Ayoung Kim Is Stargazing in a Digital World

Her exhibition at MoMA PS1 synthesizes live-action footage, video game engines, and generative AI to create an interlocking series of speculative narratives

While many prominent Korean artists keep their studios abroad, Ayoung Kim remains rooted in Seoul’s Nakwon Sangga — a once futuristic, now historic commercial complex. From here, she reimagines a city negotiating between the force of capitalism and the persistence of its past.

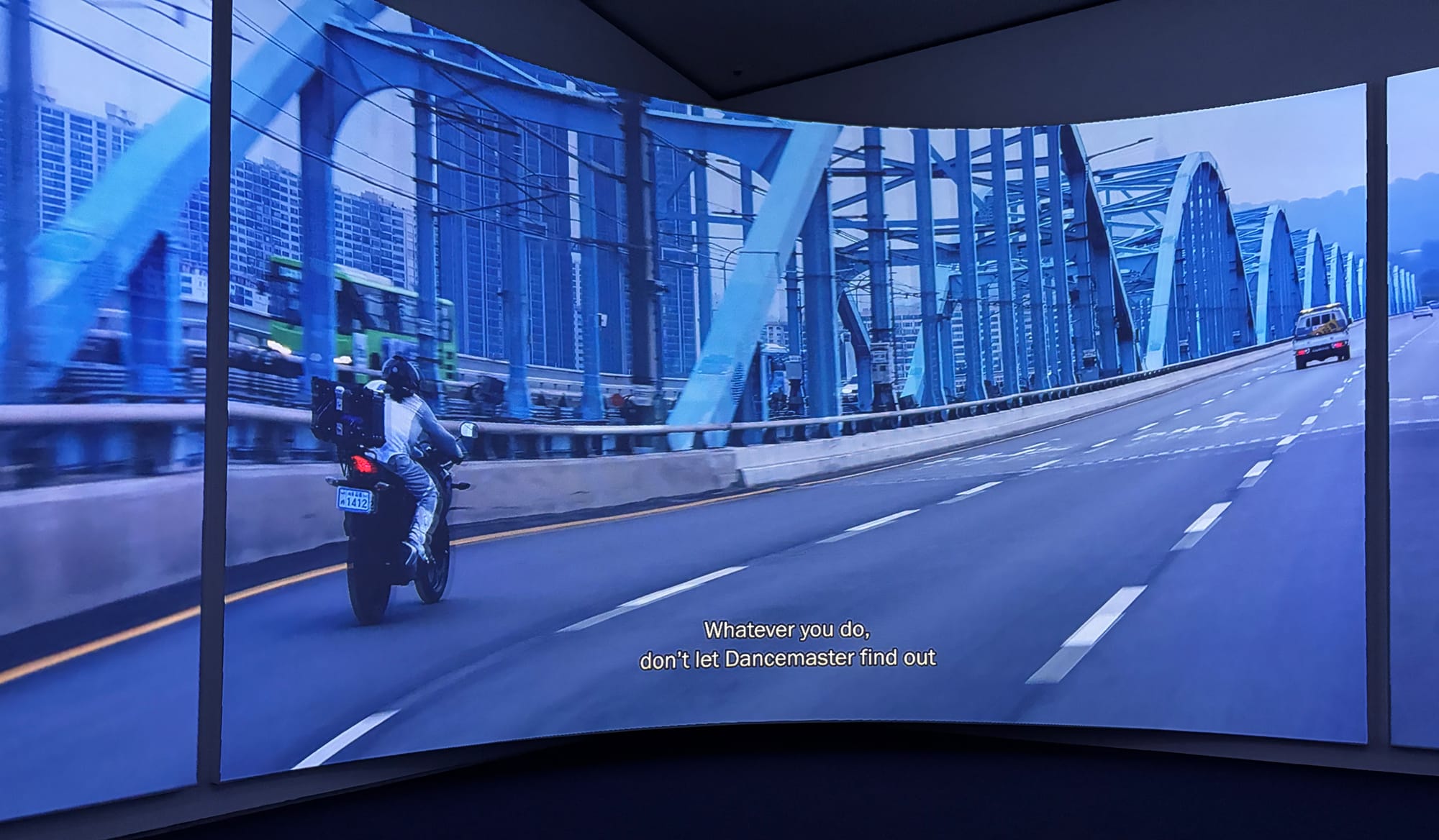

Spread across the third-floor galleries at MoMA PS1, the video installations in Ayoung Kim: Delivery Dancer Codex synthesize live-action footage, video game engines, and generative AI to create an interlocking series of speculative narratives centered on two female drivers, En Storm and Ernst Mo. “Delivery Dancer’s Sphere” (2022), the first in the trilogy, presents a gamified delivery system in which a “Dancemaster” distributes assignments, directing drivers throughout the city. Its demand for optimization compels the drivers to bend space and time, eventually rendering them invisible as they reach the highest level, that of the “Ghost Dancer.” Storm and Mo’s individuality — undermined by their identical physicality, performed by a single actress — suggests capitalism’s homogenizing effects, in which workers are indistinguishable and interchangeable. Their relationship, too, remains ambiguous; it is unclear whether they are lovers or enemies, or even a hallucination of each other. Their physical proximity triggers alarms in the system, from delivery delays that result in lowered ratings to GPS glitches that disable location tracking. While drawing attention to the unnoticed labor that sustains capitalist economies, the work recasts invisibility as a mode of fugitivity — resisting capture as a pin on a GPS system, continuously recalculated for optimal route.

Across the hall, the next two parts — “Delivery Dancer's Arc: Inverse” and "Delivery Dancer’s Arc: 0º Receiver" (both 2024) — expand the prequel’s question of invisibility and fugitivity. In the latter, Storm and Mo race across open desert — initially materialized only as a trail of dust, before emerging in full form across a three-channel screen that spans two walls. In this universe, Storm and Mo fight the Timekeepers’ imposition of the “absolute time,” which aims to foreclose any divergence from standardized existence. A ghostly voice hums a song whose title — “Song of the Sky Pacers” — and lyrics borrow from an ancient Chinese poem used for celestial navigation. Together, the voiceover and the score suggest temporal measurements closely aligned with nature: the awakening of frogs, the Eastern wind thawing frozen soil, among others. Meanwhile, Mo and Storm’s bodies interlock and untangle across three channels, oscillating between acts of tenderness and aggression — an embrace, for instance, quickly gives way to strangling. The indeterminacy of their relationship mirrors divergent temporalities, all of which resist capitalism’s demand for standardization and optimization.

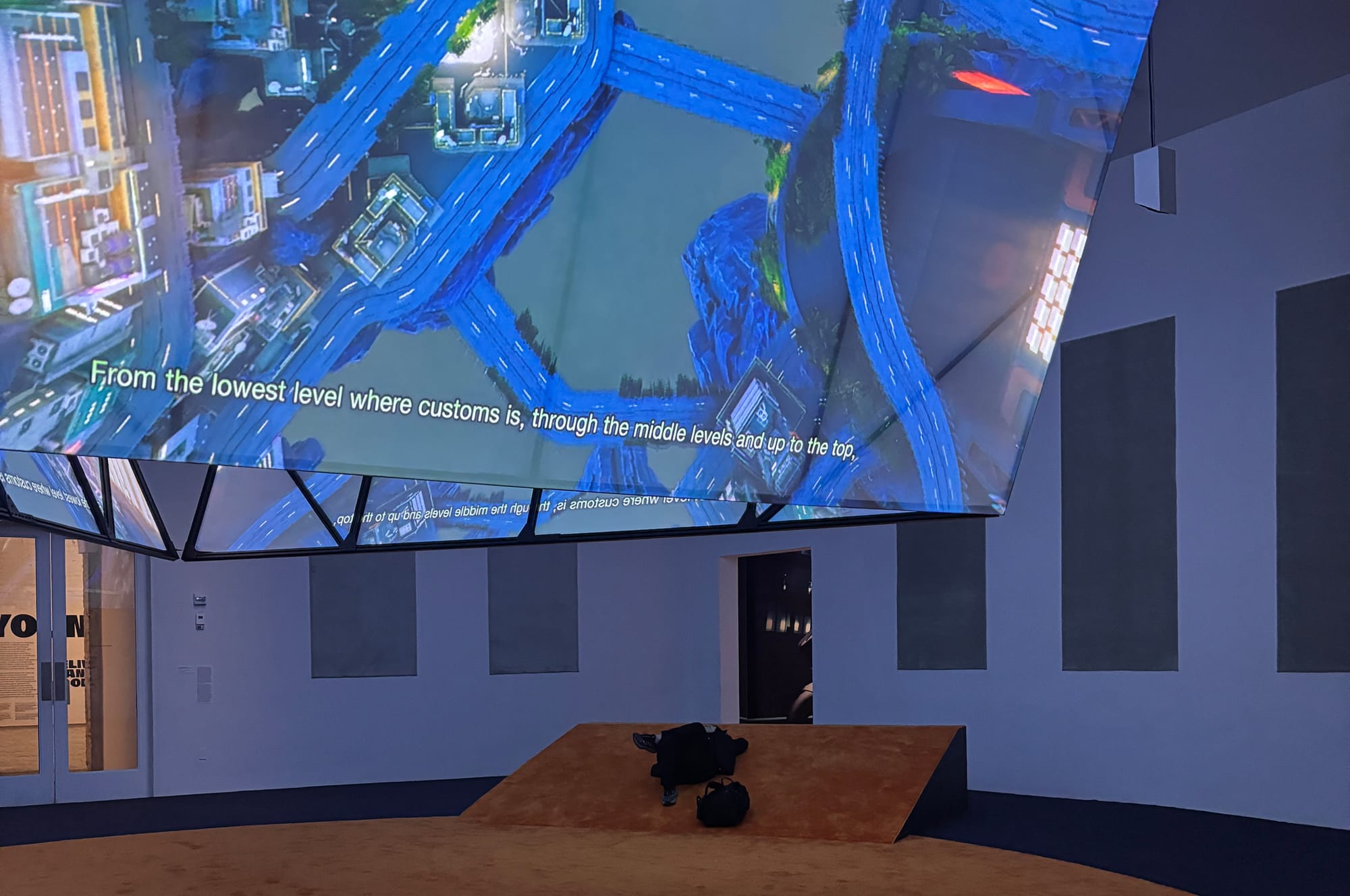

In “Inverse,” Kim introduces a vertically organized fictional world called Novaria, where deliveries move in a single direction, from underworld to upperworld. In an interview, the artist notes how the direction of the human gaze, which was once oriented upward toward the stars as a source of navigation and wonder, now seems fixed downward toward the screen. Unfolding across three large screens suspended from the ceiling, “Inverse” prompts its viewers to look up. Three orange-carpeted slopes run parallel to the screens; seated or reclined, viewers assume the posture of stargazing — only to find the sky fractured across three screens, even displaying different videos at times. Throughout, Storm and Mo appear in multiple stylistic formations from cartoonish renderings that harken back to 1990s animation to game-like universes with raining donuts. If “0º Receiver” refutes imposed singularity, “Inverse” imagines a world where multiplicity might coexist — dispersed across folds and fissures of virtual existence.

The installations across PS1 refuse to position these universes — virtual and proliferating — as secondary or subordinate to the physical; instead, they prompt the viewers to consider these interstices as space in themselves. In fact, the fragmentary architecture of the museum’s repurposed public school building sometimes renders physical installations — from helmets and sundials to prominent use of mirrors — secondary to the virtual landscapes. Displaced from the video installations that feature and contextualize them, these objects, too, occupy a space between marginalization and strategic illegibility.

It is precisely through such fracture that Kim’s universes evade standardization — of time, labor, identity, and desire. Throughout the trilogy, Kim references both modern and traditional methods of spatiotemporal navigation to reframe fragmentation as possibility rather than problem. Drawing on genres ranging from the sci-fi TV series Æon Flux to GL (Girls’ Love) anime, Kim foregrounds how technology carves out spaces for splintered desires. Even as the trilogy interrogates technology’s grip on body and psyche, it mobilizes those very tools to sustain fragmented modes of being.

Ayoung Kim: Delivery Dancer Codex continues at MoMA PS1 (22–25 Jackson Avenue, Long Island City, Queens) through March 16. The exhibition is curated by Ruba Katrib.