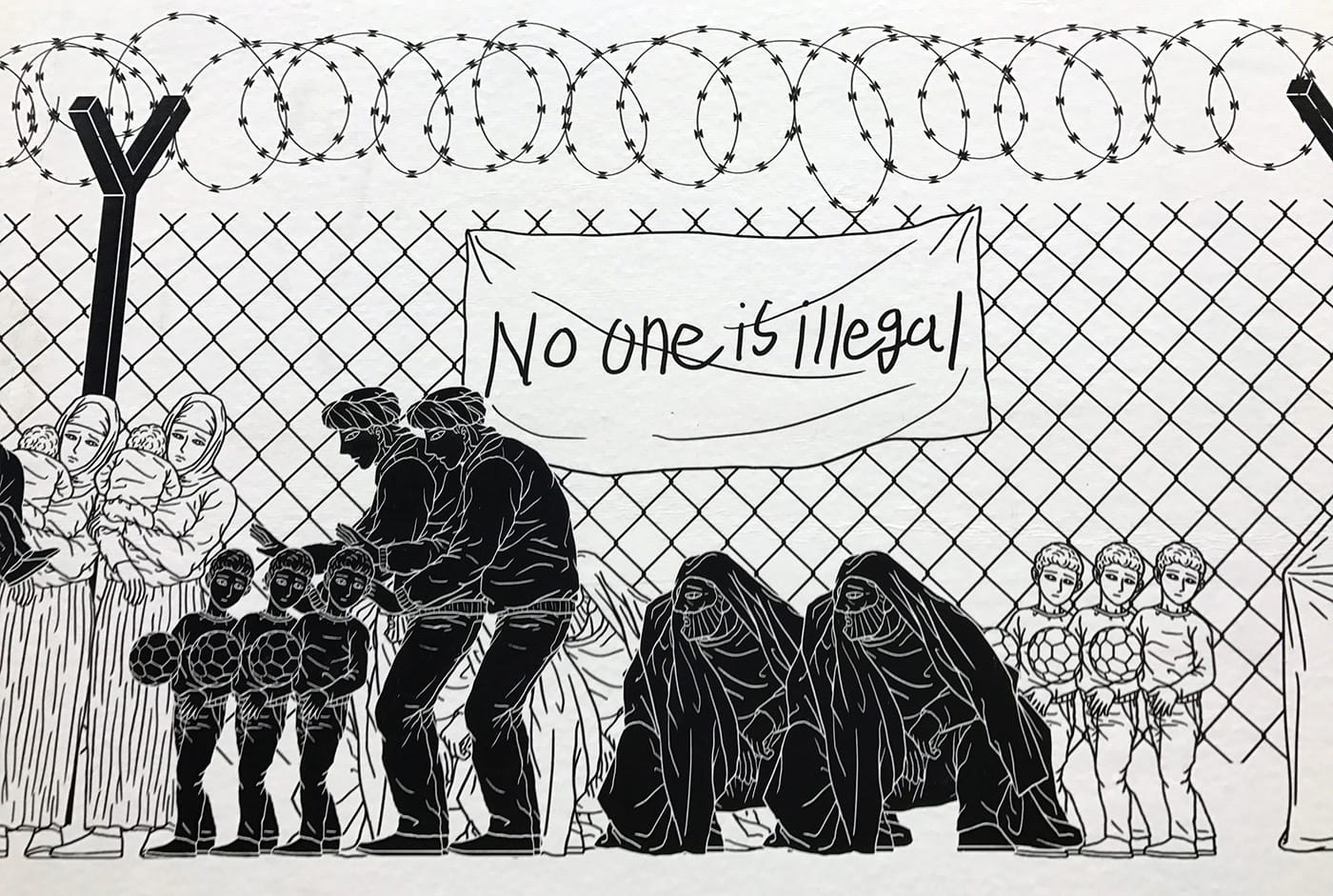

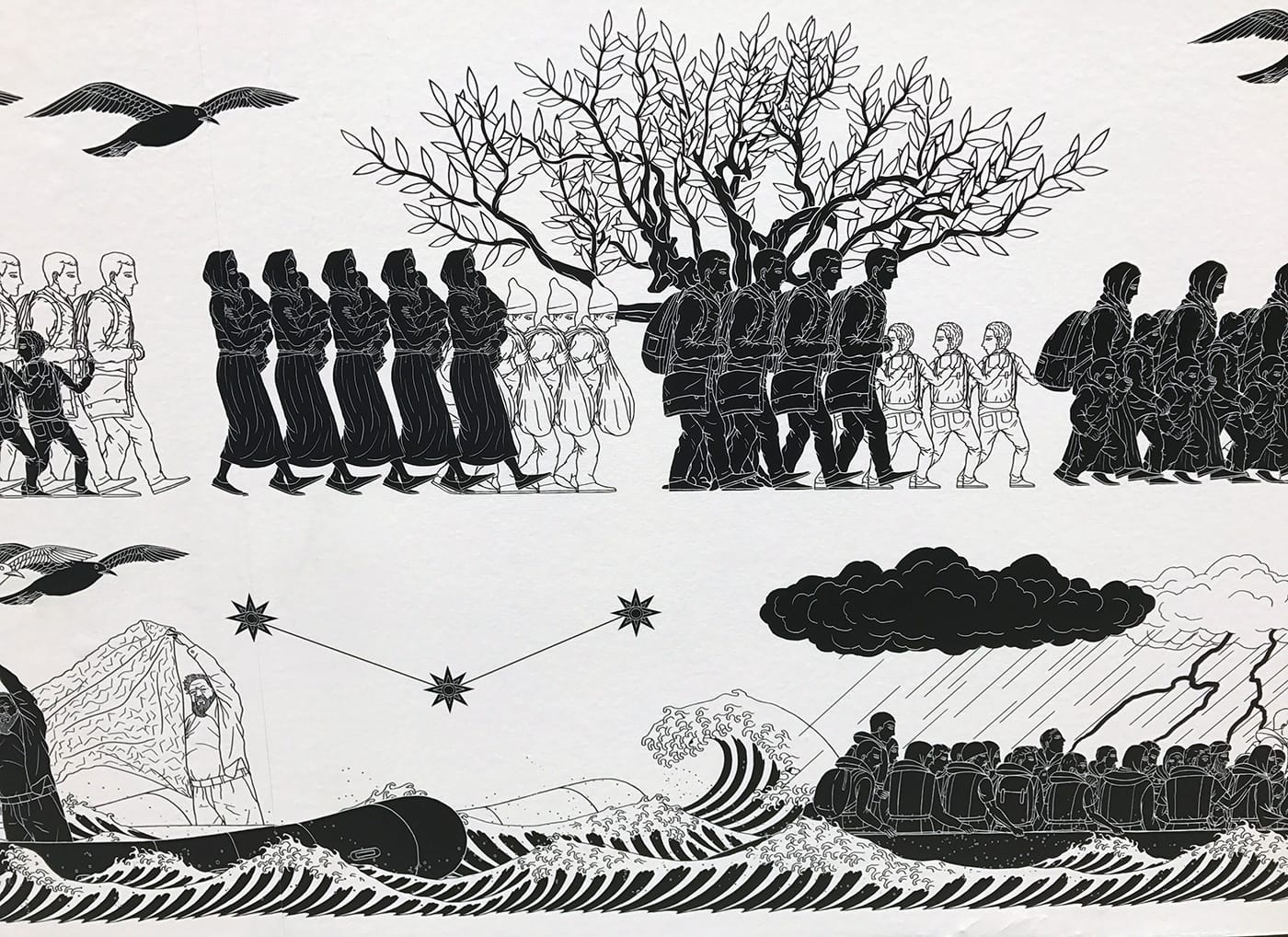

Every gallery is plastered with its own unique wallpaper, but the black-and-white frieze-like backdrop at Lisson Gallery in Chelsea is undoubtedly the best one. The drawing is done in the manner of ancient Greek pottery, but morphed to represent 21st-century political realities of militarization, migration, and escape. Refugee boats navigate waters swelling with images of Hokusai’s Great Wave, which is poised to consume the fleeing masses, who are exposed to the elements and to the whims of nature. But the more threatening imagery pictures militarized forces that shoot into crowds, shoulder RPGs, and ride armored vehicles in an endless march. Tent settlements, presumably refugee camps, are cordoned off with barbed wire and the carcasses of demolished buildings in war zones — notably reminiscent of contemporary battles and scenes in Aleppo, northern Iraq, and the Kurdish regions of southeast Turkey. The patterns, like the violence, seem to go on forever, accumulations of horror with no end in sight.

I asked Ai Weiwei about the current US presidential election and what it’s like for him to be here during such a tumultuous election season. He replied:

No, not really impacting me. What you can see is the world is changing, and changing to all directions. It’s not something you … it’s almost unpredictable. It could be for better or for worse, but people just have to accept it — because even [though] it’s a democratic society, I don’t know how many people [are] involved with the process. If you’re not involved with [the] process, you take the consequences.

Ai Weiwei: Laundromat at Deitch Projects

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches at Mary Boone Gallery, Chelsea

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches at Mary Boone Gallery, Midtown

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches at Lisson Gallery

Ai Weiwei: Laundromat continues at Jeffrey Deitch (18 Wooster Street, Soho, Manhattan) until December 23.

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches (part 1 and part 2) continues at Mary Boone Galleries (541 W 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan, and 745 Fifth Avenue, Midtown, Manhattan) until December 23.

Ai Weiwei 2016: Roots and Branches continues at Lisson Gallery (504 W 24th Street, Chelsea, Manhattan) until December 23.